A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy by Nathan Thrall. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2023.

Credit:

Ihab Jadallah

One Man’s Tragedy, Dissected, Exposes the Brutalities of Israel’s Rule over Palestinians

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama is set against the backdrop of the tragic 2012 accident involving a bus full of kindergarteners on a school trip from ‘Anata to Kufr ‘Aqab and Abed Salama’s frenzied attempts over the course of the day to learn the fate of his son, who was on the bus. But the story, told matter-of-factly by Nathan Thrall, deconstructs the settler-colonial vise that Palestinians contend with today.

On the face of it, the storyline is fairly straightforward and could be told in a magazine article: A collision between an 18-wheeler and a school bus of kindergartners on a steep, winding road during heavy rainfall claims the lives of six Palestinian children and their teacher; the response to the accident is woefully inadequate; and families come to terms with their losses in various ways. But Thrall, a journalist and former director of the International Crisis Group’s Arab-Israeli Project, delves into the backstories of almost every person who directly or indirectly played a role in the tragic accident or its aftermath. This enables him to pack layers of history and lived experience into the text, all of which is necessary to give the reader the wider political and historical context of the Palestinian Jerusalemites who are the focus of the book.

Through the book’s characters, Thrall introduces readers to the lives of Palestinians who were ethnically cleansed from Palestine in 1948; of Palestinians who remained as unwanted citizens in the new state; of Palestinians who worked in some capacity with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Tunis and returned when the Oslo Accords were signed; of Palestinians who came of age during Israel’s 1967 military occupation and lived through the First and Second Intifada and Israeli prisons; and of Palestinian Jerusalemites contending with the Separation Wall and the many checkpoints that control their mobility (see The Separation Wall and Closure). There are no saints in this book, just people trying to live as well as possible under the dystopian constraints imposed on them.

Some of the Israeli Jewish characters whose backstories we learn include a Jewish immigrant from Morocco whose oppression by western Israelis leads him to join the Black Panthers; a settler residing in a settlement established on the village lands of ‘Anata and who tries to maintain cordial relations with the people he’s exploited; and Dany Tirza, the architect of the Separation Wall, who lived in a West Bank settlement and who “spoke directly to the Palestinian farmers and land owners whose towns and livelihoods the project would destroy.”1

The Bus Accident and the Vise of Israeli Settler Colonization

The bus accident is a tragedy for the Palestinian families and their communities we meet through Thrall’s narration. But the book’s subtitle, Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy, indicates that it is a tragedy for Jerusalem, too. Throughout the book, the author shows exactly why that is the case.

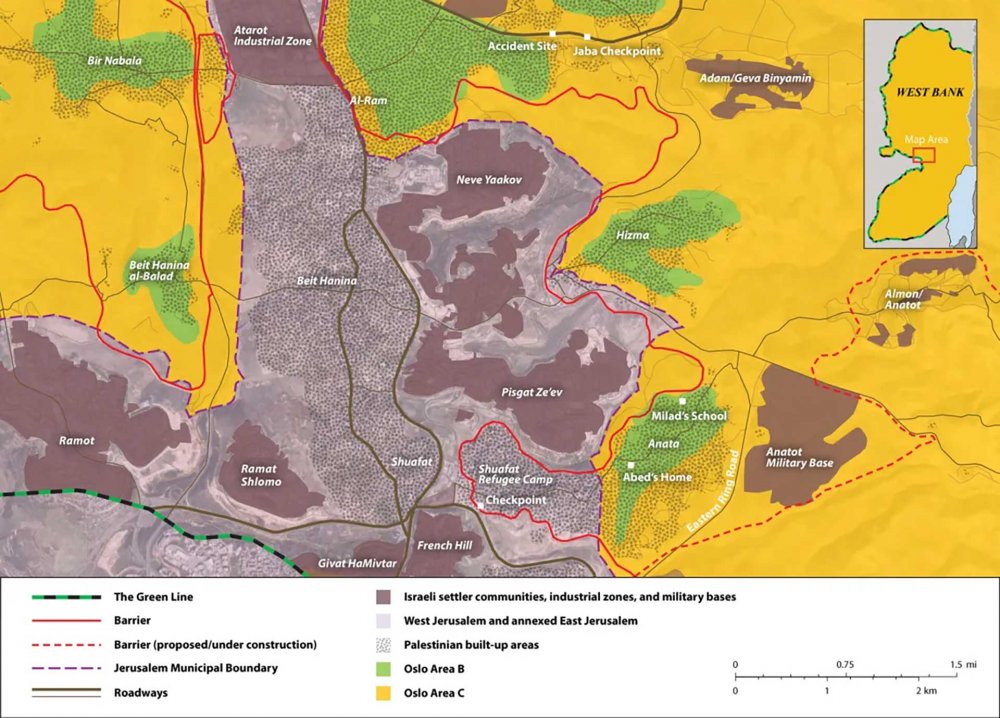

The Salamas live in ‘Anata, a Palestinian town in the Jerusalem governorate that is encircled by the Separation Wall. This heavy statement requires unpacking. Thrall describes ‘Anata as a place of violent takeover: three Jewish settlements have been set up on its lands, and the Salama family lost land to the Anatot settlement and a military base. The Jewish-only E1 housing units and an industrial zone are also nearby.

Abed Salama has a Palestinian Authority (PA) (green) identification card. After the PA was established in 1994, it issued green identification cards for Palestinians residing in areas under its jurisdiction in the West Bank (excluding Israeli-controlled East Jerusalem). Under Israeli military law, because the occupied West Bank (excluding Jerusalem) is a “closed area,” since 1991, Palestinians living there have been required to obtain permits to enter Jerusalem or any other part of Palestine Israel occupied in 1948. Color-coded identification cards determine Palestinian mobility; this detail becomes relevant when Salama learns of the bus accident and frantically tries to locate his 5-year-old son, Milad. Because he lacks the “right” papers, Salama is not allowed to cross the checkpoint to access some hospitals in his search for Milad, so he has to rely on others who can pass the checkpoint to search for him.

That is evident in the book when Thrall narrates his wife’s experience giving birth. When conveying an injured Palestinian or a woman in labor from an area beyond the Separation Wall to a hospital within the wall perimeter, ambulances get ensnared in the mobility regime as well. The (Palestinian) ambulance, which is only allowed to drive in the PA areas, can take the patient as far as a checkpoint on one side, at which point the patient has to get up and cross over by foot to a waiting (Israeli yellow-plated) ambulance on the other side. Sometimes the checkpoint is closed, and people have to drive around to find one that is open, which is in fact what happened to Haifa, Salama’s wife, when she went into labor. She had to walk over to the other side, after Salama bribed the Israeli occupation soldiers with cigarettes, and find transportation. Salama could not pass through the checkpoint with her because he had forgotten his ID at home, and by the time he picked it up and made it to the hospital, he had missed the birth of his child.

The reader of this harrowing story can’t help but understand that this kind of arrangement is conceived of and implemented by colonizers who have no regard for the colonized natives—colonizers who have the privilege of living as though they would never have to endure such unnatural arrangements themselves.

But what does the Separation Wall and Israel’s geographical division of Palestinian land have to do with the accident that claimed the life of Milad, five other children, and a teacher? Quite a bit, in fact. We begin with getting to ‘Anata and picking up the children from the school:

During the Second Intifada, Israel had closed the main entrance to Jaba, blocking it with bounds of earth that had since become a permanent barrier. To get to Anata, Radwan [the bus driver] . . . first had to drive in the wrong direction, into a-Ram, then double back toward the checkpoint on the Jaba road.2

Radwan picks up the children and heads for a play area in Kufr ‘Aqab, and soon after passing the checkpoint, the bus is hit by a semitrailer and rolls over; Radwan is left unconscious. This takes place on a road in Area C, which is under full Israeli administrative and military control. Yet no Israeli sounds the alarm or rushes to the scene. Instead, Palestinians who happen to be nearby see the smoke and rush to the scene to evacuate some of the children from the burning bus. They take the injured to area hospitals in their private cars, since ambulances are nowhere to be found.

Where were the Israelis when the bus was blazing? Salama later wondered how the bus could have burned for more than half an hour, “Yet the soldiers at the checkpoint, the troops at Rama base, the fire trucks at the settlements nearby, they had all done nothing.”3

But that isn’t quite accurate. Israeli ambulances from Jerusalem had been delayed by the army, waiting for it to open a gate in the Separation Wall. Israeli emergency services coming from West Bank settlements or through the Hizma checkpoint in north Jerusalem had also been delayed because dispatchers sent them to the wrong place. Israelis don’t know (or perhaps can’t be expected to know) Palestinian roads and village names, so they use the names of the nearest Israeli settlement for orientation—a practice of no use at all when an ambulance is urgently required at a precise location. Israeli services were minutes away and should have been able to respond quickly, but they did not; Palestinian services require coordination with Israel, which takes time, emergency be damned.

It is not lost on Palestinians that had stone-throwers been on the road, the army would have swarmed the place in no time; and that had Jews been injured, they would have been evacuated by helicopter.

A Palestinian paramedic who arrived on the scene 10 minutes after the crash had to make a quick assessment about where to take the injured. His calculus had little to do with the injuries and everything to do with where he is allowed to drive relatively unencumbered. He decided that his best option was to head for Ramallah. Going to Jerusalem, they could waste valuable time at checkpoints while waiting for permission and then transfer patients to an Israeli ambulance on the other side.

The different legal statuses of Palestinians are meaningless in a crisis; the only thing that matters is whether the patient is a Palestinian or a Jew. “He could never, under any circumstances, bring someone Jewish to a Palestinian hospital,” Thrall tells us.4

And now the torment begins for the parents. Word gets out that there has been an accident, but no one knows for sure what happened or where the children are. Parents start searching frantically for their children. And again, the color-coded identification cards determine where parents can go in their search: Green cards are barred from entering Jerusalem without permits, which take weeks or months to obtain, if at all. At some point, the Israelis magnanimously agree to let some of the parents with green cards cross a checkpoint to search for their children in Jerusalem hospitals.

The dead are finally identified and buried. Who should be held responsible for seven dead Palestinians? The police investigation focused narrowly on the driver; the PA’s investigation was rejected by the families as a cover up for its own inadequate response. A fuller reckoning is provided by the author; it is significant that this occurs in the last two paragraphs of the book. They are worth quoting in full:

For all the blame that was cast, no one—not the investigators, not the lawyers, not the judges—named the true origins of the calamity. No one named the chronic lack of classrooms in East Jerusalem, a shortage that led parents to send their children to [a] poorly supervised West Bank school. No one pointed to the separation wall and the permit system that forced a kindergarten class to take a long, dangerous detour to the edge of Ramallah rather than driving to the playgrounds of Pisgat Ze’ev, a stone throw away.

There was no suggestion that Israel’s fund for accident victims should compensate the families of green ID holders, whose children were killed on a road controlled by Israel and patrolled by its police. No one argued that a single, badly maintained artery was insufficient for the north-south transit of Palestinians in the greater Jerusalem-Ramallah area, or objected that the checkpoints were used to stem Palestinian movement and ease settler traffic at rush hour. No one noted that the absence of emergency services on one side of the separation wall was bound to lead to tragedy. No one said that the Palestinians in the area were neglected because the Jewish state aimed to reduce their presence in greater Jerusalem, the place most coveted by Israel. For these acts, no one was held to account.5

By focusing on a tragic road accident, Nathan Thrall illustrates how real people with specific life trajectories, complexities, and flaws cope with what is arguably the most difficult event that parents and communities can face: the death of children, and particularly the avoidable death of children. Reading this book while Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza is ongoing, it is hard not to see the events it relates as a mere variation, albeit on a smaller scale, on what is underway 77 kilometers south of Jerusalem.

This is the face of Israeli settler colonialism, made glaringly and powerfully visible in A Day in the Life of Abed Salama.