Introduction

Credit:

Martin Nangle, Alamy Stock Photo

Voices of Jerusalem

Snapshot

What does Jerusalem mean to Palestinians who identify as Jerusalemites? We posed this question to more than a dozen Jerusalemites worldwide. We encountered them at random, with no preconditions or particular qualifications beyond identifying as Jerusalemites. Their stories weave a vibrant tapestry of themes that help convey Palestinian experience in, and attachment to, the city. Some took pride in tracing their family history back for centuries, while others grew up in the diaspora and know the city only through occasional visits. All, however, feel a deep identification with the city. Palestinians describe life in Jerusalem through anecdotes of their family history, beginning in the Mandate period and continuing through the cataclysmic upheaval of the wars of 1948 and 1967 and the tightening of the Israeli grip on the city in the 2000s. They reveal the often extreme lengths they are willing to go to today to have their rights as Jerusalemites preserved under the exigencies of Israeli rule, which sometimes means moving further away from the Old City neighborhoods that shaped their identity in order to remain somewhere that authorities will deem acceptable when requiring them to prove that their “center of life” remains within the Israeli municipal boundaries.

Jerusalem has long inspired uniquely strong attachments among Palestinians. As a growing cosmopolitan city in the early 20th century, Jerusalem was becoming a magnetic regional hub, drawing in residents, workers, and admirers from the many villages surrounding the vibrant city.

This was upended in 1948, when Israel was established. During the months before and after Israel’s establishment, what became known as West Jerusalem was virtually emptied of Palestinians, as were dozens of surrounding Palestinian villages.1 Tens of thousands of Jerusalemite city dwellers and residents of surrounding villages were either forced to flee or fled to escape combat zones and became refugees; some settled in what would become known as East Jerusalem and others went farther away, to neighboring countries like Lebanon and Jordan, the wider Middle East, and even North and South America. They were never allowed to return.2

Another mass upheaval occurred a mere 19 years later, when Israel occupied the rest of the city during the 1967 War and then moved rapidly to cut off those who had fled from easily returning to their city, if ever. In both cases, the severance from Jerusalem was abrupt, nonvoluntary, and traumatic.

We set out to explore how Palestinian Jerusalemites in historic Palestine and abroad reflect on their identity and their relation to the city and the trauma their family members experienced when they were displaced during the wars of 1948 (the Nakba, or Catastrophe) and 1967 (the Naksa, or Setback).

In September and October 2020, the Jerusalem Story Team interviewed Palestinians who self-identify as Jerusalemites and found that the memories and attachments remain strongly rooted, even for generations that grew up in other countries later. (Some of the interviewees have asked that their real names not be used.)

Origins

Some of the interviewees’ Jerusalem families trace their origin to the Crusades era (roughly the 12th and 13th centuries), while others identify a connection to the first and second Islamic conquests of the seventh century (see Community Profile). Sociologist, author, and parliamentarian3 Bernard Sabella, 78, taught at Bethlehem University for 25 years until he retired; he currently lives with his family in their home in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Beit Hanina. He maintains that the Sabella family name suggests an association with the Crusades. His sense of his family’s Palestinianness is rock solid: “We are unequivocally Palestinian.”4

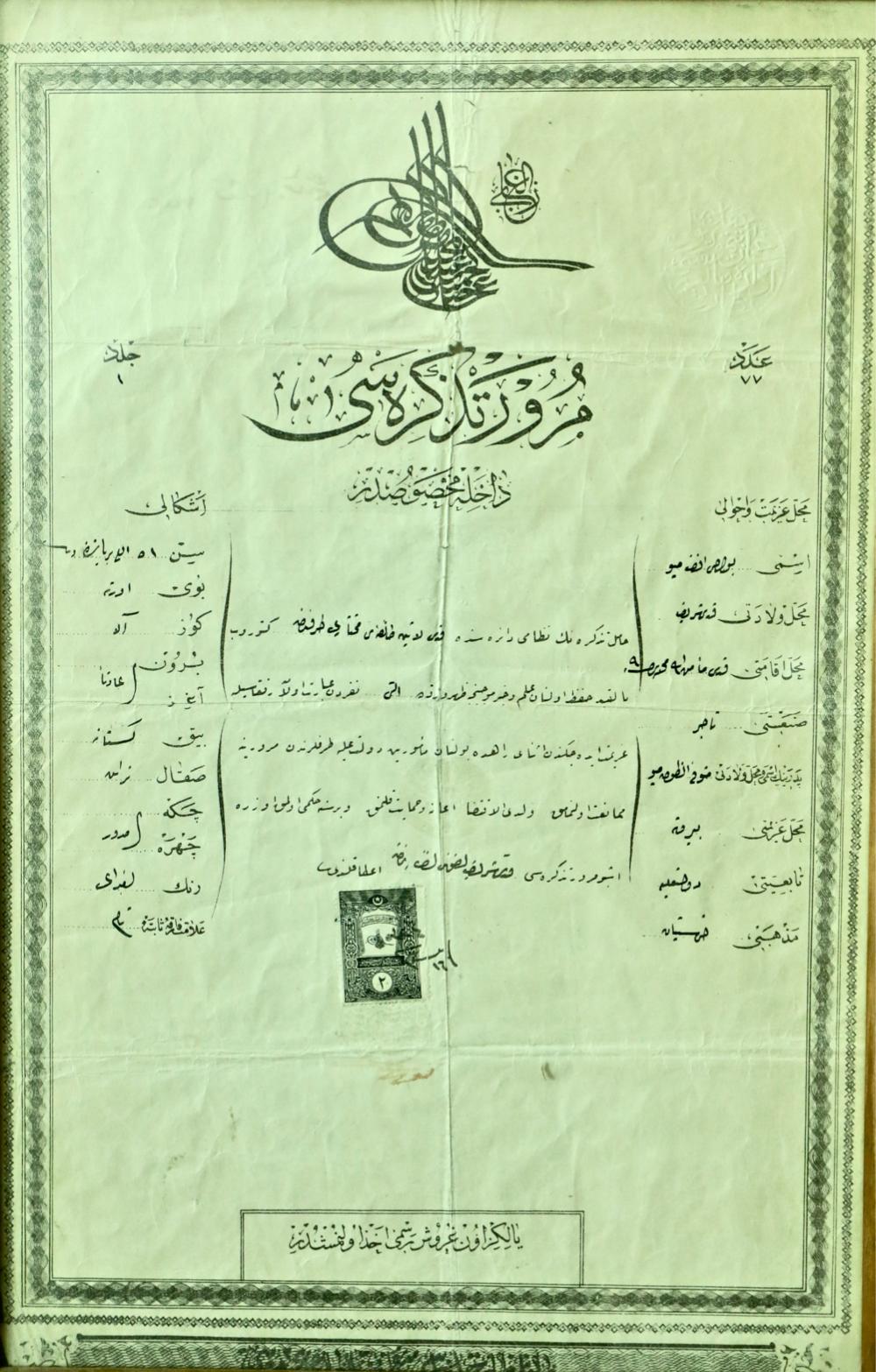

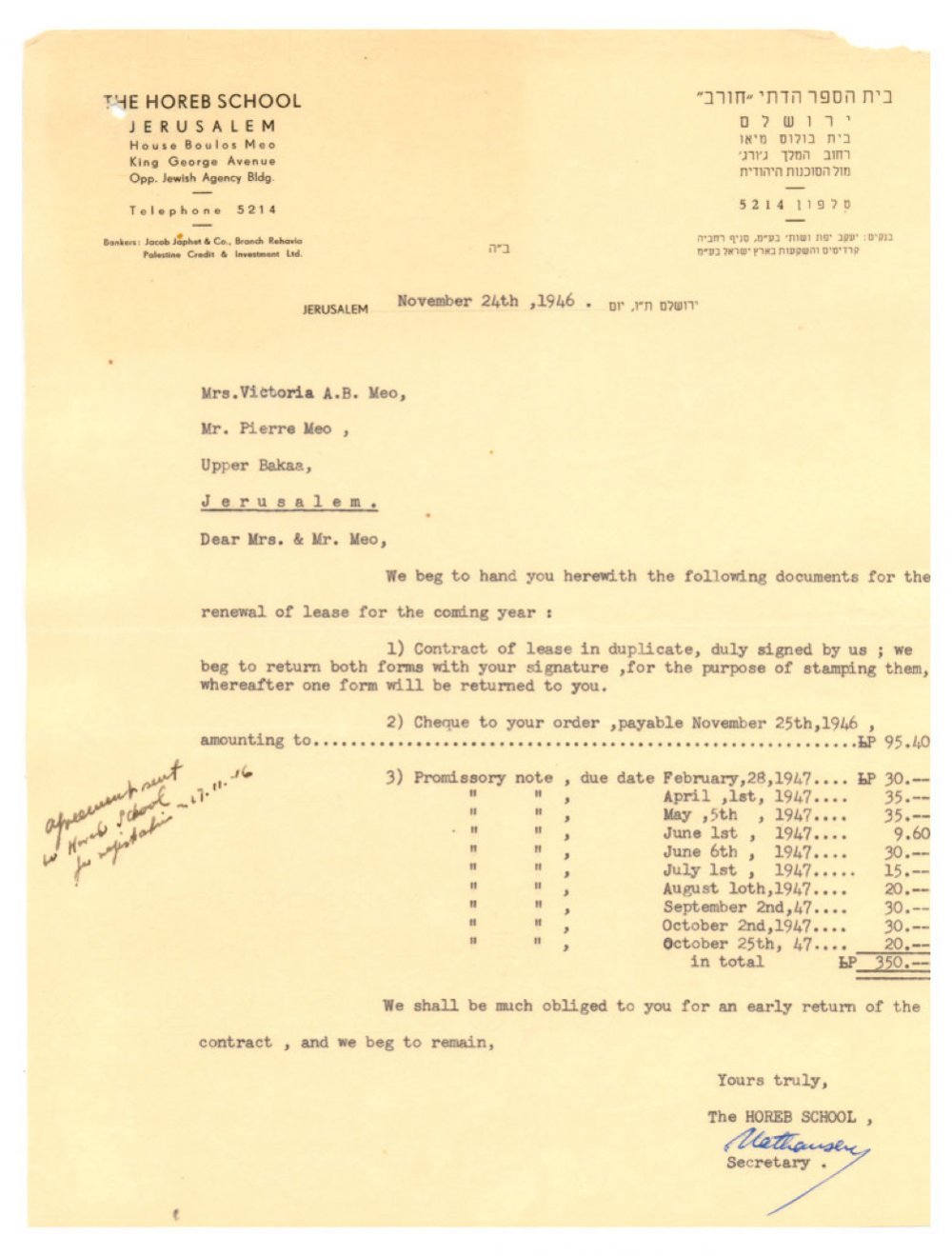

Sani Meo, 60, is co-owner and publisher of Turbo Design and Jeel Publishing, which publish This Week in Palestine and Filistin Ashabab magazines, respectively; he lives with his family in their home in the Palestinian neighborhood of Beit Hanina in East Jerusalem. Sani is a proud Jerusalemite with an Italian family name. He explains that many families in Jerusalem have surnames that suggest Italian roots, such as Meo (originally Bartolomeo), Alonso, and Lorenzo. Their Italian forefathers made their way to Jerusalem during the Crusades era. “I am a Jerusalemite as my father and my grandfather were before me.” He has lived in Jerusalem his entire life, despite the fact that his business (founded in 1985) is located in Ramallah and he has had to brave the Qalandiya checkpoint ever since it was first established. Like many others who lived in or were born to parents who lived in Jerusalem before 1948, Sani is “a mixture of the East and the West.” He explains that his mother’s family were culturally more eastern; his uncles had Muslim names, like Ali and Hosni. His uncles on his father’s side have French names, which he attributes to the influence of French culture on their Lebanese mother.

Some Muslim families—the Husseinis, the Khalidis, the Nusseibehs, and others—arrived in Jerusalem with the first Islamic conquest in the seventh century; others came in the 12th century after the second Islamic conquest by Salah al-Din.

Some of these families trace their origin to Morocco. Soon after the conquest of Jerusalem in 1192, the Moroccan neighborhood (later called Haret al-Maghariba) was established to accommodate Moroccan immigrants. Fatima Moghrabi, 25, an accountant who lives in Kufr ‘Aqab on the “other” side of the Separation Wall, says that both her paternal grandparents are originally from Morocco.

My grandmother is from Morocco and she’s been living here for a long time, we don’t actually know since when . . . She was originally from Casablanca. My grandfather is the first generation of his family to be born In Palestine. His father came from Morocco and got married here and his children were the first generation, and we are the third generation. My grandfather was a school principal in al-Thuri, and my grandmother was a homemaker.

Moien Odeh, 39, a human rights lawyer who grew up in Silwan in Jerusalem and is now a PhD candidate at George Mason University’s Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution in Washington, DC, is less interested in his family’s origins; his roots are represented by his family home in Silwan, where his parents and grandfather lived: “My grandfather is from Silwan, and my great-grandfather is from Silwan, and this is all I need to know.” For Moien, his connection to the city has been solidified over generations of continuous residence.

Life in Jerusalem before 1948

Before 1948, Jerusalem was a cosmopolitan city. The city was home to people from different parts of the world and different cultures and religions; it allowed them a space to meet and create a life together. It was also a business center, an economic hub, and a magnet for the interest in the city on the part of internationals, particularly pilgrims, that took off starting in 1839 with the Ottoman Empire’s Tanzimat reforms and grew rapidly during the second half of the 19th century. For families like the Meos, this rise in tourism and pilgrimages provided opportunity. Thus, in 1872, Sani Meo’s great-grandfather, Boulos, decided to open a shop by Jaffa Gate that would cater to these customers, a shop that would sustain the family fortunes for 124 years. As Sani explains:

They [the family] were merchants; my great-grandfather Boulos was the one who started the family business in 1872, and it stayed with the family until I sold it in 1996, so the business stayed in the family for 124 years. It started as a souvenir shop in the 1800s. Their customers were tourists who used to come via steamships and travel in groups; they used to sell them wood, olives, and seashells, and so on, then the business was developed and started selling antiquities, Persian carpets, lithographs, and metal engravings, and so on, but mainly it was a souvenir shop. So when the Zionists start to talk, we tell them that our family’s business existed 45 years before the Balfour Declaration. So don’t tell us we came from the Arabian Peninsula.

Several families trace their origins to surrounding villages of Jerusalem, while others made a life-changing decision to work and live in Jerusalem to secure for themselves and their families a more prosperous life. Ramy Saliba was born and raised in the United States to two Palestinian immigrants and is now a law student at the University of Michigan. He explains:

After 1920, after World War I and the start of the British Mandate, there were a lot of people moving from the countryside to Jerusalem. I know anecdotally that there was a lot of migration from Hebron at that time. I know Jifna was one of the big cities/towns that had a lot of immigration. I think it’s just one person in the family moves and a lot of people follow. A few families from Jifna lived along an alleyway in Haret al-Sa‘diyya, I think they still live there today. My grandfather’s youngest sister lived there until she passed away a few years ago.

Families who immigrated to Jerusalem, especially from the rural areas during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, lived inside the walled Old City. Some even resided in houses that belonged to the Islamic waqf. Fatima explained that her paternal grandfather’s family lived in property belonging to the Islamic waqf endowment in Haret al-Sharaf (in what is today part of the Jewish Quarter). Such properties are built either for private (family-based) profit or for the public and charitable reasons, providing shelters and homes for people in need such as those who were seeking refuge after the war.5

Families with social standing were able to obtain property outside the Old City. Yara and Yasmeen Alami recount their mother’s family history: “Originally they are from Nablus, but they have lived in Jerusalem for about 150 years,” and due to their social standing, “they lived all their life in Wadi al-Joz.” Yara, 29, has a master’s degree in international relations and works as a public relations manager; her sister, Yasmeen, 27, has a master’s degree in business administration. The sisters identify as Jerusalemites, even though they have lived in Dubai for the past 20 years.

Many people from the rural areas moved to Jerusalem, attracted by its vibrant economic life and the opportunities it offered them to improve their socioeconomic status. In the 1920s and 1930s, residents of the surrounding villages went to metropolitan Jerusalem for work and business and were considered part of its daytime population.6 By 1929, Jerusalem had grown to include the surrounding villages of Lifta, ‘Ayn Karim, al-Maliha, and Deir Yasin, and it contributed to the evolution of social relations and the politics in those localities7 (see The West Side Story). By the end of the first decade of Mandate rule, Jerusalem had been transformed, especially in the localities of the Western Corridor. It attracted and combined a vast array of non-elite populations that greatly affected the social character and demographic feel of the city, and its relationship with the villages in the outskirts of the city had changed.

US-born Dalal Liftawi, an academic, explains that the maternal side of her family were considered the elite of Lifta; the women in the family studied in Jerusalem, and Dalal’s mother’s aunt was the right-hand assistant of Hind al-Husseini, who founded Dar al-Tifl al-Arabi, initially as an orphanage for the children of Palestinians who were killed in the Deir Yasin massacre.8 (It has since become a school and museum.) Dalal draws inspiration from her extended family’s deep and long roots in Jerusalem and the pride they take in Lifta.

The interlink with the Jerusalem fabric of the surrounding localities such as Lifta was also manifested in investments in land and property. Dalal explains: “The area that has been owned by Liftawis goes all the way to Bab al-Khalil. It is really interesting to see the expansiveness of the area of Lifta and to understand how many people have actually been evacuated and how much land was taken around Lifta.”

The 1930s and 1940s in Jerusalem marked a shift in Palestinians’ socioeconomic life. Families who moved to the Old City soon moved west beyond the walled city or to the Sheikh Jarrah or Musrara neighborhoods when they became even slightly more affluent (see The West Side Story).

Ali Malek, a researcher and educator in media studies and the social sciences, was born and raised in the UAE. His grandfather, born in the 1920s (“we don’t know the exact date but I think in 1926, so when the Nakba happened he was 22”), lived in the Musrara neighborhood outside the Old City walls. Ali’s grandfather’s family were working class, and they seemed to experience fluctuations in their disposable income: “Sometimes they were rich, and other days they were poor.”

[My grandfather] used to tell me that when he was a child, his life was better, and it got harder as he grew older. He studied in St. George until the last grade, but he left sometime in the 1940s before he graduated; he was 17 at that time. He was forced to leave school because he had to start working. I know that in the last few years as a student he did not pay his tuition; I am not sure whether he was offered a scholarship or if the teachers loved him so much, they did not make him pay. But I know that St. George’s tuition was expensive, and he reached a point where he was not able to pay. . . . My grandfather told me that his father and grandfather were rich, but when he lived in Jerusalem their financial situation had changed; they sent him to work in Tiberias, but he eventually ended up working with British Airways in their office in King David Hotel in Jerusalem.

With the economic hardship they faced, Ali’s grandfather’s family had to leave Musrara.

Ramy described his grandmother’s family as fellahin who had moved to the city; the grandmother’s working-class parents did not finish elementary school. In Jerusalem, they were able to secure a better life for their children, including education. “My grandmother’s younger brothers had the opportunity to go to college, but they’re the first.”

As their financial situation improved, they moved out of the Old City to the Western Corridor in Mamilla Pool and stayed there until 1948. Others who were not as fortunate stayed in the walled city, like Ramy’s grandfather, who remained with his family in Haret al-Sa‘diyya.

Middle-class and aristocratic Jerusalemites made their home in the Western Corridor. The family of 32-year-old NGO worker Hany Khalidi were among the prominent families living in what is now West Jerusalem. “My great-grandfather, Ahmad Sameh al-Khalidi, was the head of what was called the Arab College, which was one of the most prestigious educational institutes for young men.” The family lived in the school.

Bernard recounts stories of his family in the 1940s. “We were a middle-class family, a little bit of a bourgeois family, but not very rich, but [my father] was paid a good salary during the British Mandate.” This had helped the family to build a house in Qatamon, a middle-class, bourgeois Palestinian neighborhood outside the Old City wall that was entirely and permanently emptied of Palestinians in 1948 (see Recollections of an Old City Childhood in the Shadow of the Nakba).9

My parents and uncles—God rest their souls—they built a small house in Qatamon in 1937. My sister Hilda told me that our house in Qatamon was near a British army barracks and an ice cube factory, which doesn’t exist anymore. In place of the factory, there’s a hospital on part of the land, which I have visited for medical tests.

Born three years before the Nakba, Bernard has little memory of the family house in Qatamon:

I was born in 1945 at the hospital that was behind the current (Israeli) Jerusalem municipality building. . . . What I remember from that house isn’t much, but I remember the yellow bus that used to take my sister Hilda and brother Abdallah to school when I was about three years old. . . . I remember a chicken coop that my aunt Leonie—God rest her soul—used to take care of.

Sani describes a life of luxury in the Western Corridor:

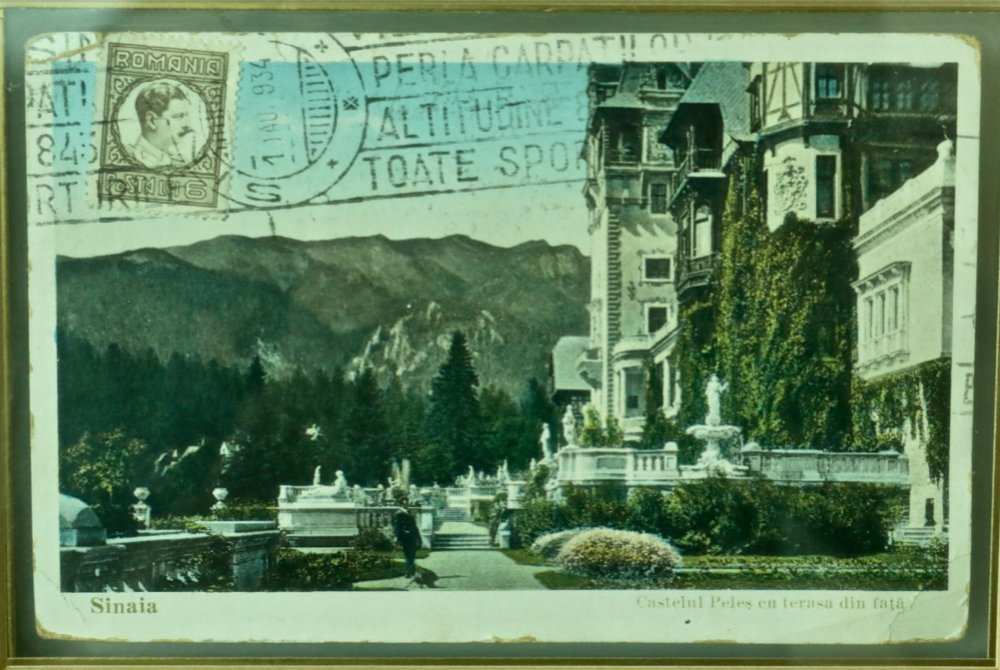

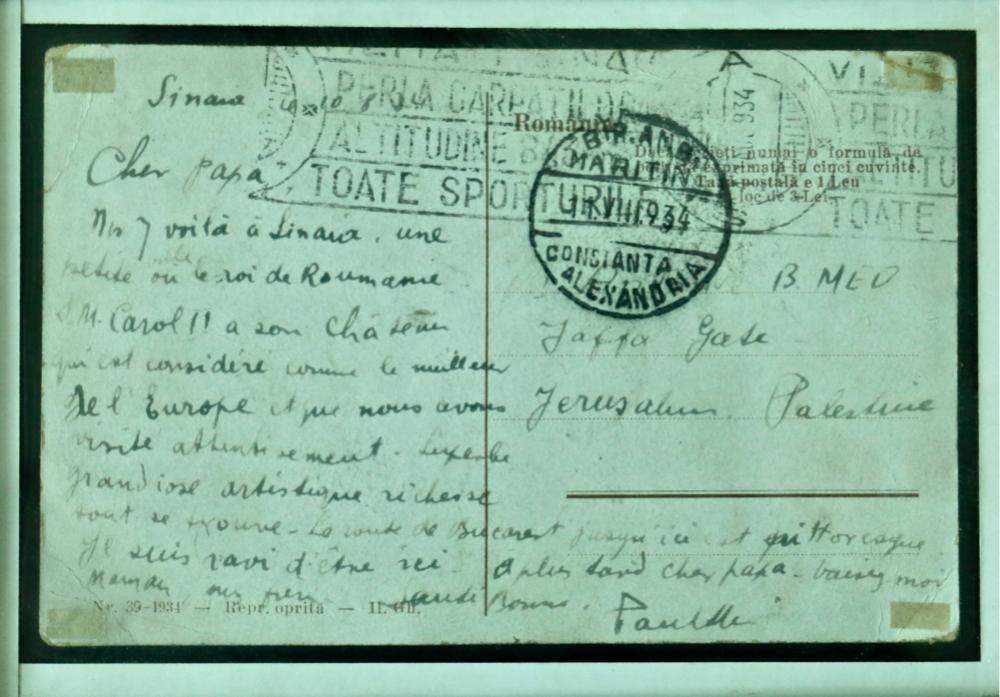

My uncle Roland was Palestine’s tennis champion in the 1920s and 1930s. My father never went to school on foot, always in a car or some other vehicle, a type of protection because they were considered wealthy. In 1948, my grandfather’s house was leased as a school, it was that big. They lived in the King George [Street] area in Jerusalem, and they built another house nearby, which they rented out for 350 Palestinian liras in the 1940s. They lived like aristocrats. We even have postcards written in French that my father sent from Europe in the 1930s and 1940s.

From stories he was told, Sani concluded that in the 1920s and until the 1940s, the lifestyle of wealthy Palestinians in the western neighborhoods was disconnected from the political situation. They enjoyed parties even during periods of political unrest. This disconnect from the political environment was due to the comfort afforded by wealth:

Everything was lost in 1948. Not only the properties [two homes in West Jerusalem and most of their personal property] were lost, but more importantly they were broken by it and lost their spirit. My grandfather had five young men, but they were not resilient enough to handle the Nakba. Their fate was similar to all of those who lived in the Western Corridor in the 1930s and 1940s. They were not very politically involved, while the Zionists were targeting them; eventually they had to leave their houses and lost all their properties.

Due to its location in East Jerusalem, which came under Jordanian rule after the 1948 War, the shop was able to survive. Everything else on the western side of the city was expropriated by Israel.

Life in Jerusalem during and after the Nakba

Many Jerusalemites, especially those in the part of the city that became West Jerusalem, were forcibly displaced from their homes in the 1948 War.10 Many families found refuge in neighboring Arab countries, like Lebanon and Jordan; some managed to return to East Jerusalem and live in the crowded Old City or in refugee camps with the other refugees from Jerusalem and the neighboring villages.

Ramy’s grandmother and her family were forced to leave their house in Mamilla. Initially they found refuge outside of Jerusalem, but they were able to find their way back to the city: “They were lucky; I guess they had a home base in the Old City and were able to return to it.”

Hany explains that his great-grandfather’s decision to leave his home was primarily because they lost their sense of security in their home: “The [Jewish] neighbor whom they’d lived next door to for a few years started shooting at them. There was shooting outside the school. So I think they felt threatened.”

Bernard’s family headed for Lebanon.

I have a faint memory from our journey back from Lebanon, from Ghazir [a suburb of greater Beirut], of the taxi driver, Shimon—a Syriac—who took us to Bethlehem. I think I was about five or six years old. A relative of my dad’s, who had a big room in a hosh [large residential complex], told my dad that we could go stay there. I remember Bethlehem, but especially the place where we lived for about a year. Subsequently, my dad got good news that his old job in the Jerusalem municipality was open to him in the “Jordanian” Jerusalem municipality. And so we moved from Bethlehem to Dar Musa Effendi in the Old City of Jerusalem. Dar Musa Effendi has a special history, it used to belong to Musa Kazim al-Husseini, who was one of the first mayors of Jerusalem.

Most of the families who left Jerusalem after the Nakba, like Hany’s and Ali’s grandfathers, were never allowed to return.11

Dalal describes the forced evacuation of the village of Lifta:

My father’s parents were evacuated. [Zionist militias] would go on the roofs and poke holes in it; when their home ceilings started to crumble, people got scared and left. Those who weren’t frightened by these tactics were frightened when villagers told them what happened to their village and would surely happen to them. So they left. They actually locked up their homes and they left thinking that they would come back. I have the key to my maternal grandparents’ home, which my uncle ended up giving me. It’s like one of those really old keys. And I have it on display in my house.

Many families were unable to return home, Dalal explains:

My mother’s family went to Jordan and my father's family ended up in Ramallah in a refugee camp. And my father was born in the refugee camp. I know in 1967, when the war occurred, my father’s family was actually trying to return to Jerusalem. Then the 1967 War happened, and they all ended up getting dispersed.

Many of those who did try to return back to their homes were killed. Ramy recounts the trauma of leaving behind the home in the Western Corridor, which was manifested in different ways:

I think it was [my grandmother’s] aunt or her relative who after the hostilities calmed down wanted to go back; she went back to her house [in West Jerusalem] that she’d been living in and never came back. Someone later said that they found her shot dead in front of the house. She had said that she wanted to go back because she left her hens. She wanted to go get her things; [when the war happened] she just packed up, you know, it was like [they were] forced out all of a sudden. I think like most 1948 refugees, they didn’t think that they’d be gone forever.

While Bernard and his family were able to stay in Jerusalem, he could not live in the home his family had built. After 1967, he and his siblings went back to the family home in Qatamon (in West Jerusalem) to see what had happened to it. The house had been demolished, and the Israelis were constructing a large building in its place. Bernard and his sister told the Israeli construction manager that the original house had been their home, and the manager informed them that the Israeli government considers them “present absentees,” a legal construct within the body of laws created by Israel to seize the property of Palestinians who were driven from their homes by Zionist Jewish forces before the establishment of the State of Israel (or by Israeli forces after Israel was established) and who remained within the borders of the state. Even today, the state bans these internally displaced persons (IDPs) and their offspring from returning to their homes.12

Bernard describes some of the intangible losses that accompany the loss of a home: “This pain [of the loss] is not just about the land and the house, it is about the conversations we had, the family’s heritage, the soul of the family . . . and the social bonds that we had back then that we feel we have been deprived of.” Bernard’s daughter, Margaret, remembers her father driving the family to their former West Jerusalem neighborhood of Qatamon often to show them where his family used to live and to show them the tree that his uncle had planted.

Community Connections in Times of War and Exile

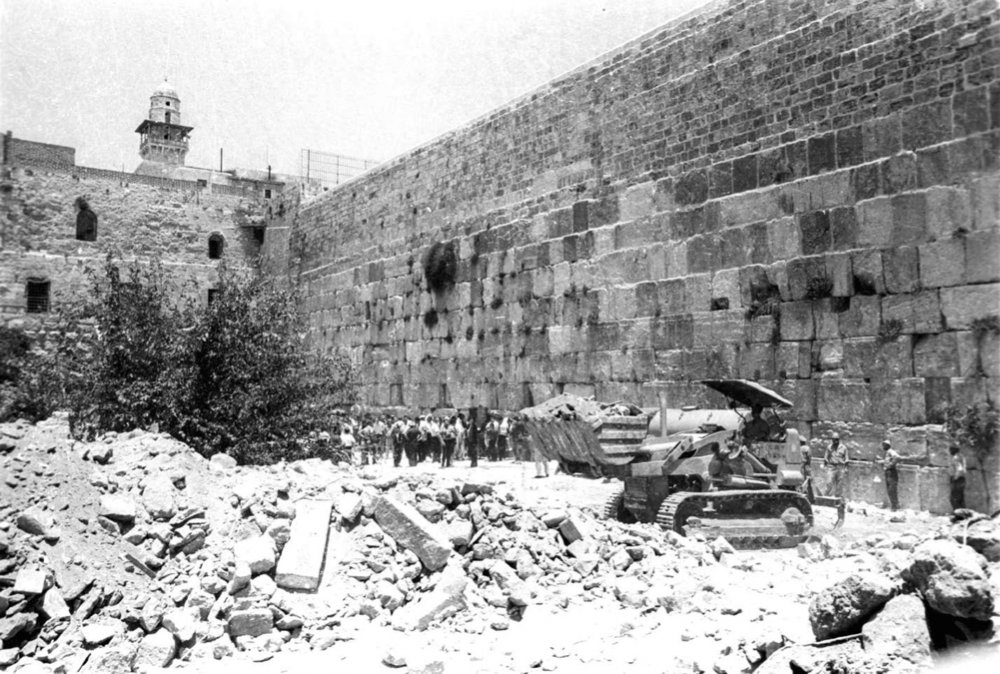

The 1967 War created fresh stories of exile. Fatima’s grandmother was forcibly evacuated from her house in the Moroccan Quarter to another house in the Old City within walking distance of her old neighborhood. It was scarring for her to be placed in a house from which she could witness the demolition of her old neighborhood in order to expand the plaza in front of the Western Wall (see What Is Jerusalem?).13

The destruction of the old neighborhood led to the scattering of Fatima’s grandmother’s family. Some siblings went to Morocco, where the family is originally from, and others went to Iraq. Her grandmother continued to live in the Old City in Haret al-Sharaf (which abuts the area that used to be the Moroccan Quarter) with her husband and children.

Others tracked the changes wrought on their city from afar and with anguish. For Dalal’s paternal family, the 1967 War meant another experience of displacement and tearing of the family fabric:

My father and his sister were separated from their parents and the rest of their family for almost two months until they were able to find each other. They thought that another war was going to happen or something was going to happen. And my father ended up taking his younger sister to Jordan through Allenby Bridge where, you know, under the bridge there's actual water. So, a lot of people used to kind of go through there to cross over to Jordan, there is the river that connected from Palestine to Jordan. And so my father at the age of 18 was carrying his sister on his back, and then his sister kind of almost fell into the water. And there was another guy who went and grabbed her and saved her. And this idea of community—even though they’re under attack, they’re in this world of uncertainty—there’s always communication and a strong bond between Palestinians.

This sense of community in the darkest hour was echoed by many interviewees. After the exile of 1948, Sani’s family found refuge in East Jerusalem in the area of Salah al-Din and Bab al-Zahira, around the district court. Unlike his father, who grew up in a luxurious house in West Jerusalem, Sani grew up in an apartment in Wadi al-Joz, in East Jerusalem, and their neighbors were like family:

We lived in a two-story building. When the invasion began [in 1967] we went down to Fleifel’s family house where we used to play with their kids . . . they were a part of our family. I remember when we bought a TV, they used to come watch a movie with us on Friday when they did not have a TV of their own. We were a family, so we went to their apartment to protect ourselves, and we used to hear the bombs and the gunshots.

For Sani, Bernard, and other Jerusalemites, their identity around Jerusalem was structured and enforced by their surroundings. For many people, reuniting with the scattered community was a way of keeping a sense of normalcy. Bernard explains that often the refugee community would look for those who came from the same place and pitch their tent or rent a room next to them. Bernard recalls:

Our parents’ first priority was to resume life as it had been before 1948, because all the Qatamon families became refugees [in 1948], as well as families from ‘Ayn Karim and Talbiyya and other villages [in West Jerusalem] en route to Bethlehem who were all expelled from their villages [in 1948]. What I remember of our family life in the 1950s is that every year on my father’s birthday, my mother—God rest her soul—would clean the house from top to bottom: curtains, and so on, and the families who had been our neighbors in Qatamon came to celebrate my father’s birthday as a continuation of the tradition from [the time] when they lived there, to maintain the social ties, as many Palestinian families did in the refugee camps.

Living in Jerusalem and being part of the social fabric of the city forged and continues to forge the identity of its people, wherever they are. Yara’s mother has lived in the UAE for many years, but her sense of herself as a Jerusalemite is unshaken. Ali’s grandfather moved to four different countries before residing in Sharjah in the UAE. But for him, Jerusalem is his home: “My grandfather is very proud to be a Jerusalemite. He tells everyone—anyone who asks him where he is from—he tells them, ‘I’m from Jerusalem,’ and today he feels guilt and regret for not returning to Jerusalem.”

Maintaining a Jerusalemite Identity despite Exile

Unlike Sani and Bernard, whose identity stems out of growing up and living in the city, Jerusalemites who left formed a strong cultural, social, and political identity with the distant city. Descendants of these Jerusalemites inherited their identity as Jerusalemites from the stories they heard and from the political education taught by members of their family.

Ali’s connection to Jerusalem was strengthened through his visits to the city. His identity to Jerusalem is cultural, social, and political because both his father and grandfather instilled in him a deep connection to Jerusalem throughout his life. They told him stories and took such obvious pride in being from Jerusalem.

My political identity and awareness of the Palestinian struggle were mostly formed around the Second Intifada after the killing of Muhammad al-Durra.14 My grandfather was the one who taught me about Palestine, as here in schools we did not learn anything [on the subject] so he was always eager to instill in me the idea that I too am a Maqdisi, even if I was born in Dubai and did not live in Jerusalem. At the time of the Second Intifada, I was not even in Jerusalem, I did not even know back then how Jerusalem looks. When Muhammad al-Durra passed away I was six years old, so I held on to my identity that was built in me through my grandfather’s words, without any idea on what is Jerusalem, beyond that Jerusalem is our hometown where we originally are from.

“He was always eager to instill in me the idea that I too am a Maqdisi, even if I was born in Dubai and did not live in Jerusalem.”

Ali

For his grandfather, it was important to make sure that Ali understands that he is a Maqdisi and not only a Palestinian: “All the neighbors around us [in Sharjah] were Gazans, and he [my grandfather] used to insist, that ‘you are different—you are Maqdisi. All of us are Palestinians, but you are Maqdisi.’”

For many Jerusalemites, especially in the diaspora, cultural identification as a Jerusalemite is not organic.

Hany was born in Europe to a Jerusalemite father who was born in Beirut. He regarded his Palestinian and Jerusalemite identity to be political, not cultural, mainly because he does not speak Arabic and because he is aware that Israeli policies are designed to erase the Palestinian connection to the city.

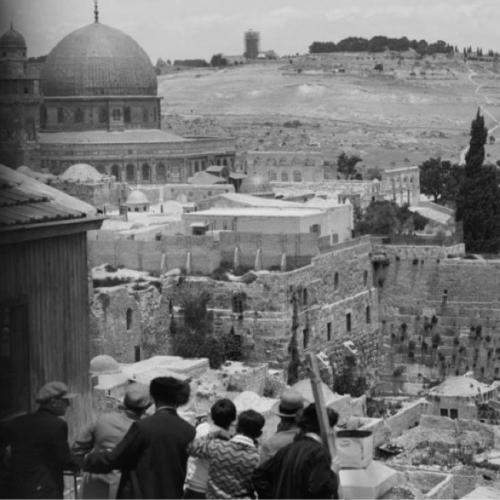

Hany recalls a visit to Jerusalem that solidified this connection: A relative took him to a spot in the Mount of Olives that overlooks the Old City and told him that this was his city. “I think that was the first time that I felt super connected. Because, to have him say that, and some of them in the family to be in that place at that time, it definitely like, created that bond, like this is a special memory that I'll never forget.”

Nevertheless, he was more aware of his connection to Jerusalem as a concept and a political struggle. This might be due in part to his grandfather, who never spoke to him about his experience fleeing the city in 1947. “He’s very comfortable talking about the history and the politics, but I think when it comes to personalizing that experience . . . he’s just not comfortable doing that. I think he finds it almost kind of trivial to place his personal suffering or his loss above . . . the larger scheme of the political historical situation.”

Ramy’s grandparents survived both the 1948 and the 1967 Wars. Just before the 1967 War, the family moved from their house in the Old City to Beit Jala, where the grandfather was offered a job. Before the 1967 War, Palestinians were able to move between East Jerusalem and Beit Jala with ease. Then after the war, the Israeli authorities conducted a series of censuses in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza (see The Census Story). Ramy’s grandparents and their children were registered in the Bethlehem census and received West Bank/Gaza IDs, as opposed to the Israeli-issued permanent-resident IDs that Palestinian Jerusalemites who were present inside the Israeli-declared municipal boundaries at the time carry.

When the political situation began to heat up in the 1970s and 1980s, his family was personally affected by it, and his grandparents, war survivors, began to look for a way out of Palestine. They eventually emigrated to the US. Ramy’s grandmother was left with lasting trauma that prevented her from ever returning to her homeland. Even after she became a US citizen, she could not bring herself to visit Jerusalem.

Ali’s grandfather was unable to tell his family why he left Jerusalem in 1948 (leaving his brothers behind), but he has stories of life in Jerusalem, which he shared with his grandson. He is unable to return to Jerusalem mainly for bureaucratic reasons; he had a Jordanian passport and was not granted a visa. The return was a task left to the grandson, Ali: “I was the first one [in the family] visiting Jerusalem after my grandfather left.”

The Struggle to Maintain a Connection to the City

In their attempt to limit the Palestinian population in the region out of demographic concerns, the Israeli government has constructed an elaborate system of laws, regulations, and policies that limit, curtail, or prevent Palestinians from returning, living in, and even visiting historic Palestine (see The Demographic Imperative).15 Some, like Dalal, were able to return because they married a Jerusalemite who had legal permanent-resident status. Others, like Ali and Hany, visit as tourists. Israeli law prevents Ali’s father and grandfather from even visiting, because they are considered refugees, and Israel denies refugees the right of return.

Dalal remembers visiting Lifta with her parents, who pointed out the homes of those they knew, including her grandparents’ homes. Her father started crying. She explains:

That really kind of stirred up even more emotions in me, and it really told me that I’ve always wanted to come back to live here, so my goal was always in the future to live here in some way. And I guess my husband just happens to be a Jerusalemite, and in an annoying kind of way he always tells me that he has provided me with my right of return.

Dalal’s return to Jerusalem has made her father exceptionally happy. He lives vicariously through her and is satisfied that someone connected to him still lives in the land of his ancestors. “So I think it’s sad, but it’s also hopeful that there’s always this connection kind of going back to the land and this connection of always going back, not only to Palestine in general, but to Jerusalem and to Lifta,” Dalal said.

Yara and Yasmeen were born to a Jerusalemite mother and a Yafawi father living in the UAE. Their maternal family lives in Jerusalem, and their mother still holds an Israeli permanent-resident ID, while her father’s family fled Jaffa in 1948 and found refuge in Jordan. Both sisters were born in Jerusalem and consider themselves Jerusalemites. “I lived all my life outside, but I always considered Jerusalem my home,” Yara said.

Her mother explains: “Both girls were registered [in the Israeli Population Registry] as having been born in Jerusalem. They had the documents [permanent-resident IDs] with them for five years, until the Israeli authorities tore them up on the [Allenby] Bridge. In so doing, they destroyed the girls’ legal right to live in the city. It was as though my daughters stopped existing.”

But for both Yara and Yasmeen, their connection to the city goes well beyond Israeli-issued documentation. They feel connected to the place and to the food and smells of the city, like the oranges and tangerines, and Jerusalem ka‘ek (bagels). For Dalal, even “Tapuzina,” the Israeli orange juice brand that was usually served in Palestinian weddings in Jerusalem, has a smell of home.

Every summer we used to go to Jerusalem; I had to get a visa from the Israeli embassy in Amman, Jordan. But when I turned 16, they stopped giving visas for people above the age of 16—that was in 2008. In 2010, I got a visa from the embassy, and they told me “this is your last year going in [to the country],” because then they changed the rules to 18 years old.

Yasmeen went through a similar process of visa rejection and being denied entry to Jerusalem. She and her sister believe that they were denied visas precisely because they were born in Jerusalem; in their view, the Israeli authorities want to prevent them from developing connections to the city or from thinking of establishing a life there.

But such measures did not deter these Jerusalemites. Yara and Yasmeen’s family, now living in the UAE, decided to buy property in a Caribbean country, through which they could obtain a “passport to go to Jerusalem,” the sisters explained. For them, that was the easiest way to return to Jerusalem, albeit as tourists carrying foreign passports.

Their mother, on the other hand, has a more complicated situation: She holds an Israeli permanent-resident ID while living in Dubai.

Every time I go to Jerusalem, I am afraid that my residency will be revoked. My ID photo is still of me when I was 29. Many things have changed since then, including the way I look. So, when I arrived at the bridge, they [the patrol officer] would tell me, every time, to go renew my ID in the office of the Ministry of Interior.

Yara’s mother explains why she has not renewed the ID: “because if I go renew it [the ID], they would revoke it [her residency].” Yara and Yasmeen’s mother shares that she knows many people who got their residency status revoked, including her own brother who lives in the US. “I know many people my age who had their residency revoked on the spot in the bridge because they live in Amman.”

For Margaret, 45, a Jerusalemite who has lived in Scotland for over a decade, Jerusalem is family. She works as a communications officer in Scotland, where she lives with her husband and children, but she made sure her half-Palestinian, half-Scottish daughter has Israeli citizenship, so that she could travel to and/or live in Jerusalem if she chooses to one day. In her eyes, Margaret sees that carrying an Israeli passport (which she got from her mother, a Palestinian citizen of Israel) grants her and her daughter an easier and more secure access to Jerusalem, sometimes even easier access than those living in Jerusalem, or in her daughter’s case, for even those who were born in Jerusalem.

Residential Status and the Cost of Living

The lengths to which Jerusalemites have been willing to go to maintain a connection with their hometown would be mind-boggling to many. Ask Jerusalemites about their relationship to the city, and you hear stories of hardship and a daily struggle for maintaining a basic right (being able to live in their place of birth), yet never do they suggest that they are willing to forego it. Their pride in their identifying as Maqdasis (Jerusalemites) is almost tangible.

Fatima comes from a middle-class family; both of her parents are educated and have steady jobs. After making 6 moves over a 10-year span in search of affordable housing within Jerusalem’s city limits, she and her family eventually settled in Kufr ‘Aqab. Technically, this Palestinian neighborhood is within the Israeli municipal boundaries, so she retains her all-important permanent-resident ID, but it is behind the Separation Wall and far from the Old City where her family is rooted (see The Separation Wall). She would like to buy property in Jerusalem inside the Separation Wall to protect her status and connection to the city, but the financial obstacles are daunting and include high overall costs, a required 30 percent down payment, and securing a mortgage from an Israeli bank, an impossibility for many Palestinian property holders in East Jerusalem. This is because Israel froze the registration and settlement of land there in 1967, making it difficult to even obtain a legal title on many properties since 90 percent of land is not registered in a modern system (see Land Settlement and Registration).

Like Fatima and many other Palestinian Jerusalemites, Moien and his wife were also forced by economic necessity to move to Kufr ‘Aqab, within the Israeli municipal boundaries of Jerusalem. Moien attributes this to Israel’s land policies, which he sums up as “more land, less people. This idea behind ‘more land’ was to keep it under the Israeli control and prevent Palestinians from building and developing and enjoying more housing opportunities.”

For Sani, a businessman with an academic degree, the deterioration in the economic life with the rise of the cost of living in Jerusalem cost him his family business. “I was the one who gave the family business away. I was crying with regret when I was emptying the shop [in preparation for its sale]. You know, we are talking about a business that survived 124 years. It was hard.”

In addition to the economic hardship that threatens their residency or the ability to even live in their city, Palestinian Jerusalemites also are witnessing changes in the city topography. Silwan, as an example, has been a major flashpoint in Israel’s attempt to maintain a Jewish majority in the city.16 For Moien, this could not be more personal: His family land is under threat of confiscation, because Israelis claim that they own part of it. The family has received numerous demolition orders and has been fighting the orders in Israel courts, causing a great deal of uncertainty and stress, not to mention enormous expenses. The case is still pending.

Fatima’s family is witnessing their city change before their eyes; they feel that their very presence is in the process of being erased. Her grandmother’s childhood home in the Moroccan Quarter was demolished for the sake of Judaizing the space, and they witnessed how Palestinian space around them in the Old City has decreased, while the space is increasingly being Judaized. “After the 1967 War, the family stayed in their home because it was a waqf property, but they were surrounded by Jewish neighbors. In the neighborhood [of her grandparents’ house] you see that everything is Jewish, you see the Jewish religion influence, because all of them [the neighbors] are religious.”

“I Am from Jerusalem”

Despite these attempts of forced displacement, alienation, and Judaizing the space, Palestinian Jerusalemites still feel deeply connected to the city. Fatima lives in Kufr ‘Aqab (outside the wall, inside the municipal boundaries), works in the neighborhood of Beit Hanina (inside the wall, inside the municipal boundaries), and socializes in Ramallah (outside Jerusalem, in the occupied West Bank), yet “I still feel more connected to Jerusalem [the Old City]. I feel that this is my home, something that I don’t feel toward Ramallah. I miss it if I don’t see it, and I don’t have that feeling for Ramallah [although she spends most of her social life there].” For Fatima, her special bond with Jerusalem, especially with the Old City, is a bond that was built through hardship and persistence. Fatima, who has family in the Old City, explains her complex feelings and connection to the place:

I lived all my life in Jerusalem. But after moving to Kufr ‘Aqab [outside the Separation Wall], I started feeling the distance from the city, although, geographically speaking, it’s not that far, but the checkpoint makes the distance grow further. And the thought of going to Jerusalem exhausts me. But at the same time, when I reach Jerusalem, I feel something special.

Ali has lived in many places and has more than one nationality, but he mostly feels “Maqdisi.” He explains: “I am a Jerusalemite Palestinian; these two [identities] go hand in hand.” And he adds: “Jerusalem has many beautiful things, it’s home to diverse religions and ethnicities; at the same time, it has many difficult and ugly things. Like occupation.” Despite the heartbreak that he feels when visiting Jerusalem, he feels at home there, something he did not experience living in the UAE, the UK, or any other place. “I only felt this way when I was in Jerusalem.”

Ali elaborates:

I know that as a Jerusalemite, I have the right to visit Jerusalem. This is a right for every Palestinian and every refugee and their descendants; they have the right to go to Palestine when they want, to live in Palestine when they want. I don’t know if I personally want to live in Jerusalem, grow old there, have kids, and die in Jerusalem [in its political circumstances now]. But yes, I would like to have the option to live there. Yes, I would want to live there, even for a short period, after we free Jerusalem.

Aside from the struggle in maintaining connection to the city, Jerusalemites feel a special bond to the city, one that cannot be explained in words.

Still, Fatima tries to explain: “There’s something to Jerusalem, you feel there’s a new thing and there’s some kind of a cheerful feeling you have when you go to Jerusalem [the Old City].” For others, it’s the simple things that make Jerusalem such a special place, such as a community custom of gathering with friends after 5:00 p.m. at Bab al-‘Amud and drinking tea.

Ramy, born to Palestinian immigrants in the US, describes the twists and turns of the narrow alleys of the Old City as though he had grown up there; in fact, he draws on his grandparents’ memory of the space. His connection to Jerusalem is through his visits to the city and his maternal grandfather. The history of the city is meaningful to him: “In Jerusalem, these walls have been there since the Ottomans . . . having a connection to the Old City feels very special to me. The fact that I have family members and grandparents who were born and lived there just feels very special and very unique to me. That’s where my sense of identifying with Jerusalem comes from.”

For Ramy, the city not only tells historic tales but offers him proof of identity. “The connection is the fact that my grandfather started a restaurant on Salah al-Din Street. . . . I definitely do identify as having roots and connections to the city. You can still see Attallah and Saliba family homes [his grandparents’ family names] in Haret al-Sa‘diyya till this day.”

Palestinian Jerusalemites do not view their life in the city as heroic; they simply want to live like normal people and do normal things, like owning property in a place they love, visiting family members, going to school without having to pass a checkpoint or being detained in the streets by Israeli security forces, and not feeling like they are an unwanted presence. Palestinian Jerusalemites persevere and work tirelessly to protect their connection and right to their city.

Whether in Jerusalem or abroad, Palestinian Jerusalemites remain deeply connected to the city through family, history, culture, heritage, stories, and collective trauma.

Notes

Nathan Krystall, “The Fall of the New City,” in Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighborhoods and Their Fate in the War, 2nd rev. ed., ed. Salim Tamari (Washington, DC, and Bethlehem: The Institute for Palestine Studies and Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, 2002), 84–141.

See, for example, Alina Korn, “From Refugees to Infiltrators: Constructing Political Crime in Israel in the 1950s,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 31 (March 2003): 1–22; Nadia Abu Zahra and Adah Kay, Unfree in Palestine: Registration, Documentation and Movement Restriction (London: Pluto Press, 2013).

In 2006, Sabella was elected to the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) to represent the district of Jerusalem. For more on these elections and their aftermath, and on representation in general, see Representation.

All quotations in this piece are from interviews conducted by the Jerusalem Story Team in September and October 2020, unless noted otherwise.

Salim Tamari, “Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources,” in Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840–1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, ed. Dalachanis Angelos and Lemire Vincent (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 490, 492–93.

Rana Barakat, “The Jerusalem Fellah: Popular Politics in Mandate-Era Palestine,” Journal of Palestine Studies 46, no. 1 (Autumn 2016): 9.

Barakat, “The Jerusalem Fallah,” 9.

Walid Khalidi, Dayr Yassin al-Jum’a, 9.4.48 [Deir Yasin, Friday, April 9, 1948] (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1999); Ofer Aderet, “Testimonies from the Censored Deir Yassin Massacre: ‘They Piled Bodies and Burned Them,’” Haaretz, June 16, 2017.

Krystall, “The Fall.”

Salim Tamari, ed., Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighborhoods and Their Fate in the War, 2nd rev. ed. (Washington, DC, and Bethlehem: The Institute of Jerusalem Studies and Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, 2002).

See note 2.

Areej Sabbagh-Khoury, “The Internally Displaced Palestinians in Israel,” in The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics, and Society, ed. Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury (Haifa: Mada al-Carmel, 2011), 26–46. For more on the methods used to ban the return of IDPs, see this source. See also Joseph Schechla, “The Invisible People Come to Light: Israel’s ‘Internally Displaced’ and the ‘Unrecognized Villages,’” Journal of Palestine Studies 31, no. 1 (Autumn 2001): 20–31. For the scope of the Palestinian properties seized, such as Bernard’s family’s, in West Jerusalem after 1948, see Dalia Habash and Terry Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property in the City,” in Jerusalem 1948, 167–99.

Abowd Tom, “The Moroccan Quarter: A History of the Present,” Jerusalem Quarterly File 7 (2000).

On September 30, 2020, a 12-year-old Palestinian boy named Muhammad al-Durra was shot dead in Gaza while his father tried helplessly to shield him with his body. The killing was filmed live by a Palestinian cameraman and the film was seen around the world, shortly after the outbreak of the Second Intifada, and became an iconic moment. For more background, see Talal Abu Rahma, “Behind the Lens: Remembering Muhammad al-Durrah, 20 Years On,” Al Jazeera, September 30, 2020.

See, for example, Lily Galili, “A Jewish and Demographic State,” Haaretz, June 27, 2002; Rassem Khamaisi, “Jerusalem Demography: History, Transitions, and Forecasts,” Jerusalem Quarterly 82 (Summer 2020): 110–29; Hannah Mermelstein, “Overdue Books: Returning Palestine’s ‘Abandoned Property’ of 1948,” Progressive Librarian, no. 45 (Winter 2016/17): 66–86.

Nadav Shragai, “Jerusalem: Delusions of Division,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs; see chapter 2, “The Demographic Problem: A Different Approach.”