Israeli settlements are rapidly expanding in and around East Jerusalem, even inside Palestinian neighborhoods, threatening to turn the city into one strictly for Jews.

Credit:

Peoples Dispatch

Judaizing Jerusalem: Jewish Settlements Are Soaring in and around the City

Snapshot

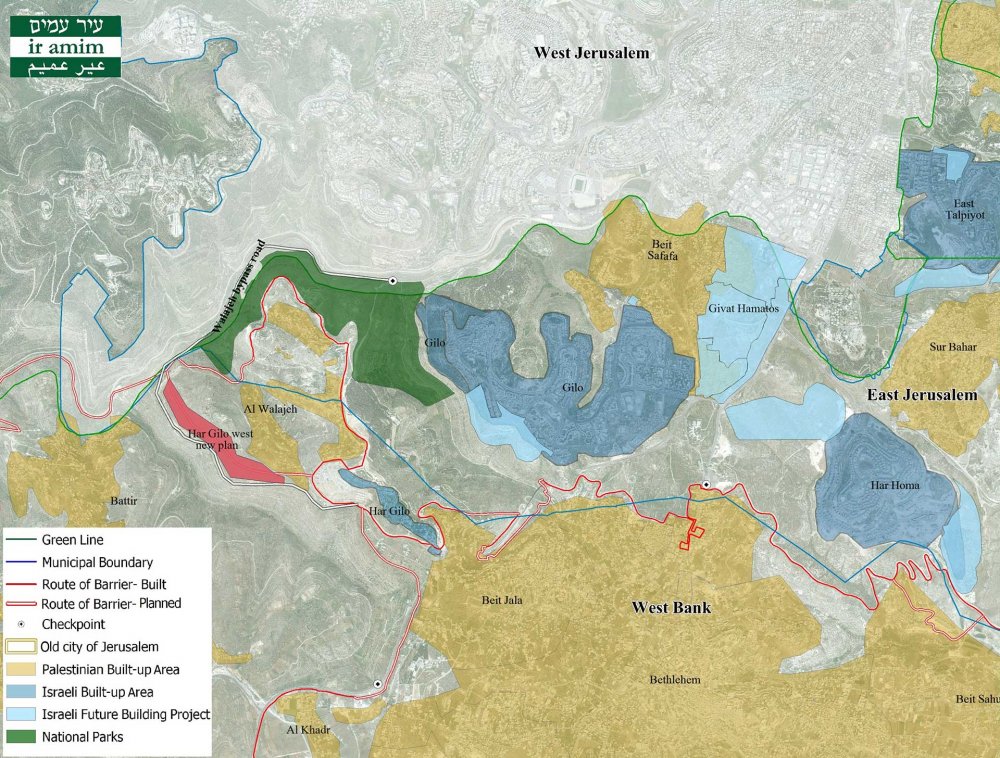

This year has seen the advancement of dozens of different settlement construction plans in and around East Jerusalem. Combined, these plans threaten to further fragment and asphyxiate Palestinian localities and neighborhoods in the city and its environs.

In early June 2023, under US pressure, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delayed a critical planned hearing on the E1 Development Plan (or East 1, referring to the Israeli designation of the area east of Jerusalem deep in the occupied West Bank), which would bifurcate the occupied West Bank. Days later, however, Israel informed the US that it will announce thousands of new settler homes in the wider Jerusalem area at the end of June.1

“There’s a rule of thumb that whenever Netanyahu does something that can be perceived as conciliatory, he makes up for it by doing something horribly outrageous somewhere else,” Israeli attorney and East Jerusalem specialist Daniel Seidemann said of this latest development in settlement construction.2

E1 is not the only settlement plan threatening the West Bank’s geographic contiguity and the Palestinian fabric of the greater Jerusalem region. Dozens of construction plans for Israeli-only settlement housing at various stages of completion are currently underway across and around East Jerusalem.

“As much as E1 is detrimental and has serious ramifications on Palestinian livelihood and self-determination, at the same time, this slew of settlement plans within East Jerusalem has also the very same impact because it’s a cumulative repercussion,” said Amy Cohen, executive director at Ir Amim, an Israeli Jerusalem-focused nonprofit.3 She added: “If you put them all together, you have thousands and thousands of housing units that are being advanced in settlements.”

From the beginning of 2023 through June, Israel advanced 22 settlement outline plans with a total of 16,060 housing units in East Jerusalem, according to Ir Amim.4 The following are some of the most extensive.

Settlement inside Palestinian Neighborhood: Nof Zahav/Nof Zion/Jabal Mukabbir

On May 8, 2023, the Jerusalem District Planning Committee was scheduled to discuss filing objections to the Nof Zahav settlement plan for 100 housing units and 275 hotel rooms in the Palestinian neighborhood of Jabal Mukabbir in southeastern Jerusalem, but it was removed from the committee’s agenda and no new date has been set. The plan is an expansion of Nof Zion, an existing luxury settlement of 95 housing units that is located in Jabal Mukabbir and has been home to nationalist-religious Jewish families since 2011. Kilas Investment Corporation, an overseas company owned by Israelis, initiated the building plan.5

According to Ir Amim, if the plan is approved, “Nof Zion is slated to become the largest settlement in the heart of a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem.”6 Jabal Mukabbir is one of the largest Palestinian neighborhoods in the city.

Severing the Northern West Bank from Its Southern Flank for Palestinians: E1

The E1 Development Plan consists of 3,412 housing units situated between East Jerusalem and the Ma‘ale Adumim settlement bloc located in the occupied West Bank, east of the city.

The E1 plan would expand this settlement bloc to contain (another) industrial park, a new settlement called Mevaseret Adumim, thousands of new settlement homes, hotels, and a police station (already built).

Construction here would divide the West Bank in half and cut it off from East Jerusalem, thereby eliminating any possibility of establishing a contiguous Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.7

Settlement in Supposed “Alternative Capital” of Palestine: Kidmat Tzion/Abu Dis

The notorious settler organization Ateret Cohanim along with the Tenants’ Association—which has been building settlements in East Jerusalem since 1926—are raising funds for a new settlement, Kidmat Tzion (Zion), in the Deir al-Sanah area of Abu Dis, a large Palestinian neighborhood southeast of Jerusalem just outside the municipal boundaries, separated from the city by the Separation Wall (see The Fragmentation of Jerusalem’s Eastern Palestinian Towns).8 It is slated to start off with 384 housing units.9 In fact, during the 2023 Jerusalem Day, an annual event held in early June marking Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967, Ateret Cohanim raised more than $220,000 for the Kidmat Tzion plan.

Abu Dis has often been touted, especially by the Trump administration and Israeli commentators, as a place where a Palestinian capital could be envisioned in a scenario of two states, or some kind of modest autonomy for Palestine. For them, it is a given that municipal East Jerusalem is off the table, so only something outside the city boundaries is conceivable.10

Ateret Cohanim openly acknowledges that its goal for building in Abu Dis is to “prevent the Arab takeover of the city’s eastern neighborhoods.” In documents it filed with Jerusalem’s Planning Committee, the organization claimed: “Palestinian institutions in Abu Dis were built with the vision of turning the town into the capital city of Palestine.”11 As a result, “The significance of establishing and developing the neighborhood is to create a shield for Jerusalem against Palestinian ambitions.”

New Talpiot Hill and Giv’at HaShaked/Sharafat, Beit Safafa

In September 2022, the District Planning Committee approved the deposit of objections to the construction of Giv’at HaShaked, a new settlement consisting of 695 housing units in the Palestinian neighborhood of Sharafat, Beit Safafa. However, the committee is expected to begin the New Talpiot Hill plan, which calls for 3,500 housing units and 1,300 hotel rooms along Hebron Road, thereby expanding the settlement of Giv’at Hamatos.

Coupled with the Lower Aqueduct plan, these projects will engulf Sharafat, Beit Safafa, in a maze of Israeli settler construction and cut off Jerusalem’s southern tip (the Palestinian neighborhood of Beit Safafa) from the West Bank. This would forever preclude the possibility of incorporating Beit Safafa into any kind of future Palestinian state.

Har Gilo West/al-Walaja, Battir

In November 2022, the Higher Planning Council discussed objections to the plan for a new settlement, Har Gilo West, entailing the construction of 560 housing units on 205 dunums of land in Area C, belonging to the Palestinian town of al-Walaja, located south of Jerusalem in the West Bank. Israel considers the plan to be an expansion of the Har Gilo settlement, which is wedged between the Palestinian localities of al-Walaja and Beit Jala/Bethlehem, but the European Union Representative for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) disagrees, categorizing it as a new settlement.12 It is only the first phase of a much larger future plan that is ultimately envisioned to take up an area of 940 dunums.

If built, Har Gilo West would also entail construction of a new section of the Separation Wall, a section that will complete the encirclement of al-Walaja, already surrounded on three sides by the wall, and block any potential future expansion. The settlement would also sever al-Walaja from Battir and consume the only remaining green areas left for the Palestinian city of Bethlehem.

The Separation Wall splits al-Walaja in two, cutting off villagers from their agricultural lands. Despite this, residents have been able to use bypass road 385 to access their lands.

Yet, in May 2023, the Jerusalem Municipality announced that work to relocate the al-Walaja checkpoint on the bypass road would soon begin. Relocating the checkpoint will completely block off villagers from their agricultural lands,13 while expanding the bypass road would validate the new Har Gilo West settlement plan.

The new settlement, which would double the size of Har Gilo, would occupy a nearby hill that is less than a mile from the ancient, agricultural, and terraced Palestinian village of Battir, a UNESCO world heritage site. The village’s estimated 5,000 residents depend on a complex and ancient natural irrigation system that would be threatened by the planned construction.14

In a joint statement released in September 2022 in advance of a public meeting on objections to the plan for Har Gilo West, Israeli NGOs Ir Amim and Bimkom highlighted the political significance of Har Gilo West:

Beyond its destructive impact on the Palestinian village of al-Walaja, the plan’s ramifications on the prospects of any viable political agreement should be seen on par with Israeli construction in E1. Both plans contribute to the Israeli government’s acceleration of de-facto annexation of the West Bank, in particularly the Greater Jerusalem area, while carrying dire ramifications on Palestinian human rights. The advancement of Har Gilo West joins a spate of cumulative Israeli measures taking place along the southern flank of East Jerusalem and its surroundings in a bid to consolidate Israeli control and increase territorial contiguity with the Gush Etzion settlement bloc.15

Erasing the Green Line and Severing East Jerusalem from Bethlehem: Lower Aqueduct/Umm Tuba

The Lower Aqueduct plan calls for building a new settlement with 1,465 housing units on about 186 dunums of land, the majority of which is private Palestinian land.16 The settlement would straddle the Green Line, with half the area inside the Green Line and half outside it in East Jerusalem, thereby furthering the erasure of the historic line. A new settlement (and only the second in 30 years), it will link the settlement of Har Homa, built in the 1990s during the Oslo years on land expropriated from Umm Tuba, with that of Giv’at Hamatos, along the southern edges of kibbutz Ramat Rachel. The area was initially conceived as a commercial center for Umm Tuba until Har Homa residents protested fiercely in 2020.17

The project also aims to build an access road on private Palestinian land belonging to residents of the nearby Palestinian neighborhood of Umm Tuba.18 According to the website Terrestrial Jerusalem, this settlement has enormous strategic implications:

The Lower Aqueduct Plan aims at linking Har Homa to the newly approved settlement of Givat Hamatos, and at creating an almost uninterrupted contiguity between Har Homa West, Ahuzat Nof Gilo and Har Gilo West. The cumulative impact of these plans is to create a continuous built-up buffer, sealing East Jerusalem off from its sister city, Bethlehem. Viewed in context, the Lower Aqueduct Plan is a significant component in a strategic thrust aimed at consolidating sole Israeli rule over East Jerusalem, and cutting it off from its environs in the West Bank.19

On May 30, 2023, the District Planning Committee discussed objections to the plan, which has been fast-tracked, but has yet to reach final decision on approval.

Israel’s Ultimate Goal for Jerusalem: A Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem

Along with these new settlements, expansions of the existing settlements of Ramot Alon A and B, Pisgat Ze’ev, Har Homa, East Talpiot, Ramot, Giv’at Hamatos, and the French Hill are also in the works.

For Ir Amim’s Cohen, while the significant acceleration in settlement building in 2023 is part of ongoing trends that began in mid-2021, the increase can also be attributed to Israel’s new far-right government.

“You have ultranationalists and settler activists that are in the higher political echelons of the government, and they are going to push forward their agenda as much as possible,” Cohen told Jerusalem Story.

Yet, for Seidemann, this perspective gives the new coalition too much credit.

“These plans have been worked upon for years,” Seidemann said. “This is already in the DNA of official Israel.”

No matter the source, Cohen emphasized that intensifying settlement construction not only dashes hopes of a Palestinian state by consolidating Israel’s hold over East Jerusalem, but also exacerbates the area’s housing problem.

“On one hand, you’re depleting and exhausting all of the lands within East Jerusalem that could serve the local Palestinian population,” Cohen said. “At the same time, it also serves another purpose of ultimately pushing Palestinians out of the city.”

Notes

Jacob Magid, “Israel Tells US It Will Advance Plans for Thousands of Settlement Homes in Late June,” Times of Israel, June 12, 2023.

Interview conducted by the author with Daniel Seidemann on June 14, 2023, Jerusalem. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations in this Feature Story by Seidemann were taken from this interview.

Interview conducted by the author with Amy Cohen on June 13, 2023, Jerusalem. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations in this Feature Story by Cohen were taken from this interview.

Amy Cohen, “Major Acceleration of Israeli Settlement Activity since January 2023 Juxtaposed with Deprivation of Palestinian Human Rights,” Ir Amim, June 15, 2023.

Amy Cohen, “District Planning Committee Set to Discuss Nof Zahav Settlement Plan Next Week,” Ir Amim, May 2023.

Cohen, “District Planning Committee Set to Discuss Nof Zahav.”

Amy Cohen, “Israeli Government Resumes Advancement of E1 Settlement Plans for 3412 Housing Units,” Ir Amim, February 24, 2023.

Shalom Yerushalmi, “Jerusalem Planners Give Initial Approval to Jewish Enclave in Palestinian Abu Dis,” Times of Israel, May 22, 2023.

Cohen, “Major Acceleration of Israeli Settlement Activity.”

"Abu Dis, an Unlikely Capital for a Future Palestinian State,” Asharq al-Awsat, January 29, 2020.

Yerushalmi, “Jerusalem Planners Give Initial Approval.”

“Report on Israeli Settlements in the Occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem (January–December 2022),” Office of the European Union Representative (West Bank and Gaza Strip, UNRWA), May 25, 2023.

Amy Cohen, “Impending Relocation of al-Walaja Checkpoint to Block Palestinians from Agricultural Lands,” Ir Amim, May 12, 2023.

Ilon Ben Zion, “Planned Israeli Settlement Threatens West Bank UNESCO Site Ecosystem,” Associated Press, June 20, 2023.

Cohen, “Impending Relocation of al-Walaja Checkpoint.”

“Insiders’ Jerusalem: Inside the Surge in Settlement Activities in East Jerusalem—Monitoring Developments, Understanding Patterns,” Terrestrial Jerusalem, January 22, 2022.

As reported in Haaretz, one man summarized objections to the plan as follows: “It’s dangerous for the girls. We need to live separately. We need to keep [the residents of Umm Tuba] away from us. They would harm our children and we need to build a wall between us and them.” According to others present, another resident said she would only want to see Arabs up close “as shepherds with sheep.” Another reportedly said: “The State of Israel belongs only to the Jews, and Arabs need to be drawers of water and hewers of wood,” a reference from the Book of Joshua referring to manual laborers. Nir Hasson, “Business Center for E. Jerusalem Arabs Halted over Jewish Neighbors’ Objections,” Haaretz, February 12, 2020.

Amy Cohen, “District Planning Committee Approves Lower Aqueduct Plan for Deposit for Objections,” Ir Amim, July 29, 2022.

“Insiders’ Jerusalem.”