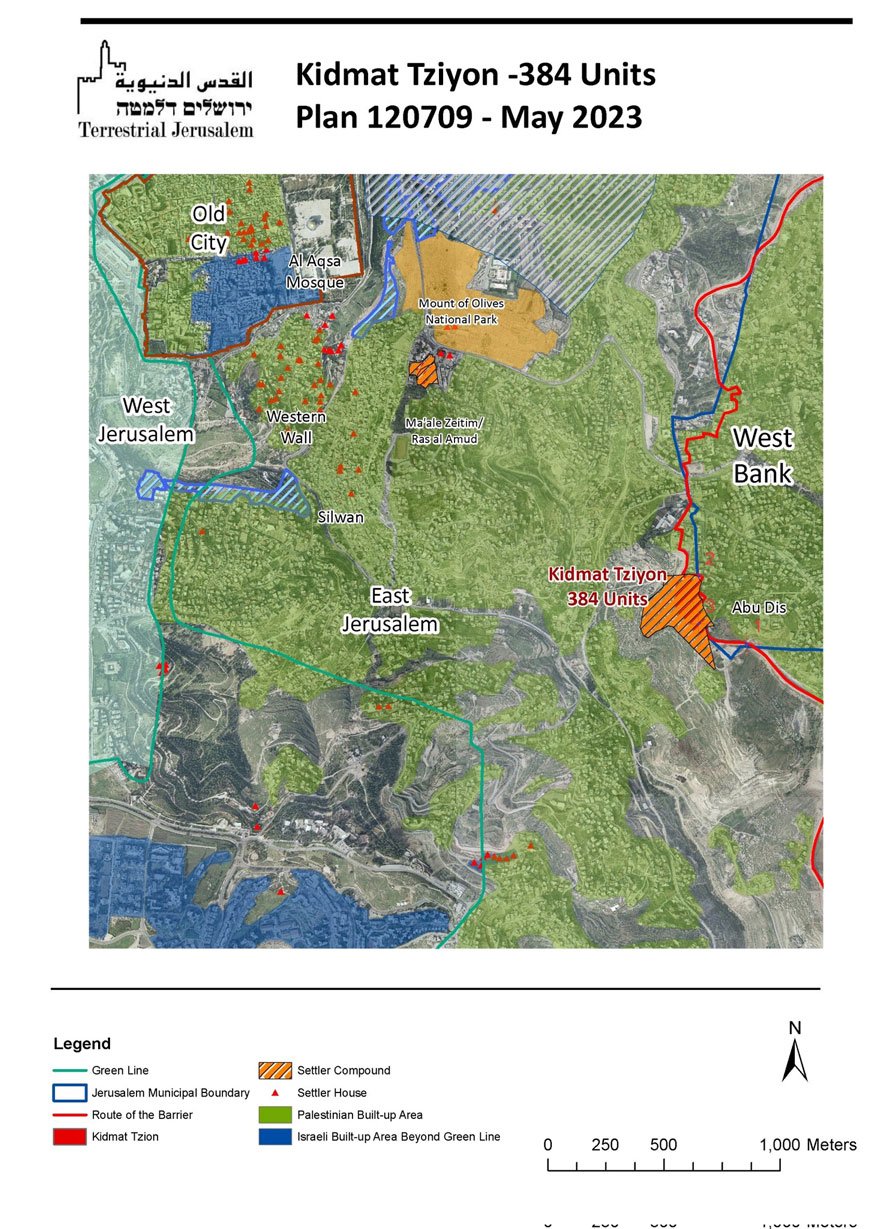

Just two days after Hamas launched Operation al-Aqsa Flood and Israel declared war on Gaza, the Jerusalem municipality’s District Planning Committee quietly approved the fast-tracked Kidmat Tzion settlement plan (Plan 101-0120709) for deposit with conditions. What this means is that the committee allows the plan to be published in newspapers for public review and objections, after which 60 days will be allocated for the hearing of any objections. Meanwhile the conditions identified must be resolved. According to Haaretz, “the proposal is being pushed forward with exceptional speed.”1

The decision was not made public until October 16.

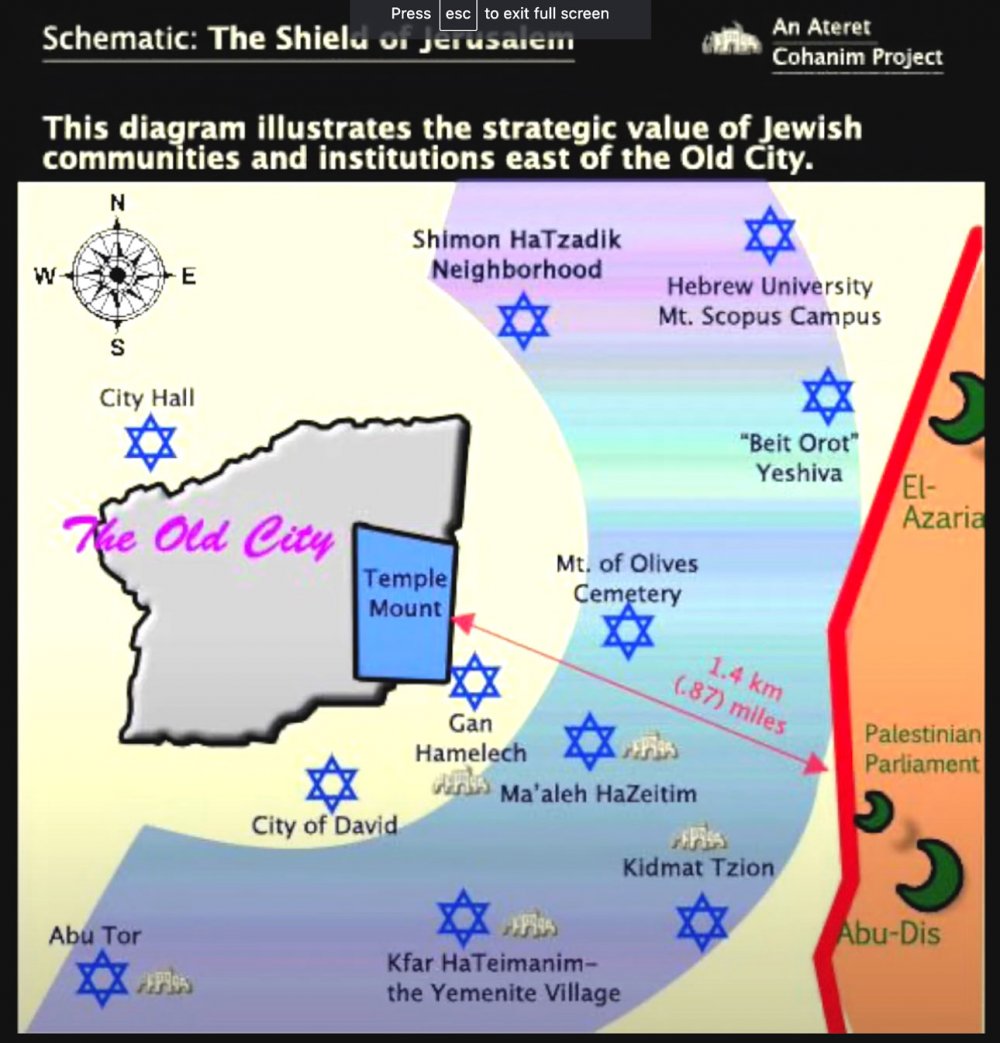

The new settlement is set to be built in the heart of Ras al-Amud, a Palestinian neighborhood at the eastern edge of East Jerusalem, inside the municipal boundary and the Separation Wall. Its location is on a mountainside ridge that faces the Old City and the Mount of Olives, abutting the Jerusalem side of the wall.

Currently, 11 Jewish families with some 70 children occupy seven units on the site in two buildings and three more “makeshift” buildings.2