Overview: Israeli Settlements in and around Jerusalem

Credit:

The Three Israeli Settlement Rings in and around East Jerusalem: Supplanting Palestinian Jerusalem

Snapshot

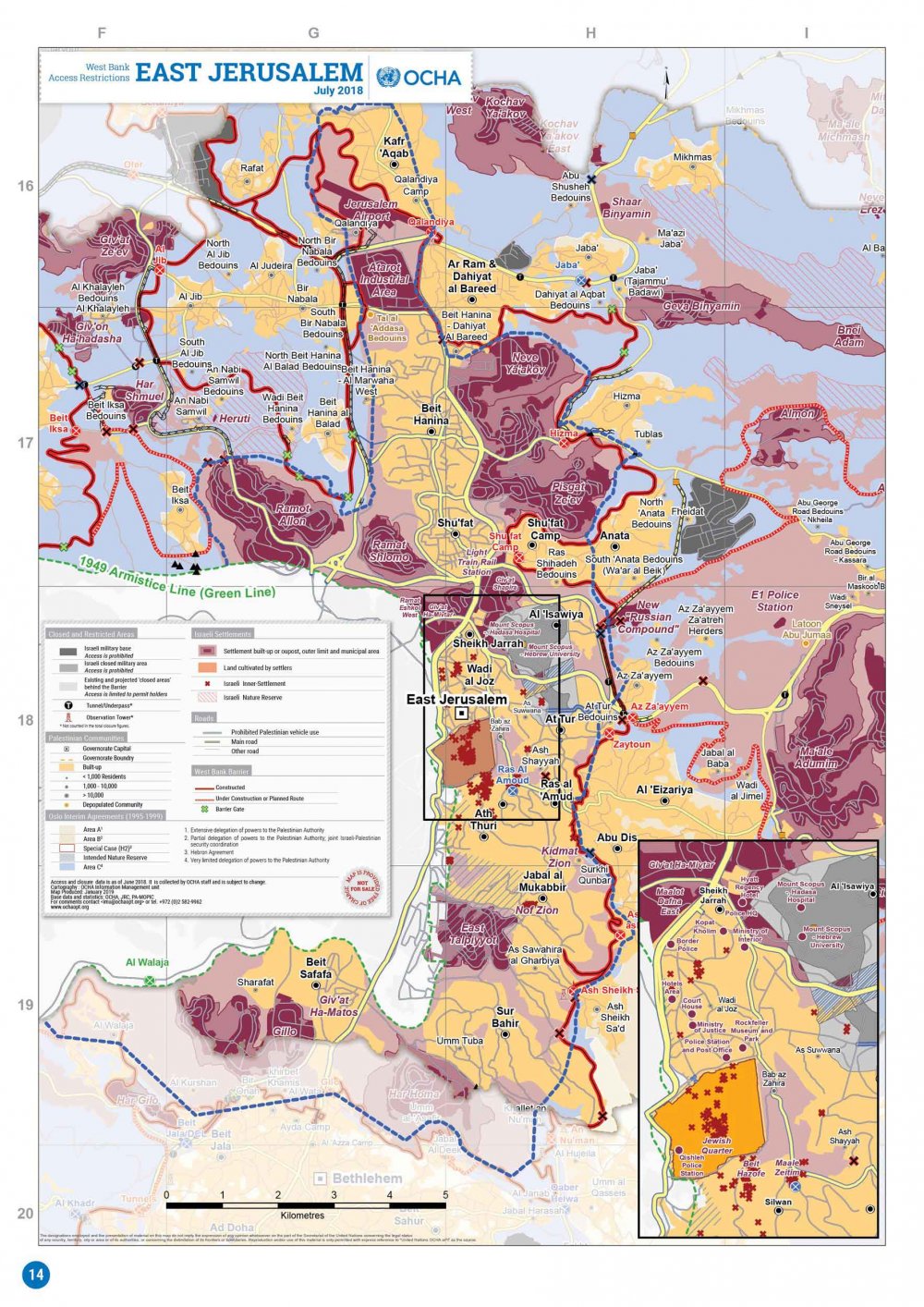

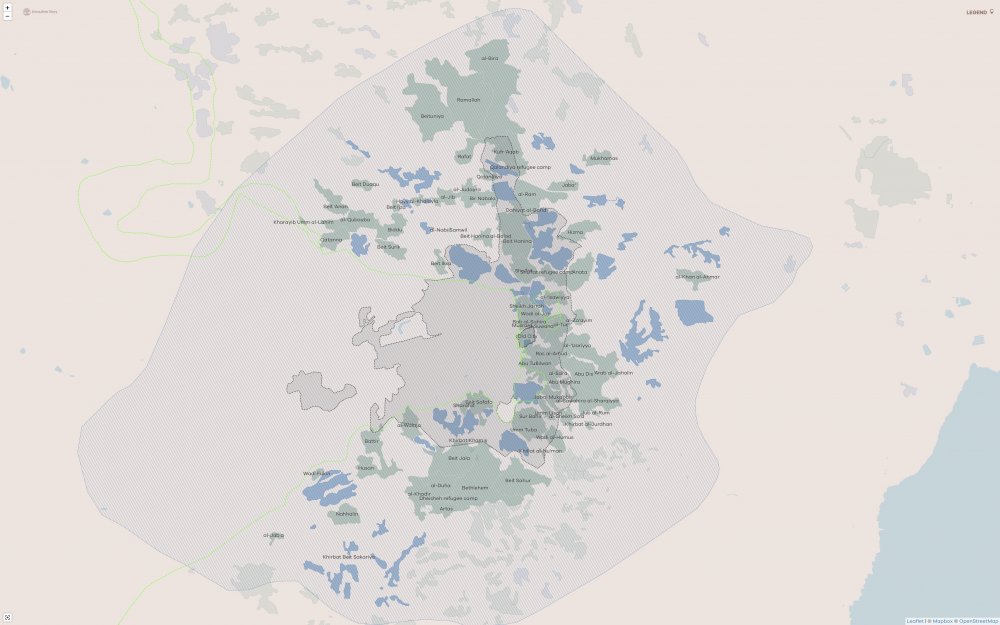

This Backgrounder addresses the Israeli settlement enterprise in Jerusalem, the eastern half of which Israel occupied in 1967. It sketches the present geopolitical reality formed by Israeli settlement expansion in and around East Jerusalem, showing how Israel planned the settlements strategically in three consecutive layers, or rings. Israel has used this geopolitical construction of settlements—accompanied by the Separation Wall, a network of checkpoints, bypass roads, and a planning regime—to establish “facts on the ground” that transform the geography, demography, and historic cultural character of the city and its environs. Ultimately, the settlements contribute to expanding greater Israeli control over occupied Palestinian lands, dismantling the possibility of a contiguous and viable Palestinian state in the West Bank with East Jerusalem as its capital. Beyond territorial contiguity, settlements and their accompanying infrastructure ensure the dispossession, fragmentation, de-development, and ghettoization of Palestinian communities.

The ongoing process of building Israeli settlements in the West Bank (which includes East Jerusalem) since its occupation following the 1967 War reflects the settler-colonial agenda of the Zionist movement across historic Palestine. Indeed, Zionist settlement in what is today Israel was inextricable from the dispossession and exile of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in the years preceding and immediately following the state’s founding (see The West Side Story).

Yet the term settlements today is usually used to refer to the illegal Israeli colonies built in the Golan Heights and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.1 These include residential localities inhabited by Israeli Jews or newly arrived Jewish immigrants, as well as nonresidential localities such as industrial zones, tourist sites, and national parks. These may be authorized variously by the Israeli government, the Israeli Jerusalem municipality, or by private settler organizations with the cooperation of the state and the municipality.2

As this Backgrounder will show, Israel has been designing settlements in and around Jerusalem strategically. That is, since 1967, it has been implementing a planning and development strategy whereby Palestinian East Jerusalem would be fragmented and suffocated by three settlement rings, thereby dispossessing Palestinians and subjecting them to destructive de-development policies that render their living spaces into living ghettos. Ultimately, the settlement planning regime ensures the radical reengineering of the geography, demography, and cultural character of Jerusalem with the aim of Judaizing it.

Indeed, since 1967, Israeli settlements built in Jerusalem and its surroundings, as in the rest of historic Palestine, have had disastrous outcomes on the lives of Palestinians, their spaces of living, and their collective future. On a daily basis, Israeli settlements devastate Palestinians’ quality of life, restricting their movement,3 their ability to work in fragmented and crippled economies,4 their ability to find and afford housing, and their overall health and well-being.5 Through building settlements, Israel has been subjecting Palestinian families to multiple modes of dispossession, including confiscating their rightfully owned lands, properties, and natural resources,6 as well as demolishing their homes, forcibly displacing them,7 and sanctioning violent vigilantism against them by Jewish Israeli settlers.8 In this way, the process of settlement building is fundamentally predicated on the dispossession of Palestinians and the destruction of their collective fabric and communal capacity—cities, villages, neighborhoods, and individual homes.

Israeli settlements in and around East Jerusalem: Facts and numbers

Today, there are about 150 state-authorized settlements and more than 140 settlement outposts throughout the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.9 State-authorized settlements are fully developed with permission from the Israeli government, while settlement outposts are unauthorized, built on Palestinian lands by extremist Israeli Jews without government permission. Often, they are the seedling for what later becomes a forest, or a large settlement community. While illegal under Israeli law, the government largely overlooks the activities of these extremist groups and for the most part recognizes the settlement outposts at a later stage. In addition, many outposts are built within Palestinian neighborhoods by settler organizations with the cooperation of the state and municipality.

Within the boundaries of the Palestinian Jerusalem governorate (Muhafazat al-Quds), which covers Jerusalem and its environs (see Where Is Jerusalem?), there are:

- 26 state-authorized settlements within the Israeli-imposed municipal boundaries and outside of them;10

- 9 settlement outposts in areas of Jerusalem outside the city’s municipal boundaries (i.e., in the rest of the occupied West Bank);11

- 9 settlement outposts in Palestinian neighborhoods inside the municipal boundaries, within and around the Old City.12

The Jerusalem region as a whole—referred to by Israeli officials as “Greater Jerusalem,” although this designation includes parts of the governorates of Ramallah and Bethlehem (see Israel’s Vision of a Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem)—hosts a large network of so-called urban, suburban, and rural settlements that surround the city. This area includes four of the five largest settlements in the West Bank: Ma‘ale Adumim, Pisgat Ze’ev, and Ramot—each housing more than 40,000 Israeli Jewish settlers—and the major Beitar Illit settlement in the Bethlehem area south of Jerusalem, with more than 50,000 settlers.

As of 2022, the Israeli settler population across the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, exceeds 680,000 people. More than 320,00013 of them reside in the larger Jerusalem region, and more than 200,00014 reside within the expanded Israeli municipal boundaries of East Jerusalem.

From Facts on the Ground to Impacts on the Ground

The construction of settlements in and around Jerusalem must be understood within the geopolitical logic that grants Israel what Jeff Halper of ICAHD calls a “matrix of control”15 over occupied Palestinian land. With Israel’s occupation and de facto annexation of 71 km2 of East Jerusalem in 1967, the process of confiscating Palestinian land and building settlements on it was immediate in and around the city. This process has been carried out since 1967 within a larger strategic planning regime that has gained political dominance by creating “facts on the ground” through the building of settlements, bypass roads, and the Separation Wall. Collectively, these “facts on the ground” reshape the character of occupied Palestinian lands, cementing Israeli territorial expansion and control by expanding Israel’s administrative, juridical, military, and security presence over the settlements.

Israel’s planning of settlements in and around Jerusalem can be observed in the extensive network of settlement blocs that are attached to each other by jurisdictional or transportational infrastructure, providing them with territorial contiguity in what are known as settlement belts. To understand these patterns in and around Jerusalem today, and the reality they produce for Palestinian communities, it is important to observe how Israeli settlement belts take the shape of three rings that encircle Jerusalem’s historic core, the municipally controlled area, and its surrounding hinterlands:

- The Inner Ring: Settlement belt in East Jerusalem within the unilaterally expanded Israeli municipal boundaries

- The Outer Ring: Settlement belt around Jerusalem outside the municipal boundaries, within the larger occupied Palestinian West Bank

- The Core Ring: Settlement belt within Palestinian neighborhoods in and around the Old City of Jerusalem

These three rings limit the growth of Palestinian localities, serving to also sever them from one another and from their historic city: Jerusalem. As a result, this reality creates “a psychological feeling among the Palestinians of living in a ghetto, in order to demoralize the Palestinians and encourage them to emigrate and consequently facilitate Israeli control of the city.”16

Settlement planning, construction, and expansion in East Jerusalem functions according to legal and planning schemes that maintain the three rings in the greater Jerusalem region. Despite the different legal and administrative mechanisms entailed in each ring, it is one coherent system predicated on the dispossession and displacement of Palestinians in Jerusalem in order to replace them with Jewish settlers, ultimately fulfilling the Zionist agenda of Judaizing Jerusalem.17 Indeed, Israel has expropriated 35 percent of the land of East Jerusalem for the development of settlements, but it limited Palestinians to building on only 13 percent of the same area.18 And while urban plans focus on expanding settlements with more territory and housing units, Israel rarely approves Palestinian building permits in East Jerusalem, making them almost impossible to obtain.19 In fact, the Jerusalem municipality denies at least 93 percent of all building applications from Palestinians in the city.20 As a result, many Palestinians build their homes without municipal approval, which Israel then uses as a pretext for demolishing them.21

The “facts on the ground” logic entailed in settlement expansion thus inherently and necessarily entails the following destructive impacts on Palestinian communities:

Dispossession:

- Confiscation of Palestinian private and public lands for the purpose of settlement construction and expansion

- De facto annexation of land for future settlement expansion through the construction of the Separation Wall

- Expropriation of houses and properties, and their transferal to the ownership of the Israeli state or private settler organizations

Displacement:

- Expulsion of families from their homes for the purpose of replacing them with Jewish settlers

- Demolition of homes and/or entire villages for the purpose of settler expansion

De-development:

- Besiegement of Palestinian localities, preventing the possibility of natural demographic growth

- Prohibition of access to farmlands and natural resources that become solely reserved for settlement usage

- Expropriation of Palestinian natural resources, including water and farmland

- The imposition of zoning plans that prohibit Palestinian construction of homes and public facilities, thus facilitating settlement expansion and demolition campaigns of Palestinian-owned structures

- Unequal distribution of services between settlements and Palestinian neighborhoods, if not the total denial of these services to Palestinian communities; this includes supplying settlements with four times more water than Palestinian villages,22 often forcing Palestinians to purchase water from settlements at exorbitant costs23

- Pollution of Palestinian localities by Israeli settlers, including through dumping sewage and degrading air quality24

Fragmentation and ghettoization: The geographic planning of settlements and their infrastructure in a way that fragments the continuous geographic fabric of Palestinian localities, turning them into isolated cantons and ghettos, between which movement is heavily restricted for Palestinians

Violence: The sanctioning of settler violence against Palestinians, especially among extremist settlers who live nearby Palestinian homes and neighborhoods. These settlers are armed and dangerous, and are protected by the police who also routinely inflict brutal violence on Palestinians.

The Three Israeli Settlement Rings in and around East Jerusalem: A Closer Look

1. The Inner Ring: Settlement belt within the expanded Israeli municipal boundaries

The Inner Ring consists of state-authorized settlements in East Jerusalem on confiscated Palestinian land under Israeli municipal jurisdiction. Fifteen such settlements exist today within the expanded municipal boundaries of Jerusalem (see Map 2 and Table 1). With the Jewish Quarter in the Old City at its core, the Inner Ring settlement belt is connected through an infrastructure of roads and tunnels, and extends from the southeastern settlement of Gilo all the way to the northern industrial settlement of Atarot.

Table 1: The Inner Ring of settlement neighborhoods

| Settlement name | Year of land expropriation and beginning of construction25 | Location in the ring in relation to the Old City | Settlement type26 | Palestinian localities dispossessed for settlement construction27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jewish Quarter | 196828 | Within the Old City | Settlement neighborhood in the Old City | Maghariba neighborhood, Sharaf neighborhood |

| Mount Scopus enclave | 1968 | Around the Mount Scopus enclave29 | Settlement neighborhood | Shu‘fat, al-‘Isawiyya, Sheikh Jarrah, Wadi al-Joz |

| French Hill (Givat Shapira) | 1968 | North of Mount Scopus enclave; northeast of Sheikh Jarrah | Settlement neighborhood | Shu‘fat, al-‘Isawiyya, Sheikh Jarrah, Wadi al-Joz |

| Ramat Eshkol | 1968 | North “hinge”30 | Settlement neighborhood | – |

| Givat HaMivtar | 1968 | North “hinge” | Settlement neighborhood | – |

| Ma’alot Dafna | 1968 | North “hinge” | Settlement neighborhood | – |

| Ramot (Ramot Allon) | 1970 | Northeast | Settlement neighborhood | Beit Iksa, Lifta |

| Atarot (incl. airport) | 1970 | North | Industrial settlement (being developed into a residential settlement) | Beit Hanina, al-Ram, Dahiyat al-Barid |

| Neve Ya’akov | 1970 | Northwest | Settlement neighborhood | Beit Hanina, Hizma, al-Ram |

| East Talpiot | 1970 | South | Settlement neighborhood | Sur Bahir, al-Sawahira al-Sharqiyya, Silwan |

| Gilo | 1970 | Southeast | Settlement neighborhood | Sharafat, Bethlehem, Beit Jala, Beit Safafa, al-Walaja |

| Pisgat Ze’ev | 1980 | Northwest | Settlement neighborhood | Beit Hanina, Shu‘fat, Hizma |

| Ramat Shlomo | 1990 | Northeast | Settlement neighborhood | Shu‘fat, Beit Hanina, Beit Hanina al-Balad |

| Givat HaMatos | 1991 | South | Settlement outpost (being developed into a settlement neighborhood) | Sharafat, Beit Safafa |

| Har Homa | 1991 | South | Settlement neighborhood | Umm Tuba (Jabal Abu Ghuneim), Beit Jala, al-Walaja, Beit Sahur, Sur Bahir |

Note: This list does not include settlement outposts built in Palestinian neighborhoods (the Core Ring), nonresidential Israeli settlements, touristic settlements, and national parks, or nonresidential areas that Israel controls like Ramat Rachel area, Jaffa Gate, and Ben Hinnom Valley, all of which contribute to making up the network of the ring.

Settlements in the Inner Ring mostly take the shape of “urban” or “settlement neighborhoods,” with some nonresidential settlements as well. The location of settlements within the Israeli municipal boundaries means that despite their illegality under international law, Israel treats them as Israeli neighborhoods. These settlements are administered by, and receive services, resources, and budget allocations directly from, the Israeli Jerusalem municipality. In contrast to the settlements in the remainder of the occupied West Bank, these settlements do not have fences surrounding them or security guards at their entrances. This also gives the impression that they are part of the city’s urban landscape, as anywhere in Israel of pre-1967 borders, such as in West Jerusalem or inside the Green Line.

Directly northeast of the Old City, the expansive Mount Scopus enclave includes Hebrew University and Hadassah Hospital,31 and while this enclave is on the eastern side of the city, it existed before 1967 and is considered to be legally within the boundaries of the Green Line (see Map 6, “Jerusalem Divided by the Green Line (1949),” in Where Is Jerusalem?). The establishment of the settlements of Giv‘at Ha Mivtar, Ramat Eshkol, and Ma’alot Dafna following the 1967 War expanded the Mount Scopus enclave, connecting it to West Jerusalem. The settlements simultaneously fragment Palestinian spaces, as they lie between Sheikh Jarrah to the south and Shu‘fat to the north, restricting the growth of both Palestinian neighborhoods, whose existence traces back to long before 1967.

Due to settlement expansion since 1967, the Palestinian village of al-‘Isawiyya, which had been enclosed within the Mount Scopus enclave since Jerusalem was divided in 1948, was completely besieged and has had its lands expropriated from all sides for the purpose of settlement expansion:

- To the west and northwest for the construction and expansion of the French Hill and Giv‘at Shapira settlements

- To the east for the construction and expansion of the Ma‘ale Adumim and Mishor Adumim settlements, as well as the future E-1 settlement (see Map 3, “E-1 Plan,” in Israel’s Vision of a Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem)

- To the north for the establishment of a bypass road that connects Ma‘ale Adumim with the French Hill settlement

- To the northeast for the purpose of establishing the Separation Wall

- To the northeast for the benefit of the Hebrew University and Hadassah Hospital

As a result, today, al-‘Isawiyya is completely surrounded by settlements and is left with 5 percent of its original lands. It also suffers from municipal neglect and an intense campaign of home demolitions. That is, the de facto de-enclavization of Mount Scopus ensured the reverse for al-‘Isawiyya—its ghettoization.32

To the north of the expanded municipal boundaries, settlements like Ramat Allon, Ramat Shlomo, Neve Ya’akov, Pisgat Ze’ev, and the Atarot industrial settlement besiege and limit the growth of the Palestinian Jerusalem communities of Beit Hanina and Shu‘fat. In addition, they sever the possibility of connection between Palestinian populated areas in Jerusalem and Ramallah.

The Atarot industrial park was built on lands confiscated from the Palestinian neighborhoods of Beit Hanina, al-Ram, and Dahiyat al-Barid33 in a location that lies between the Palestinian neighborhoods of Kufr ‘Aqab, Qalandiya, and al-Ram. When it was established in 1970, it fragmented a space of transit within the heart of Palestinian communities and obstructed Palestinians’ access to the Jerusalem International Airport, which Israel subsequently closed to civilian traffic in 2000.34

In 2021, Israel submitted a plan to expand the Atarot industrial park into a settlement neighborhood with 9,000 housing units. If approved, the plan would further erode territorial contiguity between Palestinian neighborhoods in the north of Jerusalem, which are already fragmented due to the Separation Wall surrounding Atarot. It would also further drive a geographic wedge between Palestinians in Ramallah and Jerusalem, historically interconnected cities (see The Separation Wall).35

To the south, settlements like Gilo and Har Homa fragment Palestinian localities that happen to fall inside the municipal boundaries from those left outside of them. Har Homa, for example, was built on the confiscated lands of Jabal Abu Ghuneim. “Har Homa” literally means “Wall Mountain,” which indicates the role of the settlement, serving as a barrier between Bethlehem and its northern environs, particularly the Palestinian village of Sur Bahir, to which it has been historically connected. Indeed, Palestinians submitted a petition to the Israeli High Court in 1994 opposing the expropriation of land for the establishment of Har Homa. They asserted that the settlement discriminated against the Palestinians, specifically those residing in Sur Bahir. The petition was rejected, and the settlement was built.36

In 2021, Israel declared its intentions to expand its newest settlement in East Jerusalem, Givat HaMatos, which was built in 2005 on the confiscated lands of Beit Safafa on the southern side of the city. Israel plans to build thousands of new units there and an infrastructure that links the expanding settlement of Har Homa to that of Gilo.37 While Israel has been facing international pressure not to expand this settlement, it has nonetheless advanced plans to do so.38 If built, the expanded settlement would seal the southern section of the Inner Ring, utterly disconnecting the historically linked Palestinian communities in the south of Jerusalem from those in Bethlehem.

2. The Outer Ring: Settlement belt around Jerusalem

The Outer Ring consists of state-authorized settlements and settlement outposts built on confiscated Palestinian land in areas of the occupied West Bank surrounding Jerusalem. There are three settlement blocs in this area:

- Gush Etzion to the south

- Ma‘ale Adumim to the east

- Giv‘at Ze’ev to the north

Together, they encompass and link more than 28 state-authorized settlements and about 16 settlement outposts that are connected to each other and to the city’s core through a network of Jewish-only bypass roads.

These settlements take the shape of “rural” and “suburban settlements,” effectively functioning as satellite settlements that offer subsidized housing for Israelis or Jewish settlers from abroad who want to live close to Jerusalem. The Outer Ring includes large residential settlements such as Ma‘ale Adumim and Giv‘at Ze’ev,39 which have also developed their own commercial centers, as well as a network of nonresidential settlements, such as tourist and industrial parks. These settlements also have their own networks of military checkpoints managed by the Israeli army and private agencies, and by their own administrative bodies, such as municipalities and local and regional councils that fall under the military administration of the district of “Judea and Samaria.” These include: Matei Binyamin regional council, Gush Etzion regional council, Ma'aleh Adumim municipal jurisdiction, and Giv'at Ze'ev local council.

Table 2: The Outer Ring of suburban and rural settlements

| Settlement name | Year of land expropriation and beginning of construction40 | Location in the ring in relation to the metropolitan center of Jerusalem | Settlement type41 | Palestinian localities dispossessed for settlement construction42 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kfar Etzion | 1967 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | – |

| Rosh Tzurim | 1969 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | Nahhalin, Khirbat Beit Zakariyya |

| Alon Shvut | 1970 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | Nahhalin, Beit Ummar |

| Har Gilo | 1972 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | Beit Jala, al-Walaja |

| Elazar | 1975 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | al-Khadir |

| Ma‘ale Adumim | 1975 | East settlement bloc, urban anchor43 | Suburban | al-‘Izariyya, Abu Dis, al-Tur, al-Khan al-Ahmar, al-‘Isawiyya, ‘Anata, Nabi Musa |

| Beit El | 1977 | Furthest north satellite | Suburban | Dura al-Qar‘, al-Bira, ‘Ayn Yabrud |

| Migdal Oz | 1977 | Furthest south satellite | Rural | – |

| Tekoa | 1977 | Southeast satellite | Rural | Tuqu‘ |

| Beit Horon | 1977 | North settlement bloc (Giv‘at Ze’ev) | Rural | Beituniya, al-Tira, Beit ‘Ur al-Fawqa, Khirbat al-Misbah |

| Kfar Adumim | 1979 | East settlement bloc (Ma‘ale Adumim) | Rural | ‘Anata, Hizma, al-Khan al-Ahmar |

| Efrat | 1980 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | al-Khadir, Artas, Wadi al-Nas, Khirbat Beit Zakariyya |

| Psagot | 1981 | Northeast satellite | Rural | al-Bira |

| Ma‘ale Mikhmas | 1981 | Northeast satellite | Rural | Deir Dibwan, Burqa |

| Ma‘ale Amos | 1981 | Furthest southeast satellite | Rural | Kisan |

| Neve Daniel | 1982 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | Wadi al-Nas, al-Khadir |

| Nokdim | 1982 | Southeast satellite | Rural | Tuqu‘, Jubbat al-Dib |

| Almon | 1982 | East settlement bloc (Ma‘ale Adumim) | Rural | ‘Anata, al-Khan al-Ahmar |

| Giv‘at Ze’ev (+ Giv’on HaHadasha) | 1983 | North settlement bloc, urban anchor | Suburban | Beit Ijza, Biddu, al-Jib, Beit Duqqu, Beituniya |

| Geva Binyamin (Adam) | 1984 | Northeast satellite | Rural | Jaba‘ |

| Gevaot | 1984 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Outpost | Nahhalin |

| Kedar | 1985 | East settlement bloc (Ma‘ale Adumim) | Rural | al-Sawahira al-Sharqiyya |

| Kokhav Ya’akov | 1985 | Northeast satellite | Rural | Kufr ‘Aqab, Burqa |

| Beitar Illit | 1985 | South settlement bloc, urban anchor | Suburban | Husan, Nahhalin |

| Har Adar | 1986 | Furthest northwest satellite | Rural | Beir Surik, Biddu, Qatanna |

| Bat Ayin | 1989 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Rural | Nahhalin, Khirbat Beit Zakariyya |

| Alon | 1990 | East settlement bloc (Ma‘ale Adumim) | Outpost | ‘Anata, Hizma, al-Khan al-Ahmar |

| Nofei Prat | 1992 | East settlement bloc (Ma‘ale Adumim) | Outpost | ‘Anata, Hizma, al-Khan al-Ahmar |

| Givat Hadagan | 1995 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Outpost | al-Khadir, Artas, Wadi al-Nas, Khirbat Beit Zakariyya |

| Mishor Adumim | 1998 | East settlement bloc (Ma‘ale Adumim) | Industrial | ‘Anata, Hizma, al-Khan al-Ahmar |

| Givat Hahish | 1998 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Outpost | Nahhalin, Beit Ummar |

| Sde Bar | 1998 | Southeast satellite | Outpost | Tuqu‘, Jubbat al-Dib |

| Neve Erez | 2001 | Northeast satellite | Outpost | Deir Dibwan, Burqa |

| Har Shmuel | – | North settlement bloc (Giv‘at Ze’ev) | Touristic and residential | al-Nabi Samwil |

| Givat Hatamar | 2001 | South settlement bloc (Gush Etzion) | Outpost | al-Khadir, Artas, Wadi al-Nas, Khirbat Beit Zakariyya |

| Migron | 2002 | Northeast satellite | Outpost | Burqa, Deir Dibwan |

| Ma‘ale Rehavam | 2002 | Southeast satellite | Outpost | Tuqu‘, Jubbat al-Dib |

| Ibei HaNahal | 2002 | Furthest southeast satellite | Outpost | Kisan |

| Bnei Adam | 2004 | Northeast satellite | Outpost | Jaba‘ |

| Mitzpe Yeriho | – | Furthest east satellite44 | Outpost | Nabi Musa |

Note: This list does not include nonresidential Israeli settlements, touristic settlements, national parks, nature preserves, settlement planning zones, and other nonresidential areas that the Israeli military controls, all of which contribute to making up the network of the ring

Ma‘ale Adumim

Standing at its core, Ma‘ale Adumim was the first major “suburban settlement” to be established in the Outer Ring. First approved in November 1975, its location was chosen based on its strategic military function: overlooking Road 1, it stands between Jerusalem and Jericho at the center of the West Bank, providing Israel control over the main routes that connect Palestinian localities in Jericho (in the Jordan Valley) to Jerusalem.45 In addition, it was established at the narrowest width of the West Bank, positioning it to bifurcate the West Bank into a northern and a southern half if it continues to expand, thus blocking the emergence of any future Palestinian entity in the West Bank.

Ma‘ale Adumim was officially recognized as its own city in 1991. With its expanding boundaries, Palestinian communities belonging to the Jahalin and Sawahreh Bedouin tribes were displaced over the years, though they had lived on these lands for decades since Israel expelled them from their ancestral lands in the Negev desert during the 1948 War.46 The Israeli army carried out demolition orders in those communities as early as the 1980s, then again in the 1990s when members of the communities were expelled and relocated to a site near the Jerusalem municipal garbage dump, which is located on land belonging to the Palestinian village of Abu Dis, though Israel declared it as state land.47 To this day, more than 18 Palestinian Bedouin communities live in Area C east of Jerusalem, and they are constantly threatened by expansion of the Ma‘ale Adumim settlement bloc.48

For example, in 2018, Israeli authorities bulldozed the Palestinian Bedouin community of Khan al-Ahmar in order to expand settlements.49 And while these “suburban settlements” feature public parks, industrial zones, and pools, Palestinians in villages in the vicinity are denied permits for almost all residential and commercial construction. For instance, Palestinian Bedouin in the village of Abu Nawwar in al-‘Izariyya, which is next to the Kfar Adumim settlement, were denied a permit to build a small school.50 The army even dismantled a small prefab school built with French funding and forced the children to attend classes outside in all weather conditions.

As part of its settlement expansion, Israel has planned to develop a large commercial and industrial zone in the E1 Corridor, directly east of Jerusalem, with a new neighborhood called Mevasseret Adumim—an airport, hotels, tourist destinations, roads, and a district police station built on 180 dunums of Palestinian-owned lands. The E1 Development Plan, which was initiated in the 1990s and awaits approval, places thousands of housing units in an area that comprises the last open space available to Palestinians in towns such as al-‘Izariyya and Abu Dis, whose residents own a significant part of the land in the area. If the expansion plan is approved, it will complete the merging of a Jewish “Greater Jerusalem” from West Jerusalem to Jericho, while severing the southern part of the Palestinian West Bank from its northern part. It will block the roads between Ramallah and Bethlehem, making it impossible for Palestinians to travel from the north to the south of the West Bank and vice versa (see The Separation Wall). Ultimately, it will bifurcate the West Bank, making a contiguous future Palestinian state impossible.51

Beitar Illit and Giv‘at Ze’ev

Much like how Ma‘ale Adumim serves as the core center of the eastern settlement bloc of Jerusalem, Beitar Illit to the south and Giv‘at Ze’ev to the north act in the same manner. In effect, the settlements to the north, east, and south of Jerusalem and their expanding bypass roads and security infrastructure will ultimately bifurcate the Palestinian-populated areas of the West Bank.52 Moreover, the route of the Separation Wall contributes to realizing this vision of a Jewish “Greater Jerusalem”; that is, while it traps and isolates Palestinian neighborhoods and localities around Jerusalem, it simultaneously envelops and folds into the city the major Jewish settlement blocs of Gush Etzion, Giv‘at Ze’ev, and Ma‘ale Adumim. As a result, the wall and its network of fences leave thousands of Palestinians trapped in ghettoized communities that are forcibly disconnected from the surrounding areas, such as Kufr ‘Aqab and Shu‘fat refugee camp. Indeed, government proposals have been put on the Knesset table multiple times that aim to incorporate the Israeli settlement blocs into the municipality while demoting the status of the Arab neighborhoods outside the wall (see Israel’s Vision of a Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem).

Satellite settlements

In addition to the interconnected settlement blocs around Jerusalem, the Outer Ring also includes satellite settlements at a distance from the metropolitan core that are connected to it with Jewish-only bypass roads. Road 60 connects the settlements northeast of Ramallah (the so-called fourth settlement bloc) made up of the settlements of Beit El, Psagot, and Kochav Ya’akov, to the core of Jerusalem.53 To the south of Jerusalem, the Gush Etzion settlement and settlements north of Hebron, such as Efrat, built on Palestinian land, are also connected through an underground tunnel road, as well as to Road 60, which dissects Palestinian localities in the Bethlehem region from one another.

Southern settlements

South of Jerusalem, the Separation Wall enfolds the settlement of Har Gilo, which is outside the municipal boundaries, into Jerusalem while simultaneously completely encircling the ancient Palestinian village of al-Walaja. New plans there also include the building of the Giv‘at Yael settlement, as well as a new section of the Har Gilo settlement (Har Gilo West), announced in 2020. All of these plans include the confiscation of Palestinian lands south of Jerusalem, including al-Walaja; the approval and construction of these plans will amount to the absolute suffocation if not outright obliteration of the village. These settlements will also be connected by the Refaim Stream National Park, opened in 2018 for the sole enjoyment of Israelis, while the neighboring Palestinian villagers who own the land are shut out of it by a strategically placed checkpoint.

Also in the south is the illegal settlement of Har Homa (Hebrew for “Wall Mountain”; in Arabic, the name of the mountain is Jabal Abu Ghneim). Har Homa, approved for initial development in 1997 after a series of land confiscations in the early 1990s, created a deliberate territorial wedge between the Palestinian-populated areas of Sur Bahir and Umm Tuba inside the municipal boundaries and the cities of Bethlehem, Beit Jala, and Beit Sahur in the West back, just south of the city boundary, thereby closing a perceived “hole” through which Palestinians could prevent the encirclement of Jerusalem by Jewish populated areas.

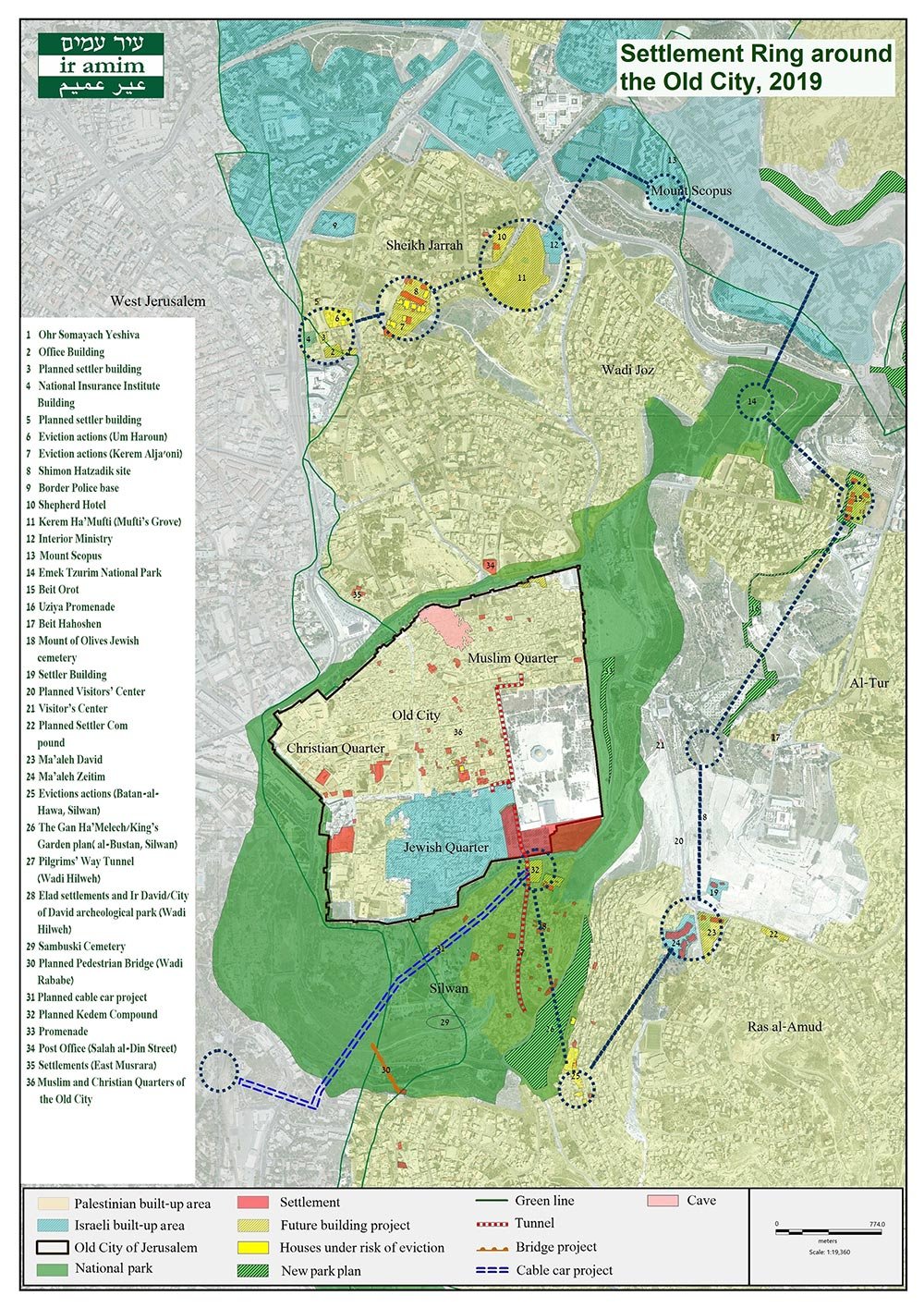

3. The Core Ring: Settlement belt within Palestinian neighborhoods in and around the Old City

The Core Ring comprises Jewish settlement outposts inside the Old City and directly surrounding it from the north, east, and south in Palestinian neighborhoods such as Silwan, al-Tur, Sheikh Jarrah, and Wadi al-Joz. In addition to many settlement enclaves, there are nine settlement outposts in Palestinian neighborhoods around the Old City. In the process, thousands of Palestinian family homes in the heart of Jerusalem have been taken by settlers, with over 5,19254 apartments in the Old City alone—excluding the Jewish Quarter (see Forcible Home Expulsions). In and around the Old City, these settlements occupy points “along a ring of tightening Israeli control,”55 centered around the Jewish Quarter. These relatively small settlement compounds form a continuous ring of settler-controlled areas that produce an interconnected Jewish “bubble” within Arab homes, neighborhoods, and villages.56 This “bubble” comes with armed guards and an expanding network of surveillance technology, including cameras with face recognition software.

Table 3: The Core Ring of settlement neighborhoods

| Settlement name | Year established | Location in the ring in relation to the Old City | Settlement type and management | Palestinian neighborhood in which outpost is inserted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The City of David | 1991 | South | Touristic archaeological settlement managed by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority and operated by the El-Ad private settler organization. | Silwan—Wadi Hilweh |

| Yemenite neighborhood | 2004 | South | Settlement enclave managed by Ateret Cohanim | Silwan—Batn al-Hawa |

| Beit Orot | 1991 | Northeast | Settlement compound managed by El-Ad | al-Tur |

| Ma‘ale HaZeitim | 2003 | Southeast | Settlement compound | Ras al-Amud |

| Shimon HaTzadik | 2001 | Center North |

Settlement Compound managed by Nahalat Shimon settler organization | Sheikh Jarrah |

| Bnei Zion | 2014 | Center North |

Settlement compound managed by Ateret Cohanim | Musrara |

| Nof Zion | – | Far Southeast (outside the Holy Basin) | – | Jabal Mukkabir |

Core Ring settlements can be individual settlements, comprising as few as one settler within a Palestinian home (or even one room), such as settlers living in Palestinian homes within the Muslim Quarter of the Old City. They can also take the form of settlement enclaves, which are usually composed of adjacent Palestinian homes taken over by settlers that are expanded upon and connected to one another, forming apartment complexes or compounds. In addition, they can take the form of tourist settlements and national parks administered by settler organizations which manage public, touristic, archaeological, and educational resources, programs, and events that promote religious-Zionist narratives about the history of the city, often on the ruins of displaced Palestinian homes and neighborhoods from which the original residents themselves have been displaced and banned. These tourist settlements attract tens of thousands of tourists from within the country and abroad, enriching the settler movements and expanding their activities in Jerusalem.57 The City of David in Silwan is a prominent example.

These settlements are managed by private settler organizations that are internationally funded, especially by donors in the United States.58 Extremist settlers driven by a messianic ideal to Judaize the city inhabit these settlements, and they are often supported by multiple state, municipal, and sub-municipal officials and agencies, including different ministries and police forces. Indeed, the Israeli state provides these settlers with 24-hour private security guards funded by the Ministry of Housing.

In those core areas of East Jerusalem, Israel has confiscated Palestinian lands in order to build 13 tourist sites, in addition to 30 more across the West Bank, to highlight the Jewish history of the area59 (see Forcible Home Expulsions).

To expedite the establishment of settlement outposts, the municipality has lifted all obstacles in the face of settler organizations to be granted building permits, while Palestinians in the same neighborhood might wait 16 years.60 In addition, Israel provides exclusive services to the Jewish settlements, including public playgrounds and other infrastructure. Moreover, while Palestinians in these neighborhoods suffer from an 80 percent poverty rate, and they pay three times more taxes than settlers living in private settlements in their own neighborhoods.61

Adding to this heavy economic toll, with an institutional bias in favor of well-funded settler organizations that are knowledgeable about the legal system and directly connected to legal authorities, impoverished Palestinian families who want to protect their homes from expropriation are often forced to engage in protracted legal battles that add to the hefty financial strains they already endure and more often than not are unsuccessful.

Israeli guards posted at these settlements often “employ physical and verbal violence and abuse Palestinian residents”62 in the name of protecting Jewish residents, and in spite of the fact that extremist settlers usually instigate the violence, including vandalizing Palestinian property, physically assaulting Palestinians, or attacking them with weapons.63 While settlers are heavily protected by the police, who routinely detain and arrest Palestinians if settlers complain, Palestinians are left with no protection from the settlers. Indeed, complaints by Palestinians of violent settlers are rarely addressed and are given tacit consent by the police.64

Categories of Core Ring settlements

Individual settlements in the Old City: These settlements are connected by pathways meant to gradually build up an exclusively Jewish infrastructure linking the Jewish Quarter to its surrounding satellite settlements, thus naturalizing the connection of the Core Ring of settlements to Israeli-controlled West Jerusalem. Initially led by a few ultra-orthodox settler groups such as the Young Israel Movement, which was formed by former Gush Emunim members, the movement to settle the Old City first targeted the Muslim Quarter. It was a gradual yet effective process which by the early 1980s had established several settlement enclaves inside the Old City.65 Over the years, settlement activity expanded exponentially in the Old City whereby “the Israeli authorities spread their grip to al-Wad Road that runs parallel to the Haram [al-Sharif’s] western wall.”66

Settlement compounds surrounding the Old City: In 2021, the Custodian of Absentee Property started “promoting widespread plans” for building settlements and housing complexes near Palestinian neighborhoods around the Old City. Two would be built to the north of the Old City in Sheikh Jarrah and near Damascus Gate (in addition to a third in the norther Palestinian neighborhood of Beit Hanina, and another three near the southern Palestinian neighborhoods of Beit Safafa and Sur Bahir). These settlements would confine the open spaces of these Palestinian localities and limit the possibility of their future natural growth. In addition, building these settlements would lead to the expulsion of Palestinian residents and to tightening the settlement ring around the city.67 Furthermore, ongoing settlement plans by the Jerusalem municipality and settler organizations in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan threaten to demolish Palestinian homes and structures, and to expel their Palestinian residents.68 Indeed, as of 2019, 175 Palestinian families are under threat of expulsion69 (see Forcible Home Expulsions).

Finally, these settlements would lie in proximity to the Green Line, indicating that their establishment is part of a larger long-term plan that aims at consolidating the Core Ring and entrenching its connection to the rest of Israeli Jerusalem. In the end, these “facts on the ground” would erode the line separating between “West” and “East”' Jerusalem, solidifying de facto Israeli Jewish control over all of Jerusalem.

Contributors

Researcher and Writer: Amir Marshi, Jerusalem Story

Editor: Nadim Bawalsa, Jerusalem Story

Research Assistant: Hassan Doostdar, Jerusalem Story

Notes

The term settlement was also used to refer to Israeli settlements in the Sinai Peninsula until 1982, and Gaza until 2005.

See Allegra Pacheco, “The Legality of Settlements,” in Meir Margalit, Seizing Control of Space in East Jerusalem (Tel Aviv: Sifrei Aliat Gag, 2010), 13–15; “The Tourism Industry of the Settlements,” Amnesty International, 2019; Maha Abdallah, “Atarot Settlement: The Industrial Key in Israel’s Plan to Permanently Erase Palestine,” al-Haq, 2019; and Ir Amim, “Settlements and National Parks.”

“Israel Launches New Settlement Plans,” Asharq al-Awsat, January 9, 2022.

Nur Arafeh, Samia al-Botmeh, and Leila Farsakh, “How Israeli Settlements Stifle Palestine’s Economy,” al-Shabaka, December 15, 2015.

“Economic and Social Consequences of Israeli Settlements—SecGen Report—Question of Palestine,” United Nations, July 7, 1992.

B’Tselem, cited in John Murphy, “A City Divided,” The Baltimore Sun, January 2, 2007.

“Data on Demolition and Displacement in the West Bank,” OCHA, February 15, 2022.

Nisreen Alyan, Mahmoud Qarae’en, Keren Tzafrir, Miri Gross, and Tali Nir, “Unsafe Space: The Israeli Authorities’ Failure to Protect Human Rights amid Settlements in East Jerusalem,” Association for Civil Rights in Israel, September 2010.

Numbers are based on a cross-check calculation using the following sources: Mohammed Haddad, “Mapping Israeli Occupation,” Al Jazeera, May 18, 2021; Charlie Hoyle, “Interactive Timeline: The History of Israeli Settlements since 1967,” The New Arab, November 20, 2019; “Jerusalem,” Peace Now; “Settlements,” B’Tselem, January 16, 2019.

“Israeli Settlements in the West Bank: Annual Statistical Report, 2020” [in Arabic], Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, November 2021.

TBD

Based on data from the Jerusalem Story cartography team.

According to 2017 data, if we supplant the number of settlers in municipal Jerusalem (209,270) only with the three of the surrounding settlements of Beitar Illit (54,557), Ma‘ale Adumim (37,817), and Giv‘at Ze’ev (17,323), we get 318,967, which is already more than half of West Bank settlers, the grand total of which in 2017 was 588,496. And this is without including the various other settlements and outposts in the region. See “Statistics on Settlements and Settler Population,” B’Tselem, January 16, 2019.

Hoyle, “Interactive Timeline.”

Jeff Halper, “Dismantling the Matrix of Control,” MERIP, September 11, 2009.

Ibrahim Matar, “Israeli Settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip,” Journal of Palestine Studies 11, no. 1 (1981): 93–94.

Salem Thawaba and Hussein al-Rimmawi, “Spatial Transformation of Jerusalem,” Journal of Planning History 12, no. 1 (2012): 70.

“Israeli Settlements and International Law,” Amnesty International, 2019.

“Applying for a Building Permit in East Jerusalem,” Norwegian Refugee Council, February 15, 2017.

Zena al-Tahhan, “Jerusalem: Israel Forces Palestinians to Self-demolish Own Home,” Al Jazeera, January 31, 2022.

“Data on Demolition.”

“The Occupation of Water,” Amnesty International, November 29, 2017.

Violet Qumsieh, “The Environmental Impact of Jewish Settlements in the West Bank,” Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture 5, no. 1 (1998).

All settlements in the Inner Ring fall under expanded Israeli municipal jurisdiction and are planned and maintained by the Israeli Municipality.

It was emptied in 1968.

The Mount Scopus enclave was controlled by Israel before 1967, and it includes the Hebrew University, established in 1925, Hadassah Hospital, established in 1918, and the French Hill settlement, which has extended beyond the Green Line and into the “hinge” neighborhoods that are supposed to connect the Mount Scopus enclave to West Jerusalem.

“Hinge” neighborhoods refer to settlements built between the Mount Scopus enclave and West Jerusalem, hence integrating the enclave and blurring the Green Line.

Yfaat Weiss, “Sovereignty and the Mount Scopus Enclave in Jerusalem,” Law Log, March 2016.

“Al Isawiyeh: From a Rich Village to Landless Village,” POICA, December 27, 2005, .

Abdallah, “Atarot Settlement.”

Abdallah, “Atarot Settlement.”

Office of the European Union Representative, “2021 Report on Israeli Settlements in the Occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem,” European Union, July 20, 2022.

“Land Grab: Israel’s Settlement Policy in the West Bank,” B’Tselem, May 2002.

“Israel Launches New Settlement Plans,” Asharq al-Awsat, January 9, 2022.

Abdelraouf Arna‘out, “Israel to Expand Settlement That Will Cut Off Jerusalem from Bethlehem,” Anadolu Agency, October 13, 2021.

Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (London: Verso Books, 2017), 122–25.

From OCHA and B'Tselem, “Settlements population, XLS.”

Settlements in the Outer Ring fall under various Israeli jurisdictions administered by the Civil Administration such as Mateh Binyamin Regional Council.

Based on ARIJ profile studies of the mentioned villages and “Colonization and Wall Resistance Commission, Israeli Colonies in the West Bank 1997–2018,” Palestinian Liberation Organization, 2019. For Migron, see “The Migron Petition,” Peace Now, October 2006. For Nikodim, see Anne-Marie O’Connor, “20 Minutes from Modern Jerusalem, a Palestinian Village Is Stranded in the Past,” Washington Post, October 22, 2016. For Ma‘ale Amos, see “Israel Levels Land in Palestinian Village to Expand Illegal Settlement,” February 7, 2022, Middle East Monitor.

An urban anchor settlement functions as a center in the settlement blocs that form the Outer Ring.

Satellite settlements are clusters of usually small settlements spread in between the settlement blocs but are connected to the metropolitan core by bypass roads.

Weizman, Hollow Land, 112.

“Ma’ale Adumim Area,” B’Tselem, May 18, 2014.

“Ma’ale Adumim Area.”

“Tightening of Coercive Environment on Bedouin Communities around Ma’ale Adumim Settlement,” OCHA, March 11, 2017.

David Shulman, “The Bedouins of al-Khan al-Ahmar Halt the Bulldozers of Israel,” The New York Review, October 26, 2018.

“Israeli Settlements and the Encirclement of East Jerusalem,” France 24, November 26, 2018.

Office of the European Union Representative, “2021 Report on Israeli Settlements.”

“Displaced in Their Own City: The Impact of Israeli Policy in East Jerusalem on the Palestinian Neighborhoods of the City beyond the Separation Barrier,” Ir Amim, 2015. See also Eyal Hareuveni, “Arrested Development: The Long-Term Impact of Israel’s Separation Barrier in the West Bank,” B’Tselem, October 2012.

Based on data collected by the Jerusalem Story cartography team.

“Israel Seeking to Establish 50km Settlement Belt in Jerusalem,” International Middle East Media Center, November 23, 2018.

Nir Hasson, “Jerusalem Plans Promenade Connecting Settler Homes in Palestinian Neighborhood,” Haaretz, February 8, 2018.

This list only includes those settlement outposts which were established by settler organizations and the municipality and form a considerable compound. It does not include many of the individual settlements (e.g., homes taken over in the Old City [see Forcible Home Expulsions]) or small settlement compounds spread across Palestinian neighborhoods (e.g., East Musrara or Beit Hahoshen) or those with planned expansions (e.g., Kedem Compound) or nonresidential areas that Israel controls (e.g., Emek Tzurim National Park).

Information (except for Nof Zion, about which little is known).obtained from Ir Amim, “Tightening the Ring of Israeli Settlement around the Old City of Jerusalem Map Notes” December 2018.

Hasson, “Jerusalem Plans Promenade.”

Uri Blau, “From N.Y.C. to the West Bank: Following the Money Trail That Supports Israeli Settlements,” Haaretz, December 7, 2015.

“Tourism Industry of the Settlements.”

“Israel Seeking to Establish 50km Settlement Belt in Jerusalem.”

“Israel Seeking to Establish 50km Settlement Belt in Jerusalem.”

Alyan et al., “Unsafe Space.”

Reference

Alyan et al., “Unsafe Space.”

Geoffrey Aronson, “Settlement Monitor,” Journal of Palestine Studies 28 no. 4 (1999): 179.

Nazmi Ju’beh, “Jewish Settlement in the Old City of Jerusalem after 1967,” Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture 8, no. 1 (2001).

Nir Hasson, “Israel Advances New Projects for Jews across East Jerusalem That Would Push Palestinians Out,” Haaretz, December 13, 2021.

“The Case of Sheikh Jarrah,” OCHA, October 2010.

See “Systematic Dispossession of Palestinian Neighborhoods in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan,” Peace Now, 2019.