Due to the prominence of these families, Sheikh Jarrah was variously referred to at the time as the “al-Husseini Quarter” and the “al-Nashashibi Quarter.” It was also sometimes called the “Consuls Quarter,” because of the concentration of foreign consulates in this particular neighborhood.8 Among these were the Saudi Arabian, Egyptian, Iraqi, Lebanese, and Syrian consulates.9 Western consulates were located here as well.

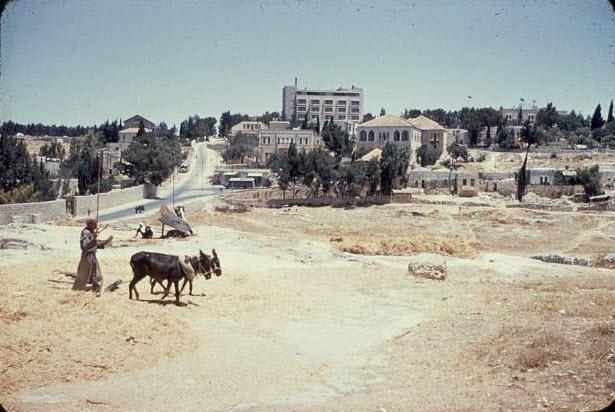

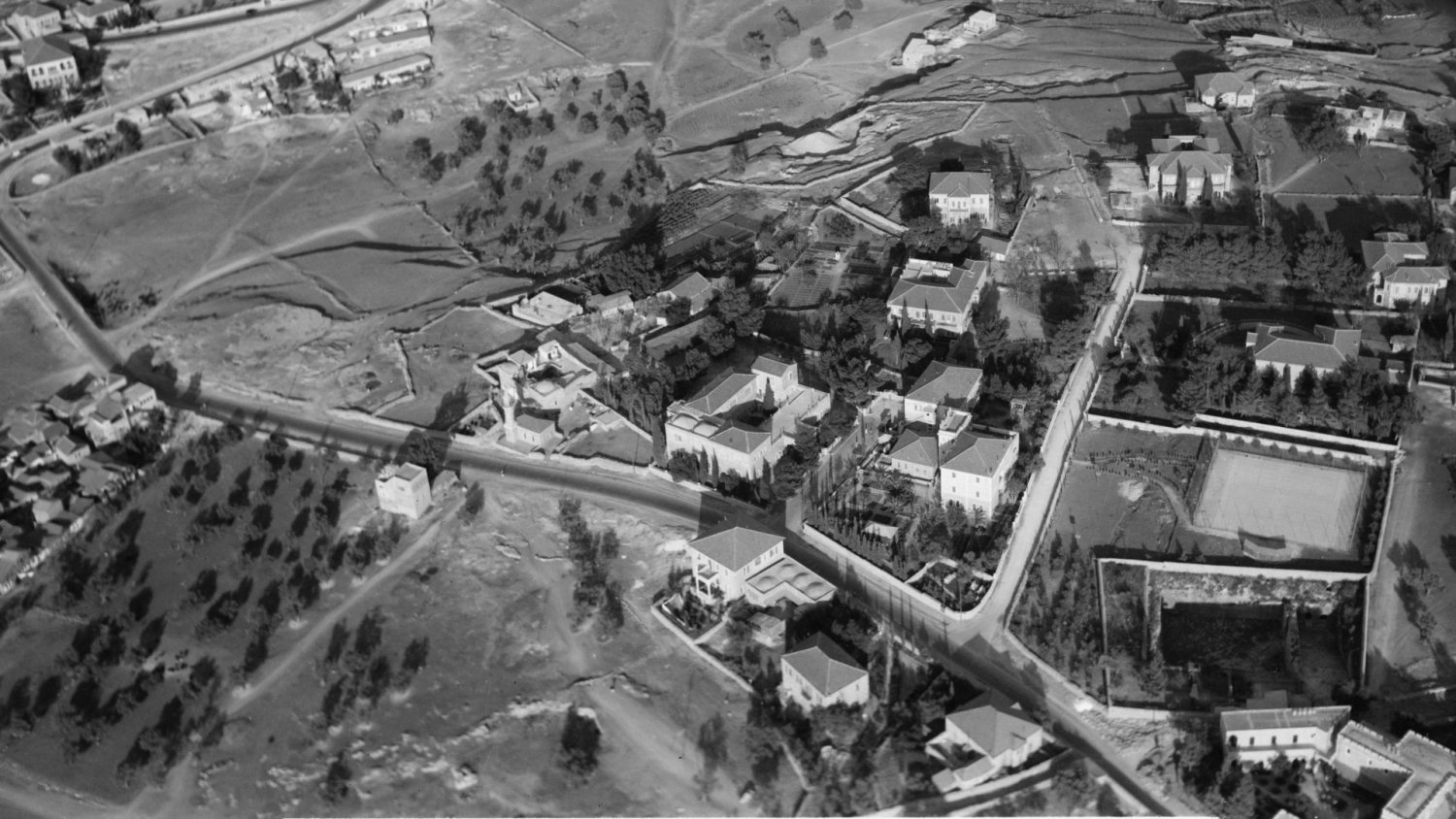

From the mid-20th century through the Mandate period, other Palestinian families began settling in Sheikh Jarrah, including the Jarallah, al-Mughrabi, al-Imam, Ghosheh, Nusayba, Hindiyya, al-‘Afifi, al-‘Isa, al-‘Asali, Sharaf, and al-‘Arif families, among others.10 In 1895, a mosque was built to house the tomb of Sheikh Jarrah along Nablus Road, which runs through the neighborhood. And in 1898, the Anglican St. George’s School for boys, which became the most prestigious secondary school for Jerusalem’s elite, was built between St. George Street and Nablus Road, not far from the mosque.11 As a result, in the 1905 Ottoman census, Protestant Palestinians formed the largest proportion of Christians in the neighborhood, numbering six families;12 the majority of Jerusalem’s Christians were settling further west of the city center in the new neighborhoods of Talbiyya, Qatamon, and al-Baq‘a, among others (see The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before “East” and “West”).

The census registered 97 Jewish families who resided in the Shim’on HaTzadik and Nahalat Shim’on communities adjacent to Sheikh Jarrah. Shim’on HaTzadik was established in 1890, followed by Nahalat Shim’on in 1891, on lands that had been purchased from the Ottomans by the Sephardic Community Council and the Ashkenazi General Council of the Congregation of Israel in 1876, to house mostly poorer Yemeni and Sephardi Jewish immigrants to Palestine.13

Muslim Palestinians historically outnumbered both Jews and Christians in Sheikh Jarrah. With 167 families registered in the Ottoman census of 1905 (roughly 1,250 people), the Muslims of Sheikh Jarrah were diverse, including wealthy former residents of Jerusalem’s Old City, Palestinians from other city centers in Palestine, including al-Khalil and Nablus, and Syrians from other parts of the region such as Damascus and Beirut.14

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and in April in particular, Sheikh Jarrah was a focal point for violent clashes and attacks by Haganah and Arab forces.15 Due to its strategic location immediately north of the city center, it was prized as a gateway into the Old City. Indeed, as tensions escalated in Jerusalem in April, Jews were concerned about losing Sheikh Jarrah. On April 25, at which point the British had driven the Haganah out of the neighborhood, Harry Levin, a Jewish resident of Jerusalem, wrote in his diary: “The Jews are fuming. Sheikh Jarrah is one of the strategic key-points of the city. Through it Arab bands have been pouring into Jerusalem without check.”16 Just days prior, on April 14, a convoy of medical cars and personnel en route to Hadassah Hospital (which was accessible only by a road to Mount Scopus that passed through Sheikh Jarrah), escorted by the Haganah, was ambushed by Arab forces in Sheikh Jarrah in a shooting standoff that resulted in the death of 79 Jews and 1 British soldier. According to eyewitnesses, the attackers were heard shouting “Minshan Deir Yasin!” (because of Deir Yasin), referring to the Palestinian village where Zionist paramilitary forces massacred 100 Palestinians five days earlier on April 9.17

Ultimately, the Haganah was not successful at taking Sheikh Jarrah, and Hadassah Hospital and the Hebrew University thus were left in an enclosed zone on the eastern side of Jerusalem for 19 years between 1948 and 1967.

At the war’s end, Sheikh Jarrah was cut off from what would become Jewish West Jerusalem and lay on the eastern edge of the no-man’s-land that ran along the 1949 Armistice (Green) Line. It fell in the part of Jerusalem that became East Jerusalem and was annexed by Jordan.

In 1956, the Jordanian government moved 28 Palestinian refugee families who had been displaced from their homes in Jaffa and Haifa during the 1948 War into Sheikh Jarrah. Despite agreements with UNRWA to resolve the refugee status of these Palestinian families following a three-year residence in the area, this never happened, and in the 1967 War, Israel occupied East Jerusalem, including Sheikh Jarrah, which remains the case to this day.18