Overview

Credit:

Jessica Buxbaum for Jerusalem Story

Land Registration in Jerusalem Is a “Grand Land Theft” from Palestinians—Ir Amim’s Amy Cohen

Snapshot

Jerusalem Story sat with Amy Cohen, international relations director of Jerusalem-focused nonprofit Ir Amim, to discuss her organization’s joint report with planning rights organization Bimkom entitled Grand Land Theft: Ramifications of Israel’s Registration of Land Ownership in East Jerusalem. The report analyzes Israel’s land ownership registration process in occupied East Jerusalem, known as “settlement of land title” (SOLT), and reveals the state’s true intentions behind undergoing the process. Rather than the purported goal of benefitting Palestinians economically, helping them register their properties to develop them, SOLT ultimately paves the way for Israel to confiscate more Palestinian lands and properties in order to solidify its grip over the city.

Ir Amim and Bimkom’s report The Grand Land Theft: Ramifications of Israel’s Registration of Land Ownership in East Jerusalem was released in June 2023 and includes five years (2018–23) of data collected by the organizations on the SOLT process. The Israeli government budgeted 50 million shekels (more than $13 million) in 2018 to renew the SOLT process as part of Government Decision 3790 to “reduce socioeconomic gaps and advance economic development in East Jerusalem.” The report details how the state is exploiting SOLT to advance illegal settlements and solidify Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem.

“The absence of registered land rights for Palestinians has been one of the primary obstacles to advancing formal urban development in East Jerusalem,” Ir Amim wrote in their email alert announcing the report’s release.1 “Although the SOLT process was depicted as a measure to rectify this situation, it rather serves as a guise under which Israel is seizing more land in East Jerusalem for Jewish settlement, while curtailing any possible establishment of Palestinian rights to their lands.”

Jerusalem Story sat down with Amy Cohen to learn about the report’s findings and SOLT’s ramifications for Palestinian Jerusalemites.

Jerusalem Story: What is Ir Amim’s report on the Grand Land Theft about?

Amy Cohen: It’s important to note that it’s a joint report with Bimkom, which is one of our partner organizations. Their focus is on the intersection of urban planning and human rights. So, with Bimkom, we’ve been tracking the process of settlement of land title, which is essentially the finality of land rights. In other words, it’s a process of land registration.

JS: Can you explain what land registration is, exactly?

AC: Land registration essentially enables an individual to establish the finality of rights to a particular plot of land, which is ownership. In order for there to be urban development or financial and economic development on a particular land or piece of property, you need the finality of rights to that particular piece of land. Land registration exists across the world in different countries, because it’s one of the foundations of urban and economic development—to establish who has possessory attachment to, or ownership of, the land in order to determine who can do what with it.

Briefly, once you can prove that you have ownership over a particular piece of land, you can more easily advance a zoning plan (in US English), or an outline plan (in British English). You then advance the outline plan for a particular plot of land or for a space, which then allows you to acquire building permits, for example.

This is what is happening in the context of East Jerusalem (see The Complex and Unresolved Status of Land in East Jerusalem). Without building permits, Palestinians can’t build homes or any structures on a particular piece of land. In addition to that, the registration of land really establishes who lays claim to it, who in the basic sense of the term has ownership of the land. In many ways, this comes to the heart of the conflict: who owns the land, lays claims to it, and who has the right to do so. It’s all about land (see An Expert Unravels the Complexities of Land Ownership in East Jerusalem).

So, we’ve been monitoring this process of land registration in East Jerusalem. We coined the term “Grand Land Theft” because Israel is using land registration to essentially steal, or confiscate, Palestinian land for the benefit of the state or settlers. It might seem like a bombastic or hyperbolic term, but it conveys the severity of the issue.

Because, in the past, the Israeli government used various measures to appropriate land in East Jerusalem. And for many years, between say after the occupation and the [1980] annexation—according to Israeli law annexation, in contravention to international law—they mainly concentrated on expropriation of land, most of it private Palestinian property across East Jerusalem, to build settlements.

But since the Oslo Accords were signed in the 1990s, expropriating large swaths of land for public purposes—similar to the concept of imminent domain in US English—became a lot more difficult for Israel to do due to international objection and scrutiny.

What our study concludes is that this land registration process is fulfilling the Israeli state’s goal of land expropriation but under the guise of benefitting Palestinians, helping them establish land rights to their lands so they can develop them. So, in lieu of expropriating the land, Israel ultimately appropriates it, if that makes sense, and it does it through a very bureaucratic process called land registration, or settlement of land title (SOLT), to avert international scrutiny.

JS: How did Ir Amim and Bimkom document this settlement of land title procedures? How was the study or the report executed?

AC: We’ve been tracking this since 2018. Ir Amim began with a long-term project monitoring a large Israeli government decision, known as Decision 3790, passed in 2018. It was a 2.1-billion-shekel investment in East Jerusalem. And it was, according to the Israeli government, designed for the socioeconomic development of East Jerusalem and in order to narrow socioeconomic gaps. It was unprecedented: it was the first time that the Israeli government admitted to some sort of neglect of East Jerusalem. Because again, even though according to our organization and the international community, it’s occupied territory under international law and Israel does not have sovereignty there, according to Israeli law, it is the sovereign. So, for Israel, East Jerusalem is under its administration and jurisdiction. In this way, Decision 3790 was really the first time that Israel was admitting, to some extent, to the neglect by agreeing to implement and to invest 2.1 billion shekels in East Jerusalem.

From the outset, Ir Amim—and of course, the Palestinian population and many other organizations that were following this government decision—knew that the impetus behind it was to increase Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem and to expand and entrench Israeli control over the city. There were various provisions within this decision, including different sectors they were investing in, such as education, roads, economic development and placement of women in the workforce, and so forth. But there were a few very, very alarming sectors, and one of them was this land registration process. Suddenly, after 51 years, Israel decided to resume the land registration process after it froze it in 1967 when it occupied East Jerusalem. Under Jordanian rule between 1948 and 1967, there was a land registration process that had begun, but it was very, very slow. What we found is that 90 percent of East Jerusalem’s lands were unregistered (see Land Settlement and Registration in East Jerusalem).

And so, for years, Israel froze this process for various reasons. They claimed it was political, too complex, and so on. Then, suddenly, in 2018, they revived it under the guise of benefiting the socioeconomic development of Palestinians in East Jerusalem.

We were immediately alarmed by this. There was great apprehension among our Palestinian partners that it would be used to appropriate more land, thereby dispossessing and displacing more Palestinians. So, for the last five years, we’ve been tracking this process, and what we’ve seen is that, first and foremost, the process is virtually devoid of all transparency according to protocol and regulations. There’s supposed to be a transparent process where Israel publishes where SOLT is taking place, how it’s being done, how many dunams of land are being part of the process, and so forth. And what we’ve seen is that the transparency is very, very limited to the point where we have essentially had to come up with our own system to monitor and track the progress with SOLT. We did this through scouring various government websites and mapping systems that they have online. And again, it’s not that it’s explicitly in front of us; we’ve had to put two and two together to figure out where SOLT is taking place.

So there’s basically in lieu of transparency, we’ve had to come up with our own system to kind of track it because it’s very convoluted. We have one particular individual who is the coordinator of this project and is tracking every single move.

And after years of tracking the process, in 2021, we really started to see movement on this issue. Over the past few years, SOLT has not—and this basically confirms our suspicions—is not being used for the benefit of Palestinians. We have not been able to find one block or plot of land being registered that is for the benefit of Palestinians—meaning that a Palestinian family has taken part in the process and that they are establishing rights to the land.

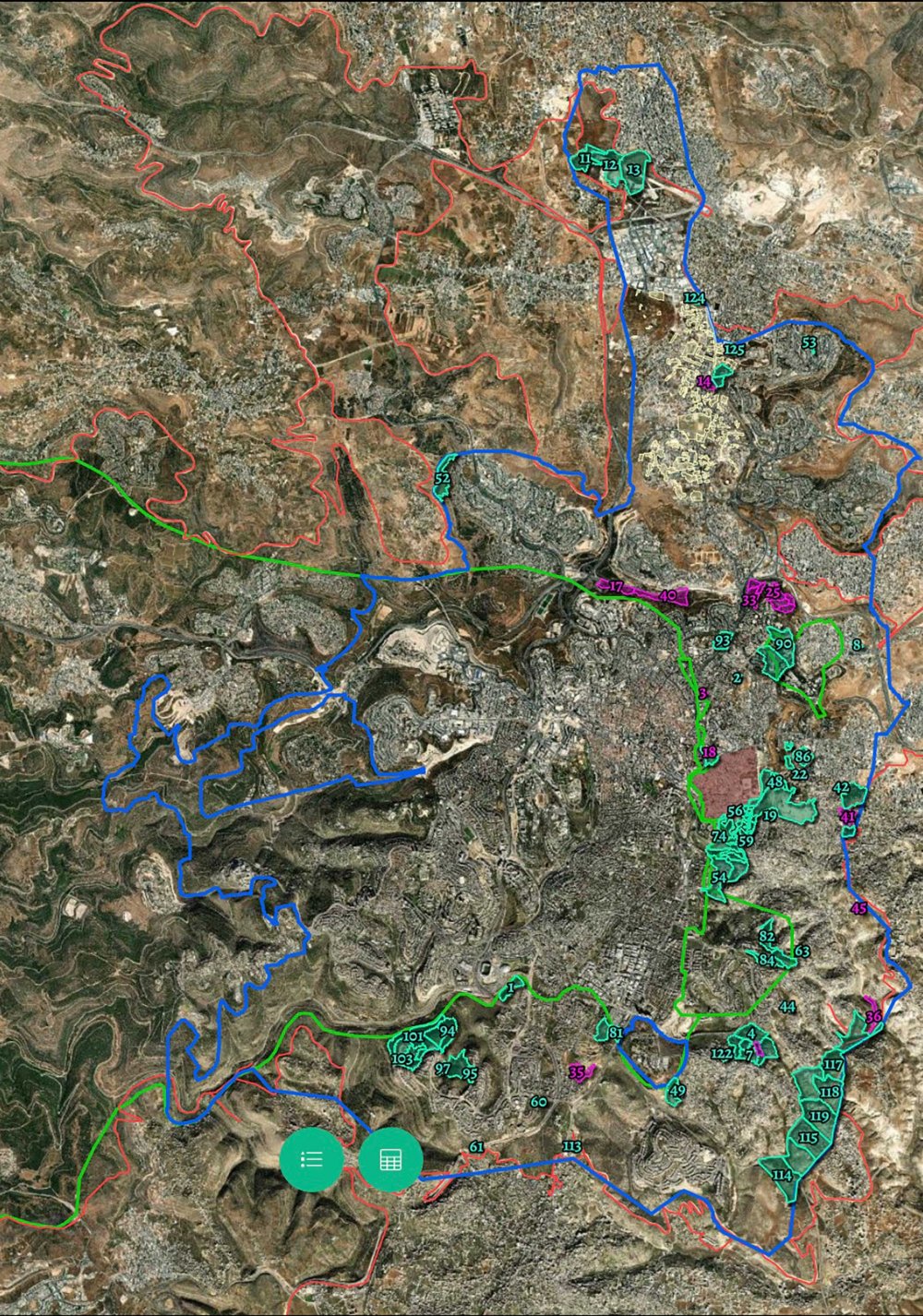

Until now, we’ve found that in around 90 percent of the land that we have monitored, the settlement of land title is taking place either for the benefit of the state or for settlers, which often intersect. For instance, the settlement of land title process is either taking place in areas where Israel is advancing new settlement plans like Givat Hamatos and Givat HaShaked, which surround Beit Safafa, and expanding the Ramot settlement. Another example is the area near Abu Dis, where they are advancing SOLT to expand Kidmat Tzion, a settler enclave. You also have the example of SOLT being undertaken in the Umm Haroun section of Sheikh Jarrah. And, of course, that’s where there’s eviction proceedings taking place against Palestinian families. Another area subjected to SOLT is Atarot, which is a major settlement on the northern perimeter of East Jerusalem for 9,000 housing units.

Essentially, SOLT is being used either to advance settlements, to register settler enclaves in the middle of Palestinian neighborhoods, or to enforce the absentees’ property law. Rather than outright confiscate and appropriate more land, say for settlements, we actually see settlement plans overlapping with SOLT in areas where the absentees’ property law supposedly applies, which would lead to the dispossession and displacement of Palestinians from their homes. There are a number of “enemy states” that were included in the 1950 absentees’ property law, and if a Palestinian individual was at any time present within one of these countries, they would be considered absentee. For example, Israel wants to build a settlement near Givat Hamatos on a land where a Palestinian woman lives. She is a dual US citizen and a Palestinian resident of East Jerusalem. But at one point, she or a member of her family was residing in Jordan, one of the “enemy states.” For Israel, this means that their land is considered absentee property.

It’s unbelievable. Before there was a peace agreement [between Israel and Jordan], this individual was in Jordan. According to the law, which of course is completely unjust and discriminatory, the property can be confiscated and put under the auspices of the Custodian of Absentee Property, who can then hand it over to an Israeli authority, like the Israeli Land Authority, for development into a settlement. It keeps passing through government bodies’ or settlers’ hands. And this is just one example of how the law is being used in conjunction with SOLT. And so, the fear here is that if they are to continue this process throughout East Jerusalem, which is their goal, you could have hundreds, if not thousands, of Palestinians under threat of dispossession through the application of the Absentees’ Property Law.

One of the reasons we are so concerned with this is because, lo and behold, the Custodian of Absentee Property is one of the state bodies intricately involved in SOLT, in the committee making decisions. So, the very mechanism and state body that has been involved in confiscation of Palestinian properties in the past and has worked very closely with settlers over the past three decades, sits on a committee tasked with facilitating the land registration process.

This leaves no doubt that the office of the Custodian of Absentee Property is going to be very, very closely involved in the process. And it has been.

The other issue in terms of potential displacement is the application of the 1970 law, which is the Legal and Administrative Matters Law that allows for Jews to reclaim pre-1948 assets in East Jerusalem—but then, of course, denying Palestinians the same right. To clarify, the General Custodian is the state body that is responsible for managing or overseeing assets that allegedly belonged to Jews prior to 1948, until they are “reclaimed.” What we’ve seen since 2021 is that the General Custodian has been intricately involved in SOLT.

SOLT is clearly being undertaken for the benefit of the state and settlers. In doing so, it’s adversely affecting Palestinians, creating this mass potential for their dispossession and displacement. This is essentially what we’ve done with the report, The Grand Land Theft; we tried to put it in lay terms, but we are talking about massive land seizure in East Jerusalem through a mechanism that is being touted as benefitting Palestinians.

JS: How did you find out that Israel started the land registration process if it wasn’t being announced or published?

AC: In terms of the land registration, the actual process itself was published and announced. It was part of Decision 3790. Where the transparency is lacking in how the process is taking place. For instance, we submitted a freedom of information request a year and a half ago for information on how they determine where to implement SOLT because it appeared to be very arbitrary. In other words, what’s not transparent is where exactly—and what are the parameters that determine where—they implement the process. We requested that they send us copies of the maps of where it’s being implemented and how it’s being implemented, and they denied this request saying that the maps are only there for the actual residents of the areas in which the process is taking place. But how does an individual know that the process is under way if they don’t have access to the maps? Their claim is that they go house by house in Palestinian areas announcing that the process is taking place or place leaflets and various announcements in the area. From our knowledge, and through our Palestinian partners, we have found that Palestinians affected by SOLT have not been privy to that information.

We also found out that while they do publish information on some of the blocks where the land registration process is taking place, they definitely don’t publish it on all of them. I’ll give you an example. We discovered back in 2021 that there was a pilot project for the land registration process taking place in Umm Haroun, in Sheikh Jarrah, but that information was not published anywhere, even though information on where they have started the process is supposed to be made public. Someone here [at Ir Amim] discovered it by chance by observing a change in numbering of the blocks in different maps online. So, we have to find ways of accessing this hidden information.

The caveat is that because of the lack of transparency, there is a big possibility that we have missed things and that there are more blocks that are undergoing the settlement of title process that we are not aware of. In the report, we do have a disclaimer indicating that this is the information and the data that we have been able to locate and that we have had access to, or gained access to, through the various mechanisms that we have created, but it’s definitely not complete.

JS: In the report, you explain that the lack of transparency is in violation of Israeli law. Can you take them to court over this?

AC: In theory, yes, we can. This has been something that Ir Amim and other partners, including Bimkom and several Palestinian organizations, have considered doing. The issue is that if we were to take them to court over transparency, it would somewhat legitimize the process. If we were to take them to court and they would admit that they failed in being transparent, they’ll simply say they’ll do better. But doing better is not going to help in the long-term, because they are using SOLT as a means to take over and seize more land and then dispossess Palestinians. So, even with more transparency, it’s not going to stop the end situation.

What’s ultimately happening is that Israel is determining the end game by finalizing land rights and who has ownership to land in one of the most contested pieces of real estate: Jerusalem. So, rather than tackle the transparency issue in court, which would legitimize the SOLT process, we are calling for it to be halted altogether. If we were in any other context, not defined by ongoing occupation, injustices, oppression, and deprivation of Palestinian rights, then yes, we would be advocates of a land registration process. And were there to be an independent Palestinian state, that Palestinian government would have to undertake that process in order to give Palestinians land rights to be able to develop the land. But in the current context of occupation, we are saying the whole process needs to be eliminated. The ramifications for Palestinians are too dire.

JS: Can you talk more about what those ramifications are?

AC: Geopolitically, the heart of the conflict is about who has titles to land, who is entitled to the land, and who has ownership of the land. And East Jerusalem is the epicenter of the conflict. If one would still embrace the two-state framework with two capitals in Jerusalem, Israel under this particular process is essentially determining the end game by appropriating more and more land, depleting more and more of the geographical space for any future Palestinian capital with a contiguous, territorial, and independent state.

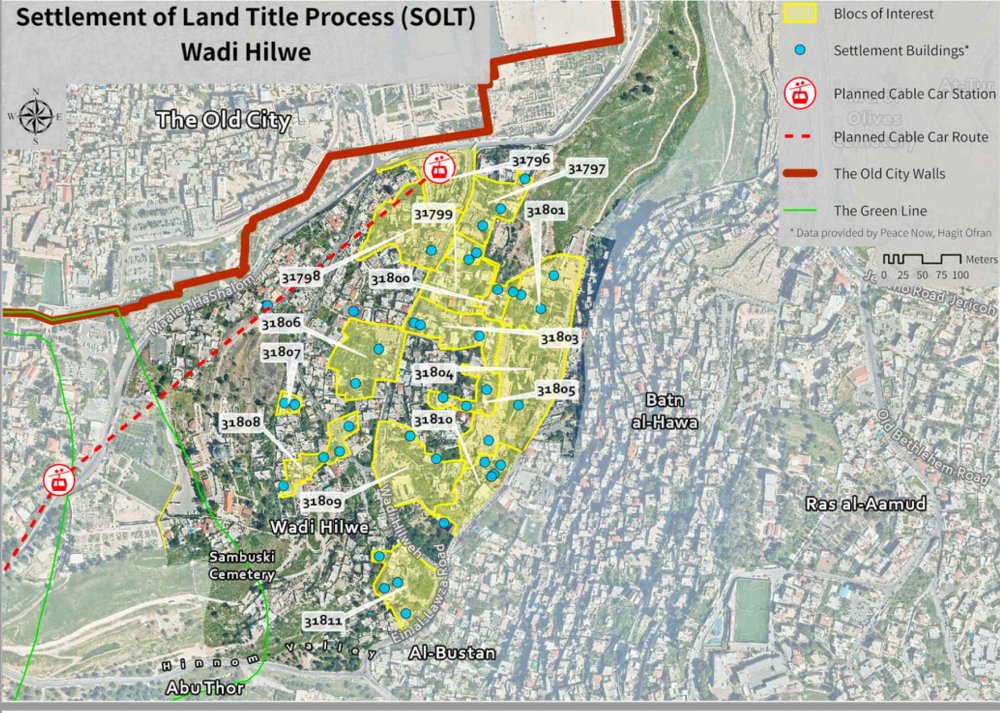

To give you an example, we started off the report with the example of Silwan, the Palestinian neighborhood just south of the Old City. It is one of the most politically sensitive areas in the conflict because of its religious and historical significance. But it’s a Palestinian neighborhood, and for many years, Jewish settlers and the Israeli state have targeted it for massive state and settler takeover. And in this very, very politically and religiously sensitive space, the settlement of land title has begun. Of course, it’s taking place in the areas where there are settler enclaves, compounds, or homes in the middle of Silwan. So, given this, were there to be a peace process, or some sort of negotiations, the two sides would have a very difficult time dividing Jerusalem, or coming to some sort of political resolution, because you have gone through the finality of land rights.

This doesn’t mean that one day SOLT won’t be contested, because it is in direct violation of international law. But dividing the city will be that much harder because SOLT finalizes land rights and gives those rights over to the state or to settlers. So, the issue of land ownership in Silwan, in the epicenter of the conflict in Jerusalem, shows that Jerusalem is no longer divisible in any sense. I’m not a proponent of dividing the city, but in terms of the two-state framework, SOLT has made it virtually impossible.

Beyond geopolitical implications, you also have the continued depletion of land for more and more Jewish settlements and construction, while at the same time depriving Palestinians of urban planning and housing rights, pushing them out of the city. In this sense, it’s about entrenching and consolidating Israeli control over the area.

As for the implications for Palestinian rights—for human rights—in terms of land rights and the ability to advance ownership claims of properties, SOLT makes it very difficult for Palestinians. Palestinians stand to be displaced from their homes or dispossessed from their lands because of the fact that the Israeli government can arbitrarily use the Absentees’ Property Law in registering lands. And this is another huge issue: most Palestinians are refusing to participate in SOLT, and with no claim to the land, the state reserves the right to confiscate it. Most refused because of apprehension that the property would be confiscated or because they don’t recognize Israel as the sovereign entity in East Jerusalem. So, they’re in this catch-22 situation where if they participate in the process, they run the risk of losing their land, but if they don’t participate in the process, they also run the risk of being displaced and dispossessed because, in either case, the state can appropriate and seize the land.

This is all in violation of international law, amounting to a form of forcible transfer. But it’s all covered by very bureaucratic language and terminology of settlement of land title and this kind of guise of being for the benefit of Palestinians. This makes it a lot harder to alert the international community and to raise the red flag, and this is a huge issue both in terms of human rights, and in terms of the end game of the conflict in Jerusalem.

That was our goal in the report—to not only present the international community with the hard data and empirical evidence, but to also break it down into terms so they can understand that this is not just some convoluted bureaucratic process of land registration. This is land theft.

JS: Why did Israel decide to renew the settlement of land titles?

AC: It’s a good question. We obviously have our speculations. As I mentioned before, they described it as a means to assist Palestinians in urban development and so forth. But the masterminds behind SOLT were Ayelet Shaked and Ze’ev Elkin. Ayelet Shaked was the minister of justice at the time, and Ze’ev Elkin was the minister of Jerusalem affairs. And while we don’t know this explicitly, given their records, it seems clear that SOLT was a means to help expand the settlement enterprise in East Jerusalem.

I think they saw it as an opportunity that was not being exploited or harnessed until the 2018 Decision 3790. And the reason why we attribute it to Ayelet Shaked is because she went on record at the time talking about this land registration process and that it was kind of her baby. And we know her political views and her support of the settler enterprise and so forth, so we see it as just another tool and another means of taking over more land in Jerusalem.

JS: The report mentions how 90 percent of the land in Wadi Hilweh in Silwan was targeted for SOLT. Why is the neighborhood such a significant target?

AC: Silwan has been targeted for years for the political and religious significance of its location—it’s where the City of David is located. And Wadi Hilweh is part of Silwan. All of the archaeological digs that are taking place there are run and operated by the Elad settler organization, and their activities have even expanded to the Hinnom [Wadi Rababa] Valley and elsewhere. They have an entire enterprise that they are running in very close coordination with the state. It’s very much within the same pattern as everything else we’ve seen: Wherever there are settler enclaves, Israel has plans to solidify control in those areas. Another one that I didn’t mention earlier is Nof Zion [in Jabal Mukabbir]. Nof Zion is a settler enclave. And right now as we speak, they’re advancing a plan to expand, and what do you know? SOLT is taking place on that exact plot of land.

So you see how there’s an overlap and it goes hand in hand and, and you can understand the kind of the goal and the objective behind it because it ultimately solidifies that control. Okay, you build a settlement here, you build a settlement there, and yes, it’s building on there, but this is kind of like the final stamp. It is nearly incontestable. So in Wadeh Hilweh, this is a place that has been long targeted by the state and by settlers for three decades now, and it’s only growing. So in order to finalize it and solidify it, you come in and you decide, okay, I’m going to draw up these blocks so that they include all of the settler enclaves and all of the compounds, as well as all the archaeological sites that are being operated by Elad, including the City of David Visitor’s Center and the future Kedem Compound. By registering the blocks of land, Israel is ensuring that it has solidified those land rights either registered to the state, to settlers, or to Elad.

What makes this more concerning is that, if you look at the map, Israel has strategically drawn the blocks to cover 90 percent of the settler homes in Wadi Hilweh. But within those blocks are Palestinian homes. And this is an indicator that Elad settlers and/or the state will target those Palestinian homes for Jewish settlement. This has obviously happened before and it’s expanding; beyond residential settlement and taking over Palestinians homes, now they’ve grown to include tourism development and archaeology.

And so, we believe the reason they are targeting Wadi Hilweh is because of its political and religious significance, and because of the fact that settler enclaves and settlements are located there. SOLT ensures the finality they want, solidifying land ownership and making it nearly incontestable. Whether Palestinians are rendered homeless and dispossessed as a result is not of concern to them.

JS: Is the Old City targeted for land registration?

AC: At this point, we can’t be certain, but we believe so, yes, but we can’t know when or why. For instance, they decided to initiate the pilot stage in the Umm Haroun section of Sheikh Jarrah, but no other area in Sheikh Jarrah has undergone the process. Why? It defies reason. Our speculation, our conclusion, is that it’s very much driven by their own interests of where settlers are located, where there is land that can be easily appropriated through the process, and where there’s land that is designated for a new settlement.

The documents they released indicated that all of East Jerusalem will be registered within five years, and it’s been five years since 2018, but they haven’t completed the process yet. If I remember correctly, they were aiming to have completed 50 percent of the process after two and a half years, but they’re not even close. So, it remains to be seen.

The budget for the plan ended in May 2023. The government was supposed to renew the decision, but there was a lot of foot-dragging and pushback, particularly from the very extreme right in the government. Even though they are fully behind increasing Israeli sovereignty in East Jerusalem and expanding settlements, I think that for them, any sort of investment in East Jerusalem is a huge no-no. There was a lot of pushback from the finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, and others, and what they agreed was to issue a statement that one month after Jerusalem Day, they would issue the details of the decision. They have yet to release the details of that decision.

The question remains whether or not the settlement of land title will continue. What we believe is that regardless of whether or not there’s a new decision, they will find a way to continue SOLT, whether it’s under Decision 3790 or a different one. It is continuing, on a monthly basis. Our coordinator of the monitoring project issues updates every month of what has taken place, and what he’s found according to the government maps is that there’s always something new. For example, the day before we released the paper, we found that they had added another block in Wadi Hilweh. And again, we are not aware of any block being for the benefit of Palestinians.

And again, to our original point, we have not found that there is one example of any block being settled for the benefit of Palestinians. It’s all for the advancement of the state or settlers. And then the outliers are church land, which was in the report.

JS: What do you believe needs to be done about this situation?

AC: In the report, we turn to the international community to demand Israel completely halt the process because of its implication for Palestinian land rights. Even if the process were to actually benefit Palestinians in terms of urban development and socioeconomic issues, the outcome would still be the same: Israel wants to ensure that Jews maintain a demographic majority in the city, effectively dominating it. As a result, they want to ensure that there is no room for territorial compromise with the Palestinians in the future. They would never, from our perspective—and as it can be demonstrated—walk back from this.

At this point, in the absence of a peace process and in the absence of a one-state vision where all are afforded complete equal rights, SOLT needs to be halted. As the report shows, it’s already a near-impossible process for Palestinians. The very few who have been able to get building permits over the years are now being subjugated to the SOLT process in order for them to continue to build and develop their properties—to the point where it’s now impossible to do anything without entering into this process, the very process that will ultimately lead to their dispossession.

The settlement of land title just needs to be completely ceased. It needs to be eliminated altogether, both for the benefit of Palestinians, and in order to preserve a modicum of conditions for some sort of political resolution in the city.

Notes

Ir Amim and Bimkom, “New Analysis Paper & Status Report: The Grand Land Theft—Ramifications of Israel’s Registration of Land Ownership in East Jerusalem,” June 25, 2023.