Overview

Credit:

iStock Photo

The Complex and Unresolved Status of Land in East Jerusalem

Snapshot

The status of land in East Jerusalem is very complex and unresolved for a myriad of reasons. This Backgrounder explores the historical relationships of ruling states to Palestinian lands, from the Ottomans and British to the Jordanians and Zionists, in order to lay the foundations for explaining how and why the Israeli state strategically manipulates the process of land settlement and registration in Jerusalem for its benefit; namely, the Judaization of the city and displacement of its Palestinian population.

A companion Backgrounder, Land Settlement and Registration in East Jerusalem, examines the historical motivations behind Israel’s decision to freeze land settlement and registration (LSR) in 1967 and the risks and opportunities of the land provisions of Government Decision 3790 for Palestinian Jerusalemites.

Land settlement means the settlement of rights of title to a piece of land. Once the rights have been settled, the land can be registered and an official title issued. In Jerusalem today, this process of land settlement and registration (LSR) is a burning issue, because it threatens Palestinians’ property rights, both individually and collectively.

In order to understand why, we must examine LSR more closely and contextualize it historically in Palestine.

Defining land settlement and registration

A given community’s relationship to the land is not static; it is dynamic, changing, and readjusting to suit prevailing socioeconomic and political policies, as well as societal transformations. This often leads to land fragmentation, as land is passed down to the next generation, and land transactions and real estate deals are completed. In this way, the purpose of instating more formal land regimes is to determine landowners, the location and borders of the plot or parcel of land, how someone becomes an owner, how land transfers from one party to another, and how the land is valued and taxed.

Formal and modern land regimes managed through state laws differ from traditional, informal land regimes managed through communal and customary norms, traditions, and religious laws. Transferring the land regime from a traditional, informal, and customary one to a modern, formal, and government-regulated one begins with land settlement and registration. Later, once comprehensive registration has been completed, regulations can be readjusted to fit population growth, urbanization, development rates, needs for balancing between open spaces and built-up areas, and so forth.1 Generally speaking, LSR is part of a community’s land regime, and should evolve to serve the community.2

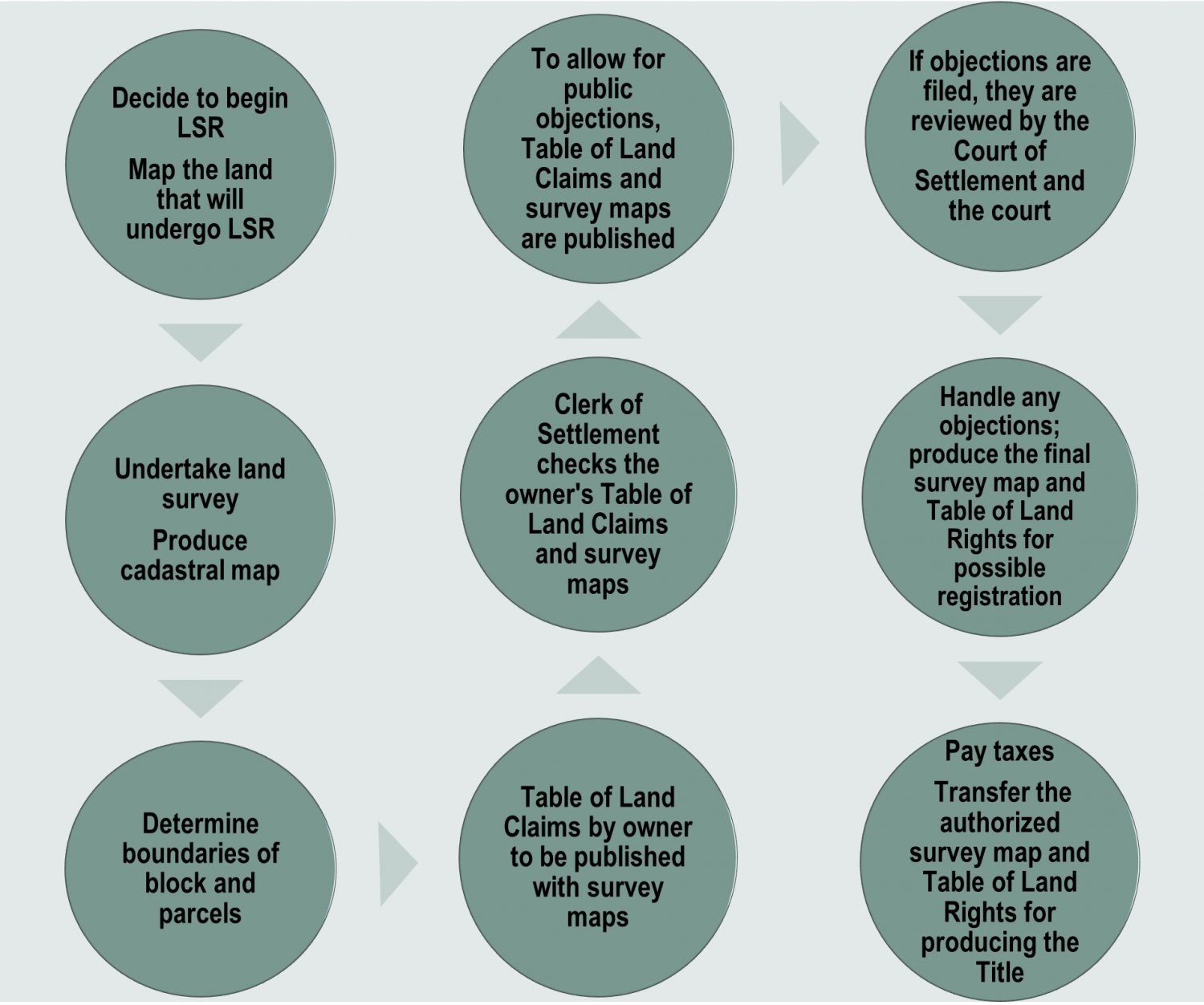

More to the point, land settlement (taswiya in Arabic, and hesder in Hebrew) connotes a precise, multi-step professional process undertaken to formalize the land’s status, specifically: surveying the land to determine its precise location, area, and borders, and allocating it to a designated owner(s) or user(s). Once land settlement is finalized, the owner can then request an official title to the piece of land that demonstrates his or her legal relationship to it. By contrast, land registration alone refers to registering a given plot of land in the Land Registration Bureau according to the land law.3 In Israel, this bureau is referred to as the Tabu, a holdover term from the Ottoman period.

Today, land settlement and registration in East Jerusalem comprise part of a trap that affects Palestinians’ land ownership. It is one of several means through which Israel implements a sophisticated matrix of control over the Palestinians of the city, with the aim of stripping them of their properties and handing them to Jewish buyers.4

LSR in Palestine in historical context

Over the course of the last century and a half, four formal land regimes have functioned simultaneously, or in parallel, in East Jerusalem, alongside the traditional, customary ones that have existed for centuries. The four formal ones are the:

- Ottoman land regime

- British Mandate land regime

- Jordanian land regime

- Israeli land regime

From 1516 to 1917, Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire, and the legal system in Palestine was based primarily on principles of Islamic law. From around 1840, a new era of reforms (the tanzimat in Turkish) brought “reform regulations aimed to centralise, modernise and to some extent secularise the Ottoman Empire,”5 in order to mobilize resources required for modernization with the aim of preserving the Ottoman state.

Most significantly for the purposes of this Backgrounder, the first formal land regime in Palestine, including Jerusalem, began with the passage of the 1858 Land Code and the Ottoman Civil Code (or majalla in Arabic),6 which was drafted over many years and fully ratified in 1877.7 The 1858 Land Code marked the beginning of systematic land reform and required landowners to register ownership. Ottoman land laws classified land into five types: mulk, miri, waqf, matruki, and mawat.8 Then, following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War One, and with Britain’s occupation of Palestine for 30 years starting in 1917, British Mandate authorities added a sixth type: musha.

The definitions of each type are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Land classifications under Ottoman and British Mandate law*

| Type of land | Definition |

|---|---|

| mulk | Privately owned land; individuals able to prove cultivation for 10 years were given a title (koshan) of ownership |

| miri | Land leased from the state; also included common and communal lands; cultivation was required for the lessee to use the land; leaving the land fallow for more than three years would result in dispossession |

| waqf | Property in trust to be administered by Islamic endowments and used for a religious or charitable purpose |

| matruki (“leftover”) | Land for public use, such as for roads |

| mawat (“dead”) | Land which is not owned or used by anyone; vested in the government |

| musha | Lands under the control of the government by treaty, convention, agreement, or succession; lands acquired for public purpose; collectively held land, such as by a village |

*Source: BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, “Land Ownership in Palestine/Israel (1920–2000)”; Najeh S. Tamim, “A Historical Review of the Land Tenure and Registration System in Palestine,” An-Najah University Journal for Research—A (Natural Science) 9, no. 1 (1995): 1–14.

These laws also guided land registration according to the old method of “registration in the bill book,”9 which means defining the owner of a given plot of land purely for the purpose of paying taxes.

During the British Mandate (1917–48), authorities adapted part of the Ottoman land regime and made some amendments, merging between the old and new methods based on the Torrens title system (see Figure 1), a system of land settlement, registration, and transfer in which the government (i.e., the Land Registry Office) is the keeper of all land records, and in which a land title serves as a certificate of indisputable ownership (see Land Settlement and Registration in East Jerusalem). The British system was implemented with the 1928 Land Settlement Ordinance—Property Rights Settlement, and with the establishment the Department of Land Surveys that same year.10

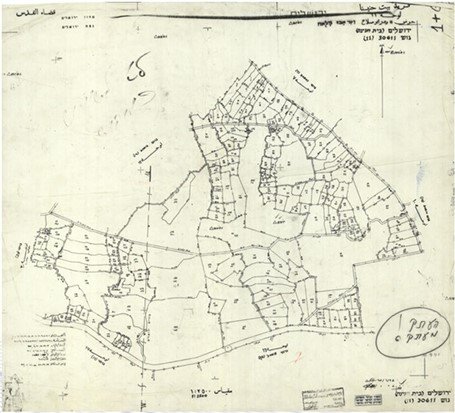

British Mandate authorities inaugurated a new era in which cadastral maps satisfied the demand for quality mapping and for an advanced system of land registration. However, by the time it ended in 1948, the British Mandate administration had completed the land settlement of less than 20 percent of the total country area (26,300 sq km),11 prioritizing the coastal plain “where Jewish interests in land purchase prevailed” over the mountainous areas.12 The fact that land settlement and registration were not completed under the mandate’s cadastral project has since remained a source of dispute over land ownership—both on the national level between Israelis and Palestinians, and on the individual level between Palestinian landowners.

After the division of Palestine in 1948, the West Bank, including the eastern half of Jerusalem (see Where Is Jerusalem?), was annexed by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, which continued to implement the British Mandate land regime with amendments, such as the 1952 Law of Land and Water Settlement (No. 40).13 According to this law, Jordan continued to undertake LSR. However, Jordan did not complete this work in most of the area of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

After it occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, in 1967, Israel extended Israeli law and administration over about 71 sq km of the land it occupied in East Jerusalem and beyond it, appending this territory to the Israeli Jerusalem municipality (see Where Is Jerusalem?). Over this area, Israel imposed Israeli law, including its land regime, in violation of several international laws and UN resolutions. However, the Israeli government decided to freeze Jordanian LSR in 1967. The resulting situation was complex: de jure, Israeli laws include the land regime, but de facto, work continues with the old method. That is, the informal land system is selectively used, in which traditional customs and norms are considered without undertaking an official land registration and producing a land title according to the Torrens title system.

What is more, upon occupying East Jerusalem in 1967, Israel granted the Palestinians living there the legal status of permanent residents, rendering precarious their legal rights to their properties14 (see Precarious Not Permanent: The Status Held by Palestinian Jerusalemites, Part 1 and Part 2). When it came to Palestinian institutions that existed in East Jerusalem, Israel abolished the Jerusalem Arab (Jordanian) municipality and numerous village councils, as it did in al-‘Isawiyya and Shu‘fat, and turned their authority and responsibilities over to the new Israeli Jerusalem municipality, which was charged with managing both East and West Jerusalem, administering a newly expanded, merged jurisdiction of about 126 sq km according to Israeli law. Therefore, with respect to the management of real property, the Israeli land regime replaced the Jordanian land regime.

While Palestinians generally believed that the Ottoman and Jordanian land regimes’ interests aligned with their own, they have felt unsafe and oppressed under the British Mandate and Israeli land regimes. This has been exacerbated with Israel’s continued occupation of East Jerusalem, which creates tensions and contradictions between the state’s formal land regime system and its informal, customary land regime (see Table 2). In turn, this creates barriers and obstacles to land settlement and registration, as explained in Table 2.

Table 2: Existing land regimes in East Jerusalem

| Traditional land regime | Modern land regime | |

|---|---|---|

| Land registration system | Deeds registration system Land ownership is authorized by a deed, derived from a customary, nonofficial, nontransparent process of defining the area and boundary of the land and determining its ownership; this gets entered in the “Deeds Register” |

Land rights system Land rights derive from a “title,” which is an official document issued by the state that defines the area, boundary, and ownership of the land after an official and transparent process; this gets entered in the “Rights Register” |

| Method of land registration | Old, traditional, community-based Private landowner initiates process |

New, centralized, state-based Government initiates process |

| Evidence for land ownership and belonging | Land registered according to deeds (sanad tasjil), used during the Ottoman and British periods A deed, while used to claim ownership and levy taxes, did not need a survey map to objectively establish exact location, borders, or area of a land |

Land registered through a title requires determining precise geographical location, borders, and area of the land, which must correspond to a survey map conducted by a state-appointed expert |

| Evidentiary value in demonstrating land ownership | Considered circumstantial evidence, including third-party testimonies Not accepted in a court of law, planning committee, or bank |

Considered fully admissible evidence, de facto and de jure, for a court of law, planning committee, or bank |

| Consequences and implications The existence of these conflicting land regimes in East Jerusalem makes the process of transition from one to the next complex and disorderly, giving rise to tensions between the state and landowners, and between landowners themselves. As a result, the registration and development of land—a critical resource in the city—is significantly impeded. |

||

Source: The table was created by the author.

The Current Status of LSR

Today, the processes of LSR in East Jerusalem are very complicated. This is due, on the one hand, to the several land regimes that are still used selectively by various communities in East Jerusalem; and on the other, to the Israeli government, which aims to separate Palestinian landowners from their lands and allocate to them a status that is temporary to make it easier for the state to confiscate them by whatever means (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property in Jerusalem). In addition, today, Israeli laws and regulations related to land settlement, registration, readjustment, planning, and management are centralized and complex. For example, Israel’s unilaterally imposed municipal borders are not aligned with village borders. When Israel expanded the borders of Jerusalem in 1967, it did not consider land settlement. Therefore, Israeli municipal borders ignore the preexisting blocks, parcels, and village borders that were recorded in Ottoman, British, and Jordanian land records.15

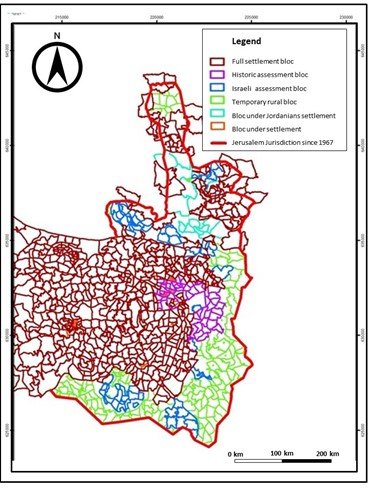

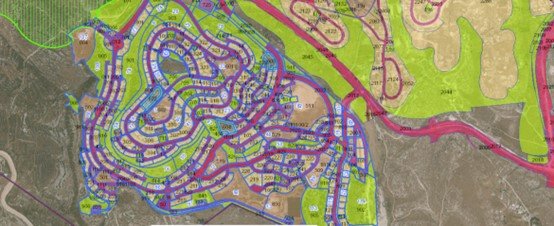

When they determined the borders of Jerusalem in 1967, Israeli officials were primarily concerned with adhering to the principle of acquiring the most amount of territory with the least number of Palestinians16 (see Where Is Jerusalem?). As a result, where existing villages began and ended was of no consequence to Israeli authorities. Therefore, within the newly expanded municipal borders of Jerusalem lay land that belonged to about 28 Palestinian villages, in addition to the Old City. Since 1967, some of these villages have followed the traditional land system, such as Sur Bahir, Silwan, and al-Sawahira. Other villages began, even before 1967, to follow the modern land system, including Beit Hanina and Hizma (see Figure 1). The Israeli authorities have not taken these different realities into consideration.

Moreover, different Israeli government bodies administer land in Jerusalem. One belongs to the Ministry of Justice and is called the Land Registry and Settlement of Rights Authority.17 It manages the process of land settlement up through the point of full registration and issuance of land title according to the Torrens title system.18 The second belongs to the 1963 Treasury Ministry and is called the Israel Tax Authority.

When they determined the borders of Jerusalem in 1967, Israeli officials were primarily concerned with adhering to the principle of acquiring the most amount of territory with the least number of Palestinians. According to the Land Tax Law (Betterment and Purchase) and its later amendments, any person who wants to register land or conduct activity that changes the status of land acquisition has to report to the Tax Authority, pay taxes, and gain the right to use the land, which would still not be registered and considered to have passed settlement. This is required of both types of land registration under the traditional and modern land systems. The main difference relates to the complexity of determining to whom the land belongs. In the modern land system, the process is clear, faster, and free of third-party involvement. In the traditional land system, by contrast, and due to the possibility of registering the land according to the Land Tax Law, the private landowner, who is recognized by the traditional land system, can request and obtain a building permit after presenting required evidence that they have the right to use the land and build on it in accordance with the Israeli government and Jerusalem municipality regulations. This evidence includes certification from the village mukhtar and signatures from neighbors attesting to the validity of the claim. In other words, Palestinian lands are often registered twice (according to the traditional and modern systems), and they are subjected to complex legal and political restrictions by two Israeli governing bodies, rendering engaging successfully in the process of LSR for Palestinians virtually impossible.

This has been made more impossible by the fact that Israel froze LSR for 51 years between 1967 and 2018. The decision to freeze LSR emerged out of the complexity of the LSR process, which imposed barriers to distinguishing state land from private land (see Land Settlement and Registration in East Jerusalem). The Israeli government used its legal might to confiscate land directly as an alternative to doing so through LSR.19 From the land that remained after the Israeli state confiscated what it wanted for the construction of Jewish settlements, it enabled landowners to continue following the four previous land regimes (customary, Ottoman, British Mandate, and Jordanian). In some cases, communities could find ways to navigate between these myriad regimes based on established norms and customary, informal laws; in others, contradictions in implementation and interpretation arose, leading to land disputes. These disputes were then handled in the Israeli courts, where judges sometimes attempted to base their decisions on a hybrid of multiple land regimes, taking into consideration the Israeli laws that added yet another layer to the complexity of land disputes in the city.

Indeed, managing land on illegally and militarily occupied territories is no simple matter. That is to say, vast amounts of Palestinian lands, especially in occupied East Jerusalem, have not been officially registered. Despite Israel’s adoption of the Torrens title system, today, about 3 percent of the area of Israel within the 1949 Green Line—including East Jerusalem, as far as Israel is concerned—is still registered under a deeds registration system used in the traditional land system. In fact, about 90 percent of the area of East Jerusalem is registered under a deeds registration system.

Another complication arises as a result of the diverse sociocultural makeup of Palestinian communities in East Jerusalem, implying different sorts of land use, whether urban, rural, agricultural, or cultivable. Three communities exist in East Jerusalem: urban, rural, and Bedouin. These varied community structures have a direct impact on land catchments—i.e., the area of land that is used and owned by persons, families, and tribes. This diverse classification has a direct influence on the size of owned land, on the determination of the land’s value for purposes of taxation, and on the type of documentation that shows how the land is owned.

Moreover, since Israel occupied East Jerusalem in 1967, the city’s Palestinian community has grown dramatically in population, and there have been widespread changes in land ownership. In 1967, about 68,000 Palestinians were living in East Jerusalem; today, a conservative estimate is that that number has grown to about 366,80020 (see Who Are the Palestinians of Jerusalem?). The Palestinian population in East Jerusalem has also witnessed urbanization and development, and combined with an active land market and land ownership transformation, much has changed over the course of 50 years in terms of land status and ownership. Today, some landowners and users who claimed land during the Jordanian land settlement process have either passed away or left the area. Under Israeli law, this means they can be considered “absentees” and their land is automatically transferred to the Israeli Custodian of Absentee Property. The office of the Custodian of Absentee Property “has routinely turned over properties under its control to [Jewish] settler and settler-related projects”21 (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property in Jerusalem).

Some of what Israel defines as “absentee” property falls within what has been defined by British Mandate and later Jordanian land registration authorities as a “temporary rural block” for taxation matters. These lands were not included in the Jordanian settlement process conducted before 1967, and still function and are managed according to a traditional land system. As a result, they face more complicated problems related to determining who owns the land, where the land’s boundaries lie, the area of the parcels, and how to divide them among multiple owners.

But none of these historic designations carry weight against Israel’s ideological and political priorities. Driven by settler-colonial imperatives, Israel’s land policy aims to take ownership and control of as much land as possible through oppressive legal, military, and political maneuvers.22 That is, the Israeli state assumes that it owns the land under its sovereignty, except if landowners can present indisputable proof according to complex and cumbersome Israeli legal requirements, which enables them to register the land as private land. If not, the state will register the land as state land, such as what happened to the Bedouins in the Naqab.23 In other words, Israel is not interested in initiating a citywide land settlement and registration process in Jerusalem, because as far as it is concerned, this land belongs to the Jewish people as represented by the Israeli state and the Jewish National Fund (JNF). Moreover, Israel considers it de jure state land, despite it being used de facto by private parties who can register the land, provided they meet the state’s requirements for doing so.

More specifically, Israel has used a 1943 law passed under the British Mandate called the Land (Acquisition for Public Purposes) Ordinance as an effective tool to confiscate privately owned Palestinian land in East Jerusalem.24 From 1967 to 1991, Israel confiscated about 26.3 sq km from the originally occupied territory of about 71 sq km (see Where Is Jerusalem?).25 Still, about 44.4 sq km remain that have not been officially confiscated. Most of this unconfiscated area has not passed through LSR, and part of it (about 1.4 sq km) that passed through LSR before 1967 needs land readjustment to fit the LSR to the new realities that exist after so many years. Therefore, about 43 sq km, which comprises about 60.5 percent of land in the East Jerusalem before it was expanded by Israel in 1967, lacks official settlement and registration. In a 2013 survey, Israeli NGO Bimkom—Planners for Planning Rights26 revealed that the Israeli Jerusalem municipality has made plans for about 37.3 sq km of this area, while just about 26.4 percent of the planned area (i.e., 9,844.3 dunums) in East Jerusalem is allocated for Palestinian residential purposes (see Table 3). Besides this, about 5.7 sq km (12.8 percent) of East Jerusalem is still not included in approved local plans that need to be settled and registered, and authorized by the Israeli planning system to issue building permits.

Table 3: Primary zoning designation according to approved Palestinian neighborhoods (plan prepared and authorized by the Israeli government, 2013*)

| Zoning | Area (dunams) | Percent % |

|---|---|---|

| Open space | 10,474.5 | 28.1 |

| Residential | 9,844.3 | 26.4 |

| Roads | 5,621.6 | 15.0 |

| Public buildings and institutions | 1,863.6 | 4.9 |

| Area for future planning | 458.5 | 1.2 |

| Commercial areas | 281.0 | 0.7 |

| Mixed residential and commercial | 73.6 | 0.02 |

| Cemeteries | 172.4 | 0.4 |

| Hotels | 144.0 | 0.3 |

| Engineering facilities | 86.6 | 0.02 |

| Light rail | 81.6 | 0.02 |

| Other** | 8,198.0 | 29.97 |

| Total area of survey | 37,300 | 100.0 |

*Source: Efrat Cohen-Bar and Sari Kronish, eds., Survey of Palestinian Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem: Planning Problems and Opportunities (Jerusalem: Bimkom, 2013), 11.

**Unplanned areas or areas planned for Israeli institutions, the Atarot industrial zone, the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, and Israeli settlements in the heart of Palestinian neighborhoods

A Complex Modern Land Classification System

Today, Israel imposes six kinds of blocks on all land in Jerusalem, both East and West, as a way to determine through which steps of the LSR process they have passed, and/or the type of registration system under which they are recorded. The blocks are as follows:

1. Full settlement blocks: Land that has undergone the full LSR process according to the Torrens title system and is divided into blocks and parcels that are fully registered with proven ownership. This type of block is found in three areas of the city:

- West Jerusalem

- Blocks that fall within the areas of the Palestinian villages of Hizma and Qalandiya (see Figure 2) but have been confiscated for Israeli use

- Beit Hanina in East Jerusalem, which has two blocks that are fully under Palestinian use; these are War Abu Salah and Hud al-Tabal (see Figure 3)

2. Historic assessment blocks: These blocks are concentrated in the area around the Old City. Some of them are found within the pre-1967 jurisdiction boundary of the municipality as it existed under Jordanian rule. The land parcels in these blocks have been registered and defined according to a “Physical Cadastral Mapping” to determine the tax rates on those parts of the land that could be registered according to the traditional deeds registration system.

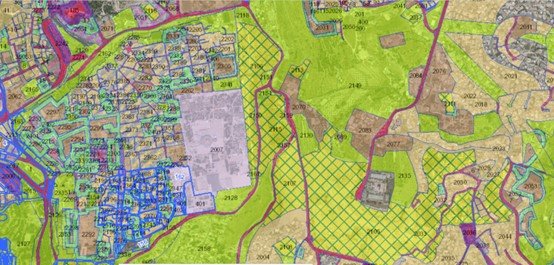

3. Israeli assessment blocks: Using the 1943 Land (Acquisition for Public Purposes) Ordinance, the Israeli government confiscated these blocks of land before they had officially passed through settlement and registration. It then registered them according to Title No. 5 and 7 of Israel’s 1969 Land Law, which means the state took possession of the blocks. Moreover, after building Israeli settlements upon them, the state used Title No. 19 of the Israeli Land Law to register them in the name of the State of Israel and to define them as state land. This occurred without completing an official settlement process, and was done according to what is termed “first registration,” using what is known as plan/mapping for registration (tatsar in Hebrew). See Figures 4a and 4b for examples.

4. Temporary rural block: Some of the areas within the assessment blocks passed “first registration” according to the Ottoman deeds registration system during the Ottoman period. Under the British Mandate, part of these areas passed a physical cadastral mapping and assessment for tax purposes, according to the mukhtar’s land records, and later were registered under the Jordanian land regime. And then, part of these areas did not go through any registration since they were classified as “dead land” (mawat), according to Ottoman land law. This area comprises about 60 percent of the 44 sq km of land in East Jerusalem, not including the land that was confiscated by Israel, and is distributed across the Old City and south of East Jerusalem (see Figure 4).

5. Blocks under Jordanian settlement: This includes the blocks that were settled during Jordanian rule (1948–67) when Jordan undertook modern LSR to replace the traditional deeds registration system. For these blocks, tables of land claims exist, and some of them were published by the Jordanian government before 1967 for the purpose of allowing public objections; however, they were not subsequently authorized to be officially accepted as evidence of rights to the land, which would mean that official titles could be produced for each of these land parcels, excluding matruki parcels. Most of these blocks are located in Shu‘fat and Beit Hanina in East Jerusalem.

6. Blocks under Israeli settlement: This includes areas that were already settled and registered according to the Jordanian land regime, with definitive documentation such as cadastral mapping and a registered table of land claims. Examples include block no. 30605 (Block 5 Beit Hanina) and block no. 30606 (part of Block 6 Beit Hanina). However, after registering them as matruki, Israel registers them under the name of the Israeli government or Israeli Jerusalem municipality.

Conclusion

Considering the complexity of land classifications according to the aforementioned six blocks, as well as the convoluted and imbricated land regimes that exist in East Jerusalem, the exact picture of land use in the city is very difficult to assess with precision. That is, it is difficult to ascertain the level and kind of registration to which blocks, parcels, and entire swathes of Palestinian land have been subjected.

According to our estimates, the percentage of land in East Jerusalem that has been registered based on final settlement according to the Torrens title system is less than 10 percent, while land registered according to the deeds registration system reaches about 50 percent. While there are various methods of land registration among the different land regimes that exist in Jerusalem, they are mostly not recognized by Israeli authorities. This creates a situation whereby Palestinians continue to lose ownership of their lands, thus shrinking the space and presence of Palestinians in Jerusalem. But, as of 2018, Israel has resumed the process of LSR using the Torrens title system in East Jerusalem, a controversial decision which will undoubtedly have lasting implications for the city’s Palestinians. This is explored in the accompanying Backgrounder, Land Settlement and Registration in East Jerusalem.

Contributors

Editors: Kate Rouhana and Nadim Bawalsa, Jerusalem Story

Notes

Felipe Francisco De Souza, Takeo Ochi, and Akio Hosono, eds., Land Readjustment: Solving Urban Problems through Innovative Approach (Tokyo: JICA Research Institute, 2018).

Harold Demsetz, “Toward a Theory of Property Rights,” American Economic Review 57, no. 2 (1967): 347–59.

Joshua Portman, “An Introduction to Understand Land Registration and Ownership in Israel,” Buy It in Israel, 2022.

Rassem Khamaisi, “The Trap of Urban Planning Development in Jerusalem,” Contemporary Arab Affairs 12, no. 2 (2019): 105–38.

Birzeit University Institute of Law, “Legal Status in Palestine.”

Birzeit University Institute of Law, “Legal Status in Palestine.”

Kenneth Stein, The Land Question in Palestine, 1917–1939 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

Dov Gavish and Ruth Kark, “The Cadastral Mapping of Palestine, 1858–1928,” Geographical Journal 159, no. 1 (1993): 70–80.

Hilik Horovitz, “Department of Surveys Offices in Northern Israel,” Survey of Israel, 2007.

Alexandre Kedar, Ahmad Amara, and Oren Yiftachel, Emptied Lands: A Legal Geography of Bedouin Rights in the Negev (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018), 84.

Iyad Issa, “Caught between the Lines: Cartographic Narratives of the Palestinian Village of Dayr Ayyub from the First World War to the Present,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 81 (2020).

Mu’assasat al-Qawanin wa-Ahkam al-Mahakim al-Filastiniyya, “Land and Water Settlement Law No. 40 of 1952” [in Arabic].

Walid Salem, “Jerusalemites and the Issue of Citizenship in the Context of Israeli Settler-Colonialism," Holy Land and Palestine Studies Journal 17, no. 1 (2018): 25–41.

Salman Abu Sitta, “Confiscation of the Palestinian Refugees’ Property and the Denial of Access to Private Property,” Memorandum submitted to the UN Social, Economic and Cultural Rights Committee, BADIL submission, November 14, 2000, Geneva.

Nur Masalha, Maximum Land and Minimum Arabs: Israel, Transfer and Palestinians, 1949–1996 (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1997).

Ministry of Justice, “Land Registration” [in Hebrew].

Theodore B. F. Ruoff, An Englishman Looks at the Torrens System (Sydney: Law Book Company of Australasia Pty Ltd., 1957), 106.

Geremy Forman and Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar, “From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22, no. 6 (2004): 814.

Omar Yaniv, Netta Haddad, and Yair Assaf-Shapira, Jerusalem Facts and Trends 2022: The State of the City and Changing Trends (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, 2022), 20.

Daoud Kuttab, “Jerusalem Absentee Law a Major Roadblock to Peace,” al-Monitor, June 6, 2013.

Baruch Kimmerling, Zionism and Territory: The Socio-territorial Dimensions of Zionist Politics (Berkeley: University of California Institute of International Studies, 1993).

Kedar et al., Emptied Lands.

B’Tselem, “Under the Guise of Legality: Declarations of State Land in the West Bank,” March 2012.

Chaim Zandberg, “Jerusalem—Settlement and Confiscation of Land Rights” [in Hebrew], HaMishpat, accessed November 14, 2022.

Efrat Cohen-Bar and Sari Kronish, eds., Survey of Palestinian Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem: Planning Problems and Opportunities (Jerusalem: Bimkom, 2013).