Fawzi Shaaban, head of the Silwan Association of Institutions, said in an interview with Jerusalem Story that “if homes will be confiscated and families displaced, we are talking about a real catastrophe that goes beyond the Nakba. Those homes are all that these families own. They will not give up their right to their land, and I know that they are ready to make all sacrifices needed to protect their homes.”10 He continued that even if they are forced to leave their houses, and even if they demolish them, they will build tents in their place.11

Many residents, fearing potential legal repercussions from Israeli authorities, have chosen not to voice their grievances publicly. They view the decision as a catastrophe, as the targeted homes hold generations of memories and serve as the only Palestinian refuge in Jerusalem, already grappling with a severe housing crisis due to Israeli policies, which essentially only address the housing needs of the city’s Jewish population.12

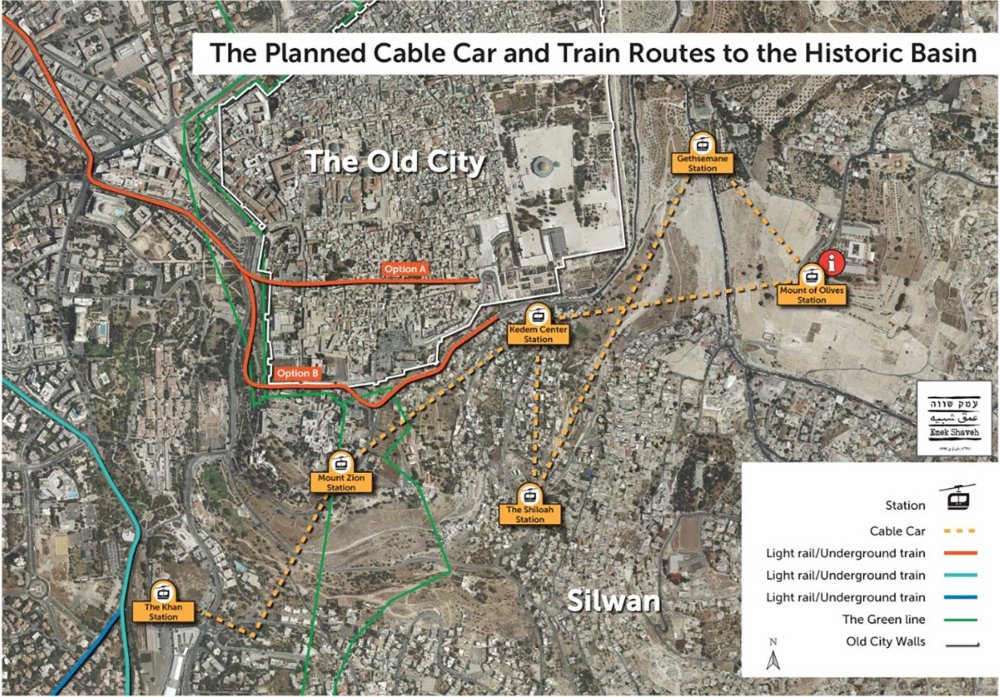

The cable car project is poised to reshape the landscape of the ancient city, further erasing the armistice line—the 1948 Green Line. If completed, the project will radically transform the core of Jerusalem, intensifying Palestinian displacement from Silwan and beyond.

Jerusalem Story contacted the Israeli spokesperson of the Jerusalem Municipality for a statement, but had not received a reply by the time of publication.