Though passed in 1950, the law worked retroactively by defining as an “absentee” anyone who had left their property as of November 29, 1947, and was any of the following:

- A national or citizen of Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Trans-Jordan, Iraq, or Yemen or located in any one of these countries

- Located in “any part of Palestine outside the area of Israel” (i.e., Israel’s borders of the time when the law was passed)

- A Palestinian citizen under the laws of the British Mandate (even if their status was unclear or undetermined) and left his residence for a place outside Palestine before September 1, 1948, or for a part of Palestine that was “held at the time by forces which sought to prevent the establishment of the State of Israel or which fought against it after its establishment”2

- Any body of persons in these categories (such as a board or corporation)

The definitions applied from that date until the day on which the “state of emergency shall cease to exist.”3 To this day, Israel has not removed the state of emergency, rendering millions of exiled Palestinians in the region today “absentees.”

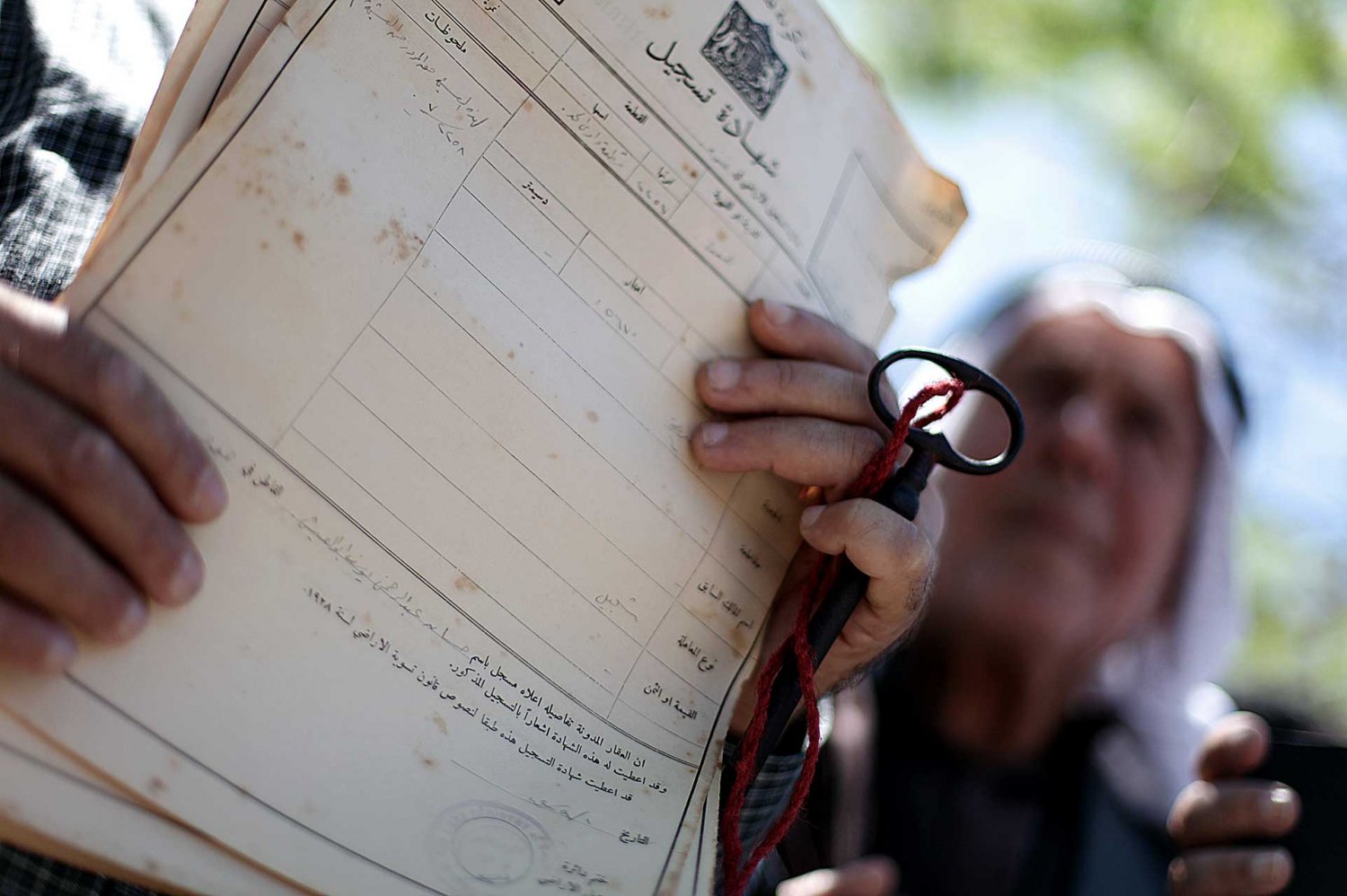

Moreover, the term “absentee” notwithstanding, the law’s formulation could and did mean that Palestinians who took refuge in the next village or in a relative’s village or any of a myriad of imaginable situations were automatically rendered into “absentees.” In effect, even if Palestinians exiled in 1948 whom Israel declared as “absentees” could find a way to return to their properties—even if they remained within the country—they could not claim them. Israel covered its bases, banning exiled Palestinians their right of return, and ensuring that none could reclaim their properties due to their status as “absentees.” Those who remained in the country were classified as “present absentees.” Under Israeli law, this status is passed on to one’s male children,4 meaning that even future generations had no hope of reclaiming property confiscated under this law.

When Israel occupied East Jerusalem in 1967, it enacted Military Order 58 Regarding Abandoned Property (1967), which stipulated that “abandoned” properties that were left vacant after the war and whose inhabitants were “resident of an enemy country” could be transferred to the Custodian of Absentee Property. Properties that were not vacant, however, were not transferred—yet. This was decided in an internal government meeting.5 In 1967, Israel also expanded the administrative and jurisdictional boundaries of East Jerusalem by 71 square kilometers, which de facto expanded the municipal boundaries of the city. That is, not only did the Absentees’ Property Law sustain the prohibition of Palestinians in East Jerusalem who were expelled from West Jerusalem in 1948 from their right to reclaim their original properties, but it made it so that: