Land Registration in East Jerusalem: A 51-Year Moratorium

Credit:

iStock Images

Land Settlement and Registration in East Jerusalem

Snapshot

In 1967, Israel froze the modern processes of land settlement and registration (LSR), in East Jerusalem, leaving the status of much of it in limbo. Land that is not fully settled and registered cannot be legally developed, because neither building permits nor mortgages can be issued. It can, however, be confiscated by the state. In May 2018, Israel announced its intention to undertake a comprehensive land registry there, as part of a five-year plan known as Government Decision 3790.

This Backgrounder examines the historical motivations behind Israel’s decision to freeze LSR in 1967, and then explores the risks and opportunities of the land provisions of Decision 3790 for Palestinian Jerusalemites. A companion Backgrounder, The Complex and Unresolved Status of Land in East Jerusalem, explores the historic underpinning of the status of land in the city.

In order to understand the land provisions of Government Decision 3790, which reinstated modern LSR in East Jerusalem after a 51-year suspension, we must first understand why Israel froze LSR in 1967. Today, about 90 percent of the land in East Jerusalem has not been formally settled and registered according to the modern Torrens title system.1 Simply, and unlike customary or religious land registration, in the Torrens title system, land ownership is confirmed by a court—upon approval of a landowner’s application—through issuance of a certificate of title. It was introduced in Australia in 1858 and was adopted in British Commonwealth countries and Europe. Why did Israel freeze land registration according to this modern, formal land system in East Jerusalem between 1967 and 2018?

One of Israel’s primary motivations for freezing LSR in East Jerusalem was to avoid conflicts among landowners, and between landowners and the state. Throughout historic Palestine, and wherever Israel has annexed or occupied land, the state has generally been interested in organizing its land regime to enable development, tax collection, and the provision of services to communities—depending on the availability of resources and the state’s priorities. In East Jerusalem, however, where the political status of the city was unclear in the decades following Israel’s military occupation in 1967, the Israeli government has not been interested in resuming and completing land settlement to avoid problems such as conflict over land ownership, building new settlements, and collecting taxes. Indeed, the decision to freeze land settlement in 1967 led to reduced land registration, lessening the burden of land governance on the state.

Besides this, the state was motivated to deter landowners from registering their land. Deterrence meant delay, which over time could mean developments such as relocations (to areas rendering the landowner an “absentee”), deaths of landowners, which could give rise to a dispute among their descendants, and so on. This reality in turn serves the interests of Israel, since absent landowners and disputes among Palestinians over lands facilitate their transfer to the state, or simply the prohibition of development on that land.2

Another reason for freezing LSR is the disputed status of East Jerusalem and the uncertainty about its ultimate disposition. Since 1967, the status of East Jerusalem has been unresolved. Israel’s behavior has reflected a sense of uncertainty as to whether Jerusalem would ultimately end up being divided in a final negotiated settlement with the Palestinians. For example, in 2012, former mayor of Jerusalem Ehud Olmert stated: “We avoided investing in areas which I think that in the future will not be part of the Jerusalem that will be under Israeli sovereignty.”3 This general attitude has changed with the passage of time and the extinction of any type of negotiations process or horizon. A critical turning point was reached in 2017, when the US Trump administration announced its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, breaking with international law and the global consensus on Jerusalem, about which more below.

The Palestinian community was likewise operating under a sense of limbo—surviving today to hang on for a brighter tomorrow; in Arabic, this state of perseverance is known as sumud. Many landowners have been waiting for the geopolitical situation to change and believe that they have the right to the land based on documentation they hold from the deeds registration system, or customary law, or de facto habitation or cultivation that could protect their rights to the land. On the other hand, they also behave under the assumption that the Israeli occupation will one day end, and that their status and living conditions will change. This geopolitical climate motivated the Israeli authorities to halt LSR, which would formalize the status of the land.

Moreover, modern LSR is cumbersome. The process of formal land registration is a complex one that requires considerable time and resources to fulfill the complicated requirements for registering a piece of privately owned land, whether it was acquired through inheritance or purchase. It is also very expensive, incurring costs at every stage—lawyers, surveyors, fees, taxes, and so on. The general cost varies from $15,00 per dunum (1,000 sq m) for open and agricultural land, to about $80,000 per dunum for developed and built-up land.4

There are also long-standing conflicts and disputes over land ownership in East Jerusalem that made freezing LSR convenient. These conflicts exist on two levels. The first is related to the conflict between landowners and the state, which uses various means to expropriate land, such as claiming land that was registered in the name of the Jordanian treasury as state land and authorizing the seizure of land registered in the names of Palestinians deemed “absentees” by the Custodian of Absentee Property (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property in Jerusalem). The second relates to the dispute over land between individuals—whether heirs, relatives, or neighbors. Such disputes also arise between Palestinians and Jews who claim the same land. When Jews are party to such disputes, they invariably enjoy the support of government institutions, agents, and courts, which emboldens and empowers them. Such interpersonal disputes over land take time, resources, and emotional energy as they proceed through the courts.

And when the land in question belongs to Palestinians in rural and tribal areas, the conflict with the authorities is particularly acute. Within more traditional Palestinian communities, such as in the rural and tribal areas, cultural norms and attitudes toward land registration are based in religious law, customary laws, and community norms and customs. In the context of fraught conflict and deep mistrust and contradictions, such as in East Jerusalem, the community has persistently clung to its traditional cultural codes and norms. As a result, it has not been sufficiently aware of, or informed of, the potential consequences of clinging to traditional habits. This gives rise to complicated and often tense processes of land registration, where the community and the state disagree on fundamental issues and engage in long, complicated, and frustrating proceedings. The Israeli authorities wanted to avoid such proceedings at all costs.

Finally, the Palestinian Land Authority (PLA) opposes LSR in the existing political context, and the Jordan Land Authority has refused to share data and land claims documented during the process of land title settlement before 1967, when East Jerusalem was under Jordanian control. As a result, Israel has not wanted to resume LSR in East Jerusalem to avoid further conflict with the Palestinian and Jordanian leaderships. Certainly, this has also made it challenging for Palestinians with claims to lands in East Jerusalem to effectively navigate the process of registering them.

Problems and consequences

Whatever Israel’s myriad causes for freezing LSR in East Jerusalem for 51 years, the lack of formal registration of so much of the land in the city has resulted in grave problems and consequences for Palestinian Jerusalemites. For starters, the Israeli government and the Israeli Jerusalem municipality have legal avenues for confiscating private land that has not been properly settled and registered (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property in Jerusalem). Should confiscation occur, the Palestinian landowner has no legal recourse or avenue to object and cannot claim or obtain any compensation under existing laws.

Furthermore, land that is not fully settled and registered cannot be legally developed, because neither building permits nor mortgages can be issued. Without a land title, Palestinians cannot request or obtain a building permit or, if they somehow manage to do so, they cannot apply for a mortgage, because banks require the ownership of the land to be established using the Torrens title system. As a result, the number of building permits issued to Palestinians in East Jerusalem is very low. From 2010 to 2014, of 10,750 building permit applications in the city as a whole, only 1,906 (15 percent) were submitted by residents of Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem. In this same period, from those applications, 6,960 permits were issued in the city as a whole, but only 965 (14 percent) were issued to applicants who lived in Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem.5

In this situation, the gap between the demand and supply for housing has grown because the Palestinian community cannot obtain building permits. Between 2009 and 2018, while construction of 26,737 apartments commenced in Jerusalem as a whole, only 4,900 (18.3 percent) of those were located in Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem.6 Based on our calculation, for each year from 2011 to 2017, the housing shortage in East Jerusalem was about 1,618 apartments.

Undoubtedly, the Palestinian community has suffered greatly from Israel’s severe punitive measures for building without a permit. In East Jerusalem, Palestinians who build without a permit can be penalized with steep fines and receive home demolition orders. Between 2004 and 2019, the Israeli authorities demolished 970 houses, an average of 65 per year.7 According to the Jerusalem municipal budget for 2018, the revenue for fines for unauthorized construction totaled about NIS 25 million in that year alone, about 70 percent of which came from homeowners in East Jerusalem (see Forcible Home Expulsions).8

And because Palestinian landowners cannot buy or sell land, the land market is stagnant. According to an Israeli study, the lack of an official land registration system in East Jerusalem has cost Palestinian residents an average of about NIS 80,000 ($23,000) per household, which means that each year, the lack of a proper land registration system has cost the entire population of East Jerusalem between NIS 630 million and 4.1 billion (between $180 million and $1.17 billion).9 To compare, the total annual income of Palestinians in East Jerusalem is estimated to be about NIS 3.5 billion ($1 billion).10 In other words, Palestinians pay the price of illegal construction.

What is more, on account of this system, every year, the Israeli Jerusalem municipality loses nearly a quarter of a billion NIS, and the Israel Water Corporation loses another 10 million NIS. The total loss to the Development Fund is estimated at a minimum of NIS 1.1 billion and as much as NIS 12 billion. This amount could be used to provide the basic infrastructure badly needed in East Jerusalem, among other things.11

These complexities mean that land is often stuck in a “dead zone,” creating “dead capital.” The inability to transfer land registered under the old deeds registration system, and from the traditional customary land regime to the newer Torrens title system, has effectively frozen the use and development of such lands. That is, they have become “dead capital” from which owners cannot benefit.12

And because Palestinian landowners cannot buy or sell land, the land market is stagnant. Beyond the relationship between Palestinians and the Israeli authorities, the problematic registration process creates and exacerbates disputes between Palestinian landowners and heirs to the land. By now, at least three generations of Palestinians have been born, inherited land, and passed it on to their heirs since the land was last registered before 1967. This means that many of the first-generation landowners who had first-hand knowledge of the land’s boundaries and other features are deceased, or are otherwise incapacitated or absent. The neighbors of the original landowner may have moved on or died as well, and the newer arrivals may not have the same relationship to, or shared understanding of, land boundaries and use. Each subsequent generation may also bring more heirs, resulting in ever-shrinking plots available to inherit, or large numbers of relatives co-owning the same plot. All these factors can foment disputes and prevent even a basic shared understanding about using the land at all.

Israel’s Plan to Resume LSR in East Jerusalem

On March 6, 2018, the Israeli Ministry of Justice’s Land Registry and Land Settlement Department announced that, according to Articles 5 and 9 of the 1969 Land Settlement Order, Israel would resume LSR in East Jerusalem under the Torrens title system. The Israeli government then passed Decision 3790 on May 13, 2018.13 The decision, which is the first comprehensive attempt to stimulate economic development in East Jerusalem, significantly expanded the Justice Ministry’s initiative. Under Decision 3790, the state allocated about NIS 2.1 billion over five years to a number of areas in East Jerusalem, including LSR.14

Under Article 6 of Decision 3790, it is stated that the decision is meant to direct the Ministry of Justice to carry out LSR so that at least 50 percent of the land in East Jerusalem will be reordered no later than 2021, and 100 percent of land registration in East Jerusalem will be completed by the end of 2025. To this end, NIS 50 million ($14 million) is allocated between the years 2018 and 2023. The process of LSR is entrusted to a team headed by the General Director of the Ministry of Justice, with the participation of the Treasury Office, the Office of the Representative of the Prime Minister, the Israel Land Authority, the Director of the Israel Mapping Center, the General Director of Planning Administration from the Ministry of Finance, and the General Director of the Jerusalem municipality.15

The following points explain the reasons behind Israel’s decision to resume modern LSR in East Jerusalem:

- Strengthening Israel’s sovereignty over East Jerusalem. Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked said: “This was the first practical application of [Israeli] sovereignty since the State of Israel’s decision to extend sovereignty in East Jerusalem following the liberation and reunification of the holy city in 1967.”16 This reflects a government emboldened by the US recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, something that almost no other country has done since 1967, with the consensus view derived from international law that East Jerusalem was acquired illegally by force and its final status must be resolved through negotiations between the parties.

- Enabling the government and municipality to regulate all land in East Jerusalem by 2025, including easing issuing of construction permits for residents.

- Reducing the socioeconomic gaps between East and West Jerusalem to demonstrate that the city has been “unified.”

- Phasing out the old deeds registration system, thereby enabling the consolidation of the city’s land regime into one formal and modern Torrens title system.

- Reducing intra-family disputes and violence over land.

- Ending land sharing between owners, and clearly differentiating between private and state land, including Jewish owners and land owned by absentees.

Decision 3790 differs from previous government decisions concerning East Jerusalem, as the main objectives of previous resolutions were articulated in explicit security vocabulary, while the main stated objective of Decision 3790 is to improve the economic, social, and humanitarian situation in East Jerusalem. Indeed, Decision 3790 calls upon Israeli decision makers to use the higher taxes collected from Palestinian areas to benefit East Jerusalem’s Palestinian population, and to use identified absentee lands to address Palestinian public needs—rather than handing them over to settler organizations as is typical.17 In other words, Israel is clearly aware of the complexity of the problem of absentee owners for LSR.

However, it is critical to understand that this decision is meant to confer full sovereignty to Israel over East Jerusalem, an area whose status is disputed and under Israeli occupation. Indeed, in an interview, Justice Minister Shaked said:

The day before the strengthening of Jerusalem through the transfer of the American embassy to Jerusalem, and after decades of Israeli sovereignty in eastern Jerusalem, we are strengthening the city and actually applying sovereignty through the program of land regulation in East Jerusalem, as exists elsewhere in Israel. Moreover, this is also important for the residents of East Jerusalem. In the absence of such a move, the owners of the land rights are prevented from exercising their right to it, including the issuing of building permits. Here, sovereignty and the welfare of the residents come together.18

In extending Israeli sovereignty over the occupied part of the city, Israel is effectively advancing its annexation of it, a move which is illegal under international law. In fact, the Justice Ministry had already begun LSR in the East Jerusalem neighborhoods of Beit Hanina, Sur Bahir, and Mount Scopus earlier in 2018. Decision 3790 significantly expanded the process.

As mentioned, land that is not registered lacks official rights to it, which leads to land disputes between Palestinians and Israeli developers. As a result, the Ministry of Justice, as stipulated in Decision 3790, seizes lands through the Absentees’ Property Law, among other tactics, as a way to avoid such conflicts. In response to this skewed system, a coalition of Palestinian organizations in East Jerusalem has opposed the government’s initiative to register the land. This has placed obstacles in the government’s ability to implement Decision 3790, especially regarding the issue of land taxes. Moreover, while the plan is meant to establish order and provide development in Palestinian East Jerusalem, it does not make provisions for reducing the harsh discrimination that typifies Israeli planning for Palestinians in East Jerusalem.19

Moreover, a close reading of Decision 3790 shows that disbursement of funds is conditional on securing individual integration and development in the Israeli system, as well as—in the case of education—allocating resources to those who study in Israeli universities and colleges, or in the small percentage of Jerusalem schools that adopt the Israeli curriculum.20 In this regard, a relatively limited amount of resources is allocated for planning and LSR. Indeed, only NIS 50 million (about $15 million) were allocated for this critical work, which is less than 2.5 percent of the total funds allocated in the entire plan.

In other words, the Israeli state’s decisions and policies must be considered within the geopolitical context of East Jerusalem and historic Palestine more broadly. Decision 3790, also referred to as the “Plan to Reduce Socioeconomic Gaps in East Jerusalem,” was declared following the 2018 Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People, which confirmed that the Israeli state is a state for the Jewish people above all.21 While an extreme right-wing government was in power in Israel in 2018, negotiations between the Palestinians and the Israelis have been nonexistent for a long time, particularly with regard to Jerusalem. Within this context, and despite the disputed status of the city, the Israeli government has continually strengthened its rule over East Jerusalem and created irreversible facts on the ground to ensure permanent Israeli control and Judaization of the city (see Settlements; The Separation Wall). Thus, a critical component of Decision 3790 is its objective to consolidate Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem, in particular the development of the Old City and the Holy Basin.

Potential Impact of Decision 3790 on Palestinian Jerusalemites

Theoretically, LSR in East Jerusalem should benefit Palestinians individually and collectively. Indeed, it is long overdue to secure their rights to the land according to a formal and modern land regime. LSR also stimulates development and facilitates the conversion of “dead,” stagnant capital into "living” and “flowing” capital.

That being said, given the existing political context of Israel’s military occupation of East Jerusalem, the reality is that for Palestinian Jerusalemites, land registration also has the potential to create serious problems. Perhaps most conspicuously, the LSR process furthers the Israelization and Judaization of the land by legitimizing the Israeli state’s control over it. During the LSR process, landowners are required by law to provide evidence to substantiate their claim to ownership over a piece of land. This process has two potential dangers: (1) It opens a window of opportunity for Israeli Jewish settlers to claim land in the same way; (2) any land to which claims are indefensible or tenuous in the eyes of the Clerk of Settlement and the court will then be registered in the name of the State of Israel. So, landowners who enter the process in good faith may find themselves suddenly dispossessed.22

Moreover, the process of land registration will invariably turn up property that Israel considers “absentee.” Indeed, the Israeli Custodian of Absentee Property is part of the process, and once such property is identified, the Custodian will take possession of it, register it, and transfer it to the state. In addition, the current LSR initiative is meant to cover extensive swathes of land (around 26,300 dunums) that Israel confiscated in 1967 based on the 1943 Land (Acquisition for Public Purposes) Ordinance in order to subsequently register it as state land and build Israeli settlements upon it.23 In other words, based on the authorized outline and detailed plan for Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, all the land allocated for public use and public space (i.e., “green areas”) will be authorized by the Clerk of Settlement and the court for registration in the name of the Jerusalem municipality or the State of Israel.

Another complication for Palestinians is that LSR is extremely costly, posing economic risks to those who take part in the process. By law, every landowner has to pay a number of land taxes, such as taxes of purchase and taxes of betterment. This is in addition to the costs involved in preparing an application for the Table of Land Claims, which should be prepared by a team of professionals, including a lawyer and surveyor.24 Given that around 75 percent of the Palestinian population in East Jerusalem lives under the poverty line, entering into modern LSR places a potentially unmanageable financial burden on most Palestinians who reside in Jerusalem.25

Finally, within the Palestinian community, long-standing land disputes will likely erupt with land registration, causing disruption to social life. Indeed, once landowners register their land claims according to the Torrens title system, repressed but simmering intrafamilial tensions and conflicts will surface, altering the stability that has long been based on traditional norms and customary law, including the use of the traditional deeds registration system. The contradictions between customary laws and state laws in the context of occupation and scarcity of resources will inevitably lead to social unrest.

How should Palestinians prepare for the new LSR initiative?

Palestinians now face the dilemma of how to deal with Decision 3790 and the resumption of modern LSR in East Jerusalem. Can they benefit from it? If so, how? To respond to these questions, more research, discussion, and analysis are needed around the implications and consequences of the new Israeli policy on Palestinian Jerusalemites. Nonetheless, there are some preliminary directions Palestinians and their leadership can take throughout this process.

To start, and given its limited authority in East Jerusalem, the Palestinian Land Authority must at least offer guidance to Palestinians in East Jerusalem on how to respond to the Israeli decision to resume modern LSR. For example, it can offer insight and advice from its experiences with land issues in the remainder of the West Bank. Moreover, and given that the new LSR initiative requires landowner participation, Palestinians can stall the process by requesting further information and time. Indeed, according to Decision 3790, Israeli representatives have to explain the benefit of the new LSR to Palestinian landowners.26

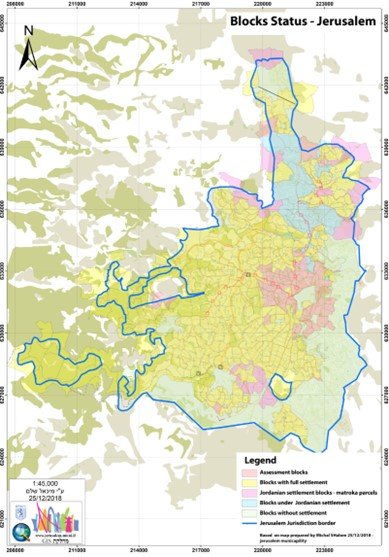

Another point worth considering is that according to Article 6 of Decision 3790, the LSR initiative actually includes most of East Jerusalem (see Figure 1). This area has different kinds of blocks, various land uses and planning allocations, and different classifications of land registration, including land that has no settlement or land that is at different stages of the settlement process (see The Complex and Unresolved Status of Land in East Jerusalem).

It is therefore imperative for the Palestinian Land Authority and interested Palestinian parties to undertake a comprehensive evaluation of how to deal with each block’s particular situation and classification. For instance:

- The Palestinian Land Authority must work with the Jordanian government to obtain data to process Jordanian blocks that have already passed the Table of Land Claims. Processing these blocks first establishes the precedent for other blocks across East Jerusalem. That is, within each block or larger area, Palestinian landowners should organize to prepare a professional cadastral map presenting existing, accepted distribution of parcels according to customary law and habits, along with a list of the owners. Once all landowners and mukhtars have signed it, this map should be submitted to the Clerk of Settlement and the court. In theory, Israel should automatically authorize this.

- The process of LSR should begin with rural, uncultivated lands so as to assert Palestinian claims to the city in a simpler, more cost-effective manner. This would lay the foundations, and deepen Palestinians’ political and legal expertise, in order to then pursue more complex lands, including in developed or urban areas.

Conclusion

Land lies at the core of the conflict between Zionism and the Palestinians, particularly in East Jerusalem. The Israeli state wields its power through a sophisticated matrix of laws and bureaucratic procedures, including those pertaining to LSR, to consolidate its control over the land. Indeed, land ownership is not just an instrument for possible development; rather, it is part of Israel’s strategic goals vis-à-vis colonizing Palestine. Therefore, in this context, LSR cannot be separated from the political context and viewed only as a routine matter of ensuring civic order. Israel has decided to resume land settlement in East Jerusalem after a 51-year freeze in order to unilaterally exercise sovereignty over an area it occupies illegally, and whose ultimate status has been disputed since 1967. The prevailing assumption has been that the disputed status of Jerusalem would be determined through negotiations between both parties who lay claim to the city: Israel and the Palestinians. But Decision 3790 makes clear that the Israeli government is no longer waiting for such a moment, and that it has thus taken it upon itself to decide that East Jerusalem will remain under Israeli control.

Granted, Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem may in theory also benefit from completing a modern LSR process, should they manage to succeed at proving their claims of land ownership.27 Once it is complete, anyone claiming ownership of the land can file a claim with the Clerk of Settlement. If conflicting claims are received, the proceedings will be referred to the court for decision, as required by law. And since Israel has thus far not allocated sufficient resources to implement Decision 3790, Palestinians in East Jerusalem have an opportunity to strategize how to respond proactively rather than reactively. Indeed, Palestinian Jerusalemites must strategize how to protect their lands and themselves once LSR gets fully underway in the near future.

Contributors

Editors: Nadim Bawalsa and Kate Rouhana, Jerusalem Story

Notes

The Free Dictionary, s.v. “Torrens Title System.”

Ronet Lven-Shnor, “Privatization, Separation and Discrimination: The Movements of the Order of Rights in Real Estate in East Jerusalem” [in Hebrew], Eyone Meshbat [Legal theory], no. 34 (2011): 183–238.

International Crisis Group, “Reversing Israel’s Deepening Annexation of Occupied East Jerusalem,” 2019.

Interview with Mr. Ezadeen El-Saad, the Jerusalem Intercultural Center, March 16, 2020.

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, “Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook, 2019” [in Hebrew].

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, “Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook, 2019.”

Calculated from data collected from Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, “Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook, 2019.”

Calculated from data collected from the 2018 budget of the Jerusalem municipality.

Ma’ayan Nasher, “Illegal Building, Bloodshed, Conflict, and Two Billion Shekels per Year: The Price of Non-registration of Land in East Jerusalem” [in Hebrew], Jerusalem Institute for Policy Studies, 2018.

Nasher, “Illegal Building.”

Nasher, “Illegal Building.”

Hernando de Soto, “Citadels of Dead Capital,” Reason, May 2001; Hernando de Soto, “Law and Property Outside the West: A Few New Ideas about Fighting Poverty,” Forum for Development Studies 29, no. 2 (2011): 349–61.

Government of Israel, “Government Decisions: Reducing Socio-economic Disparities and Economic Development in East Jerusalem,” May 13, 2018.

Ephraim Lavie, Sason Hadad, and Meir Elran, “Israel’s Plan to Reduce Socioeconomic Gaps in East Jerusalem,” Strategic Assessment 21, no. 3 (2018): 9–21; Arutz Sheva Staff, “Strengthening Sovereignty in East Jerusalem,” Israel National News, May 13, 2018.

Government of Israel, “Government Decisions.”

Arutz Sheva Staff, “Strengthening Sovereignty.”

International Crisis Group, “Reversing Israel’s Deepening Annexation.”

Arutz Sheva Staff, “Strengthening Sovereignty” (emphasis added).

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, “Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook, 2019”; Ir Amim, “The State of Education in East Jerusalem: Budgetary Discrimination and National Identity,” 2018; report by the Knesset’s Center for Research and Information, “Schools in Arab Education in East Jerusalem Teaching Palestinian Curricula,” April 12, 2019.

International Crisis Group, “Reversing Israel’s Deepening Annexation.”

Reference pending.

Lven-Shnor, “Privatization, Separation, and Discrimination.”

Based on interviews conducted with various landowners, lawyers, surveyors, engineers, and planners involved in East Jerusalem development.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, “East Jerusalem – Facts and Figures, 2021,” May 10, 2021.

Interview with El-Saad.

Arutz Sheva Staff, “Strengthening Sovereignty.”