Abowd argues that controlling space is a colonial necessity. As an example, since its creation in 1948, Israel has continually ensured that Jerusalem is inaccessible to most Palestinians in the remainder of the West Bank and Gaza, and across the diaspora. The author spoke with Palestinians and Israelis who held the belief that the two groups must be kept apart to avoid tensions. This belief is useful for a state whose only endgame is to maintain perpetual domination, but it is a myth. As the many stories recounted in chapter 2, “Diverse Absences: Reading Colonial Landscapes Old and New,” tell us, prior to 1948, Palestinian Jews, Muslims, and Christians lived relatively harmoniously in the city’s western neighborhoods of Musrara, Talbiyya, and Qatamon; people visited and celebrated together and patronized one another’s businesses (see The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before East and West). During the British Mandate, both groups were under British rule.

After 1948, however, and with the exile of over 70,000 of the city’s Muslim and Christian Palestinians in the wake of the establishment of the State of Israel, the relationship between Jerusalem’s Jews, Christians, and Muslims was radically altered. They were literally divided between a Jewish “West” and a Palestinian “East” (see The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before East and West). The situation grew more dire with Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967. Since then, Israel has sought to maintain its grip over the city through any means, including by demonizing Palestinians and restricting their access to, and mobility in, the city through implementing segregationist policies banning them from many spaces (see The Separation Wall and Closure and Access to Jerusalem).

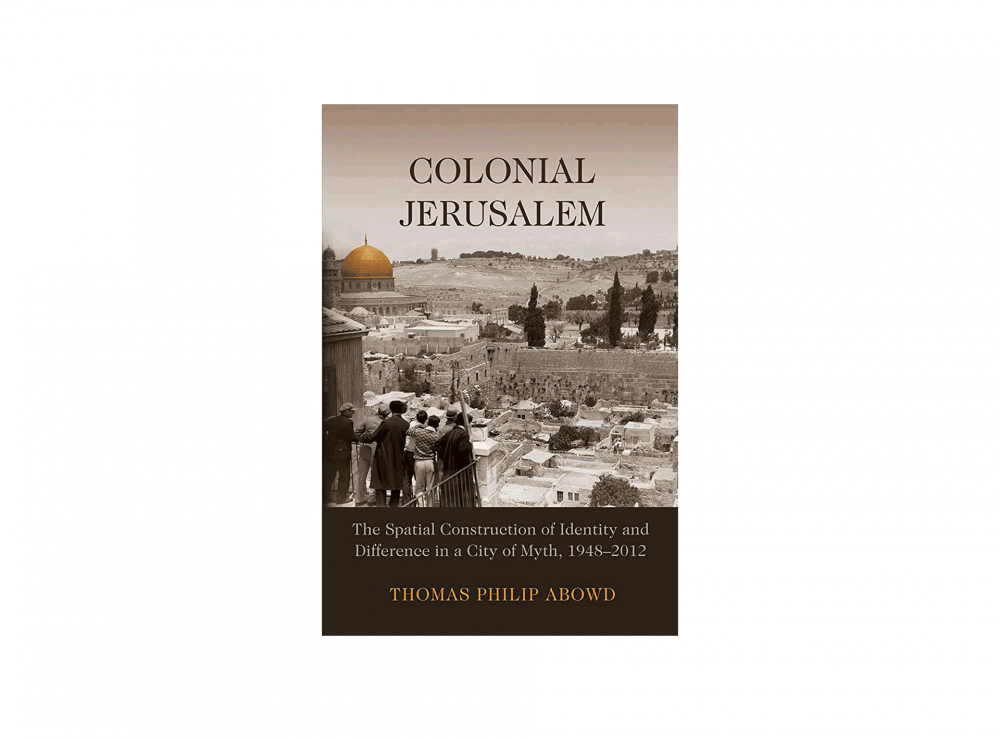

Abowd posits that no city has the “religious and symbolic potency”3 of Jerusalem. For that reason, it is instructive to study Jerusalem as a microcosm of the Zionist project, which uses the Bible to achieve colonial aims. Indeed, in Israel, the Bible and the stories it tells are taught as historical fact. As founding myths go, one that claims to be inspired by God’s will is hard to beat. In Jerusalem, as Abowd amply documents, Israel’s colonial machinery moves furiously and relentlessly to uproot the old and create facts on the ground, exploiting religious mythology in the process.

But sometimes, the old cannot be erased so easily, and in some cases, the colonizer might not want to get rid of it. Abowd describes these unruly facts that refuse to bend to the colonial narrative, such as old Palestinian homes. In chapters 2 and 3, he explores neighborhoods that still have their elegant old Palestinian homes, with a particular focus on Talbiyya, and describes what became of them in what was named West Jerusalem after 1948, upon the permanent exile of its original Palestinian inhabitants. Israel took several legal and demographic measures to orchestrate their transferal to the state (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property in Jerusalem) in order to secure them as Jewish properties that would serve state purposes and house Jews, often new immigrants. Many Palestinian homes became the residences of Israeli presidents, prime ministers, governmental offices, institutions, and so on, foreclosing the possibility of ever returning them to their rightful Palestinian owners.