Introduction

Credit:

Wikimedia

“These Are Our Homes”: Visiting West Jerusalem’s Neighborhoods with Ibrahim Matar

Snapshot

In 1948, tens of thousands of Palestinian Jerusalemite families lost their homes, businesses, and lands during the establishment of Israel. Even now, they preserve and cherish their memories and attachment to their homes.

This series introduces three Palestinian Jerusalemites—Ibrahim Matar, Huda Imam, and Munir Qleibo—who share perspectives about the West Jerusalem neighborhoods that Israel banned Palestinians from returning to after 1948, to educate people about the history of their families’ and friends’ homes, now inhabited by Israeli Jews. Part 1 of a three-part series. View Part 2 (Huda Imam) here and Part 3 (Mounir Kleibo) here.

“All these houses were Palestinian homes,”1 economist and author Ibrahim Matar tells a small group of friends during a walkabout in West Jerusalem on June 10, 2023.

Born and raised in Jerusalem, Matar shares accounts about Jerusalem’s middle class before the Nakba while pointing out the gracious houses one sees throughout the West Jerusalem neighborhoods Talbiyya, al-Baq‘a, and Qatamon—neighborhoods that were Palestinian before Israel’s establishment in 1948. He notes how these homes are identifiable by their distinctive architecture and are in fact Palestinian properties confiscated by the state and given to Jews.

Born in 1943, Matar was the founder and chairman of the Department of Business and Economics at Bethlehem University and was later the senior program officer with the Italian Cooperation Office of the Italian Consulate General in Jerusalem. After his retirement, he decided that he had a duty and responsibility to convey to others the effects of the traumatic wars of 1948 and 1967 on Palestinian families, as he learned them from loved ones and also recollected from stories he heard during his childhood.

Almost 80 years old, he has made it his mission to record the stories of Palestinians in Jerusalem who lost their homes in West Jerusalem—his friends, acquaintances, and others. Matar credits his late mother-in-law, Margueritte Nakhleh Catan Farah, for making him aware of the ordeal of Palestinian families living in the area called the New City, which Israel seized and then renamed West Jerusalem after the war, in 1948. She witnessed the forcible expulsion of friends, neighbors, and family members by the Jewish forces in Talbiyya. She herself had fled for temporary safety during the 1948 War. She was never able to return to her home (see The West Side Story, Part 4: The Erasure of the New City and Its Transformation into Jewish West Jerusalem).

“Theft of Palestinian Properties in West and East Jerusalem”

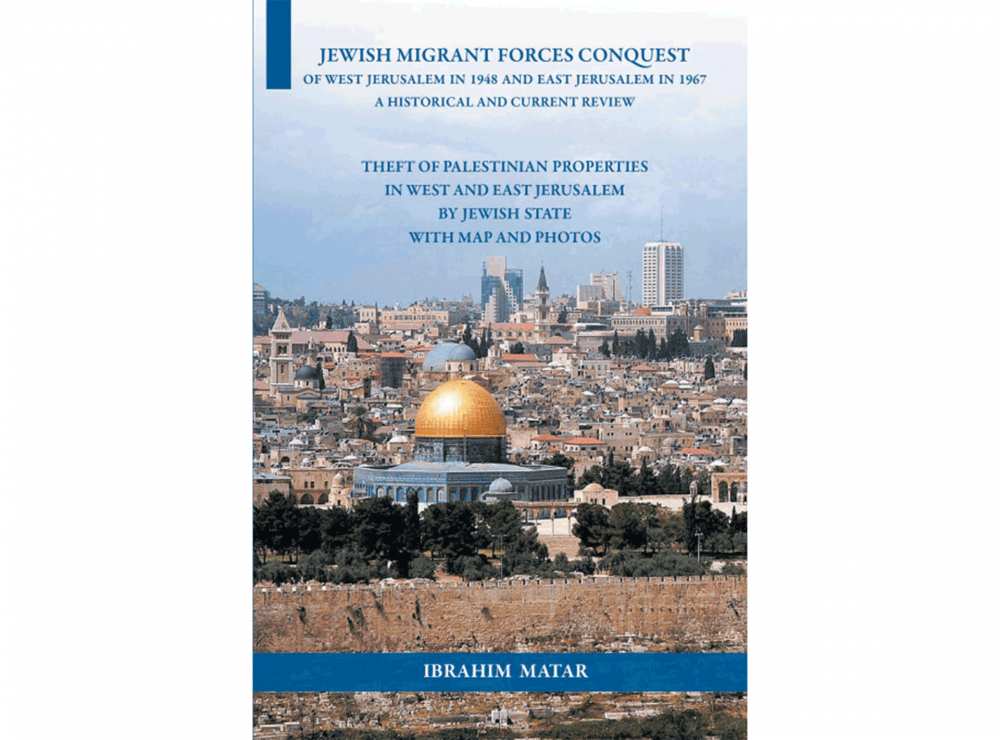

Accounts of property confiscation, told to Matar by others, led him to write about the private properties of Palestinian families that “the Jewish State proceeded to steal.” His book Jewish Migrant Forces’ Conquest of West Jerusalem in 1948 and East Jerusalem in 1967—A Current and Historical Review: Theft of Palestinian Properties in West and East Jerusalem by the Jewish State was published by Newman Springs Publishing in 2022. Its purpose is described on the cover as being “to prove that the bulk of the properties in Jerusalem belong to the native Palestinian citizens of Jerusalem.”

In the book, Matar delves into some of detail about the Absentees’ Property Law—1950 (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property in Jerusalem).

Matar explains that the law provided the basis for Israel to confiscate the homes and other property of Palestinians who fled (temporarily, they thought) from the violence in their neighborhoods in 1948. When the hostilities ended, Israel passed laws that banned them from returning (see The West Side Story).

He recounts that Palestinians owned villas, apartments, houses, and commercial properties in various areas of Jerusalem, including Upper and Lower Baq‘a, Qatamon, the Greek Colony, the Nammariyya neighborhood, the Dajaniyya neighborhood, Abu Thawr, Talbiyya, Jurat al-‘Inab (outside Jaffa Gate), and Musrara.2 Properties in these neighborhoods, he explains, were seized by the Custodian of Absentee Property in the Israeli Ministry of Finance and sold or rented exclusively to Jews. The new Jewish occupants of these confiscated homes walked into fully (and often expensively) furnished homes; the rightful owners, who were prevented from returning and reclaiming their property, were often left destitute.

Escorted Walkabout

Matar walks a small group of friends around West Jerusalem, sharing details about homes and neighborhoods as they go. He is eager to share what he knows and has learned from his research for the book.

In Upper Baq‘a, Matar stops along the way and tells the group: “You must know al-Wa‘ri family, the ones known for their great shawarma place close by al-Zahra Street. They had their property right here. This area is named after them; al-Wa‘riyya neighborhood. All this property was seized by the Custodian of Absentee Property and sold [or given] to Jews.”

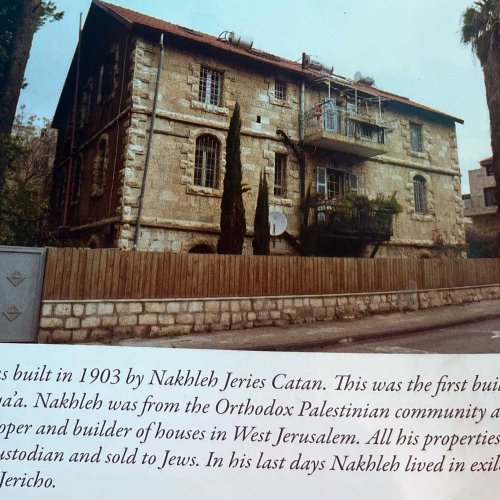

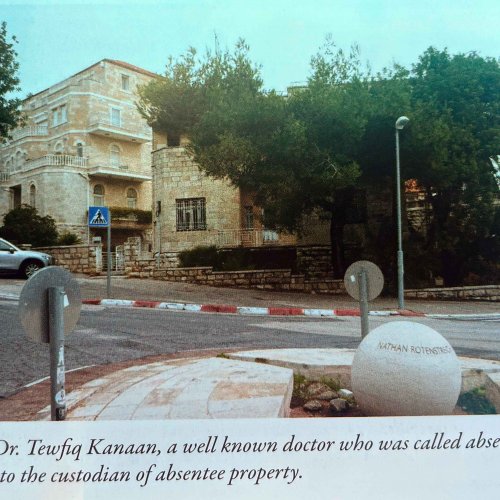

He mentions names of Palestinians, some well-known, others less so. The pioneering doctor Tawfiq Canaan lost his home in Talbiyya; perhaps as valuable as the home was his extensive personal library and three manuscripts he was readying for publication. Meanwhile, the real estate developer Nakhleh Catan was the first Palestinian to build a home in Upper Baq‘a (in 1903), which was likewise seized by Israel. After the war, Catan resettled in Jericho.

Villa Harun al-Rashid

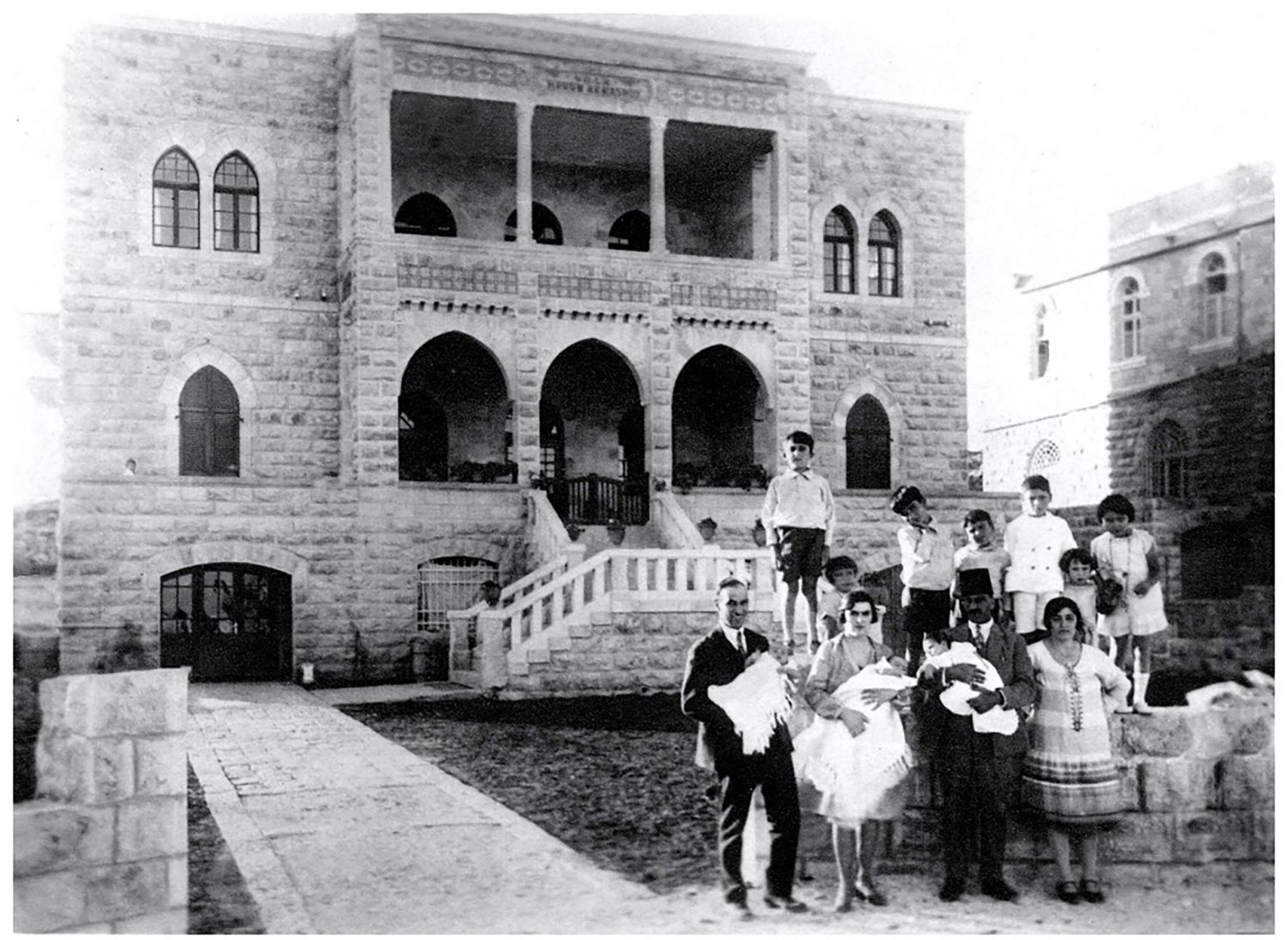

Matar stops in front of the Bisharat villa in Talbiyya named “Villa Harun al-Rashid” (“in honour of the celebrated Muslim caliph renowned for his passion for justice, generosity, and love of learning”), which was built by Hanna Bisharat in the Talbiyya neighborhood of the New City, the same neighborhood where Edward Said’s family lived, in 1926 and was generally considered to be the most beautiful house in Jerusalem.

During the 1948 War, the empty Villa Harun al-Rashid was selected by the Zionist forces for its commanding height and views as a military lookout; the British gave them the keys. Later it was divided into flats and one of them was inhabited by Golda Meir, later Israel’s foreign minister who famously said, “the Palestinians did not exist.” She ordered the name of the villa sandblasted off, but apparently this was not thorough enough to erase it. Later, Bisharat visited the home and found it occupied by Justice Zvi Berenson of the Israeli Supreme Court, one of the drafters of the Declaration of Independence, whose wife’s first words upon opening the door were, “the family never lived here.”3

Its confiscation, and the family’s attempt to reclaim it, is the subject of Palestinian filmmaker Sahera Dirbas’s documentary On the Doorstep (2018–19). In the film, Bisharat’s granddaughter Valerie, 21, travels across the world to locate and see her ancestral house and weeps when she enters it and comes face to face with Gisele Arazi, 96, the current Israeli Jewish owner.

Naming Names

Much as Dirbas did in her previous documentary Stranger in My Home (2007), where she highlighted the stories of dispossession of Jerusalemite families (including the Assali, Barakat, Khoury, Jareedi, Habash, Baramki, Sakakini, and Bisharat families), Matar makes it a point to name names. By hearing about the homes of specific families that were seized by Israel, readers and listeners understand that the loss was experienced by specific people, and not just a vague collective.

“These are the lost homes of the Habash family . . . the Dajanis . . . the Catans . . . This is the crime of the century,” Matar sighs.

Acknowledging the names and stories of individual Jerusalemites makes the collective loss that Palestinians continue to experience more personal—real people lost their homes. “The Palestinians never abandoned their homes,” he stresses, “But this law allowed the Israeli government to declare as ‘abandoned’ the homes that Palestinians were not allowed to return to, which were then quickly designated as state property. They [the Israelis] made it look legal, but it’s clearly theft.”

Matar’s book can be purchased at bookstores or online at the Apple iBooks Store, ReaderHouse, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.

Read Part 2 of this series here.

Notes

All quotations from Ibrahim Matar in this piece were captured during the walkabout of the West Jerusalem neighborhoods on June 10, 2023, described here.

For a comprehensive study of these and other Palestinian neighborhoods in Jerusalem before 1948, see Salim Tamari, ed., Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighborhoods and Their Fate in the War, 2nd ed. (Jerusalem: The Institute for Palestine Studies and Badil Resource Center, 2022). Also available in Arabic.

George Bisharat, “The Family Never Lived Here,” Haaretz, January 2, 2004.