Tawfiq Canaan (b. September 24, 1882, in Beit Jala) was a pioneering Palestinian physician, medical researcher, scholar, and prolific writer. He became especially known for his collections of amulets and his groundbreaking ethnographic work on Palestinian folklore and superstition.

Childhood and Education

Tawfiq Canaan was born on September 24, 1882, in Beit Jala.1 His parents, Bechara Canaan and Katharina Khairallah, were both Lutheran; he was their second child of six—in birth order: Lydia, Tawfiq, Wadi’, Badra, Hanna, and Nagib. His childhood was largely influenced by German Protestants, proponents of a minority denomination in those days.

Canaan’s father was an influential figure in society: Educated in Jerusalem, he became a pastor in 1891 for the German Protestant Palestine Mission and was the first native Arab Lutheran pastor in Palestine. He founded institutions in Beit Jala: the first Lutheran church in the town (1882), a coeducational school there, and the first Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Jerusalem (1878). He was also one of the first to learn to play the organ, which he in turn taught his children.

The pastor often took his children to historical sites around Beit Jala and on walks in the vicinity. Through his father’s work and family excursions, Canaan became acquainted with different segments of Palestinian society. His love of Palestinian people and culture originated with these outings, as he later related:

We used to go with my father on short and long trips all over the country in order to get acquainted with the country and the people. This continuous contact with the people nurtured in all of us, and particularly in me, love for the country and the people. This feeling of belonging and unshaken loyalty remained with me till this day.2

He was especially fascinated with the Palestinian fellahin and their traditions, which would have a great impact on his career in later years. Again, he attributed this to his father:

During summer vacation, he arranged for long tours to Tannur, Battir, Bayt Sahur, al-‘Arrub, etc., where we rode on donkeys. Such tours planted in me the love for country and the fallah. In the summer, father leased a vineyard. We had to get up early and walk to the field and bring figs and grapes for the day. These had to be ready for breakfast. It was a nice custom to have, while carrying the fruits home, acquaintances whom we met on our way would help themselves. In most afternoons the whole family went again to the vineyard to spend one hour in the fresh air. Nothing was lost of the fruit we brought home. Berries which were not suitable for eating were pressed for vinegar. We made our own wine; as we had no wine press, the grapes were crushed by treading upon the vats after washing all our feet.3

Canaan had a Protestant education, starting first in Beit Jala for primary school and then at age 11, moving to the (German) Schneller School in Jerusalem, as his father had,4 where he completed high school.

In the winter of 1899, he enrolled in the American University of Beirut (then the Syrian Protestant College) to study medicine. Soon after, his father died of pneumonia back in Palestine. All churches in Beit Jala rang their bells to signal mourning of and respect for Bechara Canaan, who had been an influential figure in society. His passing was particularly difficult for his son Tawfiq, who, although just a student, had to cover his own living expenses from that point on. (He was given a scholarship to cover tuition.) He supported himself by offering private language lessons and working at the university.

Since English had not been taught at Schneller, Canaan had to start in the lowest class, as the language of instruction was English. But his diligent application to his studies meant he soon caught up sufficiently to skip his freshman year altogether and enter as a sophomore. He was always the first in his class. Apparently he had an aptitude for dissection, as he wrote in his memoir:

In the practical work in anatomy, that is, in the dissection of human bodies, I had the greater chance of doing my part and that of many students who did not care to do their work. In this way I had the exceptional opportunity to thoroughly study anatomy. On vacation, I anesthetized cats and dissected them, thus studying anatomy in a living animal. On commencement day I received honors in anatomy, chemistry, physiology, histology, internal medicine, surgery, ophthalmology, dermatology, therapeutics, ear-nose-throat diseases, and hygiene.5

In 1905, Canaan graduated with distinction as a medical doctor.

Launch of a Stellar Medical Career

After graduation, in the summer of 1905, Canaan hastened back to Jerusalem and worked as an assistant doctor at the German (Kaiserwerth) Deaconess Hospital there under the supervision of a surgeon, the hospital director Dr. Gruendorf. He later shared, “My decision to go to Jerusalem and to work in the German hospital decided my whole future. I never was sorry for this decision.”6

The work was formative in introducing him to another one of his passions:

The work in the hospital, especially my close connection with the patients, gave me great experience with the folklore of the country. This interested me so much that I began to enquire about the amulets, which most of the patients carried: how they were thought to act, how they have to be carried, who makes them, etc. All of this information was put on record. This was the stimulus which made me so interested in the customs and beliefs of the people and which allowed me to write many articles and books.7

Despite Canaan’s hard work and popularity among his patients, the hospital broke his contract and replaced him with by a young German doctor a little over a year later. He later wrote, “I was deeply hurt, not only because my contract was broken without any cause, but for the preference of a European to an Arab.”8

He opened a private practice, which soon was profitable enough to support him. Alongside his practice, he was engaged by the London Jewish Society to work at their hospital (also known as the English Hospital) and was subsequently hired by the new Shaare Tzedek Medical Center, the first Jewish hospital in Jerusalem, which at that point was only four years old. Soon, he became its director. These experiences opened opportunities to treat Jewish patients as well.

By 1910, his reputation had grown, and he assumed additional responsibilities. The then mayor of Jerusalem, Hussein al-Husseini, appointed Canaan municipality doctor. About this role, he wrote in his memoirs:

My duties were to inspect the sanitary conditions of the city, to treat the prisoners and to act as the medico-legal advisor. Every day I made a round in one of the quarters of the city and reported officially to the mayor. The sanitary inspector who accompanied me promised on every occasion to do what I proposed, but he rarely did it. The municipality had its own difficulties; I could not remain more than 1 3/4 years in this position, as my private work increased so much that I had to buy a horse.9

Between 1906 and 1910, Canaan conducted research on the science of germs, in addition to his clinical work. In 1912, he went to Germany to specialize in microscopy bacteriology and tropical diseases, with an emphasis on tuberculosis.

In January 1912, Canaan married Margot Eilender, whose father was a German importer. The couple built their home in the Musrara neighborhood, close to Bab al-Amud, in 1913, and had four children: Yasma, Theo, Nada, and Leila there. Also in that family house, Canaan opened the first and the only Arab clinic in Jerusalem.

Curing Leprosy, Building Cultural Institutions, and Composing Music

Canaan’s medical laboratory research led to his appointment, in 1913, as director of the malaria section at the International Health Bureau/Hygienic Institute (an international center for medical research and microscopic testing) in Jerusalem.

When World War I erupted, Canaan was drafted into the Ottoman army. He was appointed director of the malaria branch of the International Health Bureau, a world center for research. He also served as head of the laboratories on the Sinai Front. In these capacities, he traveled widely among many Arab cities, including throughout Palestine as well as Damascus, Amman, and Aleppo. During his wartime travels, he continued to add to his growing collection of amulets (good luck charms) from far-flung places. He also contracted cholera and typhus and survived both.

“By the end of the First World War,” Canaan wrote in his memoirs, “I was recognized as the best internal diseases physician in the country.”10 Among other achievements, Canaan had developed a reputation as an authority on leprosy (today called Hansen’s disease, a chronic, slow-developing bacterial infection spread through close contact that causes progressive and permanent damage to the skin, nerves, limbs, and eyes).

In 1919, back in Jerusalem in the New City neighborhood of Talbiyya, he became head of the Leper Home, built by the German Protestant Moravian Church in 1867. This was the only leprosy hospital in Palestine, Syria, and Transjordan. (After World War II, it was moved to Silwan just outside the Old City of Jerusalem and then to northward to Ramallah in West Bank after Israel occupied the remainder of Palestine in 1967.) At the time, leprosy was considered incurable, yet Canaan’s study of bacteriology and microscopic examination made it possible to cure many patients and had a major contribution to eradicating leprosy in Palestine. Indeed he wrote, “Every case which had some hope of recovery, regardless of how small, was treated with determination at the Leprosy Hospital.”11

Canaan continued to work at the Leper Home (now Hansen House) and in 1919, after the war, became its director, a position he retained until the end of the British Mandate.

Between World Wars I and II, he organized and led the Jerusalem Arab Medical Association. Later, he organized branches in Haifa, Jaffa, Nablus, and Gaza, and in August 1944, founded the Palestine Arab Medical Association. In the 1940s, he was elected its first president, a title he held until the association was dissolved in 1948. He also served as member of the editorial board of its journal, which had significant contributions in Arabic and English and provided medical aid to Palestinians. The Jerusalem Association remained in existence, with Canaan at its helm, after the war; he held that role until 1954.

From 1924 to 1940, Canaan was chief of the German Hospital’s internal medicine division. By the 1930s, his reputation had spread throughout the region: Among his patients were Sherif Hussein of Mecca and the Palestinian fighter Abu Jilda, who sustained a bullet injury during the 1936–39 revolt.

Nurturing Jerusalem: Culture and Society

It is noteworthy that this busy physician made major contributions to the cultural life of Jerusalem. In 1920, he became secretary of the newly founded Palestine Oriental Society, established to publish research about the “Orient.” He served as editor of their journal until 1939. He also was deeply invested in the YMCA in the New City, in what later became West Jerusalem, starting as a member in 1908 and becoming president for the first time in 1913–14 and a second time again later. (His father had served it as president for three terms.) After his retirement, he was elected honorary president for life.

The YMCA was close to his heart: He deeply enjoyed watching it take root and grow. In his memoirs, he called it “a great blessing for the country” and said that “our beloved institution was our pride as its blessings shown [sic; shone] on Jerusalem and its surroundings.”12

Canaan was also a musician: He composed almost 100 short musical pieces, many of which were played in the YMCA concerts.

Healing Medicine and Culture: Palestinian Folklore

The significance of Canaan’s work in documenting Palestinian folklore cannot be overstated. He was drawn to “popular medicine, the spiritual beliefs among peasants, the demonology, the relevant rituals that confer protection and blessings on the village and the superstition.”13 He developed a passion for collecting objects that his patients, particularly peasants, used to cure diseases and which they believed had healing powers. Fascinated with popular culture, he deciphered traditions that spanned biblical, Canaanite, Arabic, Nabatean, and peasant traditions. He particularly focused on fallahi practices, which people believed in, although they were disconnected from Islam and scientific medicine. In this way, Canaan became an ethnographer and anthropologist of the native culture: He gathered and labeled more than 1,400 amulets, talismans, and various other objects that related to popular medicine and folk practices: jewelry, glass beads, stones, certificates, offerings, vessels, ceramic dishes, fear cups, and other items.

In 1995, Birzeit University’s Founding Committee for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (chaired by the Palestinian artist Vera Tamari) established “The Tawfik Canaan Collection of Palestinian Amulets.”

In October 1998, Birzeit University had an exhibition that featured 200 items from Canaan’s 1,400-piece collection (gathered between 1905 and 1947), which had become the largest from Palestine. The collection is now permanently housed in the Canaan Collection at Birzeit University Library, providing a rich heritage of folk medicine, and demonstrating the magic manifestations of popular beliefs and practices.

An example of what Canaan captured in those collections was displayed in the exhibit “Ya kafi, ya shafi” (O Protector, O Healer). The expression was used

as a way to address God, but also a prophet or a walī, and it is used when a person seeks protection and healing. This expression . . . showed the interest in addressing the healing and protective qualities of the amulets, aspects that were central in Taufiq Canaan’s own approach to the amulets.14

Palestinian curator and museum registrar of the Palestinian museum Baha’ al-Ju’beh notes the importance of Canaan as a researcher of Palestinian popular heritage:

[He] probed and asked questions concerning the value of amulets and talismans as a source of knowledge in interpreting the traditions and beliefs of his people. His writings in this field are an indispensable reference for researchers and all those interested in Palestinian heritage.15

Arrest

Canaan was also politically engaged and would pay the price (in 1939) of expressing his opposition of the Balfour Declaration. Ironically, Canaan had been previously thrown in jail in Nablus as a Christian who was assumed to have been pro-British; yet when the British took over, he expressed his viewpoints with no inhibitions and paid a price for that.

As a result of his hostility to Zionism and the British Mandate, the British authorities blacklisted him and, on September 3, 1939, they arrested him. His sister Badra and his wife, Margot, were also arrested on the premise of political activism, as they had helped found the Arab Women’s Committee in Jerusalem in 1934, which called for civil disobedience and the continuation of the Arab strike of 1936. (Margot would be arrested again during World War II as a German national in a British-administered territory.)

Wartime: Service, Losses, and Aftermath

In 1947, the Palestine Arab Medical Association was given four area hospitals to run, an accomplishment that Canaan saw as a “great triumph.” These included two in Jerusalem—the government hospital in the Russian Complex (al-Moskobiyya), the Austrian Hospice in Beit Safafa—and two mental hospitals in Bethlehem. Soon after, the war broke out and Canaan found himself at ground zero, running hospitals directly in the war zone.

Describing the wartime situation later in his memoirs, he wrote:

The Austrian Hospice hospital worked very hard; at times the doctors had to work through the night to treat the wounded that flocked from all directions. We had at times about two hundred patients—some were placed on the floor—and we did not have enough physicians since most had run away just before the hostilities began. The hospital was bombed a few times by the Jews and I complained directly to Count Bernadotte. In the first few weeks of running the hospital we became short in provisions and petrol. I used the radio to announce our great need and asked for donations. Soon it seemed the whole population began to come bringing what they could spare, and through their donations we were able to continue.16

In his memoirs, Canaan relays that the hospitals were bombarded directly by Zionist forces several times, and he therefore appealed to Count Bernadotte directly in writing in early August 1948 to make it stop. Bernadotte committed to do everything in his power to make the attacks stop, even if it meant taking it up with the Security Council. A few short weeks later, he was assassinated by the Zionist terrorist organization Lehi.

The war also came to the Leper Home in Talbiyya, where Canaan was still working, insofar as when the area was declared part of Israel, the Arab patients and staff were forced to leave and relocate to another facility across the city in Silwan in Arab East Jerusalem. According to Palestinian sociologist Salim Tamari, this separation

marked one of those defining moments in the annals of Jerusalem and the Arab-Israeli conflict. In its absurdity, the event encapsulated the depth of the process of ethnic exclusion and demonisation after decades of conflict between Jews and Arabs, settlers and natives. It also signalled a turning point in which much of the intellectual debate, as well as popular sentiment, about the future direction of the country and its sense of nationhood began to crystallize around two separate and exclusive narratives of origin.17

In addition to his work in the hospitals, Canaan also arranged first aid stations in Jerusalem, which he had to oversee by walking among them regularly. (After the war, Canaan no longer had access to a car and had to walk to see his patients.) He noted, “The young men in these stations served without any remuneration and served well.”18

Decision to Stay

When war approached in 1948, Canaan made a critical decision:

In the third and fourth month of 1948, most physicians left Jerusalem—a very great shame. I, the oldest, decided not leave. My wife and I had no children with us. The girls were married and Theo lived in Beirut.19

Soon enough, war came to their own home:

As our house was in the firing zone, we decided to move. The Greek Orthodox convent gave us one furnished room. We carried a few things from home, hoping that we could soon return back.20

In this decision under duress of wartime, they faced the same plight as hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians in Jerusalem and the country at large at that perilous time.

Canaan later noted that he, a well-to-do world-renowned physician, only took 15 pounds with him when departing the house, so transient did he expect their move to be.21

Their house in Musrara received direct hits by the Zionist militias in February and May of 1948. His daughter later recalled:

Mother and father would go daily to the top of the Wall of Jerusalem to look at their home. They witnessed it being ransacked, together with the wonderful priceless library and manuscripts, which mother guarded jealously and with great pride. They saw mother’s Biedermeyer furniture being loaded into trucks and then their home being set on fire.22

Reflecting on this family Nakba, Canaan recounts:

A few days after we moved to the Greek Convent, our house caught fire. When I saw it at 8 p.m. my heart bled. I did not believe it and so I went to the Franciscan convent. Here the custodian led me and I saw how the whole ceiling and upper story were in flames.

Thus I had now no house, no furniture, no car and even the good sum of money which I had left there was lost. I was sorry for only a few hours and then I got over it and slowly forgot it. Although I took only fifteen Palestine pounds with me when I left my house, the Almighty helped me wonderfully and I had never to ask for help.23

As a result of the war, the Canaan family not only lost their money and cherished home (which caught fire and burned while they watched); they lost Canaan’s home clinic and their precious library, as well as Canaan’s personal manuscripts (three of them readied for publication), valuable collections of folklore material, including proverbs and fables, not all of which had been published, and 100 music compositions. During the 1948 War, he would lose the scores, together with his house, his clinic, and his valuable collections of folklore material, including proverbs and fables; at that point, only some of it had been published. In his memoir, he recalled:

My greatest loss was my not yet published book “Die arabische Frau v.d. Wiege bis zum Grab.” For this I had brought together an enormous amount of unpublished and new material. Nevertheless, I began to gather the material again and to note every custom I heard about. My collection of stories was never published. I had so many that in social settings I could tell one story after the other—for one and a half to two hours. Many were the same stories heard from the peasants about high moral teachings.

For my children I was able to write a few fables.24

His collection of amulets and icons survived, because he had given it to an international organization in the New City as a precaution.25

After their loss, the family had to cope and Canaan had to continue serving his community in the hardest of times. Their living conditions were sparse and cramped:

The four of us—my wife, sister, sister-in-law, and myself—lived in one room. It was our kitchen, sitting/dining/sleeping room and office for treating patients. But we were thankful for having a roof above our heads. It is a shame the LWF never thought of giving us any room in the Muristan [in the center of the Christian Quarter in the Old City]. Soon the monks of the Greek convent gave us a second room which served as a sleeping room for my sister and sister-in-law and an office for me during the day. My work during this period was very hard. I went twice daily to the Austrian Hospice hospital, and to the Convent of the Soeurs de Sion, where I had my office for the Jordanian Red Crescent and Red Cross.26

In 1949, he moved on from those hospitals to become head of the Lutheran World Federation’s medical department. In this capacity, he opened and ran four polyclinics, including one in Jerusalem. He also was instrumental in establishing important institutions, including the Augusta Victoria Hospital on the Mount of Olives in 1950. He served as its director until his very last days.

He retired at age 75 and devoted himself to writing his memoirs, which cover seven decades of Palestinian history.

Writings

Besides his brilliance in medicine, Canaan excelled in languages. He was fluent in Arabic, English, German, French, Hebrew, and Turkish. He wrote extensively, and authored several ethnographic works in English, Arabic, German, and Hebrew.

Canaan’s first published piece (reproduced in al-Muqtataf journal) was based on his valedictory speech at his graduation ceremony from the American University of Beirut (AUB) on June 28, 1905. He conducted more than 37 studies on tropical medicine, bacteriology, malaria, tuberculosis, leprosy, and other topics.

He would go on to publish more than 130 articles, and he wrote five books that ranged from subjects relating to religion (and the Bible), folklore, superstition, medical studies, architecture, archaeology, and agriculture.

He also wrote about the Palestine-Israel conflict and delivered many lectures on this subject. Two of his books were on the question of Palestine and focused on British imperialism and Zionism. Canaan also journaled and started to write his memoirs.

Honors and Awards

Canaan received numerous prestigious awards. In 1938, he received the decoration of the Red Cross at the German Deaconess Hospital. In 1955, he was awarded the Golden Cross of the Holy Sepulchre by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch. In 1957, he was honored with the Federal Republic of Germany’s Order of Merit in appreciation of his contributions to the German missionary institutions in Palestine. In 1958, he was awarded the golden medal award of the Medical Association of the AUB, delivered by Dr. Amin Majaj.

Canaan’s accomplishments continue to be celebrated to this day. In 2013, Dar al-Kalima’s international conference (held in Bethlehem) “Palestinian Identity in Relation to Time and Space” reset the stage for interest in the works of Canaan.

Death

Canaan died in the Augusta Victoria Hospital in Jerusalem on January 15, 1964. He was buried in the Evangelical Lutheran Cemetery in Bethlehem, near Beit Jala where he had spent his childhood. He was predeceased by his son Theo, the architect of the Hotel Ambassador in Jerusalem as well as the Jerusalem Cinema, who died prematurely in a worksite accident in Lebanon in September 1953.

Selected Works

Articles

“Haunted Springs and Water Demons in Palestine.” The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 1 (1920–21): 153–70.

“Byzantine Caravan Routes in the Negev.” The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 2 (1922): 139–44.

“Folklore of the Seasons in Palestine.” The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 3 (1923): 122–31.

“The Oriental Boil: An Epidemiological Study in Palestine.” Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 23, no. 1 (1929): 89–94.

“Unwritten Laws Affecting the Arab Women of Palestine.” Paper delivered on March 26, 1931, before the Anthropological and Ethnological Society of the American University, Beirut, 172–204.

“The Saqr Bedouin of Bisan.” The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 16 (1936): 21–32.

“The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans.” Berytus Archaeological Studies 4 (1937): 69–110.

“Topographical Studies in Leishmaniasis in Palestine.” Journal of the Palestinian Arab Medical Association 1 (1945): 4–12.

“Intestinal Parasites in Palestine.” J. Med. Liban 4, no. 3 (1951): 163–69.

“Superstition and Folklore about Bread.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (1962): 36–47.

Books

Aberglaube und Volksmedizin in Lande der Bibel. Hamburg: L. Friederichsen, 1914.

Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine. London: Luzac & Co., 1927.

Dämonenglaube im Lande der Bibel. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1929.

Studies in the Topography and Folklore of Petra. Jerusalem: Beyt-Ul-Makdes Press, 1930.

The Palestine Arab Cause. Jerusalem: Modern Press, 1936.

Sources

al-Ju’beh, Baha’. “Magic and Talismans: The Tawfiq Canaan Collection of Palestinian Amulets.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no.22/23 (2005): 103–8.

Beacebrocess. “Who Are the Palestinians? The Life and Times of Tawfiq Canaan.” YouTube. January 23, 2022.

Birzeit University. “Tawfik Canaan Palestinian Amulet Exhibition Opened at Birzeit University.” November 7, 1998.

Borgo, Melanie. “Tawfiq Canaan: The List of a Physician and the Palestinian History.” Memorie Originali, no. 2 (2013): 29–30.

Canaan, Taufiq. “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1: The Formative Years, 1882–1918.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 74 (2018): 14–29.

Canaan, Taufiq. “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 75 (2018): 132–43.

Garcia Probert, M. A. “Exploring the Life of Amulets in Palestine: From Healing and Protective Remedies to the Tawfik Canaan Collection of Palestinian Amulets.” PhD diss., Leiden University, 2021.

Hadidi, Subhi. “Tawfiq Canaan, a Christian who Defended Palestine’s Islamic Identity.” [In Arabic.] Al Jazeera. June 18, 2008.

Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. “Tawfiq Canaan.” Accessed December 11, 2022.

“Moravian Work in Jerusalem.” Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, no. 9, July 2006.

Nashef, Khaled. “Tawfik Canaan: His Life and Work.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 16 (2002): 12–26 .

Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs. “Canaan, Tawfiq (1882–1964).” Accessed December 13, 2022.

Raheb, Mitri. “Seven Decades of Palestinian History: An Introduction to Tawfiq Canaan’s Autobiography.” This Week in Palestine, no. 273 (2021): 16-23.

Tamari, Salim. “Lepers, Lunatics and Saints: The Nativist Ethnography of Tawfiq Canaan and His Jerusalem Circle.” Jerusalem Quarterly File (2004): 24–43.

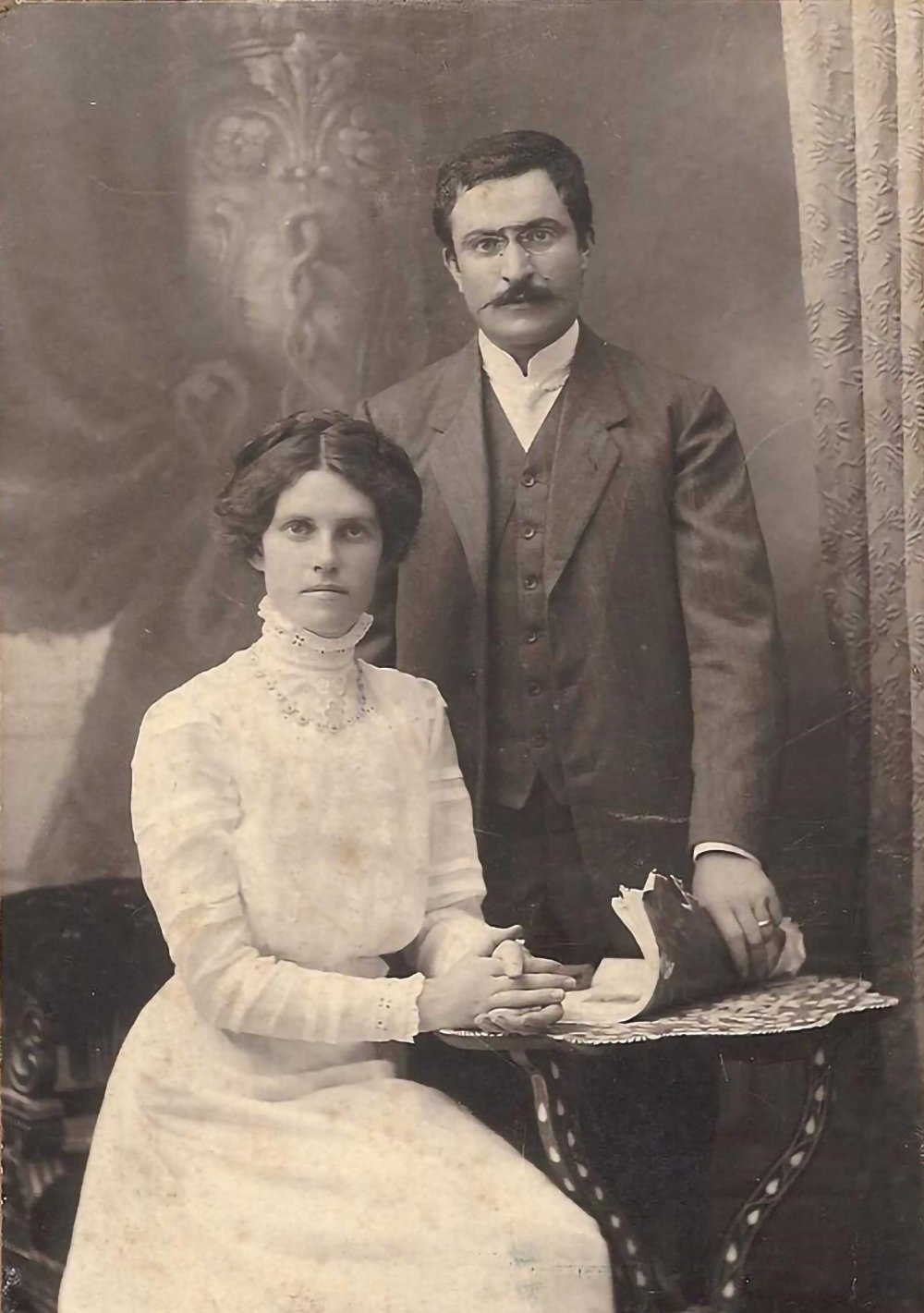

[Profile photo: G. Krikorian, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division [LC-DIG-ppmsca-18896] ]

Notes

He spelled his first name Taufiq, but it appears more commonly in the literature as Tawfiq.

Khaled Nashef, “Tawfik Canaan: His Life and Work,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 16 (2002): 14.

Taufiq Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1: The Formative Years, 1882–1918,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 74 (2018): 15.

Th school was founded by Rev. Johann Ludwig Schneller, born in Württemberg, Germany, as the Syrian Orphanage in Jerusalem in 1860. It later was renamed the Schneller School and had Muslim and Christian male students.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1,” 18.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1,” 18.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1,” 20.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1,” 20.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 1,” 23.

Taufiq Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 75 (2018): 132.

Cited in Nashef, “Tawfik Canaan,” 20.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 136–37.

Melanie Borgo, “Tawfiq Canaan: The List of a Physician and the Palestinian History,” Memorie Originali, no. 2 (2013): 29.

M. A. Garcia Probert, “Exploring the Life of Amulets in Palestine: From Healing and Protective Remedies to the Tawfik Canaan Collection of Palestinian Amulets,” PhD diss., University of Leiden, 2021, 189.

Baha’ al-Ju‘beh, “Magic and Talismans: The Tawfiq Canaan Collection of Palestinian Amulets,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 22/23 (2005): 103.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 133–34.

Salim Tamari, “Lepers, Lunatics and Saints: The Nativist Ethnography of Tawfiq Canaan and His Jerusalem Circle,” Jerusalem Quarterly File (2004): 24.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 134.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 140.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 140.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 140.

Nashef, “Tawfik Canaan,” 24.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 140.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 136.

Nashef, “Tawfik Canaan,” 24.

Canaan, “The Taufiq Canaan Memoirs, Part 2,” 140.