Early Life and Memories of Home

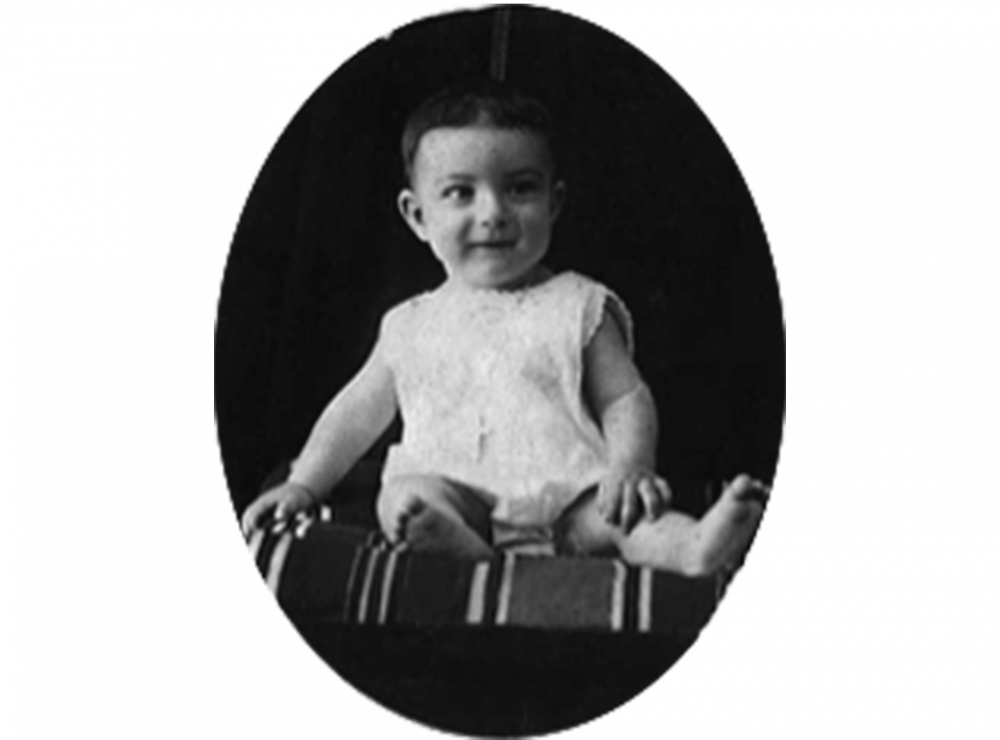

Issa Boullata was born in Jerusalem on February 25, 1929, to Burbara Ibrahim Atalla and Yusuf Isa Boullata, both of whom were also born in Jerusalem. He was the eldest of six children—his siblings were René, Andrea, Jamil, Su‘ad, and Kamal.

Boullata’s first home was a rented ground-floor apartment in Upper Baq‘a; when he was five, his family moved to the Thawri neighborhood. In Hayy al-Thawri, he lived in another rented apartment on the ground floor. His home lay at the heart of Jerusalem’s landmarks. From his bedroom window or front door, Boullata could see the Old City and al-Aqsa Mosque to the south, separated from him only by a hill and valley. Atop the hill lay Prophet David’s neighborhood, one of the oldest Jerusalem neighborhoods outside the Old City. Farther beyond the valley was Jaffa Gate and Bethlehem. To the west, he had a view of Ramleh and Jaffa. His grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins lived nearby and all over Palestine. Others were settled in the United States, Europe, and different parts of the Arab world.

For Boullata, Jerusalem’s historic and natural landscape, which he took in every day by virtue of his home location, was a constant reminder of ancient roots and historic connection to the city. According to his memoir, his paternal grandfather built monuments that still stand in Jerusalem today, including the Mari Mitri School and Dabbaghah shopping center.1

Education

Boullata’s education began in the Thawri Elementary School for Boys and Girls, where he attended kindergarten and primary school. He retained sporadic and fond memories of his early education:

I do not remember now what I learned on that first day of my first academic year, 1934-1935. But I remember it was a happy day which I did not want to end. Yet it ended with the ringing of a bell, from which I understood that my day was divided into times for learning, times for rest and play, and times to eat or go home. On the next day, I came early to school, eager to continue my contact with a new place which had brought me great happiness and in which I had begun to absorb new knowledge in a most pleasant way and to win new friends in play and study.2

It was during his first year at al-Thawri School, in 1934, that five-year-old Boullata became captivated by Arabic in both its written and spoken forms. Every morning, the school’s headmistress recited the opening chapter of the Quran, the Fatiha, and the children echoed her words. To teach reading and writing, the school’s curriculum relied on Khalil al-Sakakini’s four-volume reading books.3 In this way, Boullata’s primary school teachers had a profound influence on his life and instilled in him a love for literature, paving the way for his future scholarly pursuits. Boullata was particularly impacted by a visit from Sakakini himself. The visit was not only exciting, but in some ways symbolic of a greater purpose:

I admired Khalil Sakakini and wanted to be like him when I grew up, a good teacher and educator with an excellent knowledge of Arabic language and literature. I later learned that he was the author of more than a dozen books; that he had been an indomitable man whose participation in Palestinian politics in Ottoman and British times often led to his imprisonment. He always cherished freedom and dignity and truth and justice as essential human values worth struggling for.4

Four years later, however, Boullata switched to the Christian College Des Frères, where he had less access to books. In search of literary material, Boullata turned to his father Yusuf Boullata’s book collection and the library at the Jerusalem YMCA.

Despite the shortage of books, Boullata’s literature teacher, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, was one mentor greatly responsible for encouraging his love of Arabic literature. (Boullata would go on to translate two of Jabra’s books—The First Well: A Bethlehem Boyhood and Princesses’ Street: Baghdad Memories—and write several critical studies of the author’s works.) Both stayed in touch throughout the years, and their written correspondence is preserved in a volume collecting their letters from 1966 to 1994.5

Boullata’s parents raised him and his five siblings according to the rites of the Orthodox Church in Jerusalem. For the rest of his life, Boullata remained devoted to the Eastern Orthodox Church, to the point that he was once, at the age of 14, punished in school for refusing to say that the Orthodox were schismatic.

In 1947, Boullata graduated from his secondary school with distinction.

Growing Up in Occupied Palestine

Despite his young age, Boullata sensed the tensions that charged Jerusalem’s atmosphere in the 1930s and 1940s. While his parents tried to provide a sheltered upbringing, they could not completely stop exposure to the threats and dangers encountered daily in British-occupied Palestine. Like many others in al-Thawri neighborhood, the Boullata family home was routinely searched and ravaged by British soldiers. On one such occasion, Boullata remembers seeing his father dragged out of the house in his pajamas, remnants of shaving cream still on his face.

Another time, British soldiers stopped him and his father as they were taking a walk and forced them to clear the street of nails. At the age of nine, he witnessed an armed altercation between a Palestinian and a British soldier.

Throughout the turmoil that characterized Jerusalem during the British Mandate, Boullata’s mother kept her family afloat by prolonging their food provisions and uplifting everyone’s spirits.

Between 1947 and 1948, at the age of 19, Boullata enrolled in Jerusalem law classes while working as an accountant for the British Government of Palestine, then at Barclays Bank. One of his colleagues, Khalil Janho, carried out two operations in which Boullata refused to take part: the first involved robbing an armored car coming from Barclays; the second, the bombing of the Palestine Post, in which 20 Jewish staff were killed. The law school shut down with the termination of the British Mandate, and Boullata also lost his bank job effective May 15, 1948, the day after the British withdrawal from Palestine and the proclamation of the establishment of the State of Israel. He was left without any source of income.

These were the circumstances that Boullata had to navigate in his youth, with events culminating in the Nakba, which broke up his family and scattered them across the globe, homeless. Nineteen years old when Israel was established, Boullata lamented: “I saw the Nakba eat away at my country, destroy the fabric of my society, and disperse my people in different directions as Israel rose to become a new nation, a Jewish state, immediately recognized by the US and other countries, while the truncated remnants of Palestine languished in disarray.”6 Later he would write: “No year is burnt into the memory of the Palestinians as deeply and as painfully as 1948.”7

Starting a Family

Between 1949 and 1968, Boullata worked in different secondary schools as a teacher of Arabic literature. In 1957, he met Marita Joan Seward while she was visiting the Holy City. They were engaged in 1959 and married a year later in Jerusalem, where they had all their four children. He remarked to one of his students decades later: “My wife, my children and their spouses, and my grandchildren are the most valuable part of my . . . life.”8

University Career

Not long after his marriage, Boullata enrolled in the University of London and graduated four years later with a BA with honors in Arabic and Islamics.

Boullata left Jerusalem in 1968, a year after Israel occupied East Jerusalem and the remainder of Palestine. He moved with his family to Hartford, Connecticut, where he became Assistant Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at Hartford Seminary. In 1969, he received his PhD in Arabic literature from the University of London. By 1970, Boullata was Associate Professor at Hartford Seminary and the coeditor of the journal The Muslim World. He moved to Canada with his wife and four children in 1975 to teach at McGill University and remained there for the next 30 years.

On their way to Montreal, Quebec, the family was stopped at the Canadian border, where an exchange took place between Boullata and the immigration officer. While checking Boullata’s papers, the officer noticed the documents stated that Issa Boullata was born in, “Jerusalem, USA.”

“Where were you born?” asked the officer, to which Boullata responded, “In Jerusalem, Palestine.” An argument ensued in which Boullata tried to convince the officer he was born in Palestine. The officer, for his part, wanted to put down, “Israel.”

“There was no Israel when I was born in 1929,” Boullata insisted. Eventually, the family was let through, but the officer was not convinced.9

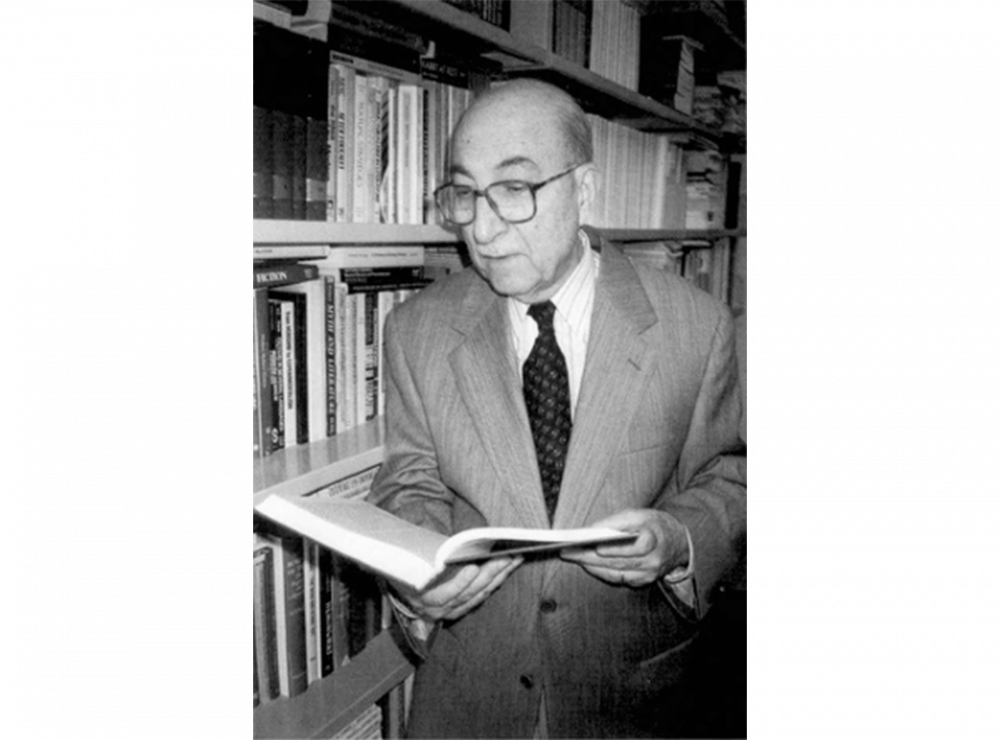

Literary and Academic Life

Even a cursory glance at Boullata’s oeuvre shows the range of his interests and expertise. While his focus was modern Arabic literature, he studied French, English, and Russian literature in depth, as well as medieval, classical, and early Arabic literary traditions. As a translator, he published, edited, and reviewed volumes on translation theory and methodology. His command of Arabic allowed him to branch out to studies on Quranic exegesis, Muslim theology, and classical Arabic works on Islamic mysticism. Apart from literature, Boullata also published on modern Arab history and politics.

His course offerings at McGill were as diverse as his literary publications. He taught cases on Arabic language and literature across different time periods, Quranic studies, and selected medieval and modern authors and literary figures.

Boullata also played a pivotal role in shaping the Institute of Islamic Studies at McGill University. He served as assistant director of the institute and then as acting director. Between 1993 and 1995, he led McGill’s State Institutes of Islamic Studies (IAIN) Development Project in Indonesia and was able to raise funds for the project to support it for an additional five years.10 He retired from McGill in 2004, after which he dedicated some time to publishing a collection of his short stories. Apart from his university career, Boullata was member of several professional organizations, including the Middle East Studies Association of North America, American Association of Teachers of Arabic, Canadian Society for the Study of Rhetoric, and the International Comparative Literature Association.

Awards and Honors

Boullata received several awards for his literary works and translation, including the Arkansas Arabic Translation Award, which he won twice: once for Jabra Ibrahim Jabra’s The First Well: A Bethlehem Boyhood (1993) and another for Ghada Samman’s The Square Moon (1997).11

Death

Boullata passed away on May 1, 2019, in Montreal, Canada. His four children were present at his death.

The Enduring Influence of Jerusalem

Boullata wrote to inspire. For him, words were windows onto different worlds:

My creative Arabic writing has been influenced by modern fiction writers in the Arab world, as well as in Europe and America. I am fascinated by the way in which words written on paper can be made to create in the mind of the reader a whole universe teeming with characters, events, and images of life and society. Through words I can influence the thoughts and feelings of others with regard to issues I like, causes I defend, and ethical behavior I advocate. But all this has to be done in an artistic manner, aesthetically acceptable and illusively possible.12

Throughout his life, Boullata’s roots in and memories of Jerusalem continued to anchor him to the city and define his identity. While in many ways unique, Boullata’s memoirs and literary works surrounding Jerusalem are a form of micro-history, representative of a broader experience of the events that led to the establishment of Israel and the dispossession of the Palestinians. His is not just a heartfelt recollection of home in the distant past, but a real reaction and important witness to the story of Jerusalem.

Selected Works

Authored

“The Concept of Modernity in the Poetry of Jabra and Sayigh.” Edebiyat 3 (1978): 173–89.

Review of This Year in Jerusalem, by Kenneth Cragg. Religious Studies Review 10, no. 2 (1984): 147.

Trends and Issues in Contemporary Arab Thought. New York: SUNY Press, 1990.

Review of The Mufti of Jerusalem: al-Hajj Amin al-Husayni and the Palestinian National Movement, by Philip Matter. Religion Studies Review 16, no. 4 (1990): 365.

Review of Jerusalem in History, edited by K. .J. Asali. Religious Studies Review 17, no. 2 (1991): 134.

“Jabra Ibrahim Jabra.” In Contemporary World Writers, edited by Tracy Chevalier, 269–70. London: St. James Press, 1993.

“Jabra Ibrahim Jabra.” In Encyclopedia of World Literature in the 20th Century, vol. 5, 329–30. New York: Continuum, 1993.

“Jabra 1920–1994.” Jusoor: The Arab American Journal of Cultural Exchange, Present and Future 5–6 (1995): 145–55.

“Jabra wa-l-khuruj min al-madar al-mughlaq.” In al-Qalaq wa-tamjid al-haya: kitab takrim Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, edited by ‘Abd al-Rahman Munif, 49–57. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-‘Arabiyya li-l-Dirasat wa-l-Nashr, 1995.

“Review of Giving Voice to Stones: Place and Identity in Palestinian Literature,” by Barbara McKean Parmenter. Journal of Palestine Studies 25, no. 3 (1996): 106–8.

Return to Jerusalem. [In Arabic.] Beirut: Dar al-Ittihad, 1998.

Rocks and a Wisp of Soil. [In Arabic.] Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-‘Arabiyya li-l-Dirasat wa-l-Nashr, 2005.

A Retired Gentleman and Other Stories. London: Banipal, 2007.

Outlines of Romanticism in Modern Arabic Poetry. [In Arabic.] Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-‘Arabiyya li-l-Dirasat wa-l-Nashr, 2014 [1960].

The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem. Quebec: Linda Leith Publishing, 2015.

Edited

Critical Perspectives on Modern Arabic Literature. Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980.

(with Terri DeYoung) Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Literature. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Literary Structures of Religious Meaning in the Qur’an. London: Routledge, 2013.

Translated

Embers and Ashes: Memoirs of an Arab Intellectual, by Hisham Sharabi.

Flight against Time, by Emily Nasrallah.

Fugitive Light, by Mohammed Berrada.

Three Treatises on the I‘jaz of the Qur’an.

Sources

Abdel-Malek, Kamal. “Professor Issa J. Boullata: A Profile of an Intellectual Exile.” In Tradition, Modernity, and Postmodernity in Arabic Literature: Essays in Honor of Professor Issa J. Boullata, edited by Kamal Abdel-Malek and Wael Hallaq, 1–27. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

Boullata. Issa. “My First School and Childhood Home.” Jerusalem Quarterly 37 (2009): 27–44.

“Boullata, Issa J. 1929– .” Encyclopedia.com. Accessed August 22, 2023.

Johnson, Penny. “Idylls of Jerusalem.” Review of The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem, by Issa Boullata. Jerusalem Quarterly 60 (2014): 131–35.

McKhail, Ayah Victoria. “What Remains.” Review of The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem, by Issa Boullata. Literary Review of Canada, September 2014.

Salah, Maha. Review of The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem by Issa J Boullata. Jerusalemites, October 5, 2015.

al-Tajriba al-jamila: rasa’il Jabra Ibrahim Jabra ila Issa Boullata min 1966 ila 1994 [A beautiful experience: Letters from Jabra Ibrahim Jabra to Issa Boullata, 1966 to 1994]. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-‘Arabiyya li-l-Dirasat wa-l-Nashr, 2001.

[Profile photo: Wikipedia]

Notes

Maha Salah, Review of The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem by Issa J Boullata, Jerusalemites, October 5, 2015.

Issa Boullata, “My First School and Childhood Home,” Jerusalem Quarterly 37 (2009): 28.

Penny Johnson, “Idylls of Jerusalem,” review of The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem, by Issa Boullata (Quebec: Linda Leith Publishing, 2014), 132.

Boullata, “First School,” 34.

al-Tajriba al-jamila: rasa’il Jabra Ibrahim Jabra ila Issa Boullata min 1966 ila 1994 [A beautiful experience: Letters from Jabra Ibrahim Jabra to Issa Boullata, 1966 to 1994] (Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-‘Arabiyya li-l-Dirasat wa-l-Nashr, 2001).

Ayah Victoria McKhail, “What Remains,” review of The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem, by Issa Boullata (Quebec: Linda Leith Publishing, 2015).

Salah, Review.

Kamal Abdel-Malek, “Professor Issa J. Boullata: A Profile of an Intellectual Exile,” in Tradition, Modernity, and Postmodernity in Arabic Literature: Essays in Honor of Professor Issa J. Boullata, ed. Kamal Abdel-Malek and Wael Hallaq (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 6.

Abdel-Malek, “Professor Issa J. Boullata,” 1.

Abdel-Malek, “Professor Issa J. Boullata,” 7.

“Boullata, Issa J. 1929–,” Encyclopedia.com, accessed August 22, 2023.

“Boullata, Issa J. 1929–.”