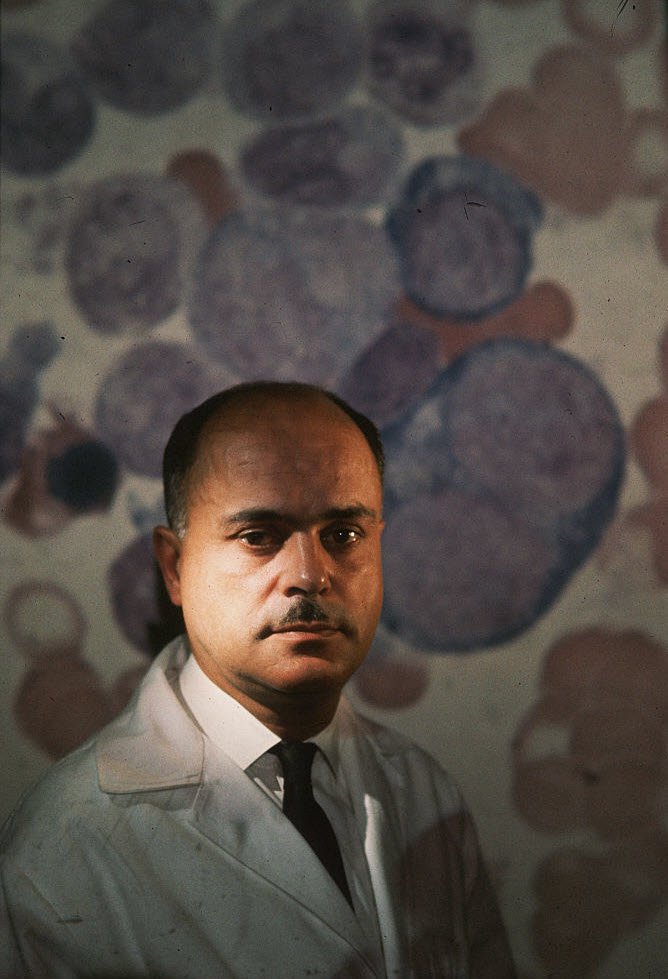

Amin Saleh Majaj (b. 1921 in Ramallah) was a distinguished pediatrician whose contributions to nutrition and child heath saved thousands of Palestinian children in refugee camps and elsewhere. He established and headed the pediatrics department at the Augusta Victoria Hospital in Jerusalem. At various times he was appointed Minister of Health, Social Affairs, and Construction and Development, and he served as mayor of East Jerusalem and representative of Jerusalem in the Jordanian parliament.

Childhood and Education

Majaj was born in Ramallah on March 21, 1921. His family, originally from Yemen, worshipped at the Anglican Episcopal Church. He had three siblings: Hanna, Hanneh, and As‘ad (who died in a drowning accident when he was seven years old).

Bahia, Majaj’s mother, was the daughter of Dr. Philip Maalouf, a Lebanese doctor sent to Ramallah by the Friends’ Society in 1890. Saleh Ibrahim Majaj, Amin’s father, taught at the Greek Orthodox School in Jaffa. Saleh had lived in Birzeit, but in the early 1920s, he and his wife moved with their four children from Birzeit to Jerusalem.

In 1936, Majaj learned to play the violin at the Palestinian Conservatory of Music in Jerusalem. He later formed a band that comprised several instruments. Majaj became so good at music that he was awarded (in the 1930s) the prize for second-best violinist in all of Palestine.

As for his education, Majaj studied at St. George’s High School in Jerusalem. In 1945, he received a diploma in medicine and surgery from the American University of Beirut (AUB). He then specialized in child health and obtained a degree in pediatrics (on a scholarship from the British Council) from the University of London, with an extension in Edinburgh, in 1954.

The Repercussions of the 1948 War on Infant Health

When Majaj was studying medicine at the AUB in Lebanon, he met Betty Dagher, a Lebanese student at the Nursing school. They got married in 1947, and Dagher Majaj moved with her husband to Jerusalem. The couple had three daughters (Lina, Randa, and Hala) and one son (Saleh).

At the very start of his career, and just shortly after he graduated from the AUB, Majaj was confronted with the horrific reality of the Palestinian displacement of 1948 (Nakba). Working with his wife and sister (both of whom were nurses), Majaj attended to the sick and injured under the threat of attacks and immediate bombs during the war. He treated the dozens of orphans who were found and rescued by Hind al-Husseini at Dar al-Tifl al-Arabi free of charge.

The compassion that Majaj had is worth elaborating on, as it extended beyond denomination or nationality. His daughter Lina recounts one of the stories her father had shared:

During the war of 1948, he came across a religious Jew who was injured and bleeding. My father carried him to safety to a nearby hospital while shots rang in the air. He saved the man’s life while putting his own life at risk, and told the story like it was what anyone would have done.1

Majaj was appalled by the tragic consequences of the 1948 War on Palestinian children, many of whom were dying from gastroenteritis (an illness triggered by the infection and inflammation of the digestive system) and other deficiency diseases.

Looking into the poor condition of infants, Majaj realized that it was the mothers’ lack of nutrition that largely influenced the infants’ health. The mothers had insufficient intake of calories and were especially low on protein (as well as iron and vitamin B12), all of which made breastfeeding ineffective. The iron-deficiency anemia of the mothers led to diseases such as kwashiorkor2 (a form of severe protein malnutrition) in the infants.

Majaj immersed himself in research, looking for alternatives and treatments for malnutrition by which to save children and help the families. His research in the field of malnutrition and associated diseases (with a focus on Palestinian children in refugee camps) would become internationally acclaimed. His findings have been taught worldwide, and many of his articles were published in medical journals, including the Egyptian Medical Journal (1956), the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1966), the Gazette of the Egyptian Pediatric Association (1960), the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1963), and various British as well as German medical journals.

Majaj was also invited to several conferences, including the UNICEF conference in Istanbul (1957) where he contributed about abnormal hemoglobin, and in Tunis (1965) where he headed the Jordanian delegation to the fourth congress of the Union of Arab Physicians. He was also invited by the US Department of State (in 1959) on a two-month visit where he met with specialists in the United States. Following these visits, he applied for a research grant and was awarded (in 1963) a grant for three consecutive years whereby he demonstrated the effects of vitamin E in humans. The research was considered significant among scientists, and resulted in treating patients with vitamin E. His impressive work on the subject also led to the inauguration of a research lab, for which Majaj (in 1963) received the highest medal (Kawkab—First Grade) by King Hussein bin Talal of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

For all this research work, he has been called “the initiator of medical research and training in Palestine.”3

Impressive Contributions to Jerusalem Hospitals, Health Care Capacity, and Ministries

Majaj founded and headed the first Palestinian Pediatric Unit at the Augusta Victoria Hospital in Jerusalem. Augusta Victoria had been built in 1910 (following the 1898 visit of Kaiser Wilhelm to Jerusalem) as a Lutheran hospice for pilgrims. In 1949, Zulaykha Shihabi, a prominent Palestinian Jerusalemite, persuaded the Red Cross to give her part of the building to use as an emergency ward for Palestinian refugee children from the war. She asked Majaj to run the children’s ward, and he accepted. In 1950, Majaj was made Head of Pediatrics there, a position he held until 1991.

In addition to his clinical work, Majaj was dedicated to training pediatricians. Dr. Adrineh Karakashian, a distinguished pediatrician in Jerusalem who treated thousands of Palestinian children over more than 60 years, wrote that Majaj was her “spiritual leader in medicine. He taught me never to neglect my duties, to prioritize tasks and consider the child as always the first priority.”4

Not only did Majaj stand out as a highly skilled doctor and researcher, but he was also a great administrator. He was on the board of al-Ahli Hospital (in Gaza) and St. Luke’s Anglican Hospital (in Nablus). Among his several contributions was his integral role as board member at the Arab Development Society in Jericho (founded by Musa Alami in 1952 to help Jericho’s refugees by teaching them agricultural and other skills).

From 1950 until 1964, Majaj was Director of the Child and Maternity Care Center, which was affiliated with the Arab Women’s Union in Jerusalem. He was also among the key figures who helped the late Labib Nasir establish the YMCA in East Jerusalem (the institution was founded in 1948 in a tent in the Aqabat Jabr refugee camp; the building was completed in 1960; the East Jerusalem YMCA remains active today). Majaj eventually served as Chairman of the YMCA Board of Directors. He was also a member of the Arab Orphan’s Committee (Lajnat al-Yatim al-‘Arabi), which was established in Haifa in 1940 and then expanded to Amman and Jerusalem in 1949, after the war.

Jerusalem municipal administration roles

In 1950, following the postwar division of the city, Majaj became a member of the East Jerusalem municipal council. In 1957, as well as in 1964, the Jordanian government appointed him as Minister of Health, Reconstruction, and Social Welfare. Between 1957 and 1964, he was elected as a member of the Jordanian parliament (in the Jordanian government) as a representative of Jerusalem; he took on that role again from 1967 until 1988.

In 1956, then mayor of East Jerusalem Ruhi al-Khatib had to go abroad for a year, and Majaj became acting mayor for that year. Majaj also held the position of titular mayor of East Jerusalem in 1994, when al-Khatib passed away.

In her memoir, Majaj’s wife, Dagher Majaj, shared the following anecdote about Majaj’s municipal leadership:

In 1957, during his term as acting mayor, Amin wanted to impress upon the people of Jerusalem the importance of cleanliness and give people the responsibility of keeping their city streets clean. He wanted to lead by example, so he summoned the municipal councilors and asked them to all wear street sweepers’ uniforms and instructed them to sweep the garbage at the entrance of Damascus Gate with him in the lead. Foreign consuls and the press gathered to witness the occasion, and Amin presented them with a speech on cleanliness. Many cities followed suit.5

Continued Efforts following the 1967 War

The 1967 War not only led to the displacement of Palestinians and the destruction of their homes; hospitals were bombed as well. The Augusta Victoria was among the hospitals hit during the war. In fact, it sustained a direct hit. Again, as in 1948, Majaj bore witness:

When the war [of 1967] began on June 5, Dr. Majaj drove quickly to the hospital. He remained there until the ceasefire. He watched as the new pediatrics department, which had taken him years to build, was completely destroyed. Dr. Majaj’s lab, in an adjacent building, was damaged but not ruined.6

Dagher Majaj describes how the 1967 War was a “bitter blow for everyone,” and that it was “catastrophic for Amin” to see his beloved Jerusalem under occupation:

The destruction of the new children’s ward and the occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, by the Israelis all weighed heavily on him. He had worked tirelessly for almost twenty years. He was the father of pediatrics in Jerusalem, serving anyone with a need regardless of their means, and had put Jordan on the scientific map. He had helped create a positive path for the Palestinian and Jordanian people.7

The medical expertise of Majaj was urgently needed during and after the 1967 War, and he did not hold back. He made sure that the casualties were transported to the Augusta Victoria Hospital in due time. He became medical director of the hospital in 1977. In addition, he dedicated his pediatric assistance (as of 1967) to the Makassed Hospital in Jerusalem, which he then also headed from 1977 until 1982.

Majaj was an esteemed Jerusalem figure who courageously stood up to the challenges thrown at him and his people by war, conflict, and political violence.

In 1997, he was ordained as a lay canon in the Anglican Church of Jerusalem.

Death and Burial

Majaj died in East Jerusalem on January 4, 1999. He was acting mayor of East Jerusalem at the time of his death.

In her memoir, his wife, Dagher Majaj, described his funeral thus:

President Arafat decreed a formal funeral for Dr Amin Majaj. His coffin was draped with the Honor of the Flag of Palestine. The President’s wreath was held high—as the Boy Scouts, dressed smartly in their uniforms and playing trumpet and drum, marched at the head of the procession of mourners up Nablus Road from the East Jerusalem YMCA to St George’s Cathedral. The officials at the service were Right Rev. Riah Abu El-Assal, who was Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem at that time; his predecessor Right Rev. Samir Kafity; Right Rev. Suheil Dawani, Diocesan Secretary and the Pastor of the Arab Episcopal (Anglican) Congregation at St George’s Cathedral; the English Dean of the Cathedral, Dean Emeritus, the Very Rev. Michael Sellors; and Rev. Samir Habiby, who was a close friend of the family and a Canon of St George’s Cathedral.

The Honorable Faisal Husseini, PLO representative in Jerusalem and a Palestinian Authority minister, gave an eloquent eulogy on behalf of President Arafat and praised Amin for his patriotism, his leadership in times of crisis, the high caliber of his services to humanity, his amazing love for his people and in general his services to the national community. Following the service, our motorcade drove across “The Green Line” into West Jerusalem, past Jaffa Gate to the Anglican cemetery on Mount Zion, where Amin was finally laid to rest. The funeral procession included bishops, religious leaders, senior members of the cabinet in the Palestinian Authority, members of Legislature and other dignitaries of East Jerusalem. The Palestinian flag that draped the coffin was handed to me to keep by Faisal Husseini.8

Following the service, Majaj was buried at the Anglican cemetery on Mount Zion (past Jaffa Gate).

Publications

A collection of Majaj’s professional medical publications can be found here.

Sources

Alghad Extra. “Get Acquainted with the Life Journey of the Jerusalem Amin Majaj Doctor and Distinguished Politician.” [In Arabic.] March 28, 2019.

Dagher Majaj, Betty. A War without Chocolate: One Woman’s Journey through Two Nations, Three Wars and Four Children. N.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

Dudin, Anwar. “Medical Education in Palestine, Past, Present and Future.” First International Faculty of Medicine Conference 2008.

Madsen, Ann Nicholls. Making Their Own Peace: Twelve Women of Jerusalem. New York: Lantern Books, 2003.

Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs. “Al-Majaj, Amin (1921–1999).” Accessed September 16, 2021.

Schor, Laura S. Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem: An Artist’s Life. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2019.

Tamari, Salim. “Jerusalem: Subordination and Governance in a Sacred Geography.” In Capital Cities: Ethnographies of Urban Governance in the Middle East, edited by Seteney Shami (Toronto: University of Toronto, 2001), 175–198.

Wikipedia. s.v. “Amin al-Majaj.” Last modified December 23, 2020, 21:29.

[Profile photo: Aziz al-Assa blog.]

Notes

The words of Lina Majaj in Betty Dagher Majaj, A War without Chocolate: One Woman’s Journey through Two Nations, Three Wars and Four Children (n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015), 228.

Kwashiorkor is “an African name meaning ‘deposed child,’ referring to the sickness a baby gets when a new child comes.” Dagher Majaj, A War without Chocolate, 112.

Anwar Dudin, “Medical Education in Palestine, Past, Present and Future,” First International Faculty of Medicine Conference 2008.

Dagher Majaj, A War without Chocolate, 120.

Dagher Majaj, A War without Chocolate, 117.

Laura S. Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem: An Artist’s Life (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2019), 157.

Dagher Majaj, A War without Chocolate, 169.

Dagher Majaj, A War without Chocolate, 209–10.