April 1948: Zionist forces invade Qatamon. After three days and 150 Arabs dead, the neighborhood falls. All surviving residents flee. The Sakakinis leave their home on April 30 and head for Cairo by car. They are one of the last families to leave the Jerusalem neighborhood.

May 1948: The new State of Israel is declared, leading to the exile of over 750,000 Palestinians. This number includes over 73,000 Palestinian Arabs from Jerusalem and nearby villages (see The West Side Story).2

June 1948: Israel passes Abandoned Property and then Abandoned Areas Ordinances which defined as “abandoned” “any area or place conquered by or surrendered to [Israeli] armed forces or deserted by all or part of its inhabitants, and which has been declared by order to be an ‘abandoned area.’ All properties in these areas are also declared ‘abandoned’ and the Government is authorised to issue instructions as to the disposition of such properties.”3

October 1948: Israel passes the Emergency Regulations Regarding the Cultivation of Fallow Lands and Unexploited Water Sources, which give the Minister of Agriculture the power to retroactively authorize the seizure and reallocation of lands that had already been seized and reallocated.4

December 1948: Israel passes a law granting the office of the Custodian of Absentee Property legal status and authority to define all Arabs displaced during the war as “absentees,” regardless of whether or not they returned. This term applied to hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs, including the Sakakinis, thereby allowing the Israeli government to expropriate their properties, rendering them state property.5

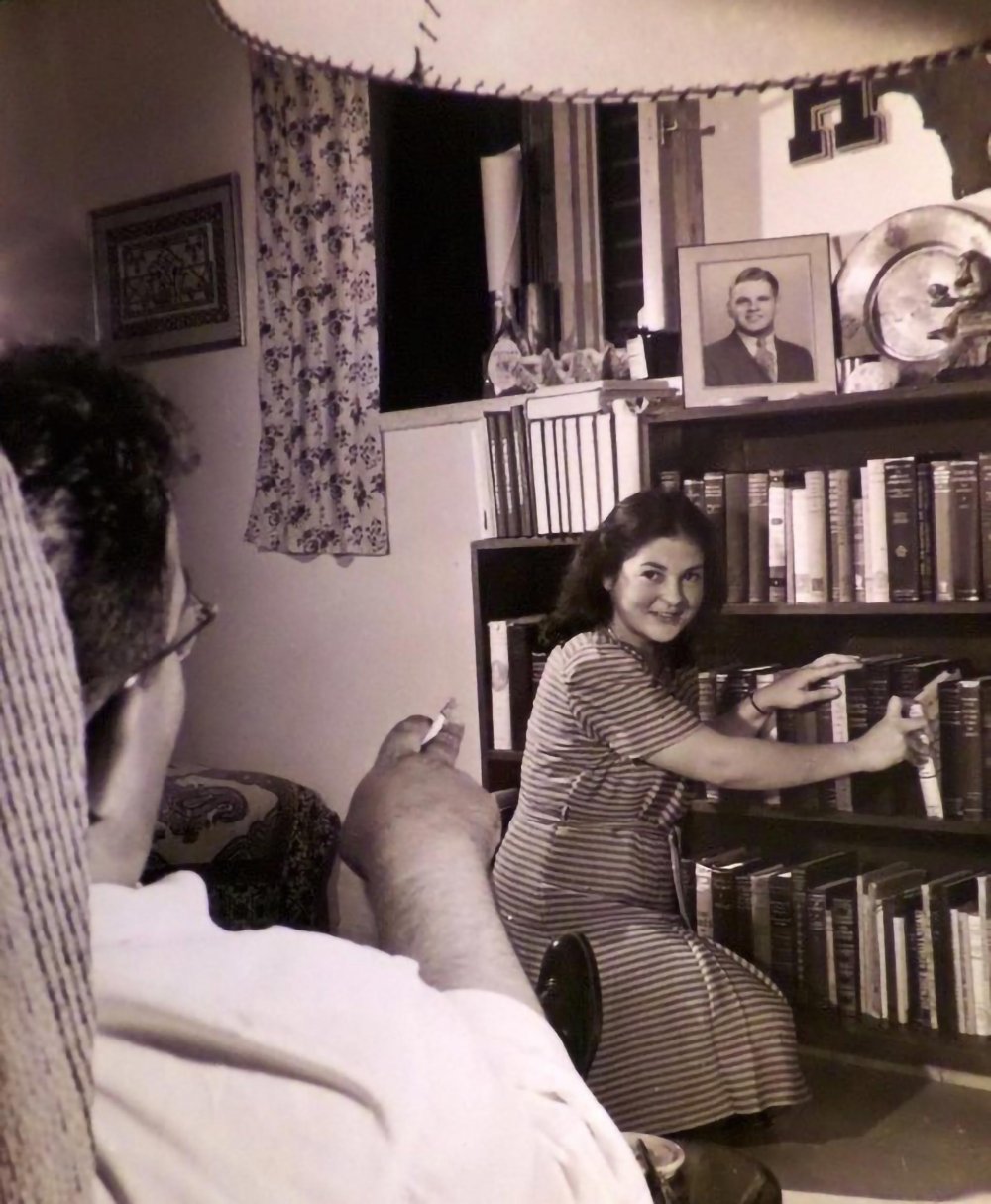

1949: Israel establishes Amidar, a state-owned public housing company, funded largely by the Jewish Agency for Israel, the Jewish National Fund, and the Israeli government. Amidar is tasked with providing subsidized and rent-controlled housing, primarily for lower-income Jewish families. To offer housing for the large number of Jews moving in, many homes in Qatamon are divided, including the Sakakinis’. Amidar managed the division of the Sakakini home and thereafter.

March 1949: The Custodian of Absentee Property rents the first floor of the Sakakini house to the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO), which runs a nursery school on the first floor of the house.

April 1949: The Langer family, likely Jewish evacuees from the emptied Jewish Quarter in the Old City, rents the second floor of the Sakakini home.