Overview

Credit:

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [matpc 22815]

Rereading Jerusalem’s History

Snapshot

Any snapshot of Jerusalem today must take into account the historical roots of its neighborhoods and communities—Palestinian and Israeli. Waves of immigration were shaped by changes in the city’s control. And the Nakba (Catastrophe), when Palestinians were made refugees in 1948, halted the development of a vibrant multiethnic, multireligious city, turning it into the shrunken redoubt of the impoverished and dispossessed. Here, we touch upon this history with one of Palestine’s preeminent scholars of the city, Dr. Nazmi Jubeh.

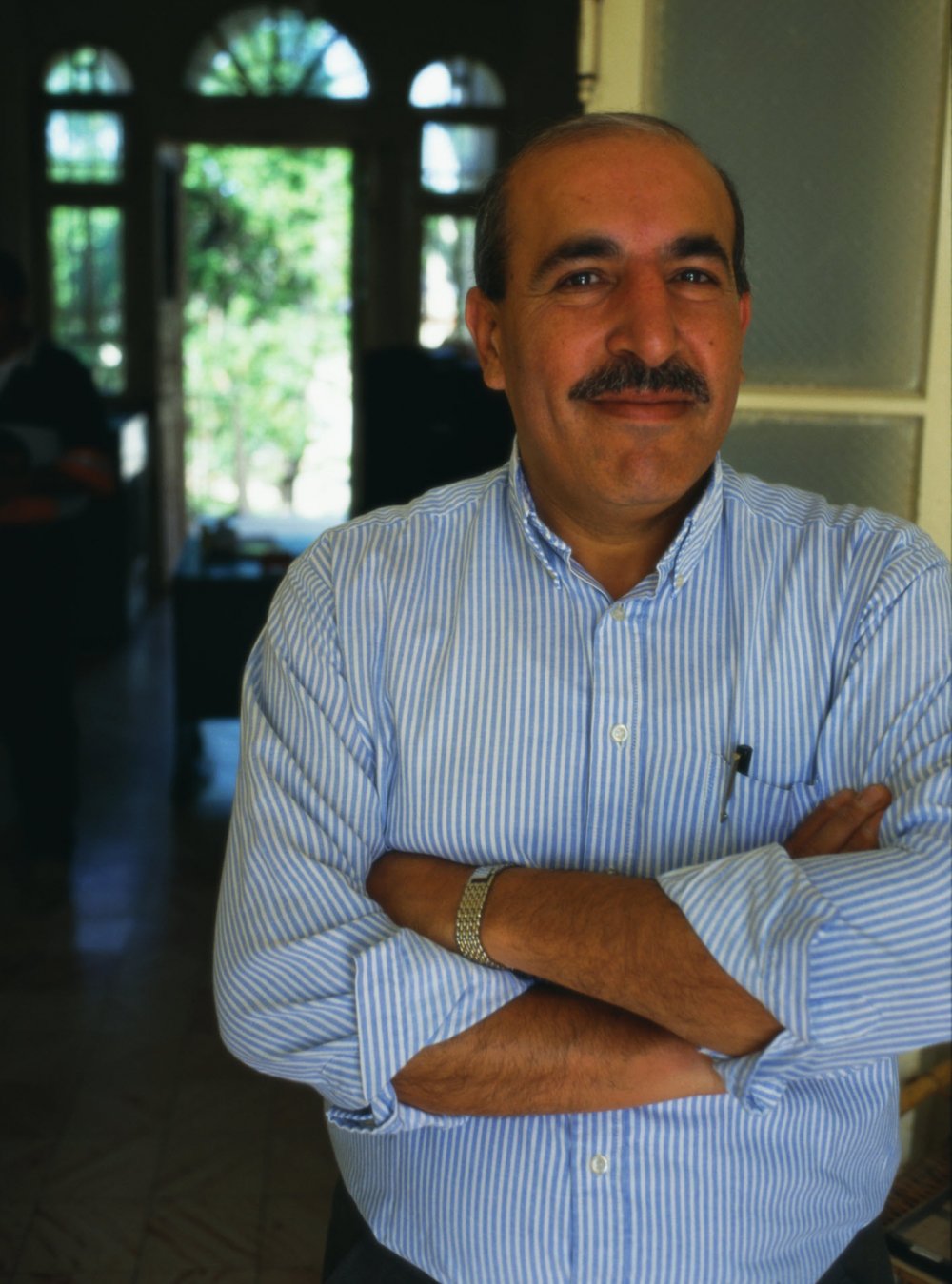

The history of Jerusalem is often told through the lens of modern politics—which is too often history written by the victors. For Palestinian scholars, challenging this narrative has meant “rereading” history and archeology—initially also produced from a European colonial perspective—to ensure the inclusion of more varied voices and narratives, including their own. Dr. Nazmi Jubeh, associate professor of history and archaeology at Birzeit University (Palestine), has contributed numerous books and articles to this effort. Jerusalem Story interviews him here on the city’s ancient and more recent history.

Jubeh served as codirector of Riwaq Centre for Architectural Conservation in Ramallah (1992–2010) and the Islamic Museum at the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem’s Old City (1980–84). He studied at the University of Tübingen and holds a PhD in history and archaeology of the Middle East.

Jubeh was born in the Old City of Jerusalem in 1955, and his family traces its history there back for centuries.

Jerusalem Story: Can you describe for us how the Palestinian community that exists in Jerusalem today is linked to the history of the city? When visitors to Jerusalem see the Old City, for example, and its distinctive architecture, how are today’s communities connected to that ancient history?

The people who made this history are the owners of these historical buildings, buildings that were constructed by their ancestors, in a continuity of family life at least since the post-Crusader period when Jerusalem was recaptured by Salah al-Din in 1187. [Residents] who had been living there before the Crusader period in Jerusalem returned to the city and others joined them from other parts of Palestine and surrounding countries. People even came from Andalusia, Spain, North Africa, Iraq, Egypt. This integration of communities reached its peak in the so-called Mamluk period (approx. 1260–1516). In this period, major parts of the Old City were rebuilt, especially markets and public buildings around the al-Aqsa Mosque. Families that were living in the city in this period are still living in the city 700 to 800 years later.

Of course, as [Jerusalem is] an important religious city, Jewish communities began to establish themselves in the city as well. Immigrants came from North Africa and Spain and Eastern Europe to Jerusalem. The Jews lived in a small community in the Jewish Quarter.

The Christian community can be divided into several parts—some Christian communities existed in the city from the Byzantine period and have lived there continuously since then. The Crusader period was a break in the city’s history, where the Europeans settled here for 88 years and then left after Salah al-Din captured it. But Oriental Christian communities continued to live here—Armenians, Georgians, Coptic Egyptians, Ethiopians. On the family level, we can trace some families from the pre-Islamic period until today, living in the city as Christians. So you cannot really separate the communities living in the city from its architecture.

It is different when speaking about the communities living outside the Old City; they are two different demographic groups. One group settled in the second half of the 19th century—mainly Jewish communities and settlers, but we can also speak of different European communities, like Germans, Greeks, Italians, and Americans. In this period, Jerusalem was attractive to so many different communities, but also Palestinians and Arabs came from different parts of the country and from outside Palestine in the second half of the 19th century, when new neighborhoods were growing rapidly outside the walls.

Other types of communities lived outside the city walls, such as the villages of Silwan or Shu‘fat or ‘Anata or Beit Hanina. These old villages, which are very ancient, continued in their existence for many centuries; [they include] Deir Yasin, Lifta, and other villages that Israel incorporated into the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem [after it occupied the city in 1967]. These villages maintained their social structures, although only a very small portion of them still lived off agriculture.

After 1967, because of the efforts by Israelis to construct settlements, these villages became neighborhoods for Jerusalemites who could not build their houses in the [majority] of the city. Eighty-eight percent of the [lands within] the municipal borders of East Jerusalem was confiscated for the sake of settlements or public buildings or constructing new roads or so-called green areas. [As a result], Palestinian communities were squeezed into only 12 percent of the city. That converted most of the neighborhoods, including the old villages, into slums. Traditional life has been lost. Poverty and all of its problems and “diseases” are very well anchored in these communities.

JS: Reading some accounts of life in Jerusalem in the late Ottoman and early British Mandate periods, it is so striking how different religious communities seemed to interact in a much more integrated way than they do today. Can you talk some about that period? And do you think we romanticize this somewhat because the situation is so dire now?

Jerusalem did not learn coexistence and tolerance from modern literature. This was part of the daily experience of its people, who lived with the “other.” Jerusalem was never painted with one color—it was always a multicolored city [with] so many religious communities, so many classes, and [so many] ethnic groups who learned to live together.

It was not always easy. Conflicts were part of daily life in Jerusalem between the different communities, but in general, if you compare it with other parts of the world . . . the Jerusalem experience is really something different. Jerusalem never, until recently, experienced the life of ghettoes. Ghettoes were not part of the experience in the Orient in general; this was more of a European invention: the ghettoes for Jews. Just compare the current period with the late Ottoman period. Today we are living with the Israelis, but separated. I think that the national conflict is deeper than the idea of coexistence; the current situation cannot be described as coexistence, because that means that you choose to coexist. We are obliged sometimes to work together or sometimes to go to the hospital together, but this is not coexistence.

Some of the European schools in the late Ottoman period in Jerusalem were Christian schools, but full of Muslim students. That means they chose that; they opened themselves to “the other” without any kind of obligation. Even neighborhoods were mixed. In the Old City, this traditional vision of four quarters, in reality, never existed. There was a concentration of Christians around their holy sites, and the same for Muslims and Jews. The “Christian Quarter” was mixed with Muslims. The “Muslim Quarter” was mixed with Jews and Christians. So it was not really separated, and this naming of these quarters was mostly not by local communities. This was mostly European terminology. This is pre-Zionism. After Zionism, [we saw] a form of national conflict instead of community conflict.

JS: Are there examples that you can give from the Ottoman court records?

There are hundreds of records, thousands of documents. Jerusalem is lucky because we have the records of the Islamic sharia courts from the early Ottoman period—400 years of records of every matter that happened in the city. According to Islamic family law, non-Muslims [may not only consult their own courts] but can also use the Islamic courts. So many Christians had conflicts [with other Christians] and came to the Islamic courts to solve them. The same with the Jewish community—I can tell you of hundreds of documents even from the Mamluk period. (We are also lucky to have 1,400 documents from the late 14th century, an archive of an Islamic judge in Jerusalem.) In these documents, there are many cases dealing with Jewish rights, Christian rights, construction rights, rehabilitation rights, and so on. These Mamluk and Ottoman documents reveal a form of coexistence and tolerance—to a certain degree, of course. But compared with Europe at that time, Jerusalem was a form of paradise for communities that survived together in spite of differences.

There is an interesting case of conflict, [for example,] between Muslims and Jews that took place in the late 15th century over the ownership of a synagogue—the only synagogue in the city at that time. One of the court judges of Jerusalem was an advocate for Jewish rights and even went to Cairo to apply to the sultan, until he managed to dismiss other opinions and to protect Jewish rights in the synagogue. This, despite that there is some gray area [in the law] where one could decide that this was Jewish property or not. I can tell you hundreds of similar stories in Jerusalem.

JS: For Palestinians, the Nakba, their 1948 dispersal, was a rupture, especially in Jerusalem. Can you put that in historical context and what that has meant since for Jerusalem’s communities?

About 90 percent of Jerusalem was lost in the Nakba, becoming West Jerusalem. All of the modern [neighborhoods], institutions, infrastructure were all concentrated in West Jerusalem. It was lost. It was not only lost—people were evicted from their houses. Those living in the neighborhoods of West Jerusalem were mostly the middle and upper class, the class that has the capital, the class that could make economic and cultural initiatives. All of that was lost. Those rich Palestinians became refugees in just a few days. The Israelis gained beautiful houses with their furniture and libraries, their pianos. Suddenly, the Israelis became very rich people and the Palestinians of Jerusalem—at least in this case—became refugees with nothing.

The Nakba stopped the development of the city. Jerusalem was, since the second half of the 19th century, rising in a very quick way, developing in all aspects of life—services, goods from all over the world, visitors from every corner of the world, even from a cultural point of view, there were cinemas, theaters—it was a very open and liberal city. So the Nakba stopped all of this development. Palestinians were squeezed into East Jerusalem, both the original residents and the refugees who came over from West Jerusalem. Unfortunately, most of the Palestinian refugees from West Jerusalem from the middle and upper classes continued walking until they reached Jordan or elsewhere; they left the city. Jerusalem was divided into two unequal parts. There was a hostile border, and it was not an attractive city for anybody, but especially for those who were looking for an open life, a modern life, [opportunities] to invest, to develop, [and] educated people. So they went to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, to Europe, the United States, and to Amman, the capital of Jordan. At that time, Jordan was rising as a state and in need of educated people, and we supplied them. What was left after the Nakba in East Jerusalem were mostly poor refugees and the lower class of Palestinian society. The Nakba influenced the city deeply [into] the Jordanian period, which was very short (1948–67). Jerusalem became a neglected city and that made it easy for Israel to control [it] and impose Israeli laws on it—it was really a city empty of leadership and education.

JS: Tell us what it is like to be a Palestinian archeologist working and researching in this time. What are the ways that you see Palestinian history being erased?

We are trying to develop our narrative of history. The [dominant] narrative of history is not only related to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict; we have been challenged in our history from the beginning. We have a disadvantage, because Israeli archeologists continued the work of European/American archeology in the city. They were mostly trained in Europe, and when they began to work in Palestine, in Jerusalem in particular, they were standing [at a different vantage] point than Palestinians were standing. Archeology is not a subject [studied] at all in our community. History was also a very marginal issue. The Israelis challenged our existence—you remember that we were not accepted or recognized as a people. We were recognized as scattered Bedouins who have no history, not even a relationship to the land.

Of course today, the situation is totally different, but still we are working very hard to “reread” history and to write it in a different way. Unfortunately, history and archeology have become a political tool in this conflict—and I admit that I am part of that, too. Because if your existence is challenged and you are being told, “Who are you?” [by someone] arriving yesterday from Poland or elsewhere . . . I can tell you we don’t have a lot of documents, but my family is mentioned in the records of Jerusalem in the 16th century. I don’t know how long I lived in the city before that, but still you are coming and telling me, “Who are you? Do you have any rights in the city?” History is also an instrument for us to prove our existence and to prove that our roots are very deep in the city. It is amazing that these questions are still questions in the 21st century.

We are developing an approach saying that the Palestinian people are [part of] the history of the country, regardless of whether it was Canaanite or Byzantine or Roman. We continued to live in this city; we are the result of all of these nations. People were not deported en masse so that the country became empty and newcomers arrived; this is not the history of Palestine. There is a continuity; the major core of the population continued to live here. Maybe my ancestors were Jewish or Christian—I don’t know. I know that I was born here, my father was born here, my great-great-grandfather was born here. We are from here.

We are trying, without using unscientific propaganda, to say that the Jews who used to live here were perhaps at one time a major demographic group, but they did not then leave the country. They continued to live here. They converted to Christianity. They converted to Islam. We are the outcome of all of these nationhoods.

JS: It is not uncommon in certain circles to hear almost the mirror opposite of Israeli rhetoric that Palestinian history in Jerusalem does not exist—for example, that “there is no Jewish history in the city.” How do you engage with this in an atmosphere where there really is a lot of mythmaking along with the facts?

We have to differentiate between serious academic research and propaganda and political slogans. I do not deny the Jewish relationship to Jerusalem. I do not deny Jewish history in Jerusalem. But I deny the exclusivity of history of Jerusalem as a Jewish city. No one period in the history of Jerusalem was just Jewish; there were always other ethnic groups and religious groups living together in the city.

There are two approaches, one inclusive and the other exclusive. I think that my approach is inclusive. I spoke already of Jewish history in the Mamluk period, and also in this conflict unfortunately, Christian history is a victim, as if the conflict is between Jewish and Muslims in the city and there is no Christian community in the city. This history of the Christian community has been silent in the last five or six decades and needs to be republished. The conflict in Jerusalem is not between Muslims and Jews; it is between Palestinians and Israelis. Unfortunately, the religious dimension . . . has slowly become a central element. I think that this is a huge mistake. Political national conflicts can be solved; religious conflicts are very difficult to solve.

JS: When you look around you today, do you see Israel’s control of Jerusalem as a fait accompli?

Absolutely not, and I do not think that Israel believes this either. More than 40 percent of so-called united Jerusalem is made up of Palestinians—maybe this year [it is] 41 or 42 percent. What kind of future will we have if Israel considers 40 percent of the population of its capital as enemies, all the time trying to control [them], squeeze them, dismantle them? Jerusalem is slowly becoming an apartheid city. You can see al-‘Isawiyya neighborhood with the Israeli settlement around it, built on its land. The infrastructure is so bad; everything is overcrowded, while their neighbors just across the street have open spaces, parks, and all the facilities they need.

The situation cannot continue like this. They are using all measures to try to control the Palestinian community; cameras and Israeli police are everywhere in the city. They believe that what has not been achieved with force will be achieved by using more force. This will explode, and we can see that, we can smell that, every day.