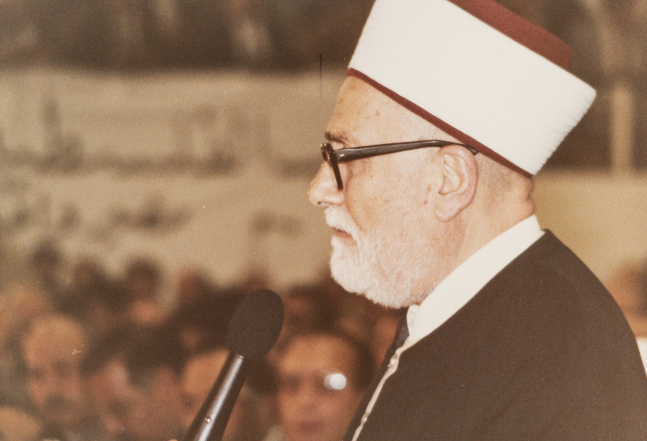

Sheikh Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih was a leading figure in the Palestinian nationalist movement throughout most of his life, which spanned 94 years and virtually all of the 20th century. Today, al-Sayih is remembered for his expertise as a religious and legal scholar and for his refusal to stay silent following Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank in June 1967. In fact, it was his activism directly after the city fell in June that led to Israel exiling him to Jordan in September 1967. He was the first Palestinian whom Israel exiled from the newly occupied Palestinian lands,1 but by no means the last.

The Rise of a Religious Activist

Al-Sayih was born in 1907 in the Qaysariyya neighborhood of Nablus’s Old City to Abd al-Halim al-Sayih and Sabha Bakri. He was educated at schools in Nablus, first at al-Khan and then at al-Rashadiyya al-Sharqiyya, which later became known as the al-Salahiyya school.

Throughout his childhood, al-Sayih attended religious classes in mosques, and in 1920, at age 13, he was selected as part of a group of young scholars to study in Cairo’s famous al-Azhar Mosque. He studied jurisprudence and Islamic sciences at al-Azhar University, earning his higher degree, ahliyya, in 1923, followed by his ‘alimiyya degree in 1925, a specialization for students who wish to study Islamic sciences in depth.2 The former signified successful completion of 8 years of study; the latter, 12—a system of formal degree conferral that began in 1896.

During his time at al-Azhar, al-Sayih also enrolled in the Sharia Judiciary School attached to the Egyptian Ministry of Education. There, he earned a certificate of specialization in Islamic Sharia in 1927, after which he returned to Nablus to teach Arabic and Islam at al-Najah National University between 1928 and 1929. However, upon the eruption of the al-Buraq Uprising in Jerusalem in August 1929, al-Sayih began his anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist activism from Nablus.

The Emergence of a Young Organizer

In the tumultuous late 1920s and early 1930s, al-Sayih focused his political efforts on organizing in Nablus. He was part of a group in 1929 that formed a secret society in the city to “alter people to the dangers of Zionist ambitions in Palestine and to encourage them to fight British imperialism.”3 He subsequently took part in the “Nablus Conference for Arming the Arabs and Dealing with the Problem of the Jews’ Acquisition of Weapons” held on August 1, 1931, in Nablus, during which the city notables protested Britain’s collaboration with the Zionists. The conference also proclaimed the adherence of the Arab Executive Committee to a policy of peaceful protest.

Two years later, al-Sayih became a supporter of the Independence Party of Palestine, hizb al-istiqlal in Arabic, which formed on August 13, 1932, as an Arab nationalist party. While he did not officially join it, he gave speeches at its meetings. The short-lived party proclaimed that the principal enemy of the Palestinians was British imperialism; therefore, it called for a struggle not only against the Zionists, but the British as well.

Shortly thereafter, al-Sayih took part in founding the Society of Muslim Youth in Nablus.

Al-Sayih’s religious expertise earned him accolades, including from Hajj Amin al-Husseini, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and leader of the Supreme Muslim Council. In 1930, al-Sayih was chosen as the chief of the registrars of the sharia court in Nablus, and in 1935, he was appointed judge of the court.4 In April 1936, al-Sayih was selected to head the fundraising subcommittee of the Nablus branch of the countrywide committees formed to organize the general strike that paved the way for the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936–39. Due to his role in organizing the strike in Nablus, British forces arrested al-Sayih in September 1937 and held him for nine months in the city of Acre before exiling him for one year to the town of al-Bira.5

Following his release, al-Sayih was assigned to serve as the secretary-general of the Supreme Muslim Council, a position he held until late 1940, when he began his most illustrious and long-standing position as a judge in Jerusalem, first in the sharia courts until 1945, and then in the city’s sharia appeals court until 1948. In the aftermath of the Nakba, the partition of Jerusalem and the annexation of its eastern side by Jordan, al-Sayih was appointed head of the sharia appeals court and chief of the courts throughout the West Bank. When the east and west banks were formally united in April 1950, al-Sayih was also chosen as head of the sharia appeals court in Jordan and a member of the Council of Waqfs and Islamic Affairs, which oversaw Jerusalem waqfs, charitable endowments under Islamic law that are held in trust.6

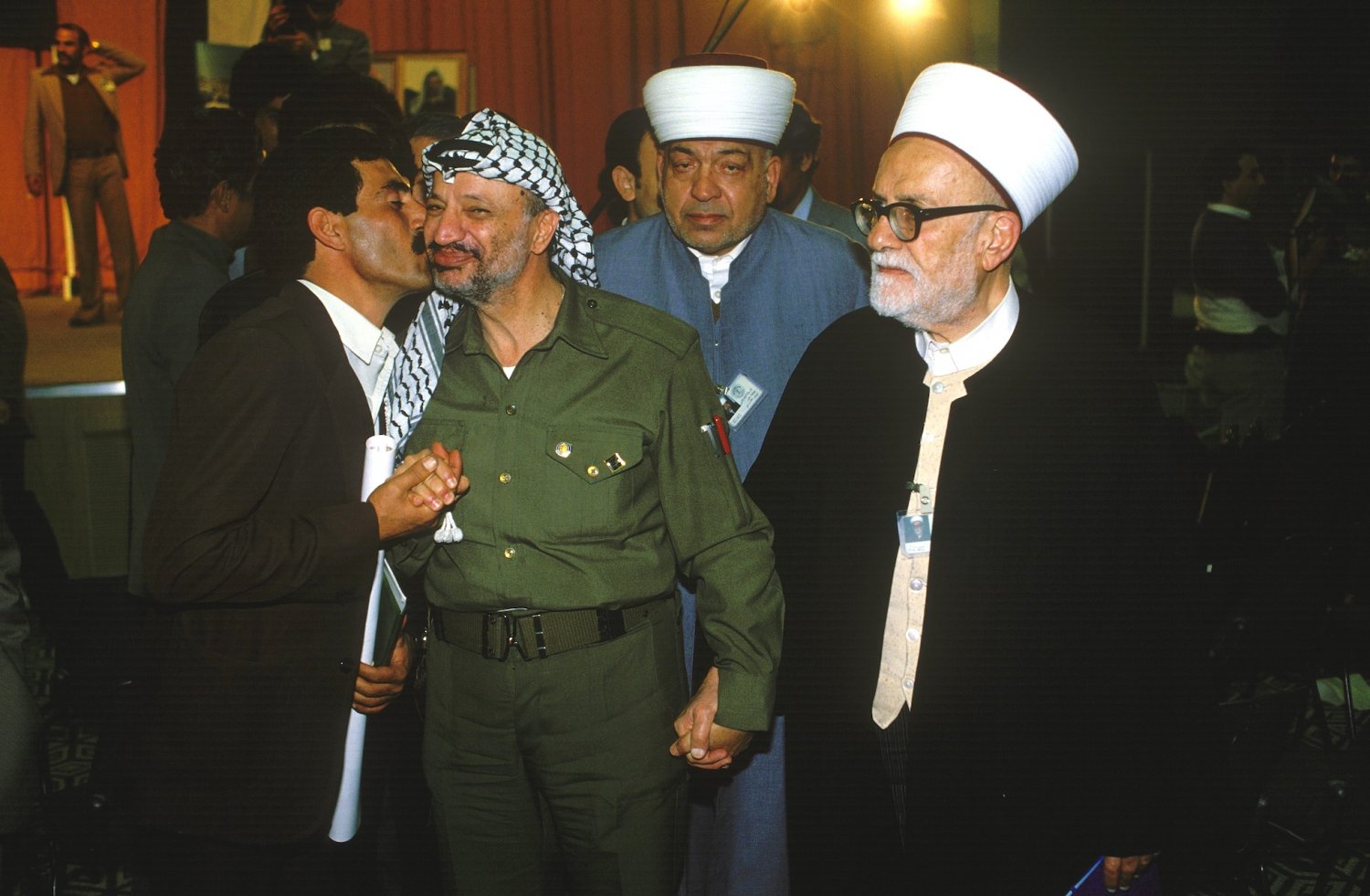

Al-Sayih continued to serve in these important positions throughout the years of Jordanian rule over Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank. Indeed, he was also a member of the historic Palestine National Council (PNC) meeting that convened in Jerusalem over several days starting on May 28, 1964. On June 2, at the end of the meeting, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was established as the representative of the Palestinian people. Throughout his tenure as a leading member of the organization, al-Sayih maintained warm relations with its leadership, including Yasser Arafat.7

Confronting the Israeli Occupier

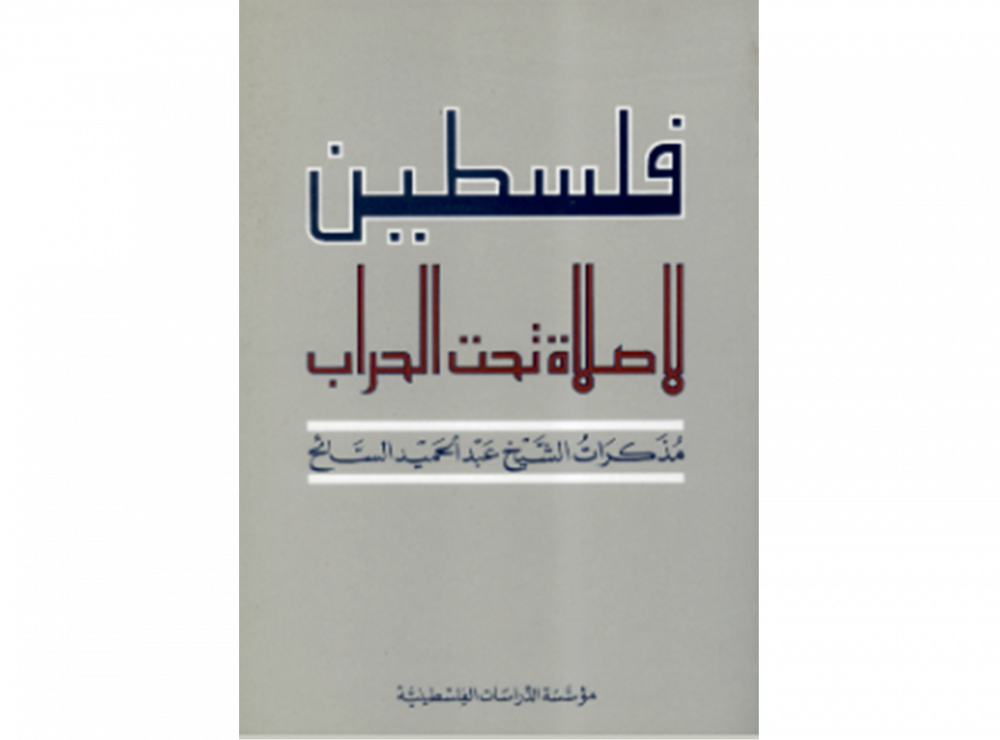

Al-Sayih did not shy from confronting Israeli occupation authorities after they occupied Jerusalem in June 1967. The rather dramatic exchanges he had with different Israeli figures in the aftermath of the city’s capture, which led to his banishment from Jerusalem in September, are retold in detail in his memoir, Palestine: No Prayers under Bayonets: The Memoirs of Sheikh ‘Abd al-Hamid al-Sa’ih, that was published in 1994 by the Institute for Palestine Studies.

Eyewitness to a Transformative Period

The following excerpts from al-Sayih’s memoir, translated from Arabic by Alex Baramki, depict a unique time in Jerusalem’s history.8 Under Jordanian rule from 1948 to 1967, East Jerusalem and Jordan’s capital of Amman were very much interconnected geographically, politically, and culturally—both serving as hubs of Palestinian liberationist mobilization. Al-Sayih’s reflections on his experiences in the immediate aftermath of the city’s capture in June 1967 are a vivid testament to this turbulent period in Jerusalem’s history when the Israeli occupation of Jerusalem was not yet a foregone conclusion, and thus, the possibility of liberation from the Zionist yoke was palpable among its united Palestinian and Jordanian Arabs:

At the time of the 1967 hostilities, I was president of the Shari‘a Court of Appeal, with an office in Amman and another in Jerusalem. Every Monday morning I would travel from Jerusalem to Amman, remain there until Wednesday, and then return to Jerusalem. At one point, Shaykh Muhammad Amin al-Shanqiti, then Jordan’s chief justice, had attempted to interfere with this arrangement, requesting that I reside permanently in Amman. I refused and complained to Prime Minister Sa‘id al-Mufti, who told me to ignore him.

On Monday, 5 June 1967, just as I was beginning the day’s work at the courthouse in Amman, we began hearing reports that Israel had launched its aggression. I received a telephone call from my home in Jerusalem asking that I return immediately because the shelling had reached our neighborhood. I left work at once, asking my personal driver to take me and Shaykh Hilmi al-Muhtasib, a fellow member of the Shari‘a Appeal Court, back to Jerusalem. En route, at Azariyya, a village on the outskirts of Jerusalem, the Jordanian army stopped us, saying there was terror bombing everywhere. Using an army telephone, I called my house in Jerusalem and was told not to come because the shelling was intense and all the neighbors were gathered in our basement, using it as a bomb shelter. During the two days I spent in Azariyya, I spoke to some of the soldiers who were wandering aimlessly about, and was pained to hear from them that resistance had collapsed and the soldiers couldn’t hold their ground because their superiors had left.

When the air strikes reached Azariyya, I managed to get a ride to Jericho, where I found my own driver who had gone off with the car. I got a room at the Hisham Palace Hotel, worrying the entire time about my family and wondering how I could reach them. In the meantime my son Bassam, who had learned where I was, arrived and told me that the Jews had come to our house in Jerusalem and demanded that the family either leave the house or stay put and not go out. They preferred to leave, even though my wife and son Qadri were unwell, and since there was no other transport went on foot under bombardment as far as Khan al-Ahmar, where they found a truck to take them to Jericho and my hotel. There we remained, waiting all together.

First Encounters with Occupation Authorities

On the third day, Israeli planes dropped flyers stating that it was futile to resist and calling on people to surrender. Soon after the Israeli army arrived at Jericho unimpeded. Jewish soldiers came to the hotel, but I avoided them until the military commander summoned us to inform us that the town was occupied and that no movement was allowed. I remained in Jericho with my family several days longer until a car arrived from Jerusalem with a certain Abu Jarir, who introduced himself as an Arab from Nazareth married to a member of the al-Muhtasib family and who worked for Israeli broadcasting. He was accompanied by Hassan Tahboub, director of Jerusalem’s Awqaf Department and representatives of the Israeli military command. They told me that the military governor general of Jerusalem wanted to see me. I said my family was with me and that I could not leave without them, so they brought a large car and we all returned to Jerusalem together. Once there, they asked me to go to the military headquarters to see the governor general. I asked that Shaykh Hilmi al-Muhtasib, my colleague on the Shari‘a Court of Appeal, Shaykh Sa‘adeddine al-Alami, the mufti of Jerusalem, Shaykh Sa‘id Sabri, the qadi of Jerusalem, and Hassan Tahboub all accompany me, which they did.

We met first with an aide of the governor general, an Arab, who briefed us about the impending meeting. He told us that the Israeli commander would greet us and give us a proper welcome, and asked that we reciprocate and be cooperative. When we were ushered into the commander’s office, he read us a prepared speech that included the following statement: “We were forced against our will to enter this war. Jordan had attacked Jewish centers in Jerusalem.” After requesting that I call the people to Friday prayers the next day so that life could return to normal, they asked me, with the tape recorder running, to speak. I declined and asked Shaykh Sa‘adeddine to speak instead. He did so, avoiding any reference to politics but asking instead for relief supplies and for food for the orphans. His words displeased them, and they turned off the tape recorder. At that point, with the tape recorder off, I began to talk. I said Jordan did not attack anything, and that the Jews in any case had no centers in [East] Jerusalem. As for the commander’s request that we summon the people to Friday prayers, I said that it was not permissible for us to pray with weapons pointed at us, and that I would not call people to prayers so long as their soldiers remained on sacred ground. I ended the discussion, resolutely sticking to my position, and left with my companions. Abu Jarir, the Arab from Nazareth, ran after me, asking, “Why did you do this?” I replied, “I want to deal with them candidly from the very first day.”

When the Israelis saw my resolve, they did remove the troops [from the esplanade of the Haram al-Sharif], whereupon I instructed those responsible to proclaim from the minarets that Friday prayers would be offered at the al-Aqsa mosque the next day. This was done, and after the Friday prayers I was taken home in a car belonging to the occupation authorities. After lunch they ordered me to go to Jericho. I asked if they wished to take possession of my house, and they said no, but when I went with my family to Jericho I left my son Bassam behind to look after the place. Although I did not discuss the matter with the authorities, I suspect that I had been sent to Jericho as punishment for refusing to be recorded; I had not wanted to say anything that could be exploited and propagated. At all events, after a few days they notified my son Bassam that they had no objection to my returning to Jerusalem. Upon my return I ordered the Shari‘a Court of Appeal to open and resume its functions. Immediately thereafter, I was summoned by the Israeli minister of religious affairs, Dr. Zerach [Warhaftig]. At my request, the meeting was also attended by Shaykh Hilmi al-Muhtasib, Shaykh Sa‘id Sabri, Shaykh Sa‘adeddine al-Alami, and Hassan Tahboub.

The following dialogue took place between us and the Israeli Minister of Religious Affairs, the latter speaking through an aide who knew Arabic:

Minister: Welcome. I am ready to listen to your requests and desires, and will consider them.

Myself: We thank you for your welcome. We did not ask to meet with you. Rather you asked to meet with us, and we are ready to listen to your requests and desires, and will consider them.

Minister: That’s good, too. I wish to discuss three matters:

1) The Shari‘a Court of Appeal and its regulatory system, so it may function;

2) the Shari‘a Court of Jerusalem, and the measures that need to be taken for it to function;

3) the Department of Religious Endowments, and putting in place a regulatory system for it, to enable it to function.

Myself: The Shari‘a Court of Appeal is established and functioning.

Minister: On what legislative basis are you functioning? What laws are you applying?

Myself: In accordance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention[s], we are applying Qur’anic law and Jordanian legislation.

Minister: What does the Geneva Convention state?

Myself: It states that under occupation the judiciary apparatus of the occupied territory is to remain in place and continue to apply the laws it had been applying prior to the occupation.

Minister: Why don’t you apply our laws?

Myself: Your judiciary law stipulates that before a judge can exercise his powers he has to appear before the head of state and pledge loyalty to the state. We tell you frankly that we have no loyalty to you, because you have occupied our lands and violated our rights, and the Qur’an forbids us to enter into a contract of clientage with you . . .

Minister: In this case, you must resign your positions.

Myself: And to whom do we submit our resignations?

Minister: To us.

Myself: We do not recognize that you have any rights except those of the occupier. It is not your business to meddle with our courts and Islamic affairs. If we wish to resign, we will submit our resignations to King Hussein.

Minister: And who will pay your salaries?

Myself: We want no salaries from you, nor anything else.

The minister then asked about the Shari‘a Court of Jerusalem, so I referred him to Shaykh Sabri, the presiding judge.

Shari‘a judge: We stand behind all that the President of the Court of Appeal has said.

Minister: What about the Department of Religious Endowments?

Awqaf Director: The Department of Religious Endowments is functioning as it was prior to the occupation. It never ceased to function.

Minister: I will present a report to my government, to take the necessary measures.

With that, the meeting came to an end.

One of al-Sayih’s most political moves was the formation of the Higher Muslim Council with other Jerusalem notables in July of 1967. The council’s main objective was the protection of Jerusalem’s Muslim holy places and the management of all Islamic affairs, including religious courts and waqfs in the city and the rest of the West Bank so long as the occupation continued. The council appointed al-Sayih Chief Judge of the West Bank and delegated the sharia appeals court in Jerusalem to assume the responsibilities of the Council of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs, and of the Committee for the Refurbishment of al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock in the West Bank.

As the late Palestinian nationalist Ibrahim Dakkak described it: “This put the occupation authorities in an awkward position since that decision was taken independently of the Jordanians despite the fact that Shaykh Abdul Hamid [al-Sayih] and the council staff were Jordanian civil servants.”9 Al-Sayih and his compatriots’ flagrant disavowal of Israel’s occupation of Jerusalem—indeed, this threat to Israeli rule over Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank—brought al-Sayih under intense Israeli scrutiny, leading to his exile from the city in September. The following excerpts from al-Sayih’s memoir depict this turbulent summer in Jerusalem and the road to his exile:

The Establishment of the Higher Muslim Council

Shortly after the meeting with the minister, a Muslim acquaintance who resides in the territories occupied in 1948, contacted me to inform me that the occupying authorities were about to pass legislation empowering them to seize the registers of the Shari‘a Court of Jerusalem as well as the records and deeds of the Awqaf Department. The records in question are precisely those that establish our relationship to Jerusalem and indeed to the whole of Palestine. It is well known that a high proportion of Palestinian territory is waqf property, and the Shari‘a court records of Jerusalem, the written evidence of land transactions, date back to the eighth century Hejira [thirteenth century C.E.], hundreds of years before the establishment of Palestine’s [civilian] Land Registry Department. These records constitute the most important resource we have for documenting our ownership of the land.

It was therefore imperative to foil the intentions of the occupying power. To this end, I began poring over Islamic legal texts in search of a way out. In the course of my research, I came upon a law stating that if non-Muslims committed hostilities against Muslim lands, the Muslims must assemble and elect from amongst themselves persons who would govern their affairs and regulate matters pertaining to their properties. I began contacting fellow notables of good sense and judgment with a view toward forming such a body, doing so secretly to prevent the enemy from discovering the plan and nipping it in the bud . . .

I explained to the group why I had called the meeting, recounting the interview with the Israeli minister of religious affairs and the measures that the occupying authorities were planning to take. They asked what we could do in this situation, with our country being occupied by force. I emphasized the dangers that would ensue if the enemy got hold of the Shari‘a court records and the Awqaf registers, since these documents constitute our sole means of establishing our rights in Palestine not only with regard to the awqaf but for other matters as well. Indeed they constitute the sole recourse for establishing rights concerning religious endowments and related sales and commercial transactions not only for Muslims, but also for Christians and Jews. Upon hearing all this, some of those present asked what I proposed. After further deliberations, I told them about the piece of Islamic jurisprudence I mentioned earlier, and they all agreed that we should use it as the basis of our position. We then formed a committee from among the lawyers present, and the following statement was drafted to be sent to the military governor of the West Bank. In addition to announcing the formation of the Muslim leadership body, the statement also condemned the annexation of Arab Jerusalem that had occurred several weeks earlier and enumerated the ways in which the occupying authorities were interfering in Islamic religious affairs.

The Memorandum to the Israeli Authorities

Whereas a state might occupy territory belonging to another state, the nature of the occupation does not grant the occupier sovereignty over the said territory. Rather, the activities permitted to the occupying state are restricted to observing the interests of the occupied territory and respecting the laws in force therein, in addition to respecting the lives, rights, and property of its inhabitants. The occupying state is also obliged to protect their freedom of religious belief and worship.

We hereby declare that the decisions issued by the Israeli legislative and administrative authorities to annex Arab Jerusalem and its hinterland to Israel are null and void, for the following reasons:

1. Arab Jerusalem is an integral part of Jordan, and by virtue of the provisions of Paragraph 4 of Article 2 of the United Nations Charter, Israel is prohibited from violating the integrity and political independence of Jordanian territory, and consequently is prohibited from annexing any part of Jordanian territory.

2. The United Nations has ruled the annexation of Arab Jerusalem to Israel to be illegal in its resolutions passed at the special emergency session held between 17 June 1967 and 21 July 1967.

3. The Israeli Knesset has no authority to annex the territory of another state.

4. We also declare that the people of Arab Jerusalem and its surrounding areas, together with the other inhabitants of the West Bank, enjoyed complete freedom of choice when they opted for union with the East Bank, thus forming the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan by virtue of the unanimous decision of the Jordanian National Assembly on 24 April 1950.

We hereby record that the annexation of Arab Jerusalem is an invalid measure taken unilaterally by the occupation authorities against the will of the inhabitants of the City, who reject this annexation and insist on continued unity of Jordanian territory.

At the same time, we observe that the Israeli occupation authorities have begun to interfere in Muslim affairs in ways that are both illegal and incompatible with the provisions of the Islamic religion. Examples of such interference are as follows:

1. Censorship of the Friday Sermon at the Aqsa Mosque by the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs. Many passages were deleted from these sermons, including verses from the Qur’an.

2. Israeli male and female visitors have been allowed to enter the Aqsa Mosque immodestly attired, offending both the principles of religion and Arab and Islamic custom.

3. The demolition by the Israeli authorities of two mosques along with the entire Moroccan Quarter of Jerusalem, the entire quarter being waqf property.

4. The violation of the Sanctuary of Abraham in Hebron, which has been closed to Muslims except for a few hours on Friday while Israelis enjoy free access to it throughout the week for the performance of rites offensive to the precepts of the Islamic Religion.

5. Interference in Islamic Waqf affairs by the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs.

6. Seizure of the waqf land known as “al-Nazir” situated on the road to the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, and the disposal of this land for their own purposes without the knowledge of the Waqf authorities and in violation of waqf interests.

7. Attempts by the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs to interfere in the affairs of the Shari‘a courts, including the Shari‘a Court of Appeal in Jerusalem.

In view of the above, we demand the following:

1. No violation of the territorial integrity and political independence of Jordan, and respect for the United Nations Charter, the provisions of international law, and the resolutions adopted by the United Nations at its last session that ruled Jerusalem’s annexation as illegal, and, consequently, the abrogation of the decision to annex Jerusalem and its outskirts to Israel.

2. No further interference in Muslim religious affairs, including matters of personal status, Shari‘a jurisdiction, and affairs connected with preaching and guidance; respect for religious feelings and the inviolability of the holy places; and no infringement on Islamic Waqf properties.

3. Respect for Arab juridical, legal, administrative, municipal, and other institutions in Jerusalem, which must be allowed to exercise their prerogatives as they did before the occupation.

Inasmuch as Islamic jurisprudence explicitly stipulates that Muslims must control all their religious affairs in circumstances like those prevailing at present, and forbids non-Muslims from taking charge of Muslim religious affairs, we, the representatives of the Muslim citizens of the West Bank, including Jerusalem, met today in the hall of the Shari‘a Appeal Court in Jerusalem. After a discussion of Islamic affairs and an exchange of views on all matters concerning religious rites, practices, the holy places and Islamic affairs, we have agreed:

First, to regard the undersigned as constituting a Higher Islamic Council charged with managing the Islamic (religious) affairs in the West Bank, including Jerusalem, until the occupation comes to an end; and

Second, the aforementioned body, thus constituted, resolves the following:

1. To invest His Eminence Shaykh Abd al Hamid al-Sayih with the authority of Chief Qadi of the West Bank, in accordance with the provisions of Jordanian Law.

2. To empower, in accordance with the provisions of Jordanian Law, the Shari‘a Court of Appeal in Jerusalem to exercise all the prerogatives of the Council of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs and of the Committee for the Refurbishment of the Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock in the West Bank and also to exercise all the prerogatives granted to the Awqaf director general.

3. To empower His Eminence Shaykh Hilmi al-Muhtasib to exercise the prerogatives of the Director of Shari‘a Affairs, in addition to his functions as a member of the Shari‘a Court of Appeal.

4. To make His Eminence Shaykh Sa‘adeddine al-Alami, Mufti of Jerusalem, a member of the Board of the Shari‘a Appeal Court, in addition to exercising present functions.

5. To include His Eminence Shaykh Sa‘id Sabri, Qadi of Jerusalem, in the Council of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs and in the Committee for the Refurbishment of the Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock.

6. The above authorities shall exercise their powers and prerogatives on the West Bank, including Jerusalem, in accordance with Jordanian Law, until the occupation comes to an end.

The statement, which was dated 24 July 1967, was addressed to the Israeli military governor and was signed by all the persons, mentioned above, who participated in the meeting that led to the drafting of the statement.

In addition to dispatching the statement to the Israeli Military Governor of the West Bank, we had it broadcast by the radio stations of Amman, Damascus, the Voice of the Arabs [Sawt al-Arab], and others, causing tremendous reverberations in the Arab world, Israel, and internationally. Indeed, the statement was considered the harbinger of the Palestinian resistance, and after it was broadcast and news of it spread, petitions of support and endorsements began pouring in. Some were brought in by delegations of men and women, and copies of these statements of support were sent to the military governor. Several dozen of these were published by the Institute of Palestine Studies in 1967 as part of its documents series; the Jordanian Ministry of Information also published them in “Jordanian Documents 1967.”

There is no need to point out that just as Muslims and their Christian brethren had previously stood side by side as one people in resisting the British occupation, they now took the same stance in resisting Israel’s occupation in 1967 of what remained of their country. This solidarity was well illustrated in the messages of support that reached me when we announced our intention to resist the occupation and established the Higher Islamic Council of Jerusalem. Among those who sent us such support messages was Bishop Iliya Khoury, head of the Anglican community, who was later banished for it and eventually became a member of the Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization. The bishop did not confine himself to writing, but personally led a delegation to declare his endorsement and support. Hilarion Capucci, Archbishop of the Greek Catholic church, was also among the endorsers and supporters. He aided and supported the Palestinian revolution in many ways until the occupying authorities deported him.

Dealings with the Israeli Minister of Religious Affairs

During this period, I had no official contact with the Jordanian government, since the occupying authorities were keeping close watch on me and preventing any communication—to such an extent that when an international fact-finding committee asked to meet with me, the Israeli authorities said I was unavailable. When that same international committee met with Anwar Nusaybeh and asked him about matters relating to religious endowments and the Shari‘a courts, he told them that such inquiries should be addressed to me, whereupon the committee members informed him of the authorities’ statement that I was unavailable. Nusaybeh assured them that I was in my office at that very moment. They immediately summoned me and I gave them my testimony. After this incident, the Israeli minister of religious affairs asked to meet with me in the aim of organizing a social gathering at the King David Hotel to introduce me to the Shari‘a judges from the Palestinian territories occupied in 1948, along with some other personalities. I excused myself from meeting him on the grounds that I was busy from morning until night. The Shari‘a judges from the 1948 territories also said they were unable to attend because of other commitments. When the Israelis said the Shari‘a judges wished to meet me directly, I said they were welcome to come to my house.

Around this time a messenger came to inform me that the Israeli minister of religious affairs, Dr. Zerach [Warhaftig], wished to “return my visit.” I responded that I would give him an appointment at my convenience. I duly did so, and he came to see me at the courthouse.

During our discussion, I spoke to him about Islamic jurisprudence, and noted that its observance required ruling against Muslims in favor of non-Muslims, even if there was enmity and hatred between them, if the case so merited. To make my point, I showed him the record of a case where I had ruled in favor of the Custodian of Enemy (Jewish) Property against the Mutawali (trustee) of Islamic Waqf properties, of one of Jerusalem’s oldest and most venerable Muslim families, in so doing overturning a judgment by the Shari‘a court of Jerusalem. In brief, the case had been brought before the Shari‘a court by Shaykh Abdul-Mu’ti al-Alami, the mutawali of the al-Alami family awqaf. Alami claimed that a family ancestor had entered into a “hikr” (long lease) arrangement with a Jew, whose descendant was represented by the Custodian of Enemy Property, concerning a plot of Alami waqf land for the purposes of building or cultivation. Since the land had been neither cultivated nor built upon, Alami asked the judge to cancel the “hikr” agreement and return the land to the family waqf. The Custodian of Enemy Property having conceded that the land in question had neither been cultivated nor built upon, the Shari‘a court judge had ruled for Alami. The Custodian of Enemy Property then appealed the ruling, and as I was president of the Shari‘a Court of Appeal, it fell to me to review the case. Upon studying the facts, it became apparent to me that the judge had misruled, since he had not given the Custodian the opportunity to pay the arrears in rent owed for the waqf property; if he had done so, and if appropriate back revenues had been collected, the interests of the family waqf would have been safeguarded under Shari‘a law. I therefore revoked the ruling and referred it back to the Shari‘a court to apply the decision. And in fact there was a retrial, and my ruling was upheld. The Custodian was indeed prepared to pay the appropriate rent, which was duly collected and the mutawali’s case was dismissed.

The Israeli minister then asked me, “Did you restore the land to the Custodian of Enemy Property?” I said yes. He then asked, “In accordance with what authority did you make your ruling?” “In accordance with the Qur’an,” I replied. He then asked me what the Qur’an said, and I replied, “It says, ‘. . . and let not hatred of any people seduce you that ye deal not justly. Deal justly, that is nearer to your duty . . . .” (Surah V, The Table Spread, verse 8). At this the Israeli minister respectfully stood up. He asked me for a copy of the ruling, which I gave to him. With that our relationship ended, on account of my refusal to submit our rulings and decisions to Israeli authorities.

Deportation

Indeed, the occupying authorities continued to use all possible means, both enticements and threats, in their efforts to get me to obtain from them prior approval for appointments, promotions, transfers, and other decisions we were making and measures we were instituting in the religious courts and Department of Religious Endowments. They would repeat their demands, and I would reiterate that according to the Fourth Geneva Convention, whose terms I would cite, Israel was an occupying power without sovereign rights.

Their last attempt came when I was summoned to appear before the deputy military governor-general, in the presence of Major David Farhi, the military governor’s liaison officer with the Arabs. When they again asked that we come to an understanding, I said, “We can come to an understanding on the basis of your leaving our country and handing it back to us. Without this, there is no way we can come to an understanding.”

“From where do you derive your authority?” they asked. I replied, “I base myself in my work on Islamic jurisprudence, which states that when you or anyone else occupies our country, then it is incumbent on Muslims to select someone from their number to manage their affairs, and they chose me.” In response, he asked, “And who selected you? We have information that you were chosen by a small number of people.” I replied, “I was selected by notables, deputies, magistrates and official Islamic personages. After that delegations came from all quarters, making pledges of allegiance and support; copies of these have been sent to you. In any case, if there is anyone who is unhappy with my leadership, I am prepared to hand it over to that person and to cooperate with him.”

He then said, “We do not oppose you. We offer and will give you support.” I said, “I will not be satisfied until you leave the country and give it back to its people. That is my only request.”

After several days—actually, at about three o’clock in the morning of 25 September 1967—there was a knock on my door. When I emerged I was told, “You have to go to see the authorities in order to answer a question, and then you can return.” I asked whether I should pack a bag, and they said no. I got a small bag, just in case, and packed pajamas and a towel. I was then taken to the Russian compound, where an official rose to his feet to greet me respectfully and offered me coffee or tea. I declined, saying that I wished to pray, as it was time for dawn prayers. After I finished my prayers he handed me the order of deportation. Written in Hebrew, it stated that Moshe Dayan, who was defense minister at the time, has decreed my deportation in accordance with article such and such of the emergency regulations. After they gave me the deportation order, they took it back and replaced it with an Arabic translation, saying that since I was going into enemy territory, I should not be carrying a document written in Hebrew.

I was then driven straight to the Allenby Bridge in a small car, without stopping by my house. I asked why I had not been told that the matter involved deportation so that I could at least have brought some personal belongings. They said I should draw up a list of what I wanted, and said that they would send whatever I requested through the Red Cross. They indeed did so, as promised.

Thus was I banished from Jerusalem and my country, becoming the first to suffer this fate. Shortly afterwards the occupying authorities deported the renowned attorney Ibrahim Bakr, who became the second. Deportations then followed one after the other until they included my friend Ruhi al-Khatib, mayor of Jerusalem, and many others. Deportation is the worst punishment one can suffer, particularly for a Muslim Arab. Yet we have the example of our Prophet; in the end, right triumphed over those who forced him to leave his home in Mecca.

The leaders of Jerusalem, both Muslim and Christian, hastened to send letters protesting my deportation to Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol. Copies were sent as well to Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan and to U Thant, the Secretary General of the United Nations.

Years in Exile, Retirement, Death, and Legacy

Following al-Sayih’s deportation, Israeli occupation forces continued the practice of exiling Palestinian political leaders from Jerusalem. As historian Ann Lesch argues, “From September 1967 until early 1970 . . . Organizers of protests against the annexation of East Jerusalem to Israel and activists in petitions and strikes against changes in the religious, educational and legal systems were singled out for banishment.”10 She goes on to list prominent Jerusalemites who were deported from the city by number:

President of the Islamic Council, Sheikh ‘Abdul-Hamid al-Sayih (no. 1); the mayor of Jerusalem, Rouhi al-Khatib (no. 8); the director of the Maqasid Islamic charitable hospital, Dr. Nabih Mu’ammar (no. 134); the Director of the Arab Land Bank, Anton ‘Atallah (no. 5); and a trade union leader, Michel Sindaha (no. 318).11

Al-Sayih’s leadership during this period, whether in Jerusalem or Amman, was critical to sustaining the efforts of the forcibly fragmented Palestinian nationalist movement that was gradually being erased from Jerusalem. Indeed, it was his ongoing resistance while in exile to Israeli suppression of Palestinian presence in Jerusalem that played a significant role in securing Muslim authority in the city.

Exile in Jordan didn’t stop al-Sayih from centering Jerusalem and Palestine in his political work. On October 7, 1967, within two weeks of arriving in Amman, al-Sayih assumed the role of Minister of Waqf and Islamic Sanctuaries (of Jerusalem) within the Jordanian government—a position he held until December 1968 and then again from June to September 1970. He was also appointed as Chief Judge and lectured as part of the sharia faculty at the University of Jordan. In February 1968, al-Sayih played a central role in organizing a conference in Amman, out of which was formed a permanent committee to save Jerusalem.12

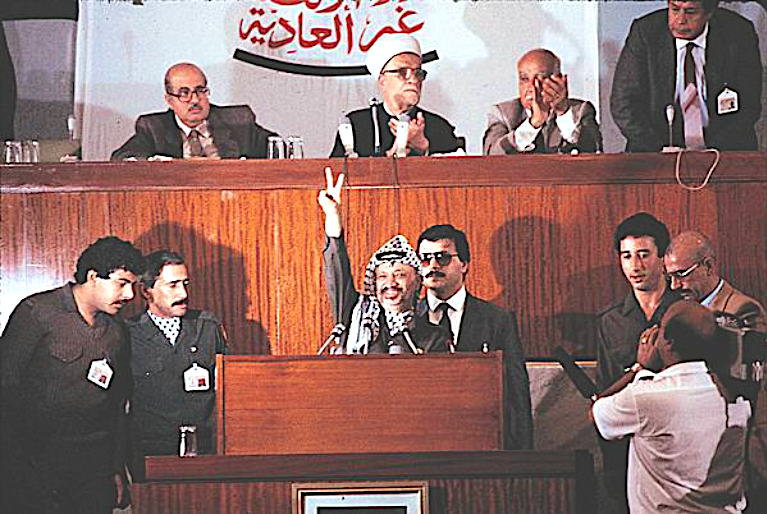

In November 1984, during the 17th session of the PNC meeting, the largest decision-making body of the PLO, al-Sayih was elected president, replacing Khalid al-Fahum. He held this position until his resignation and retirement in 1993 at age 86.

Al-Sayih spent the remaining years of his life in Amman, out of the political limelight, until his death there on January 8, 2001.13 The PLO’s diplomatic mission in Amman requested that al-Sayih be buried in Jerusalem, as per his will.14 In a 2019 interview, al-Sayih’s son Bassam described how Jerusalem never left his late father’s mind for a moment, and that it was his dying wish to be buried in the city. Bassam managed to bring his father’s body to the city, first visiting his home, then the al-Aqsa Mosque, and finally, into the earth.15

Born in Nablus in 1907, al-Sayih died in exile in Amman at the age of 94 having lived through and witnessed every significant moment in 20th-century Palestinian history, from the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the 30-year British Mandate to the Nakba, the Naksa, and the First Intifada. His extensive writings reflecting on these tumultuous events constitute a critical record of Palestinian resistance and of Jerusalem as a space for nationalist politics before and after it was occupied in 1967.16 Moreover, his work indicates the extent to which Amman served as a critical site of Palestinian political mobilization after Jordan lost East Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank in the war. Indeed, al-Sayih served in different leadership roles in the Palestinian nationalist movement while in Amman, the hub of many initiatives dedicated to saving Jerusalem and Palestine.

Al-Sayih is remembered as a Palestinian nationalist, religious cleric, and devoted activist to the liberation of Palestine. His long and illustrious career fighting to defend Palestinian rights and liberation from British then Zionist occupation started in Nablus, centered in Jerusalem, and ended in Amman. His commitment to protecting Jerusalem’s Palestinian and Muslim identity earned him great admiration among Palestinians and Jordanians who refer to him as the “Red Sheikh” due to his progressive political principles and resilience in the face of injustice.

He earned a series of awards throughout his expansive career, the most prestigious of which Mahmoud Abbas, president of the Palestinian Authority, awarded him postmortem on November 22, 2013. The Medal of the Star of Honor, as the award is named, was given to al-Sayih in appreciation of his role in

all stages of the Palestinian revolution, his keenness for independent Palestinian national decision-making through his positions and writings, and his efforts to preserve the position of the Palestine Liberation Organization as the sole legitimate representative of our Palestinian people through his important role as President of the Palestinian National Council.17

Al-Sayih is survived by three daughters, Nawal, Na’ila, and Basima, and three sons, Qadri, Usama, and Bassam, from his wife, Fadliyya Bakri.18

Selected Works

Principles of the Islamic Religion. [In Arabic.] Amman: Ministry of Education, 1964.

The Way of Islam. [In Arabic.] Jerusalem: The Office of Education Affairs, 1966.

The Status of Jerusalem in Islam. [In Arabic.] Amman: The Committee to Save Jerusalem, 1969.

What Is to Follow the Burning of al-Aqsa Mosque? [In Arabic.] Cairo: Dar al-Sha‘b, 1970.

Islamic Education. [In Arabic.] Jerusalem: The Office of Education Affairs, 1972.

The Palestinian Intifada: Its Future and Role in Liberation. [In Arabic.] Amman: The Center for Middle East Studies, 1991.

Sources

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. Accessed April 16, 2024.

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih: Exiled, Minister, Sheikh!” [In Arabic.] Fatehwatan, January 9, 2012.

Agence France-Presse. “Abdel Hamid al-Sayeh, Palestinian Cleric.” New York Times, January 15, 2001.

“Jerusalem 1967.” Journal of Palestine Studies 37, no. 1 (2007): 88–110.

“Learn about the Journey of Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih, the First Palestinian to Be Exiled from His Homeland after the 1967 Occupation.” [In Arabic.] Alghad TV, March 21, 2019.

Lesch, Ann M. “Israeli Deportation of Palestinians from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, 1967–1978.” Journal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 2 (1979): 101–31.

al-Sayih, Abd al-Hamid. Palestine: No Prayers under Bayonets: Memoirs of Sheikh ‘Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih. [In Arabic.] Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2001.

“al-Shaykh Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.” [In Arabic.] WAFA: Palestinian News & Info Agency. Accessed April 16, 2024.

Tamari, Salim. “Interview with Ibrahim Dakkak (1929–2016): A Life of Struggle for Palestinian Rights.” Journal of Palestine Studies 46, no. 2 (2017): 83–90.

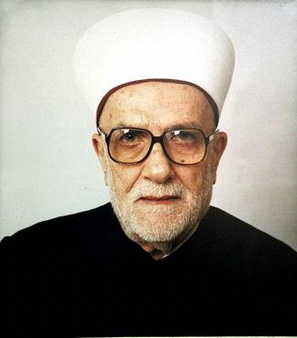

[Profile photo: Courtesy of PalQuest]

Notes

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih,” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, accessed April 16, 2024.

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.”

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.”

“al-Shaykh Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih” [in Arabic], WAFA: Palestinian News & Info Agency, accessed April 16, 2024.

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.”

“al-Shaykh Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.”

Agence France-Presse, “Abdel Hamid al-Sayeh, Palestinian Cleric,” New York Times, January 15, 2001.

The following translated excerpts from Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih’s memoir, Palestine: No Prayers under Bayonets: Memoirs of Shwikh ‘Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih [in Arabic] (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2001), appear in “Jerusalem 1967,” Journal of Palestine Studies 37, no. 1 (2007): 88–110.

Salim Tamari, “Interview with Ibrahim Dakkak (1929–2016): A Life of Struggle for Palestinian Rights,” Journal of Palestine Studies 46, no. 2 (2017): 86.

Ann M. Lesch, “Israeli Deportation of Palestinians from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, 1967–1978,” Journal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 2 (1979): 108.

Lesch, “Israeli Deportation of Palestinians,” 108–9.

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih: Exiled, Minister, Sheikh!” [in Arabic], Fatehwatan, January 9, 2012.

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.”

Agence France-Presse, “Abdel Hamid al-Sayeh, Palestinian Cleric.”

“Learn about the Journey of Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih, the First Palestinian to Be Exiled from His Homeland after the 1967 Occupation” [in Arabic], Alghad TV, March 21, 2019.

For a list of some of al-Sayih’s publications, see Selected Works.

“al-Shaykh Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.” Translated by Jerusalem Story Team.

“Abd al-Hamid al-Sayih.”