Jerusalem’s Delicate Balance

Credit:

iStock Photo

What Is the “Status Quo”?

Snapshot

Jerusalem’s religious sites are sacred to the world’s three Abrahamic faiths. Exhausted by the discord over control of these sites, mostly among Christian sects, Ottoman officials first regulated their access and administration in 1852. The law was enshrined in international law in 1878 and has since been known as the Status Quo agreement on Jerusalem’s holy sites.

For centuries, Jerusalem’s Old City has been a focal point for confrontations between invaders from, and defenders of, the world’s three Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Over the last two decades, it has become a site of increasingly violent hostilities between Palestinians and armed Israeli forces.

The Old City’s main Muslim holy site, the Haram al-Sharif (in English, the Noble Sanctuary, also referred to by Jews as the Temple Mount in English or Har ha Bayit in Hebrew) has been transformed into a violent flashpoint. In the middle of Ramadan, on April 5, 2023, Israeli security forces were filmed viciously beating Palestinian worshippers who refused to leave the mosque compound so that Jewish extremists could conduct a sacrifice on the grounds to observe Passover. Hundreds of Palestinians were arrested and banned from returning to the holy site, which includes the revered al-Aqsa Mosque.1

These scenes are reminiscent of May 2021, when Israeli police also stormed the compound, destroying precious artifacts, and tear-gassing, beating, and arresting hundreds of Palestinian worshippers.2

Repeatedly, right-wing Jewish settler groups, protected by Israeli police, have entered the compound as part of their Messianic mission of rebuilding a Jewish temple in place of the Muslim shrines (see The History of Israeli Settlement Expansion in and around East Jerusalem from 1967 to 1993).3 During these provocative events, Palestinian worshippers in the compound are often violently restrained by Israeli police, and sometimes even kept locked inside the mosque buildings.4

Such incursions have increased since the December 2022 victory of Israel’s most extreme, right-wing coalition government to date.5 The new government has reiterated the entrenched Israeli position that it will not relinquish control over any part of the eastern half of the city (including the Old City with its holy sites), promising to continue to construct illegal Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem and strengthen what it calls the unified capital of the Jewish state.6

In response, religious and political world leaders have called on the Israeli government to honor the city’s delicate socio-religious balance by respecting the sanctity of non-Jewish holy sites,7 as codified in the long-standing Status Quo agreement on Jerusalem’s holy sites.

Preserving the Balance: The Status Quo Agreement

An Ottoman decree

The Status Quo agreement has its roots in Ottoman legislation from the 19th century. Following disputes among several Christian sects over control of Christian sites in Jerusalem, the Ottoman authorities “issued a series of decrees to regulate the administration of Christian holy sites by determining the powers and rights of various denominations in these places,” the most important of which was the 1852 firman.8 In this decree, Sultan Abdulmejid I ordered Ahmed Pasha, governor of Jerusalem, to regulate Latin, Armenian, Greek, Syriac, and Coptic access to several Christian holy sites in Bethlehem and Jerusalem, including the “Great Church” of Bethlehem (i.e., the Church of the Nativity), as well as the Cupola of the Ascension, located on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.9

While a “Mohammedan temple,” as the sultan called it, the Cupola of Ascension was also a site for both Latin and Greek worship. However, Latins had evidently been preventing Greeks from using the site, to which the sultan objected. He decreed: “The Greeks shall . . . not be prevented from exercising their worship in the interior [of the Cupola of Ascension], on condition that they make no alteration in the present condition of that oratory, and that there shall be a Mohammedan porter at the door, as heretofore.”10 The tradition of entrusting a Muslim from Jerusalem with the keys to sites of Christian worship dates back to the 12th century, when the keys to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem were given to Jerusalem’s Muslim Joudeh and Nusseibeh families.11

These rulings established a general outline for conduct at these key holy sites: that all changes should be mutually agreed between the various religious parties represented at the site, while otherwise maintaining a status quo. It asserted the right of Jews to pray at the Western Wall, which adjoins the mosque compound and was part of the Second Temple, and reestablished a ban on non-Muslims entering the Haram al-Sharif.

While maintaining this balance seeks to prevent religious conflict, it also promotes stasis.

At the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, for example, its three main custodians—the Greek Orthodox Church, the Franciscan Order (known as the “Latins”), and the Armenian Church—took nearly a century to agree together on plans for structural renovations needed to prevent the building’s collapse.12 The actual renovations were completed in only one year.

Author Michael Teller relates the story of a ladder that has been positioned on the side of the Jerusalem church for at least 264 years—any attempt to move it has been quickly amended, for fear of disrupting the delicate status quo.

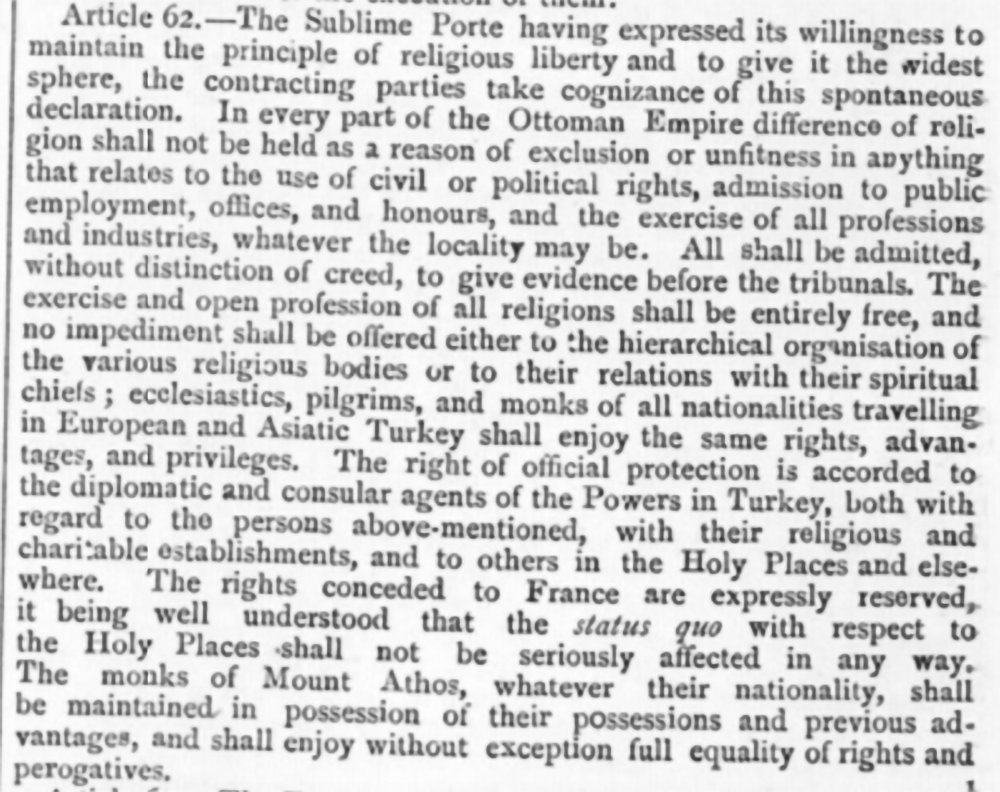

The 1852 Ottoman firman, which became known as the Status Quo agreement, was recognized in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, signed between European powers and the Ottoman Empire. Importantly, Article 62 of the Treaty of Berlin extended the Status Quo to all holy sites in Jerusalem, including Jewish and Muslim sites (see photo). Thereafter, the agreement became binding, a critical and accepted element preserving the balance of power in Jerusalem. As Mounir Marjieh put it:

The Status Quo arrangement is a unique and delicate legal system that contains a specific set of rights and obligations that were created over centuries of practice and are now considered binding international law. It therefore supersedes any and all aspects of domestic law.13

British Mandate rule

British forces ousted the Ottomans from Jerusalem in December 1917. Following a three-year military occupation, Britain was granted its mandate for Palestine by the League of Nations. The administration of this mandate, which officially began in September 1923, was inextricably linked to Britain’s 1917 Balfour Declaration to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine. Henceforth, British Mandate policy in Palestine saw to actualizing this declaration, and Jerusalem was subsequently a center for increasing tensions and hostilities between Palestinian Arabs and Zionist Jews (see The West Side Story, Part 2: The Darkening Horizon: Jerusalem’s New City under the British Mandate).

British Mandate forces in Jerusalem largely turned a blind eye to Jewish provocations of Muslims and Christians (see The West Side Story, Part 3: From Bourgeois Comfort to Untenable Peril: The Emptying of the New City). While they suppressed frequent hostilities, the overall outcome of intercommunal flare-ups in and around Jerusalem was largely in favor of the Jews in line with British Mandate policy.

The delicate balance created by the Status Quo agreement was first toppled by Zionist Jews in 1929 (see The West Side Story, Part 2: The Darkening Horizon: Jerusalem’s New City under the British Mandate). Following years of increasing tensions between Zionists and Palestinians in Jerusalem, including over control of the Western Wall, known in Arabic as the al-Buraq Wall and one of Judaism’s holiest places as the last remaining outer wall of the ancient Jerusalem temple—Zionists staged a demonstration at the site, carrying the Zionist flag and claiming it as Jewish property. The site was recognized as Muslim in the Status Quo agreement, and the al-Buraq demonstration that day sparked a week-long uprising by Palestinians that resulted in the deaths of over 200 people, both Jews and Muslims (see The Destruction of Jerusalem’s Moroccan Quarter: From Centuries-Old Maghrebi Community to Western Wall Prayer Plaza). As a result, British Mandate forces conducted an investigation into the uprising and concluded that the al-Buraq Wall belonged to the al-Aqsa Mosque compound, thus reaffirming its status as a Muslim waqf, or endowment.14

Israel’s violations of the Status Quo

When Israel occupied East Jerusalem in June 1967, it recognized the Status Quo agreement regarding the Haram al-Sharif in order to avoid escalating tensions with regional countries. However, it quite literally seized control of everything around it:

- In June 1967, it razed the Moroccan Quarter of the Old City, located directly below the al-Aqsa Mosque compound, building the prayer plaza across from the Western Wall today in its place.

- Moreover, it confiscated the keys to the Dung Gate, located on the southern part of the Old City wall, with closest access to the Haram al-Sharif.

- Finally, it seized control of the al-Buraq Wall, as its predecessors had attempted to do in 1929.15

Importantly, the custodianship of the waqf of the al-Aqsa Mosque compound had come under the Hashemites (who would come to rule in Jordan) in 1924, and remains so to this day.16 Despite being at war between 1967 and 1994, Israel and Jordan maintained this arrangement as part of the Status Quo, and successive Israeli governments continued to limit Jewish access to the Haram al-Sharif to the Western Wall in order to avoid escalations. Nonetheless, tensions did emerge over the course of the last few decades, including in 1981 when Israel began building a tunnel under the mosque compound; Jordan responded by cementing it shut.17 Stories like these abound, but until September 2000, when Ariel Sharon entered the al-Aqsa grounds with a coterie of six Likud members and hundreds of Israeli security forces thus sparking the Second Intifada, Israel largely observed the Status Quo agreement.

Between 2001 and 2003, Israel upheld the ban on access to the Haram al-Sharif by non-Muslims. But in 2003, and without notifying Jordan, Israel restored access to non-Muslims, setting a dangerous precedent which has since led to a series of violent confrontations between Muslims and Israeli occupation forces in the al-Aqsa Mosque courtyards.18 Indeed, unauthorized incursions into the Haram al-Sharif by extremist Jewish politicians and settlers have continued unabated since the Second Intifada, with the most frequent and violent occurring in 2021 and 2022.

In January 2023, Jordan’s King Abdullah II hosted newly elected Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Amman to address the rising violence in Jerusalem, as well as increasing tensions between the two countries which were exacerbated by Israeli police banning the Jordanian ambassador to Israel from entering the Muslim holy site days prior.19 As an outcome of the meeting, Netanyahu agreed to commit to the Status Quo, disregarding the existing transgressions—essentially creating a new state of affairs.20

Indeed, the Second Intifada reconfigured access to the Haram al-Sharif in Israel’s favor. As Marjieh explains:

Today, Israeli occupation forces are stationed inside the holy site, and they completely control the entrance of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Although Muslims are allowed to enter from all gates, non-Muslims can only enter through al-Magharbeh Gate. Temple Mount groups and Israeli extremists enter from al-Magharbeh Gate as well, and the Waqf is prohibited from preventing them from entering the site. The Waqf can no longer prevent Israelis in military fatigues from entering, although this act is banned per the mosque’s regulations. Israeli occupation authorities have systematically limited Palestinians’ access to the compound, and even went as far as prohibiting Palestinian Muslims from entering their holy site while allowing exclusive access to Jews, in violation of the Status Quo, and of the right to freedom of worship, freedom of access, and freedom of expression.21

In this respect, Netanyahu’s promise to abide by the Status Quo rings hollow. Indeed, one day after his promise, Itamar Ben-Gvir, Israeli Minister of National Security and an extremist, vowed to continue storming the Muslim holy site despite Netanyahu’s promise to the king of Jordan. In a statement he released on Wednesday, January 25, Ben-Gvir said: “With all due respect to Jordan, I did this, and I will continue to go up to Temple Mount (Al-Aqsa Mosque) . . . The State of Israel is independent, and has no tutelage from any other country.”22

Notes

“Israeli Forces Attack Worshippers in al-Aqsa Mosque Raid,” Al Jazeera, April 5, 2023.

Dalia Hatuqa and Alia Chughtai, “Timeline: al-Aqsa Raise, Closures and Restrictions,” Al Jazeera, April 20, 2022.

It is important to note that Israel’s top religious officials have officially banned Jews from entering the Haram al-Sharif, what they call the Temple Mount, since 1921 because it is unknown where the temple’s most holy site is located and treading on it risks desecration.

Lubna Masarwa and Huthifa Fayyad, “Israeli Forces Storm al-Aqsa Mosque for Second Time in 48 Hours,” Middle East Eye, April 17, 2022.

Shira Rubin, “Right-Wing Israeli Minister Challenges Own Government with Visit to Temple Mount,” Washington Post, January 3, 2023.

Al Jazeera Staff, “Analysis: Israeli Government Starts by Pushing Far-Right Agenda,” Al Jazeera, January 17, 2023.

Arab News Staff, “Pope Francis Defends Preservation of Historical Status Quo in Jerusalem,” Arab News, January 10, 2023.

Mounir Marjieh, “Jerusalem’s Status Quo Agreement: History and Challenges to Its Viability,” Arab Center, June 7, 2022.

See Walter Zander, “Imperial Firman of February 1852, concerning the Christian Holy Places,” in Israel and the Holy Places of Christendom (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971), 178.

Zander, “Imperial Firman,” 9.

Daoud Kuttab, “Muslim Family Will Not Give Up Keys to Iconic Jerusalem Church despite Pressure,” Al-Monitor, November 6, 2018.

World Monuments Fund website, “Church of the Holy Sepulchre: Completed Project.”

World Monuments Fund website, “Church of the Holy Sepulchre: Completed Project.”

Marjieh, “Jerusalem’s Status Quo Agreement.”

Western Wall Commission, “Jerusalem—United Kingdom Commission Report on the Western Wall (1930),” United Nations, December 1930.

Marjieh, “Jerusalem’s Status Quo Agreement.”

The International Crisis Group (ICG) and Michael Dumper, “The Status Quo of the Status Quo at Jerusalem’s Holy Esplanade,” Jerusalem Quarterly 63/64 (2015): 120–41

ICG and Dumper, “The Status Quo of the Status Quo.”

Marjieh, “Jerusalem’s Status Quo Agreement.”

Motasem Dalloul, “Is Jordan Really the Custodian of Jerusalem’s Holy Sites?” Middle East Monitor, January 19, 2023.

Barak Ravid, “Netanyahu Meets Jordan’s King and Commits to Status Quo in Jerusalem,” Axios, January 24, 2023.

Marjieh, “Jerusalem’s Status Quo Agreement.”

Jordan News Staff, “Ben Gvir Vows to Storm al-Aqsa despite Netanyahu Pledge to Jordan,” Jordan News, January 25, 2023.