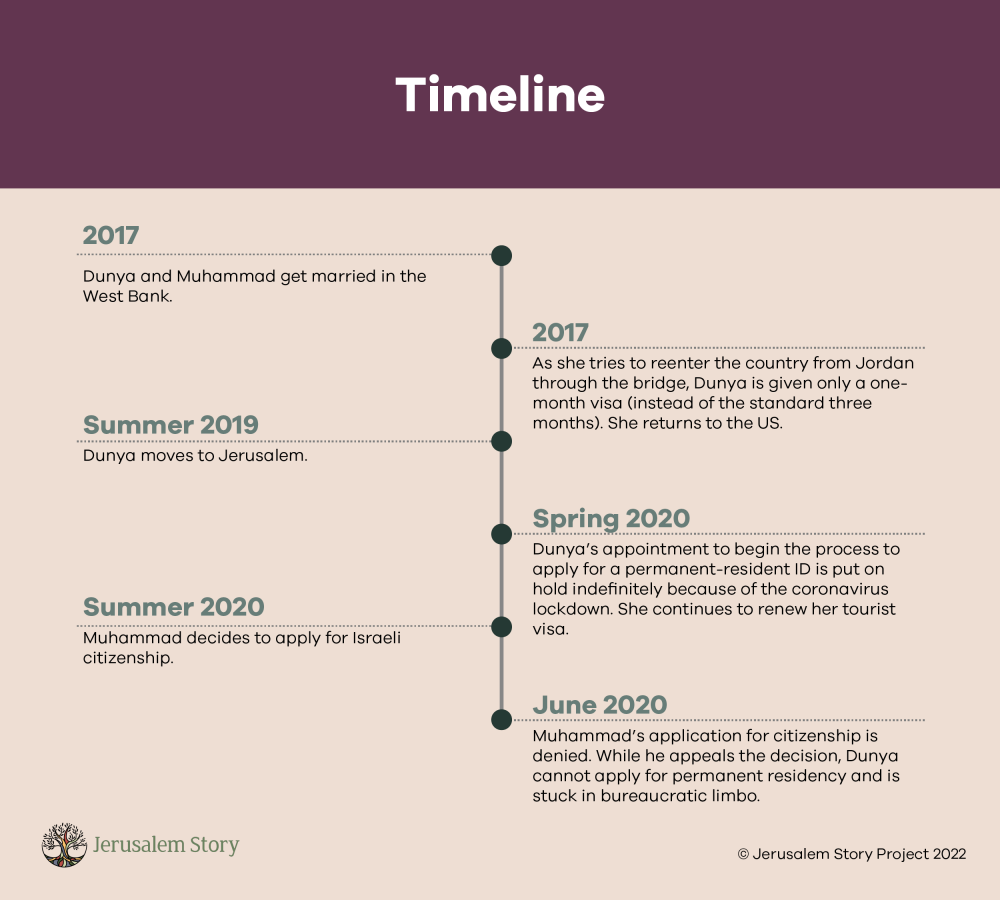

At that point, Muhammad decided to apply for Israeli citizenship. The manager at the Ministry of Interior advised the couple to wait until they receive a response about his citizenship application to resume their formal application for Dunya’s residency, because if Muhammad were to get citizenship, the process of obtaining residency for Dunya would be easier, and she could eventually be eligible for citizenship as well.

For a variety of personal reasons, including the prospect of engaging in yet another arduous and tiresome process, Muhammad did not apply for citizenship until 2020. This was a source of tension between Dunya and Muhammad, because she had asked him to apply for citizenship before she moved to Jerusalem. Dunya read online that if Muhammad was a citizen, it could make life easier for both of them.

In June, Muhammad’s application for Israeli citizenship was denied, because the Ministry of Interior claimed he did not prove that Jerusalem was his “center of life.” Muhammad is appealing the decision, but he does not know when he will receive a response. So for now, Dunya and Muhammad have to wait for one process to finish before starting another one.

Dunya explains that her marriage and professional life help her to maintain some equilibrium as she tries to establish a new life in a new country while she is at the mercy of a cumbersome and often mysterious process of applying for residency. Nationalistic reasons strengthen her resolve: “This is my homeland, and why shouldn’t I live here? Because that’s what [the Israelis] want at the end of the day—for us to leave. They’re trying to make it as difficult as possible for us for that reason. So at the end of the day, I will get my permanent residency. The question is, how long will it take?”