What it means to be a Palestine refugee has a long and complicated history dating to the 1948 Nakba, when an estimated 750,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes in Palestine, including nearly 75,000 who were displaced from Jerusalem and 40 rural villages around it.1 The question became more complicated following the displacement of about 300,000 more Palestinians during the 1967 Naksa, as well as more than 300,000 following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. This Short Take examines the international humanitarian and legal measures taken since 1948 to define, count, and provide support for the millions of Palestinians who are legally defined as “Palestine refugees” and who qualify for UNRWA assistance, as well as the dire challenges they face.

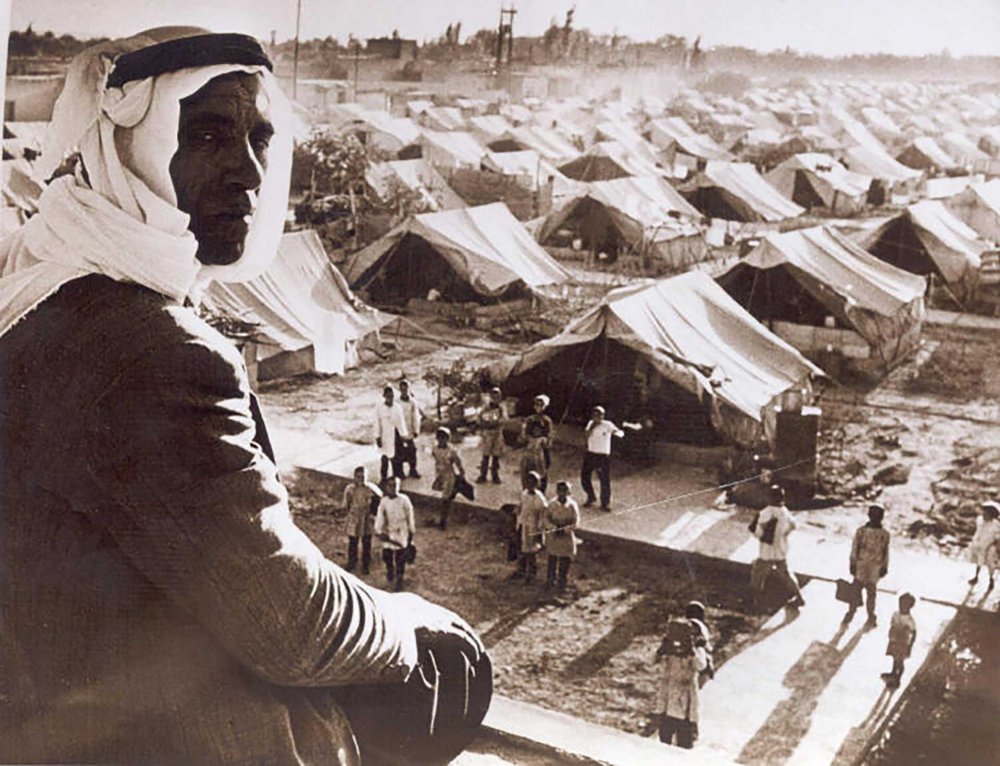

Credit:

© 1967 UNRWA Archive, photographer unknown

The Legal and Institutional Complexities of What It Means to Be a Palestine Refugee

Snapshot

The phrase “Palestinian refugees” is so commonplace as to be almost a cliché. But who actually qualifies for this status, and what does it mean?

Defining and Counting Palestine Refugees

Immediately after the Nakba, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the League of Red Cross Societies, and the American Friends Service Committee provided services for displaced Palestinians across the region. In December 1949, the UN General Assembly established the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to provide services for these Palestinians. The UNRWA subsequently established 58 refugee camps in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria as temporary “tented cities” to house the displaced Palestinians until they could return to their homes.2

By the UNRWA’s definition, Palestinians qualifying for registration with the UNRWA—and hence, eligible for services—are the citizens of Mandate Palestine and their qualifying descendants who were displaced from their homes in Palestine as a result of the Nakba and the Naksa. Specifically, Palestinian refugees are

[those] persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict. Palestine Refugees, and descendants of Palestine refugee males, including legally adopted children, are eligible to register for UNRWA services. The Agency accepts new applications from persons who wish to be registered as Palestine Refugees. Once they are registered with UNRWA, persons in this category are referred to as Registered Refugees or as Registered Palestine Refugees.3

Using records the aforementioned organizations compiled, the UNRWA began to conduct a census in 1950–51 to accurately determine the number of Palestinian refugees who would qualify for its services.

The census recorded approximately 875,000 Palestinian refugees scattered in refugee camps in neighboring countries at that time.4 But the 1967 War resulted in the displacement of about 300,000 more Palestinians. Although the UNRWA’s initial definition of Palestinian refugees did not apply to those Palestinians displaced in 1967, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly has been encouraging the UNRWA to “provide humanitarian assistance on an emergency basis” to those Palestinians.5

Therefore, the UNRWA established another 10 refugee camps for this new wave of Palestinian refugees.6 According to the UNRWA website, “Since then, UNRWA has been updating files from voluntarily supplied documentation on the original refugees and their descendants through the male line,” and today, it has registered 5.9 million Palestinian refugees who are eligible for its services in 68 refugee camps in the region.7 The UNRWA has also identified an additional 685,000 “persons of concern”8 who have not registered with it but are eligible for its services according to its Consolidated Eligibility and Registration Instructions (CERI), created in 2009 to ease the UNRWA’s operations.9

The global relevance of the Palestine refugee crisis

Palestinians are not the only refugees in the world, but their plight set a precedent for the UN to legislate laws protecting refugees everywhere. The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol define the term “refugee” and determine the international standards for affording refugees protections and services through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), established in 1950 to address the refugee crisis that resulted from World War II. While the 1951 Refugee Convention outlined the UNHCR’s scope and responsibilities, Palestinian refugees were excluded from its mandate since they fell under the UNRWA’s. Nonetheless, “definitions of refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention and of Palestine refugees per the UN General Assembly are complementary.”10

Indeed, Article I A (2) of the 1951 Refugee Convention applies in theory to Palestinians, as well. The convention determined that

the term “refugee” shall apply to any person who:

… As a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.11

Article 1 D of the convention defines those who are ineligible for protection under the UNHCR: “This Convention shall not apply to persons who are at present receiving from organs or agencies of the United Nations other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees protection or assistance.” This included Palestinians receiving assistance from the UNRWA. However, it makes a provision for the event that other UN agencies cease to operate:

When such protection or assistance has ceased for any reason, without the position of such persons being definitively settled in accordance with the relevant resolutions adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, these persons shall ipso facto be entitled to the benefits of this Convention.12

Accordingly, should the UNRWA cease its services, Palestinian refugees would come under the mandate of the UNHCR.

The Unending Crises of the UNRWA’s Palestine Refugees

In 1992, and with the displacement of more than 300,000 Palestinians from Kuwait upon Iraq’s invasion of the country, the UNRWA restarted its voluntary registration process for Palestinians wishing to receive its services.13 In other words:

Palestine refugees who were not registered in the early fifties can now apply for registration, provided that they approach any UNRWA registration office in person and are able to produce valid documentation proving their 1948 refugee status. Since 2006, husbands and descendants of registered refugee women, known as “married to non-refugee” (MNR) family members, have also become eligible to be registered to receive UNRWA services.14

In 1996, the UNRWA digitized its registration process, and in 2010, it created an online system, the Refugee Registration Information System (RRIS), to store and manage the millions of files in its records. Palestinians who are registered in the system can access their records upon request through a secure online portal containing “documents pertaining to their family history over the last 70 years.”15

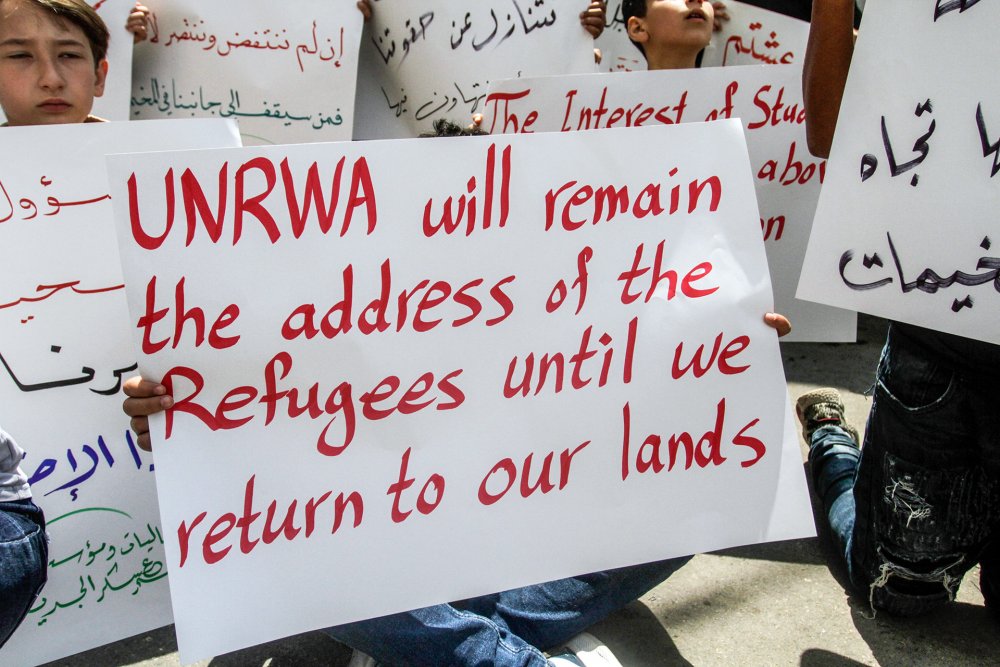

On November 18, 2019, the UN General Assembly convened a special committee to affirm the critical role that the UNRWA continues to play in providing assistance to Palestinian refugees.16

Specifically, the draft resolution, titled “Assistance to Palestine Refugees,” stated that the committee acknowledges

the essential role that the Agency has played for over 65 years since its establishment in ameliorating the plight of the Palestine refugees through the provision of education, health, relief and social services and ongoing work in the areas of camp infrastructure, microfinance, protection and emergency assistance.17

In the next draft resolution, titled “Persons Displaced as a Result of the June 1967 and Subsequent Hostilities,” the General Assembly reaffirmed the rights of Palestinians displaced during 1967 “to return to their homes or former places of residence in the territories occupied by Israel since 1967,” stressing the necessity of accelerating this process. “In the meantime,” it noted, the resolution

Endorses … the efforts of [the UNRWA] to continue to provide humanitarian assistance, as far as practicable, on an emergency basis, and as a temporary measure, to persons in the area who are currently displaced and in serious need of continued assistance as a result of the June 1967 and subsequent hostilities.18

The UNRWA Itself Faces a Crisis

But for a decade, the UNRWA has been suffering from shortages in aid due to a range of political, economic, and natural factors, including global austerity measures, instability in countries like Syria and Lebanon, and devastating regional earthquakes. Contributing to the crisis, former US president Donald Trump eliminated US contributions to the organization in 2018;19 the United Arab Emirates followed suit, slashing funds to the organization from $51.8 million in 2018 to $1 million in 2020. A November 2018 UN resolution “strongly appeal[ed] to all Governments and to organizations and individuals to contribute generously” to remedy the UNRWA’s “structural underfunding” in a 10-page resolution, “Operations of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” the longest draft resolution that emerged from the November meeting.20

Despite the resumption of US contributions by President Biden in 2021, the UNRWA has been struggling to provide basic services to the growing number of Palestinian refugees, especially in Lebanon, where the economy has been in freefall and where violence in and around Palestinian refugee camps is rampant.21 Beyond Lebanon, the UNRWA needs about $1 billion annually to manage and provide services to the 5.9 million Palestinian refugees in the region.

On June 2, 2023, the UN held a conference in New York to garner pledges for the UNRWA. Member states in attendance expressed their commitment to supporting the organization and pledged $828.3 million, “of which US$13.2 were fresh contributions.” Nonetheless, Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini lamented, “While we are grateful for the pledges announced, they are below the funds that the Agency needs to keep over 700 UNRWA schools and 140 clinics open from September onwards.”22

In a separate appeal published the same month, the UNRWA clearly laid out its budgetary needs in several diagrams in order to show the “critical financial shortage” expected to start in September 2023. Specifically, it urgently appealed for:

- US$75 million to secure food assistance to nearly 1.2 million people in the Gaza Strip (with US$35 million needed by August)

- Funding for cash assistance (US$30 million) in the fourth quarter for more than 600,000 Palestine Refugees in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon

- Nearly US$15 million in Lebanon for hospitalization and support to 5,000 cancer patients amid a healthcare collapse in that country

- An additional US$9.8 million for the response to the earthquake in Syria, to help repair Palestine refugee homes and other emergency response

- Nearly US$7 million in the occupied West Bank, amid unprecedented levels of violence, for cash assistance, emergency health, education, and environmental health.

- Some US$12 million in Jordan to maintain cash assistance for Palestine Refugees displaced from Syria.

Given the dire conditions of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), and Gaza—in addition to the worsening global and regional economic, political, and environmental climate—UNRWA representatives remain wary of the organization’s future and its ability to provide services for the largest number of refugees it has ever served.

Notes

See The West Side Story.

“Profile: Far’a Camp,” UNRWA, accessed August 30, 2023.

“Consolidated Eligibility and Registration Instructions (CERI),” UNRWA, May 24, 2006.

“What We Do,” UNRWA, accessed August 30, 2023.

“Annual Operational Report 2019,” UNRWA, 2020, 169.

“What We Do.”

“What We Do.”

“Global Issues: Refugees,” United Nations, accessed August 30, 2023.

“Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees,” UNHCR, December 2010, 4, 14.

“Convention and Protocol,” 16.

Toufic Haddad, “Palestinian Forced Displacement from Kuwait: The Overdue Accounting,” Al-Majdal Magazine, no. 44, 2010.

“What We Do.”

“What We Do.”

“United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East: Report of the Special Political and Decolonization Committee (Fourth Committee),” United Nations General Assembly, November 18, 2019.

“Report,” 7.

“Report,” 7 (emphasis in original).

Karen DeYoung, Ruth Eglash, and Hazem Balousha, “U.S. Ends Aid to United Nations Agency Supporting Palestinian Refugees,” Washington Post, August 13, 2018.

“Report,” 9.

“What’s Behind the Fighting in Ein el-Hilweh Palestinian Refugee Camp?” Al Jazeera, July 31, 2023; Dalia Hatuqa, “UNRWA Limps Forward after Years of Trump Administration Pressure,” Al Jazeera, February 10, 2021.