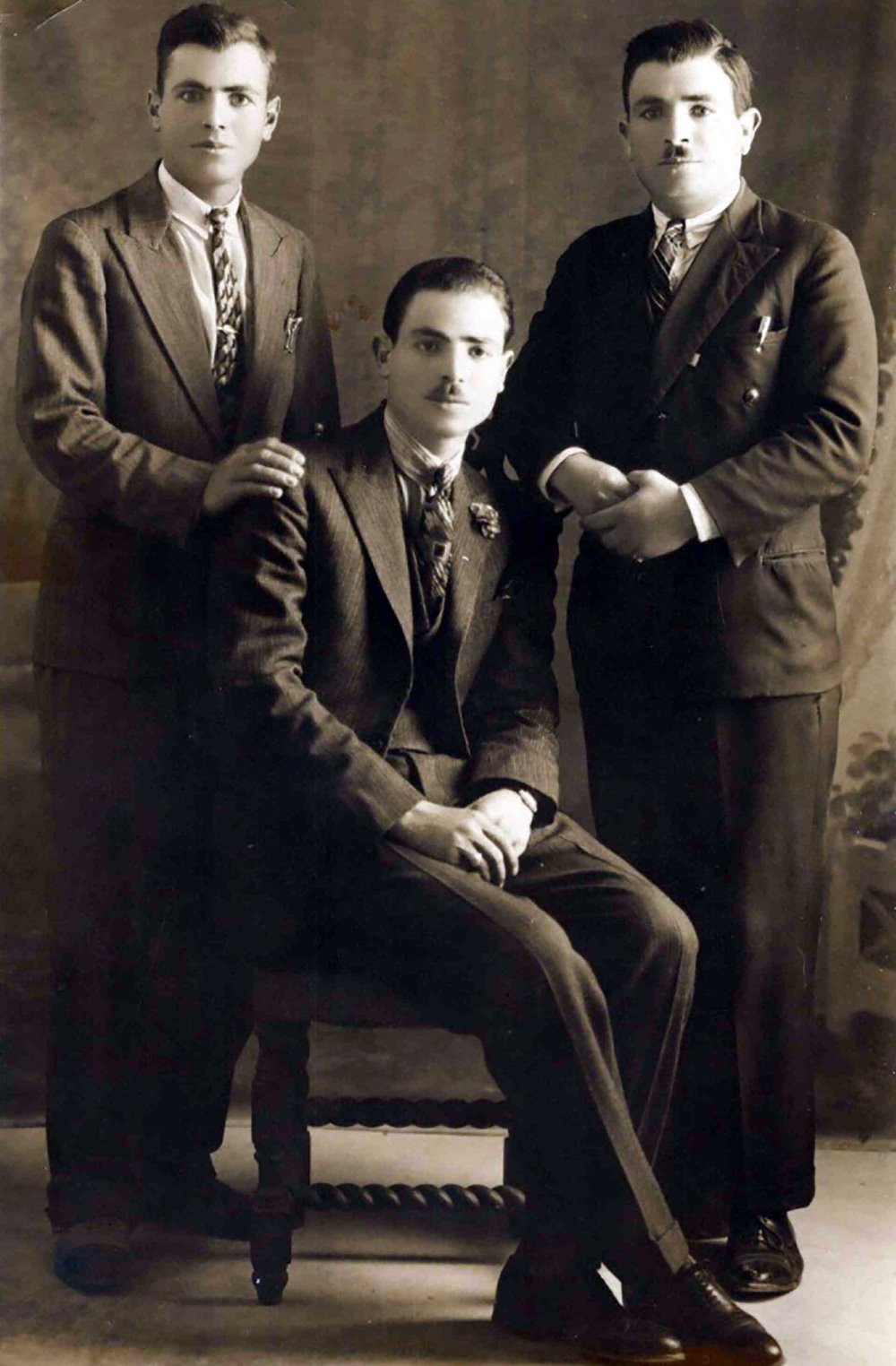

Salon Hammoudi: Jerusalem’s Hair Stylist for Women in the 1930s

Credit:

Courtesy of Mohammad Hammoudi

The Hammoudi Family and the Loss of a Jerusalem Home: One Family’s Multigenerational Longing

Snapshot

A Jerusalemite family, exiled in 1948, remains deeply attached to the city where the unique home their grandfather lovingly built still stands in Qatamon in what is today West Jerusalem.

The Hammoudi siblings Muzayan, Mohammad, and Mirna met with Jerusalem Story in Amman, Jordan, in July 2023 and shared their family story.

“I was born and raised in Amman, but essentially, I am a Jerusalemite,”1 Mohammad states matter-of-factly. Mohammad is an electronics engineer who worked most of his life in information and communications technology (ICT) with major high-tech companies, including IBM, Microsoft, and Cisco. He is now a successful business owner providing ICT consulting and services, mostly in the Gulf. “My father was born in Jerusalem,” he asserts. “My grandparents from both sides of the family were born in Jerusalem. My entire lineage can be traced to Jerusalem.”

Mohammad explains that his paternal grandfather (also named Mohammad) had “Jerusalem’s only women’s hair salon in the 1930s; he was a coiffeur,” a hair stylist.

The use of descriptions in French and English may well be indicative of the Palestinian Jerusalemite generation of the 1930s and its openness to Western culture notwithstanding the colonial implications of such openness: “Unlike today, Jerusalem had been open prior to 1948. We knew that our grandfather had close Muslim, Christian, and Jewish friends. Our own parents had a mixed marriage in 1962, and my grandfather had no issues whatsoever with it. He believed we were all equally the children of God.”

Mohammad Senior lived in one of Jerusalem’s nicest neighborhoods, al-Baq‘a, with his parents and five siblings. Upon getting married and starting a family of his own, he achieved his dream of building a house in the nearby New City neighborhood of Qatamon, outside the Old City walls, in the 1930s. He had worked hard to make this happen: He was a skilled hair stylist and had developed a loyal clientele.

Salon Hammoudi was close to Ma’man Allah Cemetery. “To this day, we hear stories about how well the salon was doing in the 1930s. In fact, my siblings and I found out that our grandmother (Muzayan) often got jealous from the many regular and beautiful customers who raved about our grandfather’s salon,” Mohammad shares. “From what we gathered, the salon was close to Ma’man Allah Cemetery, probably close to the Paris Square, but there are no traces of the salon today. It’s completely gone.”

The three Hammoudi siblings, now adults, pondered some of the stories gathered about their late grandfather’s famous salon in Jerusalem: They imagined the place being full of life with women getting beautiful hairdos while sharing daily news and gossip. Prior to 1948, they observed, no one bothered about their neighbors’ religion—“they were like family to one another.” It is a claim frequently found in memoirs written by Palestinian Jerusalemites about relations during the British Colonial Mandate period.

Sweeping Floors at a Beirut Cinema

The Nakba of 1948 changed Jerusalem’s pluralistic identity and transformed his grandfather’s entire life trajectory. Mohammad recalls:

After building a house in Qatamon in the 1930s and making a name for himself as a professional women’s hairdresser, my grandfather—like many other Palestinians—became displaced overnight. He lost the house, the salon, and all sense of stability. He and his family ended up in Lebanon for what they assumed would be a couple of weeks. They would become stranded there for two years as refugees.

The siblings explained how their grandfather, a celebrated hairdresser in Jerusalem, had to settle for sweeping the floors of a Beirut cinema when he became a refugee. It was excruciatingly hard to get by as Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, they noted. Their paternal grandmother, Muzayan, is said to have frequently heated water in a large pot (at the refugee camp) to give the impression that she was cooking or making soup (to create a cozy feeling of home where there was none).

Two years later, they managed to relocate to Ramallah; they moved to a small house, and Mohammad Senior opened a hair salon with the same name as his Jerusalem shop, Salon Hammoudi. He would spend the rest of his life in Ramallah. “He would rarely go to Jerusalem,” the grandson noted, as he could not bear the reminders of what he had lost: “The house he had built was seized by the Israelis, even though he had the deed.” He passed away in 1987.

The House That Was

“The family did not speak much—if at all—about the painful subject of losing their home and life in Jerusalem: They buried the pain,” Mohammad reflected. Like many others who have endured collective trauma, “my grandfather never talked about it,” he noted. Mohammad’s father, Ghaleb, was 13 years old when the family left Jerusalem.

In 2023, Mohammad (the grandson) decided to examine his father’s files. He and his wife, Hanya, found a complete set of documents, including building licenses of the houses in al-Baq‘a and Qatamon. He had been wanting to introduce his three daughters to their family roots in Jerusalem: for them to see the house his grandfather built, and that his father grew up in. Finding the documents crystallized his determination to do so.

“It was a quest that I started almost 30 years ago,” Mohammad shares:

It was very important for me to show my daughters our roots, and for them to realize that they are true Jerusalemites . . . That they are from—and belong to—the holiest place on earth. I also felt very proud to be able to show them what my grandfather had created 100 years ago. The house, with the musical notes, stands testimony to the Palestinian cultural history and civilization. I also wanted to establish our right to that house. I ventured on this journey for my grandfather, my father, my aunts, and more importantly my daughters; to ensure that they continue the fight and preserve the dream.

In the summer of 2023, the family organized a visit with Tarek Bakri, a Palestinian researcher based in Jerusalem who documents personal stories and the displaced Palestinian villages of 1948 through visual documentation. Nahil Aweidah, who had also lost her family homes in West Jerusalem and now lives in Amman, was a great help for the family; she easily remembered and could describe where the Hammoudi family home was located. “Her memory was so sharp: she would explain the roads better than Google Maps,” Mohammad observed.

Walking to the entrance of the house, the family was enchanted by the iron driveway gate and the metalwork of the house. Mohammad recalled that his grandfather loved music and played the oud. He had incorporated his love of music into the house he built: While Palestinian homes typically have decorative metal grills on the windows, the Hammoudi home is unusual in that the metal grills include decorative musical notations that he must have had specially made for his house. “He was a rather artistic person, and there are traces of this to this day in Jerusalem: The house itself may not be particularly impressive; it’s nothing like the Bisharat villa or the rich Palestinian homes in the Qatamon area,” Mohammad explained. “It’s a rather simple house. What makes the house special is the row of music notes on the metal gate—that’s what makes it unique.”

Emotional Encounters

Upon seeing her great-grandfather’s house in the heart of Jerusalem, Mohammad recalls, his eldest daughter, Nadine, 31, said that this experience was “the most surreal feeling” she ever experienced. “She said: ‘It was the softest yet hardest awakening.’” Being a fourth-generation daughter of the Palestinian diaspora, standing at the curb of their home instilled in her a deeper and more genuine sense of belonging to Jerusalem. “‘It made me hold on to our land even stronger, wanting to return, and we will,’” Mohammad recalled Nadine telling him at the time.

Upon seeing the house, the second daughter, Yasmine, 28, found herself imagining what her great-grandfather might have felt as he designed and built his family home, and how the first night of residing in his creatively designed home must have felt like for him, his wife, and children. Mohammad recalled her words:

I imagined my grandfather, my sido, playing around the house as a young and innocent child, not knowing what lies ahead. I imagined the terror sneaking up on them as they started to hear about more and more Palestinian families being targeted, killed, and having to flee their homes. And last, I imagined the day it would be their turn . . . what it was like for them to pack up whatever they could, take one last look at their house—their home that held unimaginably beautiful memories—and leave. I imagined that maybe, if things had been different, I would have unimaginably beautiful memories of my own in this unimaginably beautiful house. Yet somehow, it still felt like I came back home.

The third daughter, Mona, 21, said that she never knew “the feeling of being robbed until we stood in front of our home in Qatamon, al-Quds.”2 Besides the physical presence of the house itself, “the feeling,” she shared, “was more than that. It was the theft of the life that could have been for us. I remember looking at our home, imagining how different life would have looked for myself, my father, my grandfather, and my great-grandfather. Birthdays would have been celebrated here. Meals would have been shared here. Life would simply have been here.” She shared how all of these meaningful details played out in her head about the home that stood in front of her: “The most painful feeling is knowing that my life, my memories, as well as those of the generations before me, all should have been here.”

Although this would be his daughters’ first trip to the house, Hammoudi himself had seen the family house once before. In 1987, when his grandfather passed away in Ramallah, he, his father, uncle, and a taxi driver took a trip to Jerusalem to see their house in Qatamon. Mohammad sighed, “I can never forget how my dad cried by the house.”

A Buried Pain

Mohammad’s father, Ghaleb, managed to create a successful life for himself: He was passionate about fixing radios and got the chance to pursue his education in the UK and eventually became a pilot. “He became the first captain to work with Jet Airlines at the International Qalandiya Airport,” Mohammad explained, “where he would fly to Cairo and Beirut through a transit hub: They would temporarily close the roads for the planes to take off and land.” Today, the airport no longer exists; instead, a horrific military checkpoint at Qalandiya makes it difficult for pedestrians and cars to cross to the other side; they must first stop, get checked, and undergo surveillance.

Ghaleb, his wife, and three children lived in Amman while he worked as an airline pilot, and they visited Ramallah almost every weekend until June 1967. “Unlike these days,” Mohammad explains, “It was an easy drive that took them about 1 hour and 20 minutes door to door.”

The Life That Was

Talking to the three Hammoudi siblings who live in Amman today, there is a sense of utter injustice and sadness about the life of their grandfather—now buried in Jerusalem. However, it’s also clear that they have preserved their late grandfather’s openness and tolerance. “For us, religion is not an issue,” Mohammad stressed. “My parents actually had a mixed marriage in 1962 after they had met on a flight; my mother being Egyptian Christian, with Greek and French roots, and my father being Muslim.

“Our grandfather told us they had so many Jewish friends . . . They didn’t differentiate . . . They all lived together,” Mohammad recalled. Today, Israeli policies make easy commingling of communities impossible.

In Amman, the siblings maintain fond memories of their grandfather. “He passed away on the same day I graduated,”3 Mirna teared up.

“I think it’s important to tell the story,” Mohammad reflected. “Not just about the house, but about the spirit of Jerusalem . . . The life that was.”

He recalled the trees in the neighborhoods whose residents were forced out: “If only the trees could speak . . . They are the greatest witness to what had happened. My father died with a sense of melancholy. He did very well as an airplane pilot, but he carried a sadness about him. My grandfather, too, never spoke of the pain of losing his family home, the house he built, and his once-impressive salon. They rarely spoke about it—but the entire family seemed to have a lump in their throats whenever they remembered their house with the distinctive musical notes.”

Today, the house is inhabited by a Jewish man with Iraqi roots—a man, who before the Nakba, may easily have been a friendly neighbor sharing the open and tolerant space that Jerusalem provided in those days.

The Hammoudi home still stands in Qatamon, West Jerusalem, as shown here on January 19, 2024.

Credit:

Arda Aghazarian for Jerusalem Story

Notes

Mohammad Hammoudi, interview by the author, July 2023. All subsequent quotes from Mohammad are from this interview.

Mona Hammoudi, interview by the author, July 2023. All subsequent quotes from Mona are from this interview.

Mirna Hammoudi, interview by the author, July 2023. All subsequent quotes from Mirna are from this interview.