Shortly after this accusation surfaced, the assault claim was dropped, because the police admitted that Mustafa was telling the truth.4

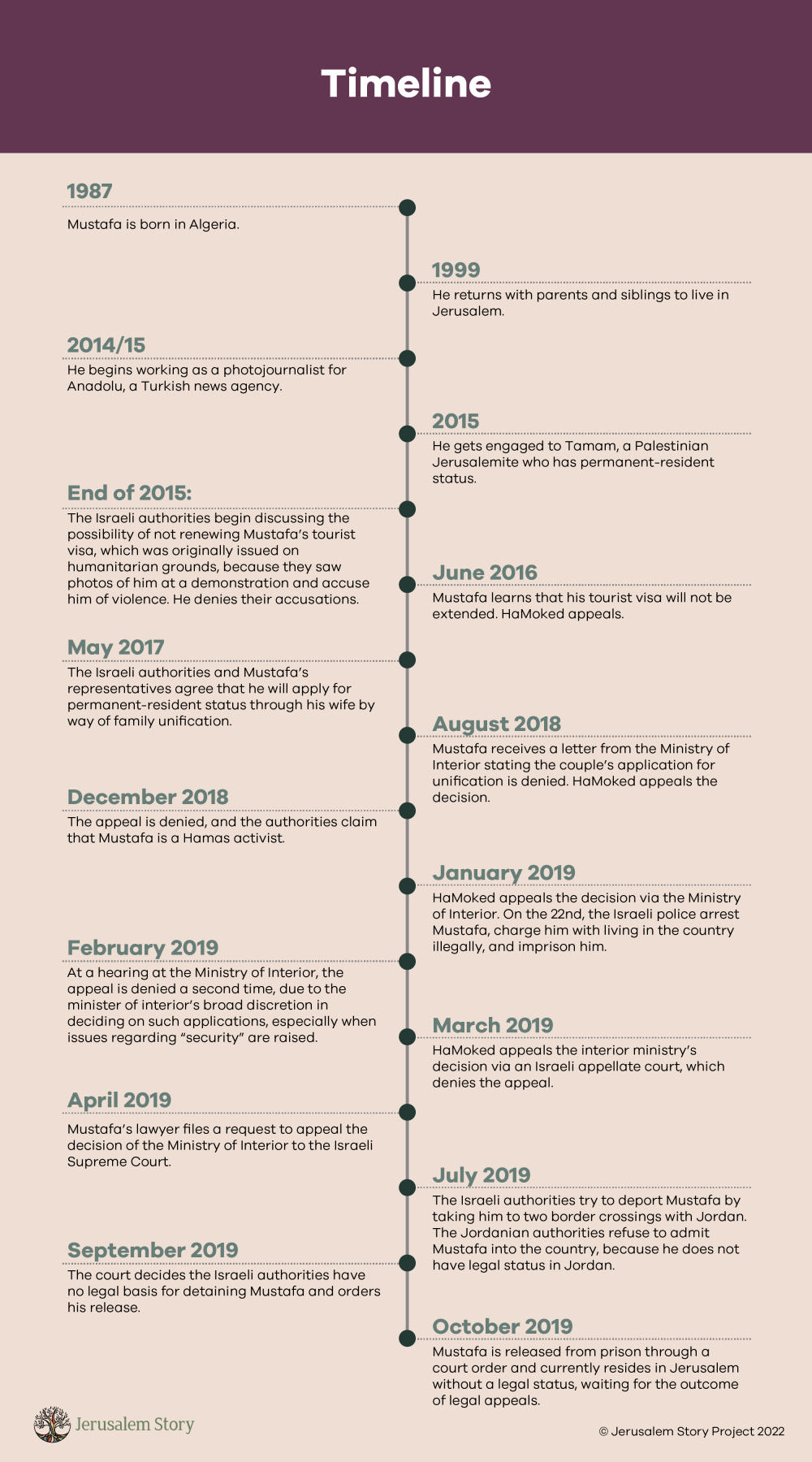

However, in June 2016, Mustafa learned that his visa would not be renewed. At this point, the Israeli human rights organization HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual became involved in the case and appealed the decision with a Ministry of Interior committee.

HaMoked lawyers explained in the appeal that Mustafa worked as a photojournalist and that as part of his job, he photographed demonstrations. At a hearing in May 2017, Mustafa’s lawyers and the committee agreed that he would apply for residency through family unification. (He was by then married to Tamam.)

Despite this agreement, Mustafa received a letter from the Ministry of Interior on August 28, 2018, stating that his application had been denied; no reason was given.5 HaMoked appealed the decision with the Ministry of Interior in December 2018 and learned that the ministry was claiming that Mustafa was a Hamas activist, which he categorically denied.

By the beginning of 2019 and after 20 years in Jerusalem, Mustafa’s residency status was more precarious than ever, with the threat of deportation looming over his head.6 But by then, his case directly impacted two other people, his wife and toddler, and their lives were also tied intimately to Jerusalem.

In January, HaMoked initiated yet another appeal with the Ministry of Interior’s visa tribunal on Mustafa’s behalf. The Israeli authorities responded by going to Mustafa’s home in the Wadi al-Joz neighborhood of East Jerusalem on January 22, 2019, and arresting him for living “illegally” in the country. They demanded he bring his Jordanian travel document.7

Tamam al-Kharouf later told Haaretz that one of the arresting officers told her to pack a big suitcase for Mustafa, because he was going away for a long time. When she tried to talk the police officers out of arresting her husband, they threatened to arrest her, too.8

She commented on the impact that her husband’s arrest had had on their family: