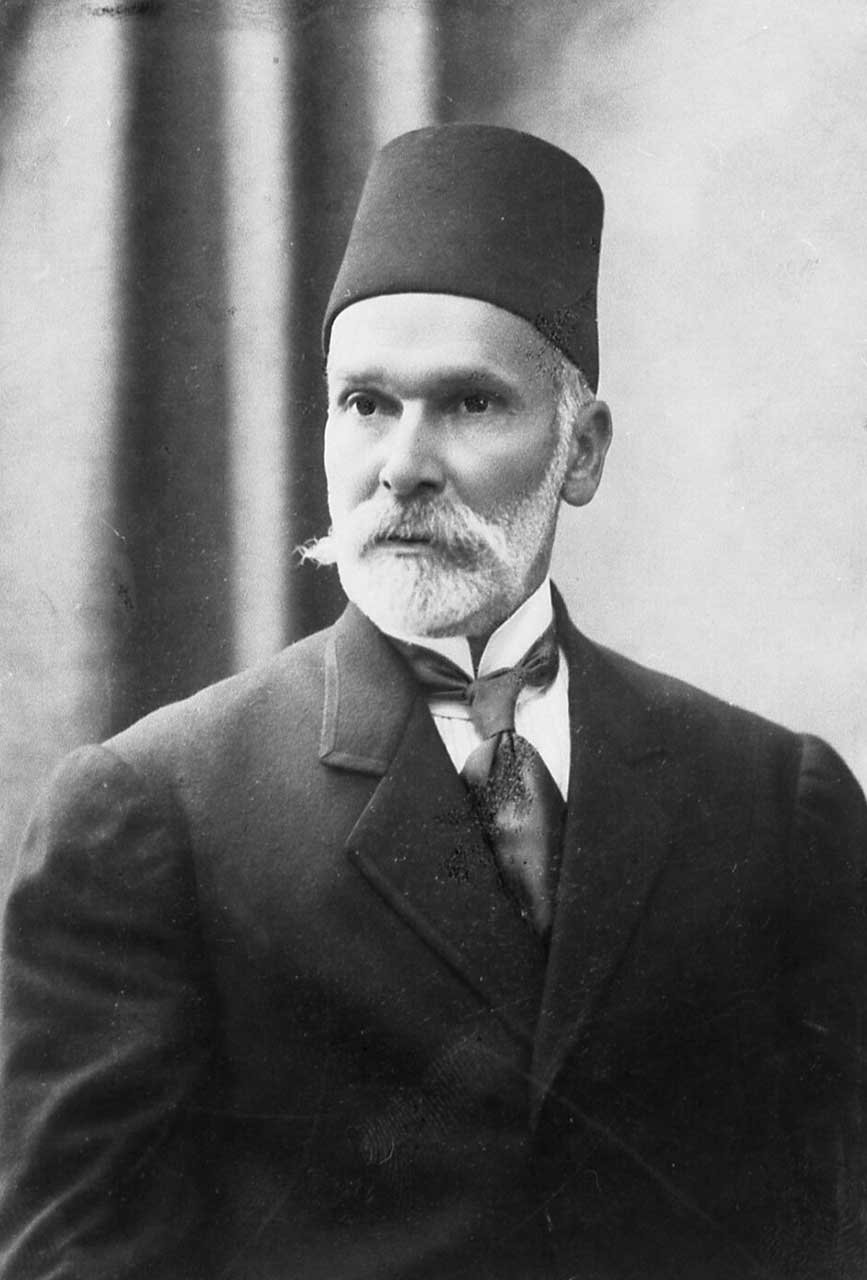

This photo album explores the history and spiritual life of the Armenian community in Jerusalem between the years 1898 and 1941.

Armenia became the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as the state religion in the early fourth century, and Armenian pilgrims flocked to Jerusalem for its religious significance; some permanently settled there. Jerusalemite Armenians are thought to form the oldest-surviving Armenian community in the diaspora.

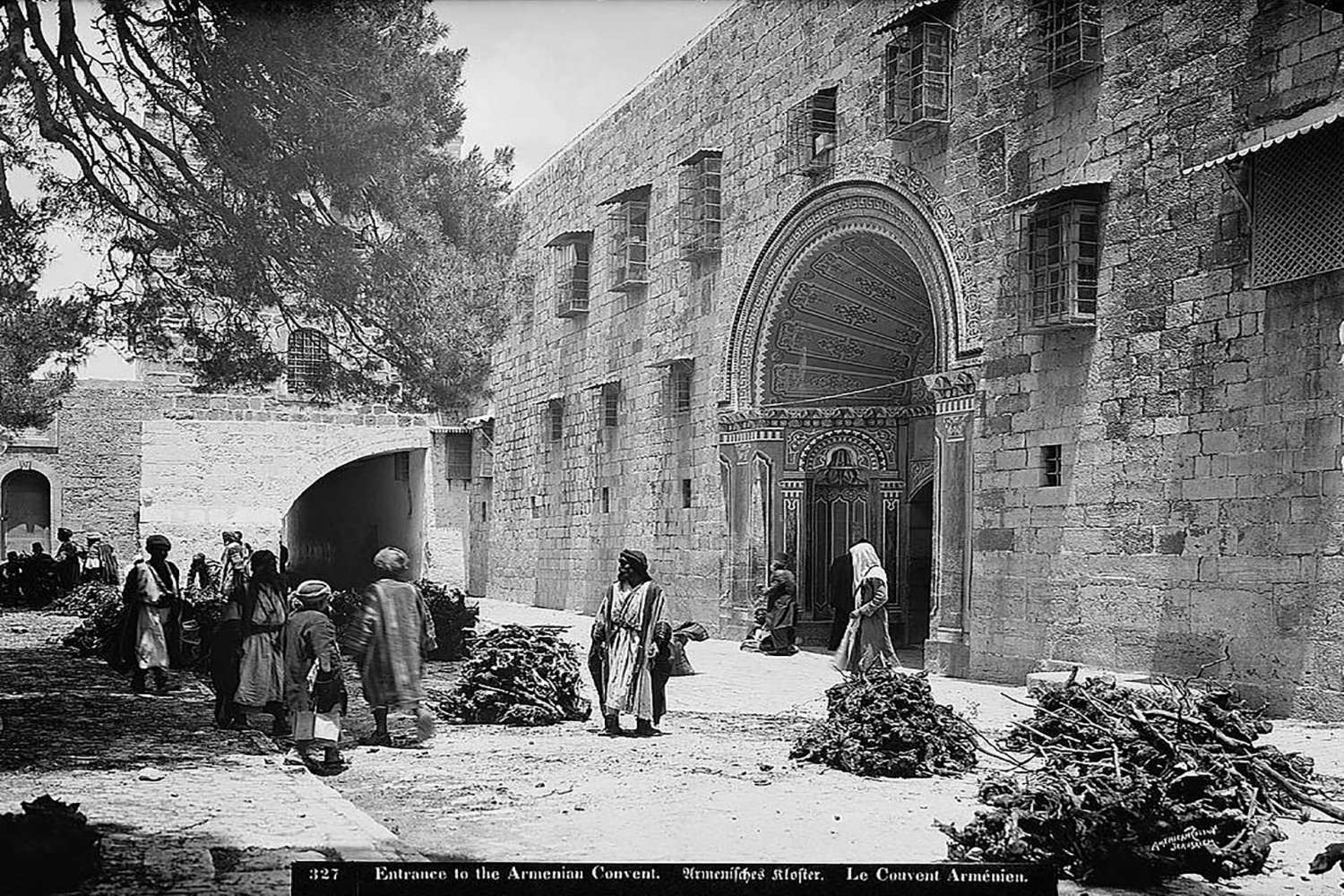

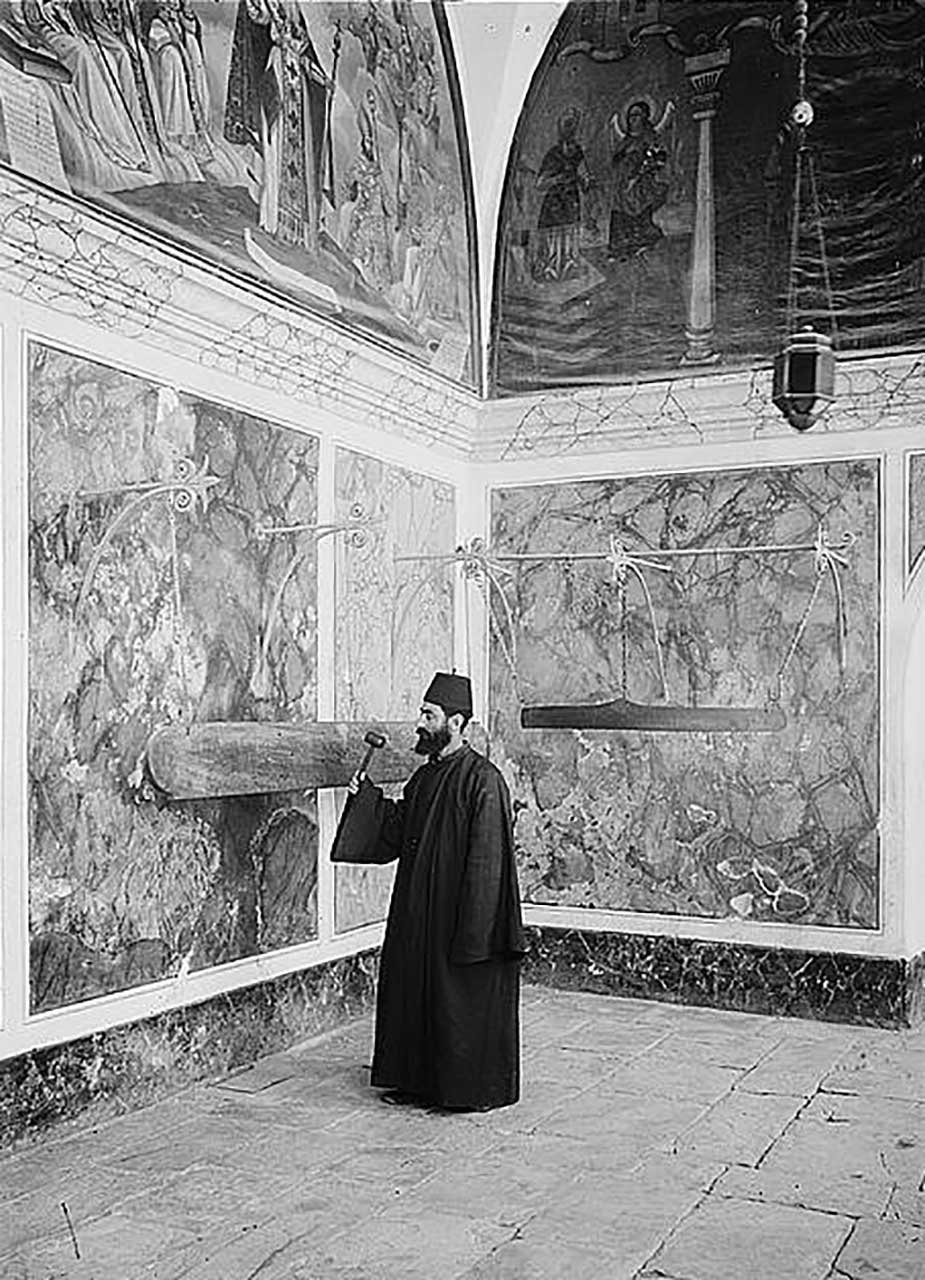

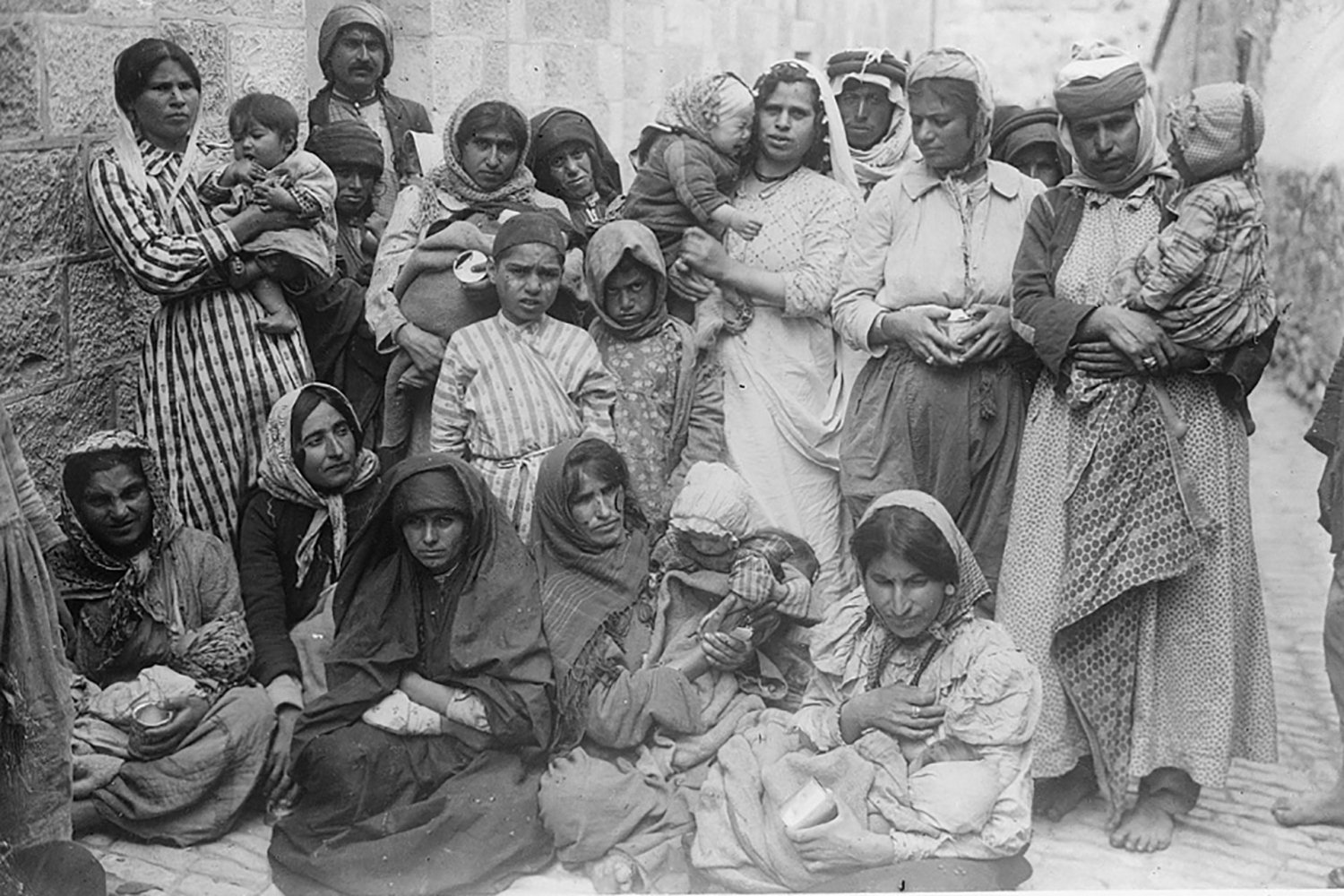

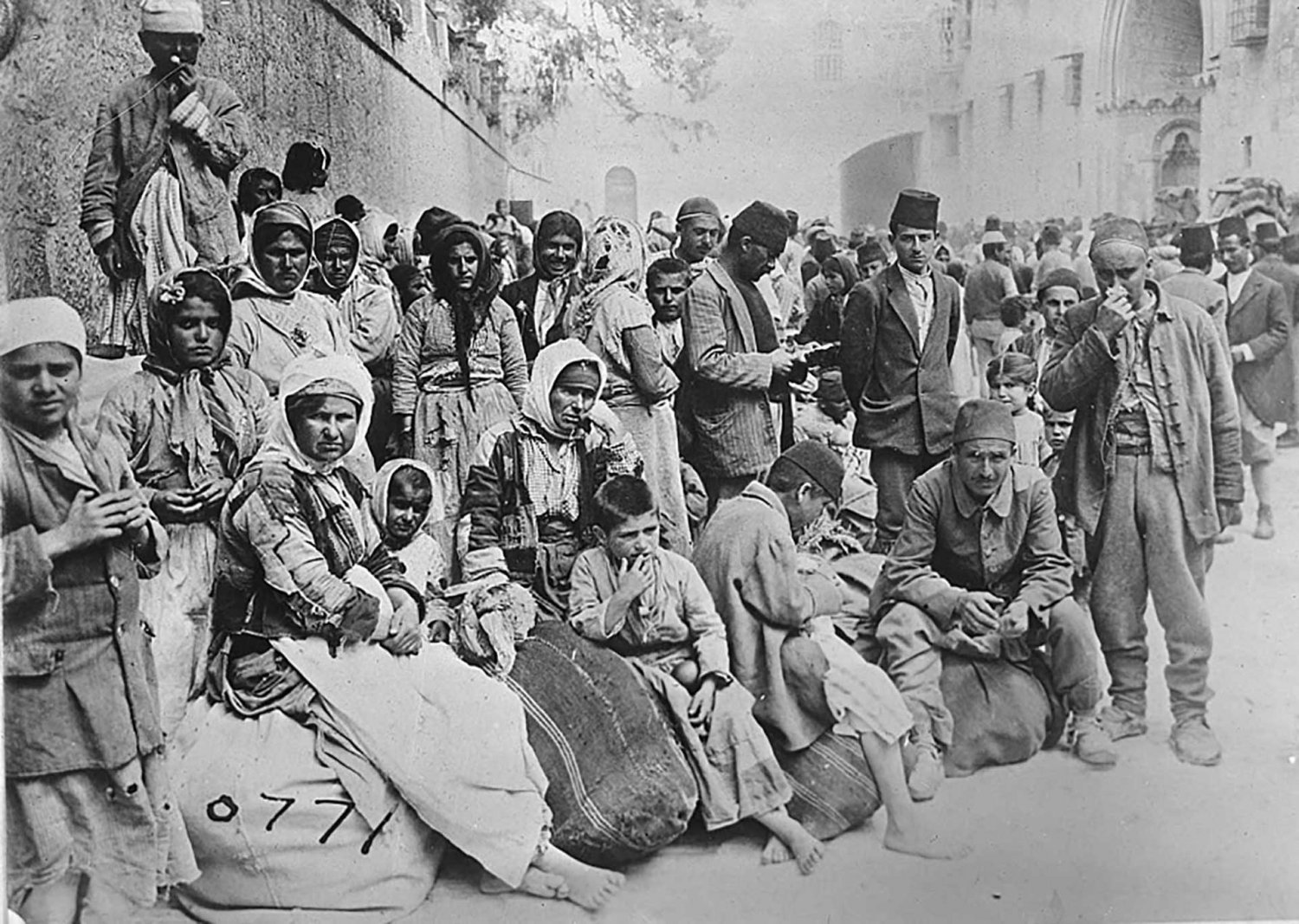

By the 13th century, Armenian churches were built, including the St. James Monastery, which was built on the remains of a fifth-century church, on a site that was identified as the burial place of the first bishop of Jerusalem (St. James Minor), and around which an Armenian quarter slowly developed. The monastery served as a refuge for the Armenian poor; a hospice was later attached to the monastery, further solidifying the community’s relationship with their church. A secular Armenian community of merchants and artisans also settled in the city and contributed to its cultural legacy by establishing and leading several crafts such as manuscript production, ceramic arts, and photography. According to an Ottoman census, between 2,000 and 3,000 Armenians lived in Palestine prior to World War I; most of them were in Jerusalem.1 However, their numbers dramatically increased beginning in 1915, as genocide survivors from other parts of the Ottoman Empire sought refuge in Palestine and Jerusalem, mainly in the Armenian Quarter of the Old City. The refugees formed a “second wave” of the community.

The Armenian community has long been an integral part of the historical, social, and cultural fabric of the Old City of Jerusalem.

This photo album offers a glimpse into the lives of Armenian Jerusalemites at the turn of the century, with the Armenian Church of St. James serving as a focal center and refuge from war as a backstory. In this album, we see devout members of the St. James congregation performing religious rituals and celebrating holy occasions; we see Armenian refugees upon their arrival to Jerusalem as well as skilled artisans at work.