Aida Najjar (b. 1938 in Jerusalem) was a writer and researcher who did development work in several parts of the world and wrote about the Palestinian press and life in Jerusalem before the Nakba.

Early Childhood in Lifta

Najjar was born on December 12, 1938, in Lifta, a village on the western outskirts of Jerusalem. At that time, it was one of the largest Palestinian villages in the area. She had a joyful childhood with her brother Aref and six sisters: Arefa, Nahida, Rifqa, Samira, Nawal, and Na’ela. Her brother later studied at the American University of Beirut and went on to become Lifta’s first engineer. Her father, Ali Ismail, a contractor and the village mukhtar, and her mother, Fattoum, were both hard-working individuals.

Najjar described her childhood home in Lifta in various interviews and publications. She noted that it was made of the modern-style white sesame jasper stones, surrounded by water streams and trees, and birds chirping from all directions:

The house, encircled by a wrap-around balcony, offered panoramic views of the captivating nature. Close to the house was Schneller’s farm [in Upper Lifta] where children—siblings and neighbors; boys and girls—found a home and playing field. To this day, the sight of the red roses adorning that staircase denote[s] the meaning of a happy home.1

Najjar was not quite 10 years old when she and her family were displaced during the Nakba. They first went to al-Tur in Jerusalem but then had to leave again when it became unsafe. They then headed for Zarqa in Jordan and lived there for a while before settling in Amman. More than 60 years later, she expressed strong feelings for her childhood home: “It is the place that marks one’s identity and personality.”2

Najjar not only loved her home and village but also loved the city of Jerusalem. In her interview with the Israeli nonprofit Zochrot from 2013, she expressed her sense of grief about losing their place. Among the things she described from her childhood were the white flowers that she and other girls from Lifta used to collect on their way to school and give to the teachers:

I remember that we preferred to walk to school so we could look at the trees and the souk. Before the war we were living in peace, dreaming of the best possible future.3

Education

In Jerusalem, Najjar went to al-Ma’muniyya High School for Girls in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. She enjoyed studying and took piano classes at the Salesian School in Jerusalem. When the 1948 War started, the family lost most of their belongings, but they took their piano with them. The piano is still in Amman today at the home of her niece, Taghreed.

In Jordan, Najjar attended Arwa Bint al-Hareth Elementary School for Girls in Jabal Amman and then Zein al-Sharaf Secondary School for Girls. Najjar was an active member of the Jordanian Student Conference, and in fact she became the first woman, in 1953, to be elected to its Executive Committee and remained a member of the conference until 1956. She was also active with the Palestinian student movement.

After graduating from high school, she traveled to Egypt and received her BA in sociology from Cairo University in 1960. She furthered her education in the United States, earning a master’s degree in journalism and development from Kansas State University in 1967 and then a PhD in mass communication from Syracuse University in 1975. Najjar’s dissertation was titled “Arabic Press and Nationalism in Palestine, 1920–1948.” She later published it as a book in 2005. During her years in the US, Najjar continued to study while working, earning certificates from Michigan State University in rural mentoring and leadership and from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), in administration and development monitoring and evaluation.

Career Path

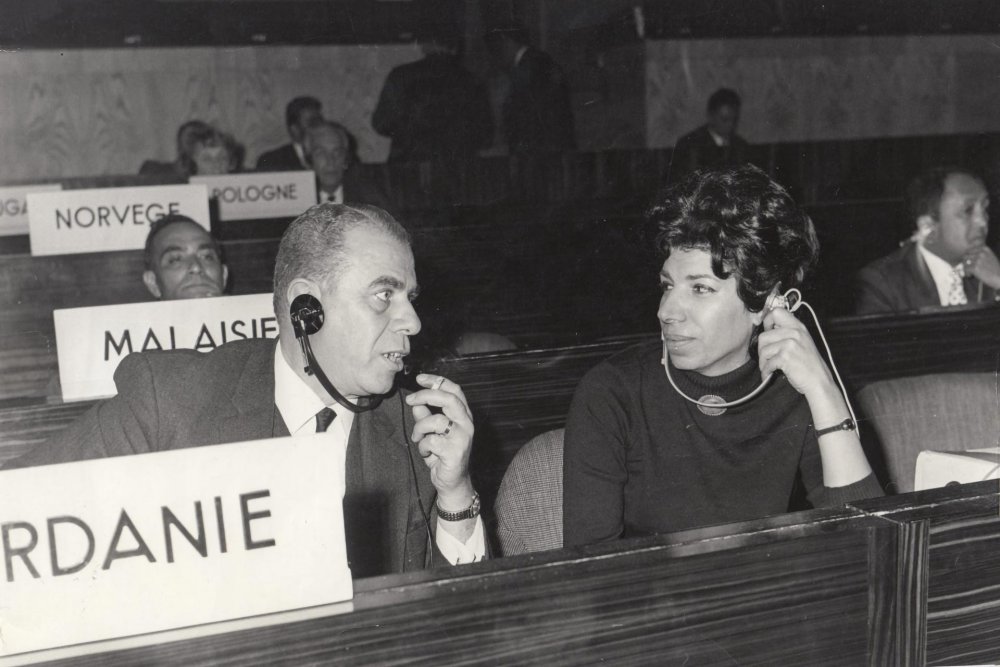

Najjar’s career path incorporated her interest in media, humanities, and culture. She worked with the UNDP’s Arab Office in New York, supervising programs and heading the rural women’s program in the Middle East and North Africa. In this capacity, she lived in different Arab countries, including Syria and Tunisia. In Yemen, she was Deputy Permanent Representative to the UN.

With expertise in social, media, development, and women’s issues, Najjar soon became an independent expert and researcher with several agencies, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome. She also worked for the Jordan foreign ministry’s International Section in Amman, which included cultural, educational, and media roles at the UNESCO in Paris. She assisted at the Ministry of Information, Ministry of Social Affairs, and the Ministry of Agriculture’s rural development section. These roles made her adept at social issues within the local societies in cities and villages she worked in.

In addition to her development projects and diplomatic missions, Najjar had a pivotal role in establishing the Kuwait News Agency (KUNA) in 1978, with a focus on the research department. She also had an active role in the literary domain and was a board member of the Jordanian Writers’ Society, the Arab Thought Forum, and the Jerusalem Forum.

She participated in several high-level conferences and workshops pertaining to media, gender, and social issues, as well as for planning, monitoring, and evaluation. She attended the World Conference on Women in Mexico City in 1975—the first international conference held by the UN to focus solely on women’s issues—and the World Conference on Women in Copenhagen in 1980. She also helped draft the regional’s report on the review of the Beijing Declaration in 1995.

Journalism and “The Press of Palestine”

Najjar established a name for herself as a thorough and meticulous researcher. She published extensively in various journals including al-Muntada, ESCWA publications, al-Dustour, and others. In 2005, she revised her original dissertation on the history of the Arab press and focused on the Palestinian press. Najjar analyzed the content of old newspapers, most of which she found at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and in the British Museum in London. This resulted in the publication of her first book, in Arabic, titled Press of Palestine and the National Movement in Half a Century (1900–1948). It garnered many awards, including the “Best Book of Human Sciences Award” in 2005 from the Philadelphia University in Jordan and the best Arab book at al-Ayyam Competition in Bahrain in 2006. It was also praised by the Ministry of Culture in Jordan. The book has since been taught as part of the curriculum in several Arab universities.

Najjar was passionate about journalism and said on more than one occasion that it would be difficult to stop her once she started talking about Palestinian press. She believed strongly in the importance of documentation in the Palestinian national movement.

Najjar was not only a researcher but also led workshops in journalism. She monitored Arabic-language newspapers and journals and analyzed changes in their coverage of events in different times. As an example, she noted how under the Ottoman Turks, the Arabic language was largely prohibited, yet despite that, al-Carmel weekly newspaper was founded in Haifa in 1908. It was the first platform that gave space to express Arab nationalism, and, as a result, it ran into problems with the Ottoman authorities a few years after. She highlighted the significant role of the Palestinian press had in historical periods, such as the political biweekly newspaper Filastin, which was cofounded in 1911 in Jaffa, al-Manar, al-Dustour, and al-Manhal. She called attention to the work of Khalil Beidas, founder of an-Nafais al-Assriah. She also gave prominence to several influential Palestinian figures, such as Khalil Sakakini, Issa el-Issa, Ibrahim and Fadwa Tuqan, ‘Ajaj Nuwayhed, Akram Zuaiter, and Issaf Nashashibi (whose house she visited and described in her accounts).

She regarded journalism as a mirror of a society. She believed that the Palestinian public was always interested in journalism, especially as of the mid-1930s, and this was the case even among those who could not read. She cited the example of fellahin who commonly gathered at cafés to listen to someone read the newspaper for them. At the time, as she was fond of pointing out, there were more than 40 Palestinian newspapers and journals in Palestine.

“al-Quds wa-l-Bint al-Shalabiyya” and Other Writings

Even as a child, Najjar loved to write.

In the fourth grade, she won an award for a composition she wrote in Arabic; her schoolteachers recognized her skill and always encouraged her to write. After her first publication in 2005, she went on to publish vivid accounts (of both Jerusalem and Amman) in a memoir style. In 2007, she wrote The Girls of Amman in the Old Times (also translated as Amman Schoolgirls of Long Ago). This book takes readers to the streets of Amman in the 1950s, as described through the high school narratives of adolescent girls.

In 2010, Najjar published al-Quds wa-l-Bint al-Shalabiyya (Jerusalem and the Pretty Girl). The book, which covers life in Jerusalem mostly during the British Mandate (1920–48), provides rich descriptions, historic details, as well as images of buildings, landscapes, professions, and families of Jerusalem prior to the Nakba. This gem of a book provides rich descriptions not only of Palestinian life, folklore, and heritage but also of the types of stones, flowers, castles, schools, libraries, and newspapers that existed prior to 1948. Almost like a family album, it mentions the names of Jerusalemite families, and references influential figures and intellectuals, including women. Written from the perspective of a girl born in Jerusalem, the book has been described as “the witness to Jerusalem, and Jerusalem is a witness to that girl.”4

By choosing the word “Shalabiya” (Arabic slang for cute) for the title, she attempted to reflect a social code that connects from one side and is understood on the other hand within the culture of this place in particular. A social system that brings Palestinians in this sense with the same set of behaviors and traditions that dignifies them from others, such as songs, food, and dressing style.5

The book was a response to former Israeli prime minister Golda Meir’s statement that “There was no such thing as a Palestinian people.” By skillfully weaving the rich multiplicity of Jerusalem life—the libraries, printing houses, and newspapers, not to mention the various people farmers, educators, writers, journalists, politicians, and ordinary residents including the schoolgirls and women of Jerusalem—Najjar amply demonstrates a thriving cosmopolitan city prior to 1948 in this book.

Other Publications

After al-Quds wa-l-Bint al-Shalabiyya, Najjar published three other books. The first, published in 2013, was Azouz Singing for Love: Palestinian Stories from a Thousand and One Stories (also translated as The Love Song of Azooz). In it, Najjar wrote short stories about Palestinian figures living under the Israeli occupation and their persistence in the face of the existential struggle. The second book, published in 2016 and titled Lifta Ya Aseeleh (Lifta, the Authentic), was an homage to Lifta, Najjar’s hometown. The third and last book, published in 2019, was Amman: A Trip Down Memory Lane (also translated as Amman: Between Love and Work).

The Memory of Lifta

In 2013, Najjar had expressed in her testimony that when she first went back to her village of Lifta after 1967, it made her very sad:

It’s such a beautiful country. It’s like a paradise lost. When they asked me again to go there I said no, because it made me so sad I became sick. I blamed myself for going to see the house in Lifta. I had a beautiful picture in my head, now it’s not the same anymore.6

She did, however, revisit Lifta in 2017. This time, the trip seemed to have been more cheerful, as the community members of Lifta invited her for an honoring ceremony after she launched her book on Lifta the previous year. During this trip, several awards and gifts were bestowed on her in recognition of her contributions. She archived the photos of this special trip on her webpage.

Her niece, the Amman-based publisher and children’s and young adult author Taghreed Najjar, shared with Jerusalem Story how her aunt had used the example of the village of Lifta “as a sample of what had happened to the displaced villages of Palestine.”7 The pain of one village, she believed, is indicative of the torment of an entire people.

Death

Aida Najjar’s niece Rima Najjar, a researcher and retired English professor, noted that her aunt was revered as an influential figure. Well-known families across Palestine, as well high-rank figures in Jordan including Princess Haya Bint al Hussein, lined up to pay their respects to the family when she died of multiple myeloma on February 5, 2020, in Amman.

Amti Aida had not married and had no children, but the line of close relatives, men and women, now grieving for her and proudly standing up to receive condolences at her azza (wake), is very long—Najjars and Hammoudehs from Lifta, Bseisos from Gaza, Abunimahs from Battir, Youneses from ‘Ar’ara, Toukans from Nablus, Annabs from Kafr Naja/Nablus, Kanaans from Anabta. . . . How my aunt would have relished such recognition! They will preserve her (our) Palestinian story, as well as her memory, her recollections and the oral history of other Palestinians that she has told so well.8

Sources

“2017: Talk: History of the Palestinian Press 1900–1948 by Dr. Aida Najjar.” [In Arabic.] Darat al Funun. YouTube, April 28, 2017.

Abu Samra, Mjriam. “The Palestinian Student Movement 1948–1982: A Study of Popular Organization and Transnational Mobilization.” University of Oxford, 2020.

Aida Najjar’s personal website.

Darat al Funun – The Khalid Shoman Foundation. “Aida Najjar: Palestine 1938 – Jordan 2020.” Accessed February 16, 2023.

Harhash, Nadia Issam. “The Growth and Development of Palestinian Women’s Movement in Jerusalem during the British Mandate (1920s–1940s).” Master’s thesis, Al-Quds University, 2016.

JANA Woman Magazine. “Dr. Aida Najjar in a Special Interview for JANA Woman Magazine.” [In Arabic.] Accessed February 15, 2023.

Al Jazeera. "The Passing of Palestinian Jordanian Writer and Journalist Aida Najjar at 81 Years Old.” [In Arabic]. February 5, 2020.

The Jordanian National Commission for Women. “Aida Najjar: I Long for Amman’s Old City, of Which the New Is ‘Jabal Amman.’” [In Arabic.] September 26, 2010.

Najjar, Aida. al-Quds wa-l-Bint al-Shalabiyya [Jerusalem and the Pretty Girl]. Amman: Al Salwa Publishers, 2010.

Najjar, Rima. “My Remarkable Aunt, Daughter of Lifta.” Rima Najjar page on Medium. February 9, 2020.

Al Salwa Publishers. “Aida Najjar’s Books.” [In Arabic.] Accessed February 15, 2023.

Zochrot. “Aida Najjar, Former Resident of Lifta.” June 26, 2013.

Notes

The Jordanian National Commission for Women, “Aida Najjar: I Long for Amman’s Old City, of Which the New Is ‘Jabal Amman’” [in Arabic], September 26, 2010.

The Jordanian National Commission for Women, “Aida Najjar.”

Zochrot, “Aida Najjar, Former Resident of Lifta,” June 26, 2013.

Nadia Harhash, “The Growth and Development of Palestinian Women’s Movement in Jerusalem during the British Mandate (1920s–1940s),” master’s thesis, Al-Quds University, 2016, 29.

Harhash, “Growth and Development.”

Zochrot, “Aida Najjar.”

Taghreed Najjar, interview with the Jerusalem Story Team, February 7, 2023.

Rima Najjar, “My Remarkable Aunt, Daughter of Lifta,” Rima Najjar page on Medium, February 9, 2020.