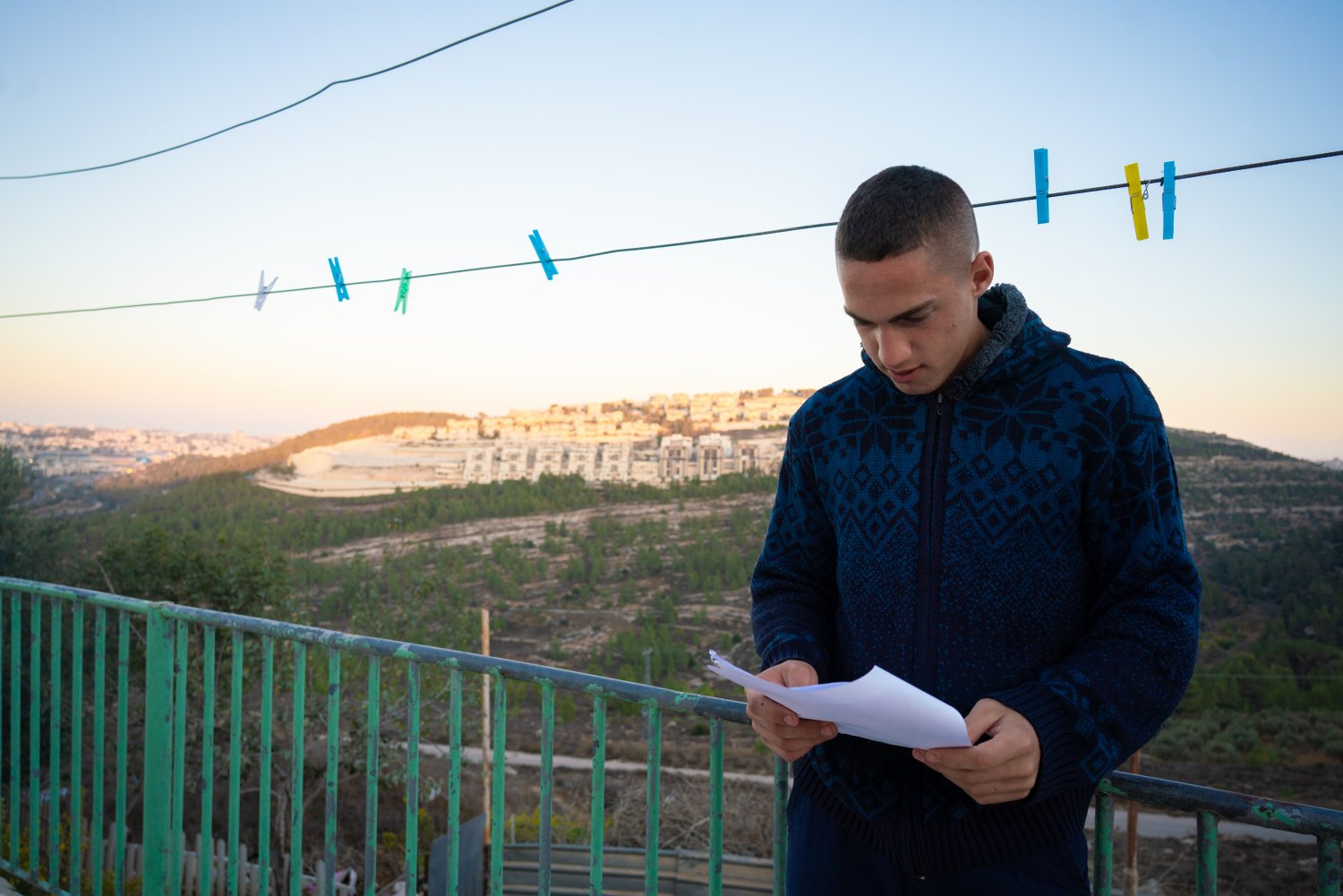

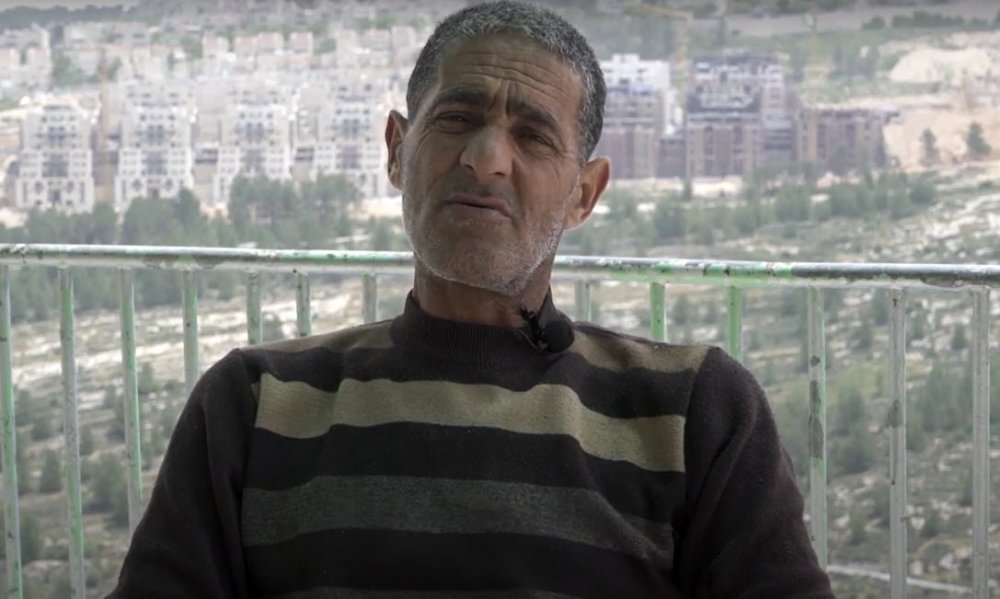

Today’s village of al-Walaja (meaning “the opening”) is located 8.5 kilometers southwest of Jerusalem, adjacent to the ‘Ayn Hanya spring, between Bethlehem and East Jerusalem.

Before 1948, the village was in a different location a few kilometers away, on the west side of Jerusalem on the side of a mountain. Its existence went back centuries, with documentary evidence of settlement and taxes dating back to at least the late 16th century.1 The Arab villagers owned 17,507 dunums of land as of 1944–45, of which 8,363 were cultivable. Agriculture was plentiful, aided by five groups of springs that flowed naturally nearby, creating wells that made it possible to raise some crops from rainfall only.2

On October 21, 1948, Haganah forces attacked al-Walaja at night and captured it, one of a string of villages captured in Operation Ha-Har to widen the corridor to Jerusalem.3 While this attack was initially repelled, much of the village, including the main built-up parts and 66 percent of its land,4 was later given to Israel as part of the armistice agreement of 1949.5 Its inhabitants were expelled, and many fled to caves on the remaining village lands that were on the Arab side of the armistice line. In 1950, Moshav Aminadav was established on the lands of al-Walaja by Yemeni Jews. In 1954, Israel destroyed what remained of the village to prevent the villagers’ return.6

With time, the inhabitants of al-Walaja, all refugees, gradually reestablished their village, which came to be referred to as “New al-Walaja” (al-Walaja al-Jadid), on the village lands that remained to them in the Jordanian-annexed West Bank.

In 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank (including Jerusalem), more than half of the land of “New al-Walaja” (13 percent of the original village) was incorporated into the Jerusalem municipality when Israel unilaterally expanded the city boundaries (see Where Is Jerusalem?).7 The villages call the area that now falls within the boundaries ‘Ayn Jawaizeh. Later, half of those lands were expropriated to build Jewish settlements.8 Today New al-Walaja is hemmed in by the Israeli settlements of Gilo (est. 1970) to the east, and Har Gilo (est. 1971) to the southeast. Both settlements are considered illegal under international law.

Gilo, as well as Har Gilo settlement, which lies east of the village, were built on expropriated land or land that was requisitioned by the military, which was formerly half of the land of annexed al-Walaja.9

The Jerusalem municipality provides no services to the village, nor does any other Israeli agency.10

In the mid-1990s, the Oslo Accords designated 97.4 percent of the remainder of New al-Walaja lands (those outside the city) as Area C, meaning they fell under sole Israeli control.11 This gave Israel the ability to obstruct further construction by denying building permits12 and demolishing many homes and farming structures in that part of al-Walaja that were or did get built.13