Wasif Jawhariyyeh (b. 1897 in the Old City of Jerusalem) was a musician and diarist, creating an invaluable account of late Ottoman–early British Mandate period life in Jerusalem from his vantage point balancing odd jobs, civil service, a rich social life—and as a confidante of the important Husseini family.

Family Background

Wasif Jawhariyyeh was born to Jiryis (Girgis) Jawhariyyeh and Hilaneh Barakat. Jiryis was a lawyer who also served as the mukhtar of the Old City’s Eastern Orthodox community and in the city council, and Hilaneh’s family was also from the Old City’s Greek Orthodox Arab community.1 Jiryis was friends with Hilaneh’s father, Andony Barakat, and after he passed away, Jiryis looked after Andony’s daughters. At the age of 40, he married Hilaneh, who had just reached puberty.

Wasif says that he was named after Wasif bey al-Adhem, “my father’s closest friend” and a judge in Jerusalem’s criminal court. The family lived in Haret al-Sa‘diyya, between Bab al-Sahira and the Via Dolorosa. Jiryis also bred silkworms, painted, and played the oud (although Wasif never actually witnessed this). Jiryis was a bit of an iconoclast, insisting that his sons memorize the Quran and also take on housework:

My father liked order and tidiness. He was a great socializer who taught and encouraged us to be righteous. For instance, when my sisters Afifeh, Shafiqa and Julia were married, he ordered my brothers Khalil, Tawfiq, Fakhri and me to help mother in all the housework, tidying away, cleaning, sweeping, and mopping the floor, laying out mattresses and bedding, and storing them away, whitening copper, and transporting water from the ground floor to the first floor, climbing forty-five steps. We even helped with meal preparation, to the great surprise of the neighbors who envied us for our housekeeping skills.2

Although Hilaneh could not read and write, her humor and voice run throughout Wasif’s recollections. In one section, Wasif describes the primus stove, a new invention. His mother hated it, he writes,

saying that it was too noisy and that she was not used to it. For example, someone would knock twice on the door of the main entrance, but my mother would not hear it because she would be near the stove. Then surprised to see the guest walking in, she would start cursing the stove and its inventor. I remember my father once coming home while my mother was fuming about it. She met him angrily and told hm, “I swear to God, Abu Khalil, this stove will make me run away! I swear it will make me renounce my religion and go straight to Temple Mount and become a Muslim. Damn it and damn the day you bought it.”

In the end, she surreptitiously traded the stove for a water jug and six cheap crystal glasses.3

The Jawhariyyeh family were experienced craftsmen, but they were also civil servants, and Jiryis was close to the prominent al-Husseini family, tending their lands. Hussein al-Husseini, later the city’s mayor, took Wasif under his wing and helped him get employment. This relationship meant that Wasif was privy to the goings-on of the city’s most well-heeled and at times entertained them with his music.

Music and Merriment

Wasif was nine when he became a barber’s apprentice under the tutelage of Matthia Abu Abdullah. He also carried out common health treatments, such as cupping and applying leeches, for the clientele. But the boy was much more interested in developing his musical talents, and although most of the members of his family played an instrument or were otherwise musically inclined, they discouraged Wasif from pursuing his music, to no avail. He recounts how he obtained his first real instrument:

Since I was extremely fond of music and singing, I invented an instrument out of a can of dye powder and took it along to the village of Beit Susin where I used to pluck its untuned strings, having no technical knowledge of how to play. . . . When [Moroccan field manager Hajj Mohammad Mu’een] saw my “tin instrument,” he said, “This one is no good, Wasif.” I was about nine years old at the time. “Go to the orange grove and ask Abu Salem to give you a dry pumpkin, and I will make you a beautiful tanboor like those we make in Morocco.”4

Hajj Mohammad proceeded to fashion him a long-necked strumming instrument out of a pumpkin, a piece of wood, and some animal skin, and then showed him how to play it. Wasif continued to learn new folk songs and increase his knowledge via the many musicians his father hosted at home or who visited Jerusalem. He was clearly talented, his verse replete with references to classical and contemporary writers.

At al-Dabagha School, a Lutheran institution, Wasif studied Arabic grammar, dictation, reading and arithmetic, German, and the Bible. After being beaten by a teacher there, Wasif’s father sought his admittance to the Dusturiyya School in Musrara, established by progressive educator Khalil Sakakini in 1909.

Wasif did not stay at the school long, however, as his patron Hussein al-Husseini prevailed upon Wasif to attend St. George’s School where he could learn English. He attended the school at the age of 15, until it was closed at the onset of World War I. Wasif never completed his education as a result. Salim Tamari writes:

Throughout his Ottoman years, and way beyond in his adult career, Wasif saw himself as a musician and ‘oud player above all else. When he sought employment in various government and municipal authorities, it was only to survive and release himself to his passionate obsession: the ‘oud and the company of men and women who shared his vision.5

After his father died,6 Wasif worked as a clerk in the Jerusalem Municipality, recording war donations. He then briefly served in the Ottoman navy before working as a court clerk in the Ministry of Justice. When his benefactor al-Husseini died in 1918, Wasif went on to help his widow manage their estate.7

British Rule

Both of Wasif’s brothers served in the Ottoman army in World War I, but in 1917, Wasif was working for al-Husseini, administering his grain trade between Palestine and Transjordan. In those days, trade was conducted in barges over the Dead Sea for lack of another route. The grain was delivered to feed the Ottoman soldiers and it was a brisk business.

Nevertheless, on December 9, 1917, when British forces took control of Jerusalem and occupied it militarily for three years, Wasif describes celebration:

I remember that day as being one of the happiest for the people. They were dancing on the pavement and congratulating each other [feeling that new freedoms were on the horizon]. Many young Muslim and Christian Arab men, most of whom had been conscripts in Jerusalem during the Turkish era, had changed their army uniforms into civilian clothes in a ridiculous fashion, fearing that the occupying British army might arrest them in their military uniforms and take them as war prisoners. . . . in Romema, we noticed how Jews in those quarters were keeping close company with the British soldiers who had made their way into the city, surrounded on both sides of the road by Jewish young ladies who accompanied them, chatting to them in English with smiles on their faces and giving them an excessively warm welcome, until they went their separate ways.

After Balfour’s declaration and sinister promise, we would remember back to this warm welcome of theirs. We did not realize that, thanks to this occupation, Zionist dreams would come true.8

In 1918, Wasif’s brother Khalil and his business partners opened a café and bar in the Russian Compound in Jerusalem. The café became very popular. As Wasif describes, “Arak glasses were arranged on a special tray among delicious mezze dishes presented in a variety of small matching plates and stylishly served to the customer by the waiter with a glass of ice-cold water. This was unseen in Jerusalem at the time.”9

Wasif accompanied numerous singers at the café, and also played at elaborate parties—one lasting a week in the Jewish Quarter. At another, Jerusalem’s British military governor, Ronald Storrs, asked him to sing a cheeky song about the Arab denouement and impending Zionist control, after which the officer laughed heartily. It is through Wasif’s diaries that we also learn of the various mistresses of the city’s well-heeled, as well as interactions between different communities and how they socialized.

Wasif’s mother died of pneumonia in 1920, leading him into a period of increased debauchery and perhaps depression. Wasif refers to his home as a “barracks” where he and his brothers came to sleep in-between their drunken nights. At 25, determined to change his life, Wasif traveled to Beirut for one month; as a man of modest means, he was fascinated with the city’s delicacies and urban life, so he referred to himself as “a Bedouin in New York.”

Wasif married Victoria Saad, the daughter of Saliba Saad, who owned a hotel in Jericho during World War I. They promised themselves to each other in 1919 but did not have the savings to make the marriage official until March 9, 1924. Victoria, by a stroke of luck, had been educated by the patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church, who said she reminded him of his deceased daughter. The newlyweds lived in the isolated Nicoforio house, which belonged to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate and overlooked the Jaffa Gate from outside the walls of the Old City. In his diaries, Wasif describes in detail the various communities that had emerged outside Jerusalem’s city walls since the late Ottoman period (see The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before “East” and “West”).

In 1929, Wasif was appointed fiscal manager for the city of Jerusalem, in addition to his job as head of the property and property tax appeals committees. In this way, he seemed to have resolved the earlier struggle between his music and his need to make a living. When Wasif was asked to become head of the music section at the new radio station in Jerusalem, he declined, saying, “I decided to consider art as a religion, which I would follow solely for the love of it, just as I had been raised to.”10

Danger Leads to Flight from the City

Tensions between Arab and Jewish residents of Jerusalem rose throughout the 1920s and 1930s as British Mandate officials allowed for the immigration of tens of thousands of Jews to Palestine. This angered Palestinians, whose lands were being confiscated and given to Jews, and who were losing valuable resources, including employment.

In his diaries, Wasif describes strikes in 1931 and October 1933,11 and then the “great strike of 1936” against British occupation and the influx of Jewish immigrants.12 As “bloody battles”13 escalated in Jerusalem throughout the 1940s (see The West Side Story), especially in the New City, Wasif and his family were terrified:

Our house was in zone 2 which had been encircled with barbed wire. A [British] military base was set up on the eastern side of the wall around our house. We did not like the presence of the army. They were watching the Arabs on the side of Jaffa Gate and the Tower of David, and Jews in the Montefiore neighborhood. They never stopped firing day or night, and our home became but a target. It was also hard to reach our home from the Saint Julian’s Way entrance to the zone. . . . For any of us to get to the house once inside the secured zone we had to walk past the King David Hotel, which posed a risk as this area was exposed to fire by Jewish settlers of the Montefiore neighborhood, who shot at anyone who walked there. They often shot at us and at our son-in-law Zuhdi. We only survived these battles by a miracle.14

In this dangerous atmosphere, Wasif’s health failed, and his doctor advised him to go somewhere else to recuperate. Despite being forced to leave behind the Jawhariyyeh collection, which included pieces of art and china that Wasif had collected over 30 years, the family fled to Quruntal monastery in Jericho. Their Jerusalem home was turned over to the French consulate in the interim, with a pledge to return it unharmed once the family returned. The consul even obtained a letter from the Jewish Agency and Arab Higher Committee agreeing that the house was under French protection—a letter that prevented a Haganah takeover, but did not mean the home was returned to its rightful owners. While the events that unfolded are not entirely clear, Wasif indicates rather understatedly that the house—and presumably its museum-like contents—moved to “Jewish ownership” after the establishment of Israel.

The family fled Jerusalem on April 18, 1948. After also leaving the monastery, where they had planned to stay only a matter of weeks, Wasif and his wife and children joined the throngs of Palestinians in Jericho who had fled or been forced out of their homes across Palestine. Wasif served for a period as part of a relief committee, but soon grew frustrated with what he said was theft and deception. He subsequently decided to leave for Beirut once more.

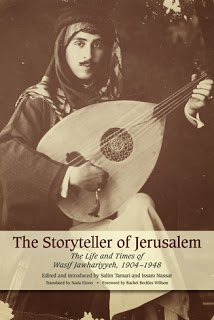

Wasif began compiling his memoirs, now available in Arabic and English, while in Jericho, and he continued writing in Beirut where he lived in the 1960s.15 The original diaries are handwritten in three volumes, covering the Ottoman period, the British Mandate, and a brief section on his life in Beirut. Versions areavailable in English and Arabic. The English version is a condensed edited one available under the title The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawharriyeh, 1904–1948 (Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar, eds., Olive Branch Press, 2014). According to an introductory note in the English version, the complete, original handwritten memoirs and accompanying photo albums are archived at the Institute for Palestine Studies offices in Ramallah.

Wasif goes into considerable detail describing shared religious and nonreligious events among diverse Palestinians in Jerusalem that paint a picture very different from the accepted narrative of Ottoman oppression of religious minorities on the eve of World War I. These accounts also challenge the narratives that Jerusalem was a space of segregated religious communities that competed politically.

Spanning six decades from 1904 to 1968, Wasif’s diaries are considered an important record of the time from a social and communal vantage point. The Guardian named them as one of the top 10 eyewitness accounts of 20th century history.

The diaries are also accompanied by a collection of more than 900 images designed to accompany the diary, but they had to be produced in 7 albums because they could not fit in a single one. According to historian of modern photography Issam Nassar,

. . . the Jawhariyyeh albums are important because they bear witness to the loss of their original subject in a material sense, that is, Jerusalem in a time of more or less peaceful coexistence. Images from Palestine before its conquest have become foundational elements in the collective nostalgia of the Palestinians.

The albums are chronologically organized and contain photographs of leaders, rulers, elites, and locations. Together they fueled a powerful narrative of loss and longing for homeland that was central to the identity construction of the Palestinians in exile . . . Jawharriyeh kept a separate notebook for each of the albums in order to describe the photographs. In addition to the pictures themselves, these notebooks are valuable sources of information about the period.16

Besides his diaries, Wasif left behind collections of musical notes, poetry, and a collection of proverbs that was used by his daughter, Yusra Arnita, in a volume that she subsequently published. He also had a son named George.

Death

Wasif Jawhariyyeh, Jerusalem’s musician and poet, died in exile in Beirut in 1972.

Notes

Salim Tamari, “Jerusalem’s Ottoman Modernity: The Times and Lives of Wasif Jawhariyyeh,” Jerusalem Quarterly 9 (2000): 5–27.

Wasif Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948, ed. Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2014), 71.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 107.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 94.

Tamari, “Jerusalem’s Ottoman Modernity.”

Jawhariyyeh’s diaries are not clear as to the date of his passing.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 207.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 194–95.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 209.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 379.

Wasif describes a strike across Palestine, with a Jerusalem demonstration led by Musa Kazem al-Husseini that clashed with British government forces at the New Gate. Another demonstration was held on October 26, 1933. Al-Husseini was injured during these strikes and was afterwards bedridden until his death. Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 366.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 372.

Jawharriyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 414.

Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem, 414.

Tamari, “Jerusalem’s Ottoman Modernity.”

Issam Nassar, “The Wasif Jawharriyeh Collection: Illustrating Jerusalem during the First Half of the 20th Century,” in Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840–1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, edited by Angelos Delanchanis and Vincent Lemire (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 387.