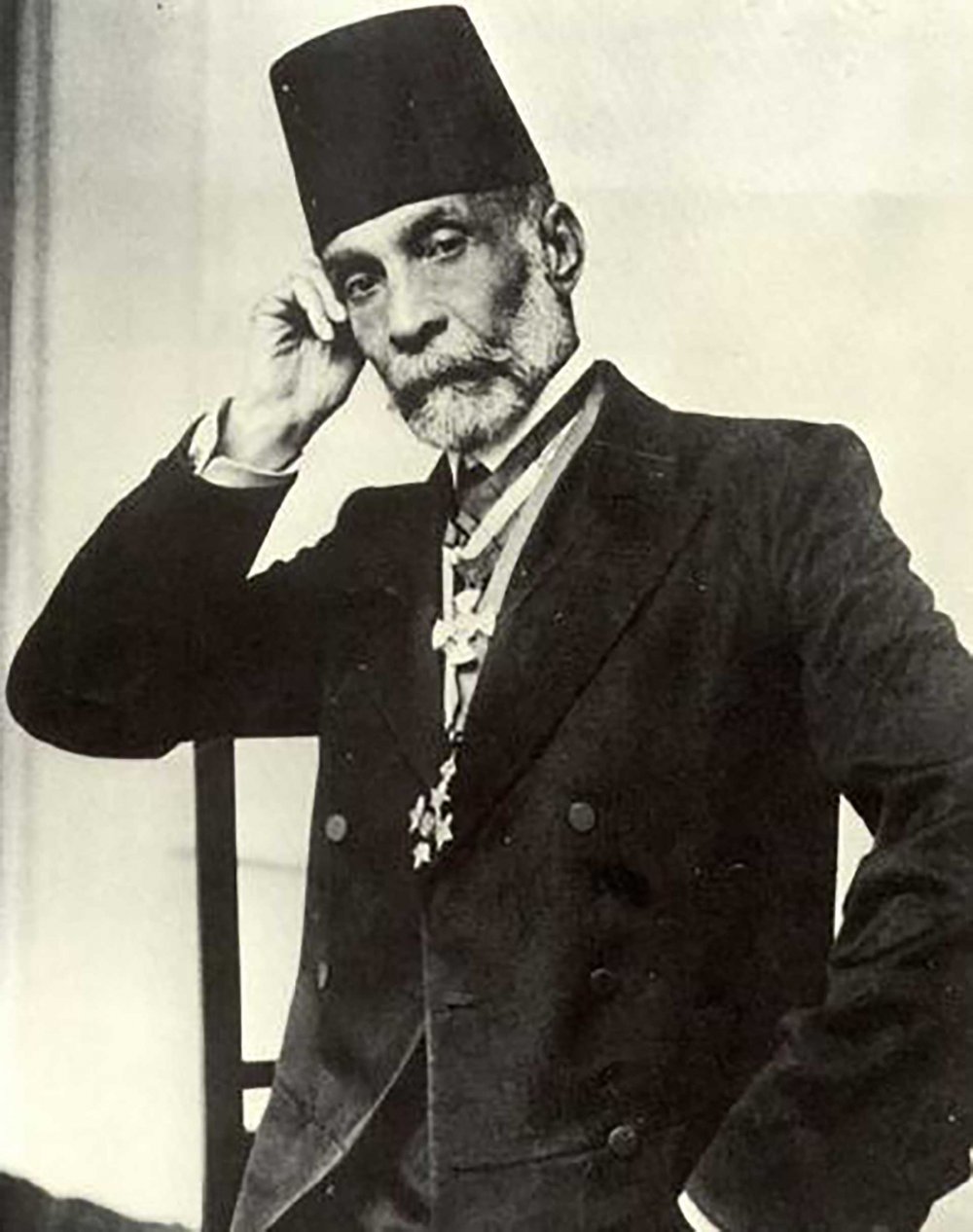

Musa Kazim al-Husseini served as the first mayor of Jerusalem after the British conquest of Palestine and went on to become a leading figure in the Palestinian nationalist movement against British and Zionist rule.

Family Prominence and Pre-Mandate Career

Musa Kazim was born in Jerusalem in 1853 into one of the city’s most notable families. Members of the prestigious Husseini family had held important political, religious, and administrative positions in the city since the 19th century. Musa Kazim’s father, Salim al-Husseini, had served as mayor of Jerusalem between 1882 and 1897, leaving a legacy of public service and devotion to the city that would be continued by his descendants. In his diaries, renowned Palestinian storyteller Wasif Jawhariyyeh describes Salim as a treasured icon of the city:

Hajj Salim al-Husseini rose to a high status in the country, and the Ottoman government had to bear him in mind, given his patriotic stances and the love that people—particularly the farmers—had for him. He was, God bless his soul, a member of the Administrative Council of Jerusalem and head of Jerusalem’s municipality for twenty-two years and truly served the city. It was he who had the public sewage system built within the wall. He is also responsible for paving the streets of Old Jerusalem, which he both conceived and saw through, thus transforming the city into a model for cleanliness, beauty, and marvel, particularly for foreigners who used to come to visit its holy sites.1

Musa Kazim and his younger brother Hussein Salim were thus exposed to Jerusalem’s political elite from a young age. While little is known about Musa Kazim’s childhood while attending Jerusalem’s Rashidiyya School, a religious primary school,2 he was admitted at a young age to one of Istanbul’s most prestigious educational institutions, the Maktab Sultani, which “prepared its students to occupy important posts in the Ottoman administration.”3 There, he excelled as a student, achieving third place among all the students from the Arab world.4 His first appointment at the age of 27 was as a senior clerk, a bashkatib, in the Department of Health in Palestine, but he proved his excellence as an administrator and, one year later, was promoted to the rank of qa’im maqam—the title assigned to the governors of provincial districts in the Ottoman Empire—and traveled between Jaffa, Safad, Acre, Akkar (current-day Lebanon), Ajlun (current-day Jordan), and Harem (current-day Syria).5

Five years later in 1896, he was promoted again to the rank of mutasarrif, a position he held until 1913. As mutasarrif, Musa Kazim traveled extensively across the provinces of the empire, including Hawran in southern Syria, eastern provinces in Anatolia, the large confederation of tribes in current-day southern Iraq/northern Kuwait known as al-Muntafiq, and the provinces of Asir and Hijaz in current-day Saudi Arabia and Yemen.6 Altogether, Musa Kazim spent 35 years traveling throughout the Ottoman Empire in several high-ranking administrative roles, earning him considerable repute both in Istanbul and in Jerusalem, his hometown. Indeed, he was highly trusted by the Ottoman administration, and his illustrious career earned him the prestigious title of Pasha in the early 20th century, conferred on him by the sultan himself.7 Thereafter, he became known as Musa Kazim Pasha.

By the time World War I broke out in 1914, the 61-year-old Musa Kazim had returned to Jerusalem and retired. He spent the four grueling years of the war at home in the city, but once Britain promised Palestine to the Zionists in November 1917 and occupied Jerusalem one month later, he swiftly returned to the world of politics. This time, though, he returned not as an Ottoman administrator or governor, but as mayor of Jerusalem and leader of the Palestinian nationalist movement against British and Zionist policies.

A Brief but Tumultuous Mayorship

In 1909, Musa Kazim’s brother Hussein restored the family’s hold over the seat of mayor after their father Salim’s term, which ended in 1897.

But Hussein’s mayorship during the war years was dramatic. After British forces expelled the Ottomans from Jerusalem in the first days of December 1917, Hussein was forced to surrender the city days later, on December 9. He handed over the keys of the Old City to General Edmund Allenby, who marched through its gates on December 11, announcing Britain’s official occupation of Palestine.

Hussein died shortly after in January 1918, at which point British authorities dissolved the city’s municipal council and appointed one consisting of two Muslims, two Christians, and two Jews. To appease the Arabs of the city, they also appointed Musa Kazim as mayor of Jerusalem.8

In the early months of 1918, and with the increasing threat of British, French, and Zionist takeover in the region, the new 65-year-old mayor of Jerusalem got busy fast. He joined his nationalist compatriots in political activism against Jewish immigration to Palestine and against European plans to sever it from Greater Syria. These activists were part of several Muslim-Christian Associations that formed in Palestine’s major cities, the first of which appeared in Jaffa on May 8, 1918. Musa Kazim was a critical figure in the Jerusalem association. In fact, one of the first things he did as mayor was to refuse to make Hebrew an official language of the Jerusalem Municipality in protest at increasing Zionist influence in Palestine, which was evidenced in British Mandate policy.9

During this time, Musa Kazim joined the newly founded Pro-Jerusalem Society, established in 1918 by British Military Governor Ronald Storrs and architect Charles Ashbee, for the “preservation and advancement of the interests of Jerusalem,” including its antiquities, architectural standards, and cultural institutions.10 Musa Kazim was thus a pragmatic yet resolute leader in these early years of his political career in Jerusalem, on the one hand, taking daring political stances against the city’s new occupiers, while also participating in their elite initiatives.

On November 3, 1918, Musa Kazim led a demonstration in Jerusalem of Muslim and Christian Palestinians against the Jewish celebrations which took place one day prior on the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. In a petition submitted to Storrs, Musa Kazim and his compatriots made the Muslim-Christian Associations’ demands clear: independence, opposition to the Balfour Declaration, and opposition to mass Jewish immigration to Palestine.11 That Musa Kazim led these initiatives in Jerusalem did not bode well for him with British forces, but it earned him increased import as a leader among Palestinians.

This dynamic persisted throughout 1919, especially in the lead-up to the US-led King–Crane Commission, which was set to submit its report on the conditions in the former Ottoman provinces to the Paris Peace Conference later in the year. With word of this, Musa Kazim mobilized members of Muslim-Christian Associations across Palestine and resolved to push for Palestinian demands. In early 1919, he led a demonstration starting at the al-Aqsa Mosque complex before visiting different foreign consulates in the city to present petitions laying out Palestinian grievances.12 He spent the remainder of the spring and summer meeting with compatriots and delivering demands to European authorities in Jerusalem; the Zionists were doing the same in advance of the commission.

Despite these efforts, and despite the King–Crane Commission’s report submitted to the Paris Peace Conference in August 1919, Britain’s Mandate for Palestine was approved at the conference with its attendant commitment to the Zionists, and plans were set for its official establishment in 1920. Musa Kazim did not back down. He organized another anti-Zionist demonstration on February 27, 1920, to which Britain responded by banning demonstrations in March.13 But weeks later, as Palestinians were preparing for the annual Nabi Musa festival, which coincided with Christian and Jewish holidays that year, they gathered in the Old City on April 4 to hear speeches by the city’s leading nationalists, including Musa Kazim, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, and Aref al-Aref. The trio spoke impassionedly about the unity of Greater Syria and opposition to Zionism and Jewish immigration, declaring Emir Faisal as king of a united Syria with Palestine as its southern province.14 The ensuing riots, known as the Nabi Musa Riots, lasted for four days, rocking Jerusalem.

Palestinian nationalists in the city, including its mayor, Musa Kazim, submitted a petition calling for the resignation of military governor Storrs.15 Meanwhile, British Mandate forces accused Musa Kazim of orchestrating the riots, though he insisted that it was not the Palestinian Hebronites who sparked the violence—as charged by British authorities—but the Jews.16 Storrs thus swiftly dismissed him from the mayorship that same month, replacing him with one of his political adversaries, Raghib al-Nashashibi. In his memoir, Storrs described the British reactions to the riots:

The Easter troubles incidentally brought to a head the question of the Mayoralty of Jerusalem. Musa Pasha Kazem al-Husseini, who as Mayor should have represented impartially all three communities, had recently been impelled as head of one of the chief Arab families to make himself leader and spokesman of the opposition to the Mandate. I had met him one afternoon marching before a rabble to demonstrate against the Zionist Offices, and bade him take them and himself home lest trouble should arise. The same evening I warned him that he must make his choice between politics and the Mayoralty. During the riots he became first intractable and then defiant, and I informed the Administration that I proposed to dismiss and replace him forthwith . . . I therefore sent for Ragheb Bey el-Nashashibi, an able and determined ex-Deputy of the Ottoman Parliament, offered him the Mayoralty and requested him to confirm his acceptance in writing on the spot. I was glad I had done so when twenty minutes later I intimated to Musa Pasha (not without regret, for he had rendered service and proved himself on occasion a courteous Arab gentleman) that the time had come to make a change. The Pasha said: “Your Excellency is free to act, but I would recommend you to wait, for I have certain knowledge that no Arab will dare to take my place.” I handed him Ragheb Bey’s letter. When he had read it he rose, thanked me for my past support, assured me of his continued friendship, shook hands and walked erect and slow out of my office.17

The dramatic dismissal drove a deeper wedge between the city’s notable families and thus, the Palestinian nationalist movement.

Leader of the Arab Executive

The aftermath of the April 4–7 riots and dismissal of Musa Kazim wrought disaster for the Palestinian nationalist movement. Later that month, representatives of the Paris Peace Conference met at a palace in San Remo, Italy, from April 19 to 26 and confirmed the partition of Greater Syria into mandates, including Britain’s Mandate for Palestine. Britain also assigned Herbert Samuel, a self-proclaimed Zionist, to serve as the first High Commissioner for Palestine and to see to the implementation of the Balfour Declaration. In fact, Samuel’s administration announced in August 1920 a quota of 16,500 Jewish immigrants for his first year in office.18

Representatives of the Muslim-Christian Associations protested the appointment of Samuel, and even British military generals Edmund Allenby and Louis Bols warned against the controversial decision—the latter explaining that the news was received by the Arabs with “consternation, despondency and exasperation.”19 Allenby predicted the appointment would spark violence, saying that the Arabs would view it “as handing the country over at once to a permanent Zionist Administration.”20 In June 1920, one week before Samuel’s arrival in Jerusalem, members of the Muslim-Christian Associations sent a letter to Bols explaining their position:

Sir Herbert Samuel regarded as a Zionist leader, and his appointment as first step in formation of Zionist national home in the midst of Arab people contrary to their wishes. Inhabitants [of Palestine] cannot recognise him, and Muslim-Christian [Associations] cannot accept responsibility for riots or other disturbances of peace.21

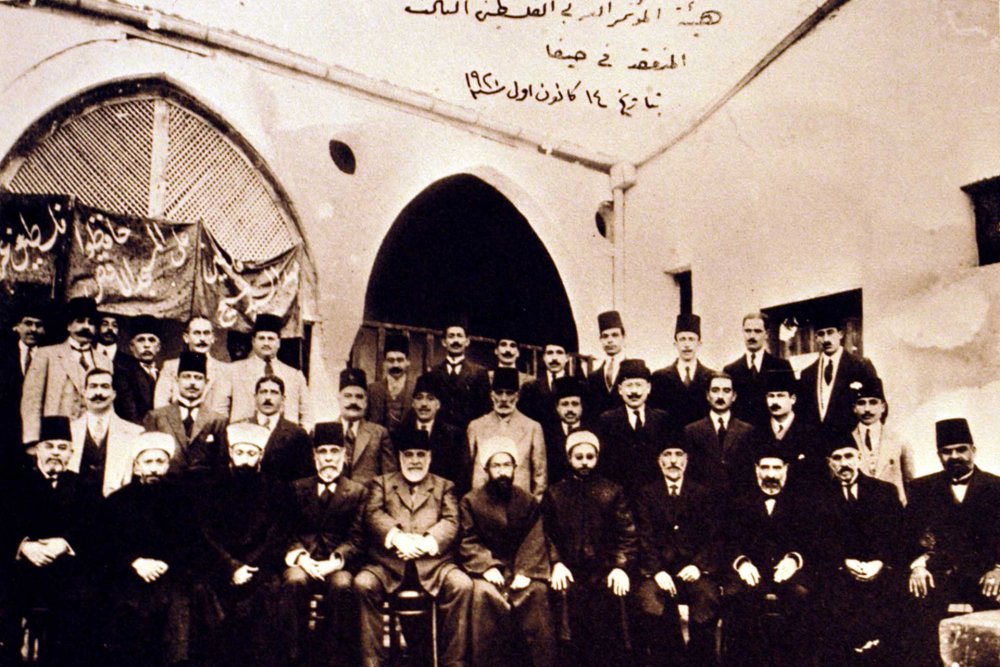

Nonetheless, Britain went ahead with its appointment of Samuel, and though violence did not break out as Allenby predicted, representatives of Muslim-Christian Associations across Palestine met at the Third Palestine Arab Congress in Haifa in December 1920 to organize a Palestinian position against the troubling developments. The congress resolved to form an executive committee of nine members, electing Musa Kazim as president and chairman. The committee, known as the Arab Executive, functioned for 10 years, even though Britain never recognized it.

Throughout its decade-long tenure, Musa Kazim remained the committee’s chairman and maintained firm opposition to British policy. He and other members of the committee worked toward fulfilling the demands of the Muslim-Christian Associations and the Arab Executive: calling for Palestine’s independence as part of an Arab state and for the formation of a national assembly in Palestine that would include Jewish representation. The committee also emphasized its rejection of the Balfour Declaration and Jewish immigration. In fact, the Fourth Palestine Arab Congress met in Jerusalem in May 1921 and tasked Musa Kazim with leading a delegation of representatives from the Arab Executive to London that summer to make these demands clear, albeit to no avail.22

Though Samuel allowed for the formation of the Supreme Muslim Council in December 1921, appointing the young and popular Hajj Amin al-Husseini as its president, tensions between Musa Kazim and British Mandate leadership in Jerusalem continued to rise. In addition to Britain’s refusal to recognize Palestinian demands, this was exacerbated by the mandate government allowing al-Nashashibi to form an opposition bloc (al-mu‘arada) to the main bloc (al-majlisiyyin) headed by Musa Kazim.

And in 1922, Samuel proposed the formation of a legislative council (as well as an advisory council in 1923), but Musa Kazim and the majlisiyyin opposed it. Historian Philip Mattar explains:

They feared that acceptance of the council was tantamount to acceptance of the British mandate (which was approved in July 1922 by the League of Nations) and support for the Jewish national home. They also considered unfair the council’s composition, which reserved only 43 percent—10 out of 23 positions (11 British, 2 Jewish)—to the Arabs, who then constituted 88 percent of the population. Finally, they felt that the council was legislatively powerless, especially regarding such constitutional matters as Jewish immigration.23

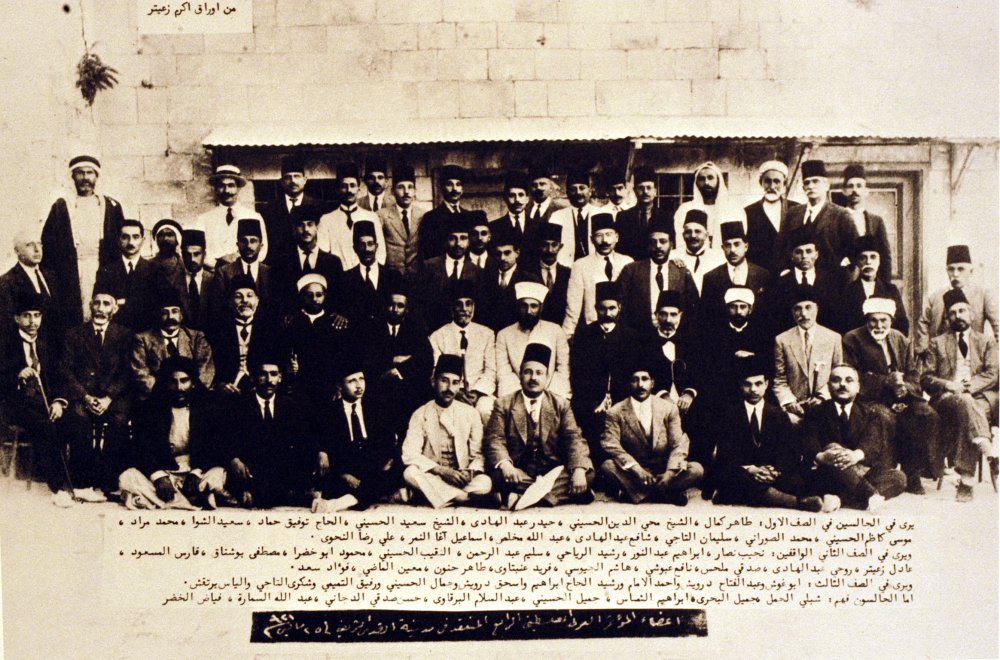

The 1920s were thus frustrating years for Palestinian nationalists, certainly for members of the seven Palestine Arab congresses held between 1919 and 1928 and that sent delegations to London led by Musa Kazim. On the one hand, their ongoing efforts to influence British policy in Palestine in Jerusalem and London regarding their plans to establish a Jewish national home there were fruitless. On the other, rivalries between Jerusalem’s elite families continued to divide the already largely ineffectual movement, further discrediting them in the eyes of British and Zionist forces. Nonetheless, during these years, Musa Kazim remained the president of the Arab Executive, a leading figure in the Jerusalem branch of the Muslim-Christian Associations, and elected representative of Jerusalem to the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh Palestine Arab congresses.24

Moreover, even when Palestinian nationalists put aside their differences for the greater good of the movement, their efforts were equally quashed by British authorities. At the Seventh (and last) Palestine Arab Congress, held in Jerusalem in June 1928, representatives in attendance decided to form a united front among the majlisiyyin and the mu‘aridin with Musa Kazim as their leader.25 The president of the Arab Executive thus joined forces with his nemesis, Mayor Raghib al-Nashashibi. Nevertheless, the British and Zionist schemes in Palestine went as planned, leaving the Palestinian leaders even more exasperated.

Indeed, after the violence of the August 1929 al-Buraq Uprising, Musa Kazim led a united front in Jerusalem and London against British accusations of Arab violence. On September 1, 1929, High Commissioner John Chancellor proclaimed that the previous month’s riots were provoked by Arabs, to which Musa Kazim submitted the following retort later in the month on behalf of the Palestinian leadership in Jerusalem. He expressed dismay at the High Commissioner’s accusation and requested an impartial commission of inquiry on the summer’s events:

Palestine Arabs read with astonishment and regret your Excellency’s Proclamation dated 1st instant [sic]. None anticipated that [sic] widely known facts admitted by Government, that most Jews were selfarmed [sic], that Government armed many Jews, that there were no mutilations among Jewish casualties even at Hebron, as British Public Health Authorities declare, that certain Arabs were mutilated by Jews, that Jewish mobs killed isolated Arab women and children, that first murders of women and children were committed by Jews against Arabs, that even disciplined British soldiers shot Arab men, women, and children in their homes and beds at Sour-Baher and elsewhere, that troubles in Palestine, past and present, are directly caused by British Zionist Policy, which aimed at annihilating the Arab Nation in its country in favour of reviving a nonexistant [sic] Jewish Nation, facts all of which would be thwarted by a hasty untimely proclamation. Your Excellency knows that Palestine Arabs lost everything to fear the loss of anything; therefore British troops will find them unarmed submitting to any havoc. If there remains any sense of Justice, to which Arabs are entitled, they insist that an impartial inquiry be made by outsiders, whose sense of Justice is not curbed by Zionist influence. In the two previous inquiries made in similar conditions, by unbiassed British Commissions, Arabs gratefully proclaim they were relieved by having their political agonies and noble national aims unfolded. Arabs strongly believe that similar inquiry will relate to the world a more truthful story of their condition and these troubles than that depicted in this proclamation issued before giving them any chance to be heard. Then the world will see that Jews, whose aggressions have surpassed political aims to religious ones, whose provocations lately became insupportable, as admitted by Government, whose atrocities do not fall short of this proclamation’s accusation against Arabs, were responsible for the present troubles together with the policy supporting them. This proclamation should be succeeded and not preceded such impartial inquiry, and we are sure that reconsideration of the situation will lead Your Excellency to a more rightful judgement.26

The statement was signed by “President Arab Executive, Mousa Kazim El-Husseini.” While it is unknown to what extent Musa Kazim’s statement influenced the High Commissioner, on October 25, 1929, the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929 (known as the Shaw Commission) began taking testimonies from witnesses in preparation for the report that it published on the events in March 1930. However, the commission’s report was primarily based on materials submitted by mandate officials, rendering the report’s recommendations skewed. Indeed, despite Musa Kazim’s statement and eyewitness testimonies to the contrary, the report concluded: “The outbreak in Jerusalem on the 23rd of August was from the beginning an attack by Arabs on Jews for which no excuse in the form of earlier murders by Jews has been established.”27

Musa Kazim led his final delegation to London in late March 1930, following the publication of the Shaw report. The delegation consisted of six members of the Arab Executive, including Raghib al-Nashashibi and Hajj Amin al-Husseini. Mattar recounts that on January 9, two months prior to the delegation’s departure, the Arab Executive elected Hajj Amin to lead the delegation instead of the 77-year-old president who, though widely respected, was not as popular as the younger Husseini. This upset the seasoned elder leader, and two weeks later, Hajj Amin himself ceded the leadership of the delegation to Musa Kazim in an act of respect and for the sake of the movement.28

This show of unity among Palestinian nationalists before British colonial leadership was unprecedented given years of enmity between Jerusalem’s leading families. Yet even the more moderate requests they made of the British government in London were denied. In addition to calling for restriction of Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews, the united Palestinian delegation requested the formation of “a democratically elected legislature proportionally representing Arabs and Jews, under a British High Commissioner who could veto legislation that he considered inconsistent with the mandatory obligation.”29 British authorities simply did not wish to cede any power in Palestine to the Palestinians, and as a minority in Palestine, Zionist Jews would not accept a democratically elected legislature.

Musa Kazim sent a telegram to the Arab Executive in Jerusalem following the delegation’s failed mission, in which he wrote: “The Arab cause in Palestine will not find a just solution at the hands of the British government which is under Zionist influence.”30

Musa Kazim’s Final Radical Years

Musa Kazim returned to Jerusalem from London convinced that Britain would never fulfill Palestinian nationalist demands, so he took matters into his own hands. While still leading the Arab Executive, he formed and headed the National Fund in Jerusalem in September 1932 as a way to “raise funds in order to buy lands in Palestine to keep them from falling into Jews’ hands.”31 Alongside six other members of the founding committee, the National Fund committed to “allocate all funds that were and will be collected to the National Fund for those who purchase in Palestine”; and to “form an Arab company called ‘The Arab Company to Save the Lands of Palestine,’ and for the committee to contribute all the funds of the National Fund to this company.”32

To be sure, the National Fund would counter the work of the Jewish National Fund (JNF), which had been increasing its purchases of Palestinian lands over the years and renting them to an increasing number of Jewish immigrants to the country. Musa Kazim thus joined his compatriots in ramping up anti-Zionist efforts without resorting to the British for help. As an example, in April 1929, the JNF purchased lands in the village of Wadi al-Hawarith, located on the coast in the Tulkarm district, at an auction, and as a result, the court ordered Palestinians residing on the land to vacate it, but they refused and appealed the order. Following two years of legal battles, during which the JNF built a Jewish settlement and planted thousands of trees in the village, the court ruled in favor of the JNF.33

Villagers of Wadi al-Hawarith, who were expelled from the land in June 1933, took their plight to Palestinian nationalist leaders. On June 27, Filastin newspaper published the following call by Musa Kazim to the “noble Arab people regarding the nakba of the Arabs of Wadi al-Hawarith.”34 He began by stating the reality that economic, political, and administrative forces are contributing to the creation of a Jewish national home and that

the cause of Wadi al-Hawarith is the greatest proof and strongest indication of this. The disaster of Wadi al-Hawarith is the disaster of Palestine in its first stages, and if the nation does not stand in the way of this first practical step of the policy of evacuation and extermination, the coming steps will be harsher in impact and stronger in effect.

He went on to describe the sacrifices made by the Arabs of Wadi al-Hawarith and claimed that it was time for the Arab nations to come to their aid: “We call on all nations to each form special committees to collect continuous assistance for the brave Arabs of Wadi al-Hawareth.”35 Musa Kazim signed it as president of the Arab Executive and the National Fund.

Beyond reaching out to the Arabs for help regarding Wadi al-Hawarith and the Palestinian cause more broadly, Musa Kazim and his compatriots mobilized Palestinians in new protests in late 1933 against Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews; they did so despite a British ban on demonstrations issued on October 10.36 Musa Kazim’s decision to take to the streets in protest of British and Zionist policies also had to do with the return of his son Abd al-Qadir to Jerusalem from the American University in Cairo one year prior in 1932. Evidently, Abd al-Qadir’s “youthful radicalism and impatience had an influence on his father and helped bring a mood of confrontation.”37

On October 27, 1933, the first demonstration in Jaffa began, and British police met it “with live fire,” leading to 11 deaths and 20 injuries, including 80-year-old Musa Kazim, who was “beaten to the ground by baton-wielding mandate police.”38

But the protests did not end that day and instead spread to Haifa, Nablus, and Jerusalem, leading to dozens of casualties. The Arab Executive declared a three-day strike, and demonstrations spread as far as Damascus, leading the High Commissioner to reinstate martial law through the Palestine Defense Order-in-Council, first issued in 1931. The decree “legalized wide censorship, arrests without warrant, and detention without charge or representation, deportation without appeal, and secret military courts”—the same policies under which the Israeli occupation governs the Palestinians of the occupied West Bank and Gaza to this day.39 Indeed, even a New York Times correspondent in Jerusalem noted in October 1933 that the High Commissioner was given “dictatorial powers.”40

Musa Kazim did not recover from the injuries he sustained during the Jaffa demonstrations. He spent the next five months at home and died on March 26, 1934, at the age of 81. Many blamed British police brutality for his hastened death.41

The passing of the great leader brought with it the end of an era in Palestinian nationalist politics.42 The Arab Executive was dissolved that year, and, with it, the hope of a united Palestinian front against British and Zionist policies. Indeed, the cleavages between the city’s top Palestinian leaders deepened after his death and never recovered. Musa Kazim’s death and the dissolution of the Arab Executive ushered in a new and more revolutionary form of Palestinian resistance that would lead, two years later, to the Great Palestinian Revolt.

Burial and Legacy

Musa Kazim Pasha al-Husseini was survived by three sons: Farid, Sami, and Abd al-Qadir.43 He was buried in al-Madrasa al-Khatuniyya, a madrasa-turned-shrine located in the western corridor of al-Aqsa Mosque between the al-Hadid and al-Qattanin gates. His son Abd al-Qadir, who would become a leading Palestinian military leader and hero of the 1948 War, was also buried in the same shrine beside his father upon his untimely death at the Battle of al-Qastal in April 1948.

Historians summarize Musa Kazim’s legacy as “the undisputed leader of the Palestinian Arabs, the patriarch of Jerusalem’s most prominent notable family, and the highest-ranking ex-Ottoman statesman in Palestine.” His funeral was attended by thousands of Palestinians of all walks of life, going down in history as one of the largest ever to be held in Jerusalem.44

Sources

Ashbee, C. R. Jerusalem 1918–1920, Being the Records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the Period of the British Military Administration. London: Forgotten Books, 2018.

Assi, Seraje. “History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882–1948).” PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2016.

“Desperation in Palestine and the Death of Musa Kazim al-Husayni.” Accessed December 21, 2023.

“Al-Hussaini, Musa Kathim, (Basha) (1853-1934).” Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA). Accessed December 21, 2023.

Huneidi, Sahar. A Broken Trust: Sir Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians: 1920–1925. London: I.B. Tauris, 2001.

Ingrams, Doreen. Palestine Papers, 1917–1922: Seeds of Conflict. New York: G. Braziller, 1973.

Jawhariyyeh, Wasif. The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948. Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2013.

Levy, Joseph. “Dictatorial Rule Set for Palestine; High Commissioner Proclaims Defense Order, although Country Is Orderly.” New York Times, October 31, 1933.

Mattar, Philip. The Mufti of Jerusalem: Al-Hajj Amin al-Husayni and the Palestinian National Movement. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

“Musa Kazim Husseini.” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. Accessed December 21, 2023.

Naser, Mu’tasem, and Randa Abu Hilal. “A Critical Study of the Character and Influence of Musa Kazim al-Husayni during and after the Ottoman Empire.” Science Publishing Group 3, no. 4 (2015): 48–53.

“National Fund: Establishment of Company to Save the Lands of Palestine (in Arabic).” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. Accessed December 21, 2023.

Pappe, Ilan. The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty: The Husaynis, 1700–1948. Oakland: University of California Press, 2011.

“Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929.” HathiTrust. Accessed December 21, 2023.

“Seven Proclamations and Statements relating to the 1929 Palestine Riots.” Kline Books. Accessed December 21, 2023.

Storrs, Ronald. The Memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1937.

“Wadi al-Hawarith: Palestine—Tuesday, June 27, 1933.” [In Arabic.] Palestine Remembered. Accessed December 21, 2023.

“Welcome to Wadi al-Hawarith.” Palestine Remembered. Accessed December 21, 2023.

“World War I and After.” Britannica. Accessed December 21, 2023.

[Profile photo: PASSIA]

Notes

Wasif Jawhariyyeh, The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948 (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2013), 44.

Mu’tasem Naser and Randa Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study of the Character and Influence of Musa Kazim al-Husayni during and after the Ottoman Empire,” Science Publishing Group 3, no. 4 (2015): 48.

“Musa Kazim Husseini,” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, accessed December 21, 2023.

Ilan Pappe, The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty: The Husaynis, 1700–1948 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2011), 111.

“Musa Kazim Husseini.”

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 48.

“Musa Kazim Husseini.”

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 48–49.

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 49.

C. R. Ashbee, Jerusalem 1918–1920, Being the Records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the Period of the British Military Administration (London: Forgotten Books, 2018), v.

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 49.

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 49.

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 49.

Philip Mattar, The Mufti of Jerusalem: Al-Hajj Amin al-Husayni and the Palestinian National Movement (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 17.

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 49.

Pappe, The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty, 199.

Ronald Storrs, The Memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1937).

“World War I and After,” Britannica, accessed December 21, 2023.

Doreen Ingrams, Palestine Papers, 1917–1922: Seeds of Conflict (New York: G. Braziller, 1973), 106.

Seraje Assi, “History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882–1948)” (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2016), 88.

Sahar Huneidi, A Broken Trust: Sir Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians: 1920–1925 (London: I.B. Tauris, 2001), 47.

“Musa Kazim Husseini.”

Mattar, The Mufti, 30–31.

“Al-Hussaini, Musa Kathim, (Basha) (1853-1934),” Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA), accessed December 21, 2023.

Pappe, The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty, 232.

"Seven Proclamations and Statements relating to the 1929 Palestine Riots,” Kline Books, accessed December 21, 2023.

“Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929,” HathiTrust, 158, accessed December 21, 2023.

Mattar, The Mufti, 53.

Mattar, The Mufti, 53.

“Musa Kazim Husseini.”

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 51.

“National Fund: Establishment of Company to Save the Lands of Palestine (in Arabic),” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, accessed December 21, 2023. Translated by the Jerusalem Story Team.

“Welcome to Wadi al-Hawarith,” Palestine Remembered, accessed December 21, 2023.

“Wadi al-Hawarith: Palestine—Tuesday, June 27, 1933” [in Arabic], Palestine Remembered, accessed December 21, 2023. Translated by the Jerusalem Story Team.

“Wadi al-Hawarith: Palestine—Tuesday, June 27, 1933.”

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 51.

“Desperation in Palestine and the Death of Musa Kazim al-Husayni,” accessed December 21, 2023

“Desperation in Palestine.”

“Desperation in Palestine.”

Joseph Levy, “Dictatorial Rule Set for Palestine; High Commissioner Proclaims Defense Order, although Country Is Orderly,” New York Times, October 31, 1933.

“Desperation in Palestine.”

Naser and Abu Hilal, “A Critical Study,” 52.

“Al-Hussaini, Musa Kathim, (Basha) (1853-1934).”

“Desperation in Palestine.”