I don’t like telling you about this next chapter in my life, because it is the beginning of the end for me, the end of living in my homeland among my own people. I know you want to know about what happened, but it’s not easy, Mona dear, to go back to those times.

. . .

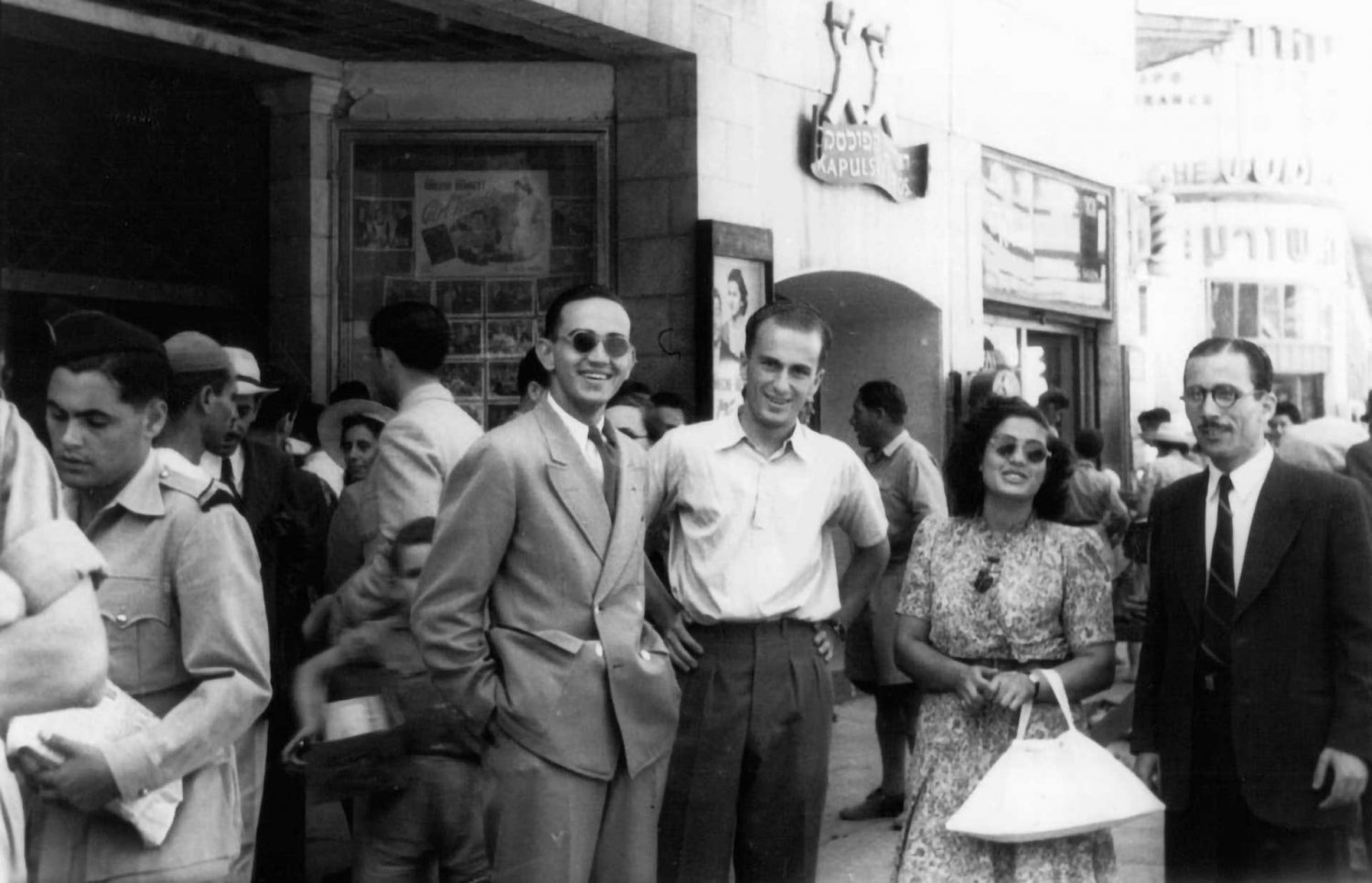

Following the Second World War, tensions in Palestine between Arabs and Jews began to escalate. The official ending of the British Mandate was to take place on May 15, 1948, and both the Arabs and Jews had the same ambitions in mind—to create their own state. It was like we were heading towards a head-on collision. We knew it was going to be a huge disaster, but it was inevitable.

Two years earlier in July 1946, the south wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, where the British Mandate had its military offices, was blown up by the Irgun, a paramilitary, Zionist organization. We were at home when it happened. We heard the loud explosion and ran outside. We saw a huge cloud of smoke hanging over the city. We couldn’t believe what was going on. Then one neighbor called another neighbor, and that’s how we discovered it was the King David. We immediately thought of our friends as the YMCA was just across the street, and we were afraid that some of them might have been hurt, but no one at the YMCA was. About a hundred people perished and many more were injured in the King David bombing. For weeks, the city was in mourning. One of our friends, a woman my age, Hilda, was under the rubble for three days, calling out, “I’m Hilda Azzam. Please help me out.” Sadly, the rescuers were unable to get to her in time, and she perished alone and frightened under tons of limestone. Daily we attended more than one funeral, as every day more bodies were dragged out from the ruins. It was a terrible time, the beginning of the changement, you know, the change of our lives as Palestinians.

. . .

Then on a rainy January night in 1948, we were awakened by a loud noise that shook our whole house. In Qatamon, a couple of miles from our home, the Hotel Semiramis, which also served as the Lorenzo family home, was bombed by the Zionist paramilitary group, the Haganah. The Lorenzos were friends of our family. Sixteen people died, eight from the same family. The next day, as torrential rains came down over Jerusalem, I wanted to attend the funerals, but shootings in the neighborhood prevented me from leaving our home.

During that time, I saw Esther, my Jewish German friend, at one of our choir rehearsals at the YMCA. She asked me, “If your side wins, will you take me in and protect me?” I immediately answered, “But of course, Esther, you don’t need to worry; you’re my friend.” At dinner time that evening, I repeated for my family Esther’s question and my answer. My calm and deliberate father asked me, “And did you ask her the same question if their side wins?”

“No, Papa, I didn’t think to ask her, but I will.”

When I saw Esther again at choir, I asked her, “Esther, and if your side wins, will you hide me and protect me?”

“Oh, no,” she said, looking sheepish, “I couldn’t take the risk of endangering my family.” For a long time, I stared at her in disbelief. What I had believed was a mutual friendship had its limits. That night I came home heartbroken and cynical.

You know, my Darling, even though I was frightened and upset by all these terrible events, I wanted to do something to help my country. I was very courageous, I must say. I worked in two hospitals—the Jerusalem Government Hospital in Musrara, and the Beit Safafa Hospital, on the way to Bethlehem. I spent a lot of time bandaging the wounds of the men shot during the conflicts. We felt these men were giving us the greatest gift—their lives. Every day, a Red Cross truck came to pick me up in front of my house, and when we drove through a Jewish area we had to get down on the floor of the bus for fear of being shot at . . . .