Early Life

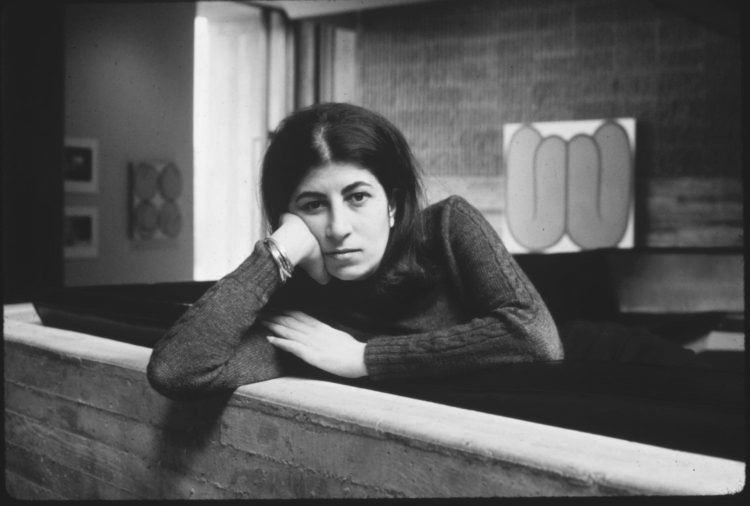

Samia Halaby was born in Jerusalem on December 12, 1936, during the Colonial British Mandate of Palestine, to Assad Saba Halaby and his wife, Foutonie Abdelnour Atallah Halaby. She had two older brothers, Sami and Foud, and a younger sister, Nahida. Samia’s father was a businessman; he founded Jerusalem’s first taxi service in the early 1900s. Her mother was the intellectual of the family, and she bequeathed her love of exploration to the children.

Halaby’s early memories of Jerusalem include vivid images of her grandmother’s house in Jerusalem, with its garden supplying a spectrum of colors, shapes, and subjects that would inspire her future artwork. Her grandmother, who supplied Halaby with stories of the city and its inhabitants, was a fundamental figure in her early life.1 Halaby recalls, “I was born to the sound of these marvelous crowds, to the noise of revolution. My first three years of life were the years of the great Palestinian revolt and general strike from 1936 to 1939.”2

In 1948, with the establishment of Israel, Halaby’s house was robbed and occupied. The family fled to Beirut and remained there until 1951. Assad Halaby, however, returned to Palestine from Lebanon to help fight against the occupation, hoping his family could one day return home. They never did, but instead moved permanently to Cincinnati, Ohio. Halaby describes the effect of both moves on her:

After exile my family took refuge in Beirut. I spent a formative period of my life—between 11 and 14 years of age—in this beautiful city. It had a substantial influence on my aesthetic: the blue sky meeting blue ocean; the beautiful, mature city trees and gardens; the mild sunny weather and architecture in the international style. But in 1951 my family decided to move to Cincinnati. The Midwest felt very earthy and practical. In the Midwest, you can stand at the edge of a road and see a vista of charming barns, hills, and fragments of forest. But I knew that someone owned every part of it. I missed the wildness of the ocean.3

Education and Art Training

When it came to deciding what subjects to pursue in her final two years of high school, Halaby was unsure. Her mother suggested, “You always loved art. Why don’t you study art?”4

Two and a half years after moving to America, Halaby graduated from high school, and then went on to study as an undergraduate at the University of Cincinnati. “I was eager to take advantage of my university education to the fullest. Though I loved the drawing and painting classes, I focused on design. A background in design provided me with more opportunities, professionally, to support myself.”5

She transferred to Michigan State University and earned a bachelor of science degree in design. She then began a graduate program in painting there.

Halaby transferred to Indiana University and graduated in the 1960s with a master of fine arts in painting, after which her artistic career officially began.6

During this time, Halaby admired minimalist styles. The work of Josef Albers informed her sensibilities on color and the relationship between light and contrast. In an interview decades later, Halaby described artists and movements that inspired her:

The revolutionary artists of the past 150 years, Impressionism, Constructivism, Cubism, Futurism, Abstract Expressionism, the Mexican Muralist movement. I respect Malevich, Rivera, Seurat. I also love some of the Renaissance artists. I love Arabic geometric abstraction and calligraphy; they move me deeply.7

Teaching

A 17-year period of teaching followed her graduation. During this time, Halaby traveled all over Italy visiting museums and expanding upon her training through exposure to art beyond academia. She felt the need to rid herself of academic influences on, and preconceived notions about, art, especially its abstract rendition. For Halaby, abstract art was not a form monopolized by a cultured elite, but rather it belonged to the working class.8 Halaby stated in an interview:

The state of art follows the state of society, which since the mid-19th century has experienced the growth of class struggle. Throughout this period, advanced pictorial art has been created by those who support working class revolution, whether with deep lifelong understanding or for specific periods of revolutionary zeal. The remainder of artists, the vast majority, range in shades of loyalty to the bourgeoisie or to being unaware. Political intuition and their life’s situation have enlightened them in different ways.9

These ideas began to manifest just as Halaby took up teaching at the Kansas City Art Institute.10 Now in an academic position herself, she encouraged her students to explore art through a new lens, one that seriously considered how we perceived the world.

Between 1972 and 1982, Halaby taught at the Yale School of Art; she was the first woman in the institution’s history to hold the rank of associate professor. There she developed an undergraduate studio art program that became fundamental to training young artists in the Midwest.11

Despite her contributions to the art program and after she taught on a tenure track for 10 years, Yale denied Halaby tenure and fired her. Many students supported her against what was possibly a sexist (and certainly an unfair) decision. Indeed, Yale’s tendency to let go of female faculty was becoming a pattern, reinforcing the prestigious university’s reputation of not employing women as full-time instructors.12 Halaby’s presence during her 10-year employment was merely a gesture to dispel the reputation, but when it came time for her to receive tenure, she was dismissed. Some students worked with Halaby to organize an exhibition in New York titled, “On Trial: Yale School of Art.”13

In the early 1980s, Halaby stopped teaching and devoted herself entirely to painting.

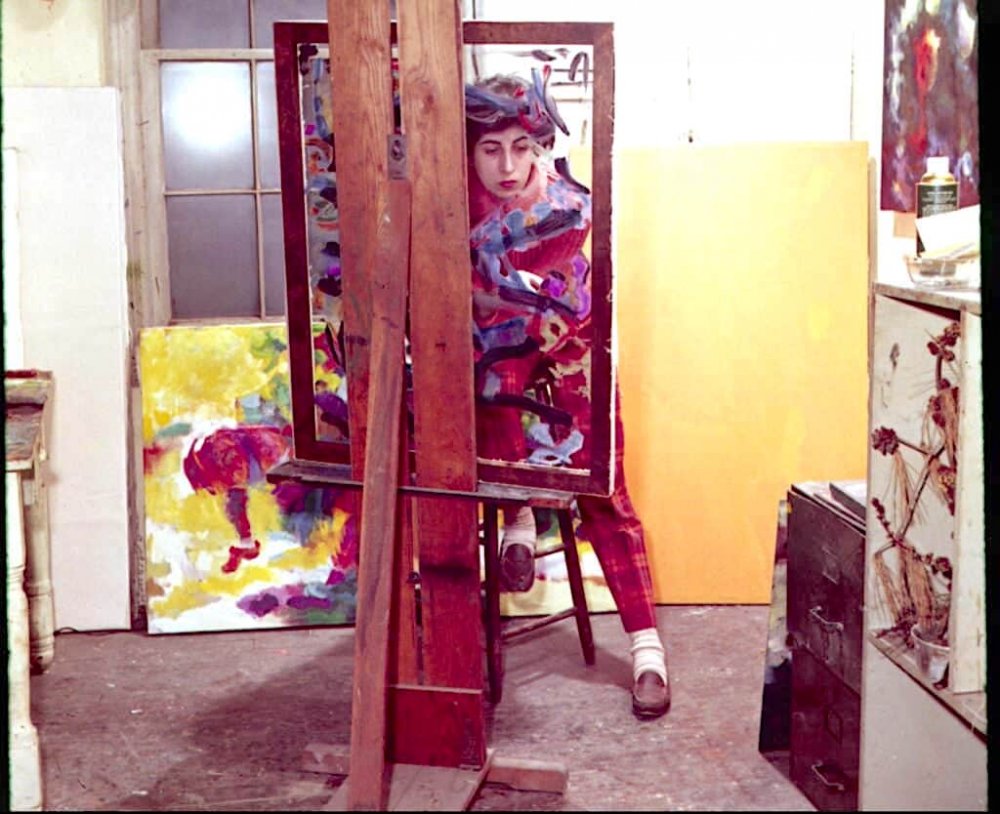

Exploring Visual Language

Halaby prefers not to call her work “art.” She says: “I think the word ‘art’ is difficult because it covers so much. I prefer to discuss my own area of expertise, pictures. Pictures in numerous media serve mankind in applications such as language, entertainment, illustration, research and more. It also has a leading edge of creative research. This is where I attempt to be with my artwork.”14

There was a decisive shift in Halaby’s attitude and style in 1965, at which point she developed new ideas about how to recreate and interpret what she observed. She writes, “I began to feel that I must make a clean, new beginning and erase my teachers and my past out of my thoughts.” This coincided with her teaching at Kansas City Art, and she used her new ideas to propel an experimental program for first-year art students.

Since the 1970s, Halaby has lived and worked in New York. When she first moved to the Big Apple, she did not find a warm reception; she was an Arab and a woman (and an immigrant), and her work was rejected at first. “Only a few doors were open to me, and mostly in the Midwest in small flirtations with museums. I used to brag that I have more museum credits but no New York gallery ones.”15 Indeed, she found the art scene in New York to be racial, competitive, and not at all collaborative.

Halaby has produced over 3,000 works, ranging from paintings, digital media, sketches, sculpture, and other artistic mediums. Her main endeavor has been to give form to intangible realities, such as time. This exploration led Halaby on a long journey of experimentation with different artistic mediums and styles.

Halaby’s work was informed by both the Arab world and the West. From the former, she drew inspiration from the great mosques she visited, including al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. From the West, she was exposed to Abstract Expressionism.16

Her characteristic use of geometric combinations was in fact a stylistic decision Halaby arrived at when it came to choosing between focusing on human portraits or nonhuman subjects and intangible concepts. To hone her skills, Halaby relied on geometry books, including several that explored how to make three-dimensional pipe fittings out of flat shapes. This fed into Halaby’s Helixes and Cycloids series, after which she began working on Diagonal Flight—a series that focuses on diagonal horizons. Her inspiration was a group of children pretending to be airplanes, running with their arms outstretched and imitating engine noises.

Another feature of Halaby’s artwork is its abstract style. She draws her inspiration from nature and builds upon features of Arabic art and architecture. This is most noticeable in her paintings featuring Palestine’s natural landscape. Halaby rejected a commonly held idea among her contemporaries which maintains that Islamic art was essentially random decoration, devoid of meaning. Halaby argues that it is much more than that:

Arab art is decidedly misunderstood by most Arab historians who mimic the misunderstanding of European and US historians. Very few take an international and historical view and are able to see the relationship of contemporary Arab art and the history of Arab art. . . . Most historians are unable to understand why medieval Arabic abstraction is not decoration and that its value is as great as any European painting. These are basically problems of colonial inferiority complexes and not realities in the history of Arabic art, historic or contemporary.17

Alongside her focus on Palestinian visual culture, another part of Halaby’s work focuses on capturing daily experiences in New York City. She converted her own loft in New York into an exhibit-like space where she hosted poetry evenings and showcased paintings. The cultural evenings that took place there soon boasted of a multiracial and multicultural group of artists sharing their work.18

Halaby’s style is still more diverse than works of abstraction. She easily moves between geometric and free-form paintings.

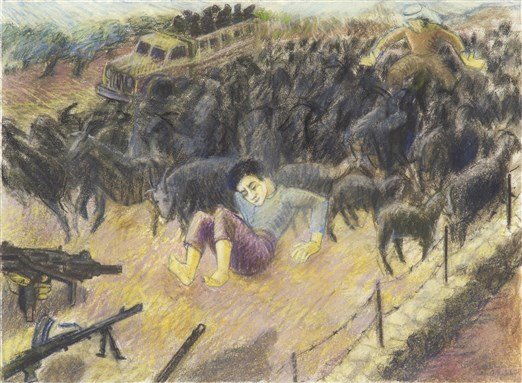

Some of her pieces that act as political commentary draw on figurative drawing. This includes, for example, her Kafr Qasim series, which depicts the 1965 Kafr Qasim massacre, when 49 Palestinian civilians were killed by Israel for violating a curfew that they were unaware of.19 Halaby described the project:

I was led to it by a daughter of Kafr Qasem sometime during the mid-1990s. Her name was Aishe Amer and she was determined that every Palestinian artist should do at least one painting about the massacre. She took me there and hosted, introduced, and guided me and would not let go until she connected me to her friends there. As time went by, the compelling power of the story led me to create far more than one painting on the subject. I determined that the drawings would not be an exploration of painting but a performance of my knowledge and skill in the service of documentation.20

Other politically driven pieces include posters and banners advocating an end to Israeli occupation.

Halaby’s work was driven by the need to understand how the eye operated—namely, how vision rested on the surface of an object then reached beyond to a farther background—and replicating that in her work. This became her constant challenge when she explored artistic subjects. Exploring reality in such a way, Halaby believed, in turn influenced the very way we saw, thought, and interacted with the world.21

In the 2000s, her painting style moved away from typical geometric shapes and relied more on smooth vibrant brushstrokes, representing how vision settled on different objects.

Dome of the Rock

A trip to Jerusalem, Damascus, and Istanbul in 1966 inspired Halaby’s series Dome of the Rock. She depicted the famous monument using symmetrical diagonal lines surrounded by diamonds. The patterns Halaby saw in the mosques became a permanent feature of all her work.

Art and Political Activism

Halaby’s political activism sprouted when she was a child, when her father and other men would gather in her house to plan how they would defend Palestine against the occupying Israeli force. These meetings had a profound impact on her:

Everyone shared opinions and expressions of pain and loss. Anytime any discussion of politics took place thereafter brought me pain. Years later I recovered and realised that deep in my feelings those were meetings of men wailing, and with the realisation, the pain receded replaced by understanding.22

On her trip to Jerusalem, which took place during her hiatus from painting, Halaby met sculptor Mona Saudi. Saudi served as the director of the Plastic Arts Section of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. She offered Halaby a place in an exhibition at the Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo. The exhibition’s theme was life portrayed while under attack and oppression.

Jerusalem was the subject of her 2014 series, Jerusalem, My Home. For this project, Halaby once more returned to her city and visited what to her was its most iconic symbol: the Dome of the Rock. The pictures she created representing her home were the product of the past engraved in her mind. She says:

In my memory there is a shape like a candle flame, luminescent but cooler in color and warm to the touch. This is the very shape which visually forms in my mind as the aggregate of my memories of Jerusalem. It is made up of grandmothers, visiting relatives, wonderment at fountains in gardens of fruits and blossoms, the turn of a narrow street, the old city walls and shops, the calm and peace of its people, the stone arches and domes of an old bakery, the grand uncle in his shoe repair shop, the vegetable seller on his donkey, and the modern burgeoning new neighborhoods with beeping cars and bustling shops. I remember the persuasion that we lived here in our Quds at the wellsprings of culture.23

After 1995, Halaby visited Palestine at least twice a year. She worked with Birzeit University, supported local Palestinian artists, and launched several projects. In 2002, her month-long exhibition Williamsburg Bridges Palestine took place at the Williamsburg Art & Historical Center and presented the work of 50 Palestinian artists. Halaby personally traveled to several cities in Palestine collecting the pieces for the show.24 The exhibit also included Palestinian poets, writers, and comedians.25

In 2019, Halaby founded the Samia A. Halaby Foundation, an organization that works with women and children of a working-class background in Palestine, offering them classes and training in various art forms, such as painting and filmmaking, with the aim of equipping its participants with a means of earning a livelihood and encouraging their creativity.26

Exhibits

While Jerusalem (and Palestine generally) have occupied an important place in her work and intellectual concerns, Halaby resists being placed in a “specific niche.” “I am indeed Palestinian and Arab, but my art and my thinking is international.”27

Throughout a career that has spanned more than six decades, Halaby has become a world-renowned artist who moves easily between the Western and Arab art worlds. Her work has been showcased in galleries and museums throughout Europe, North and South America, and Asia: the Guggenheim in New York and Abu Dhabi, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Institut du Monde Arabe, and Birzeit University. She is represented by Ayyam Gallery (Beirut and Dubai).

The first American retrospective of her work, which took three years to organize, was scheduled to open at her alma mater, Indiana University, at the university’s Eskenazi Museum of Art, on February 10, 2024.

In early January, Halaby received a two-line note from the director of the museum abruptly canceling the show without explanation. The Provost claimed that the show would be a “lightning rod” and cause trouble because of Israel’s war on Gaza launched October 7, 2023. The exhibition was also accused of carrying an anti-Semitic undertone.28 Halaby responds:

I think this idea that they’re so terrorized or frightened by me being a lightning rod . . . I think this idea of a lightning rod for trouble is their imagination, their invention. It’s just a propaganda—you, know, invention . . . They’re so frightened.29

For Halaby, who was raised in the Midwest, the cancelation was a rude awakening. “I thought I had found a little bit of something I could call my home in Indiana,” she later said, “and it turned out to be totally false.”30

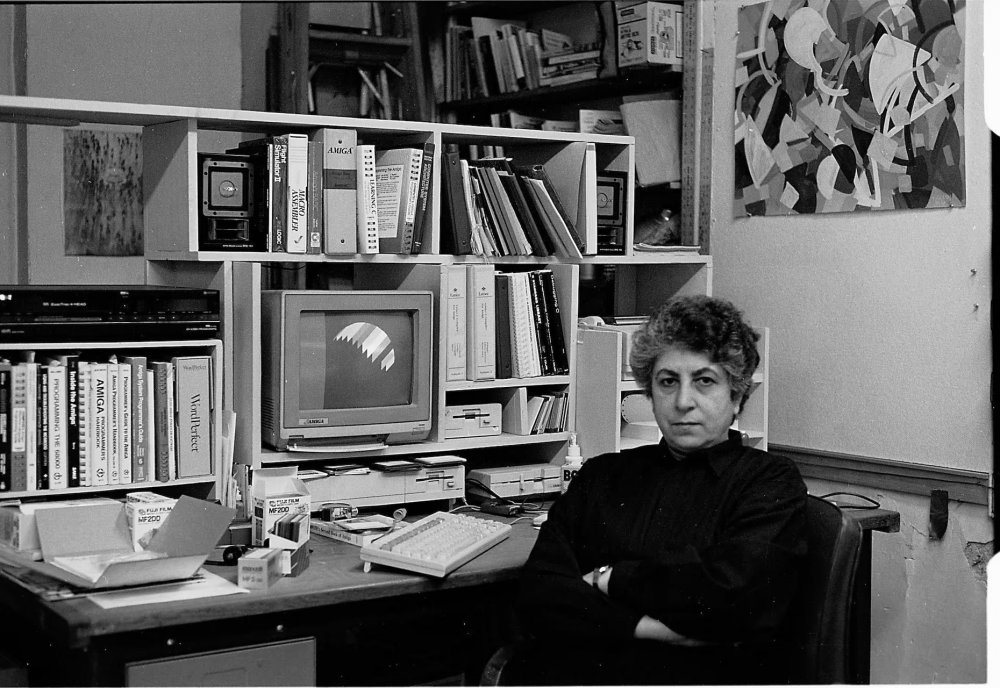

A Life Exploring the World through Art

After retiring from teaching in the 1980s, Halaby taught herself programming and delved into electronic art. She created a program that documented the process of live painting and formed the “Kinetic Painting Group.” The images this group produced brought together geometric shapes with motion and sound to create “kinetic paintings.”

Halaby has spent her life creating a visual language that expresses the way we look at the world. In so doing, she has produced pioneering artistic work that explored time, sound, and motion. Her creative investigations fueled a lifelong career that sought to use principles of abstraction to answer the question: How can reality be represented through form?

Selected Works

“Reflecting Reality in Abstract Painting.” Leonardo 20, no. 3 (1987): 241–46.

“On Politics and Art.” Arab Studies Quarterly 11, no. 2/3 (1989): 155–65.

“The Landscape of Palestine in Arabic Art.” In The Landscape of Palestine: Equivocal Poetry, edited by Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Roger Heacock, and Khaled Nashef, 175–91. Birzeit: Birzeit University Publications, 1999.

Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century. New York: H.T.T.B. Publications, 2001.

Samia Halaby: Five Decades of Painting and Innovation. London: Booth-Clibbon Editions, 2014.

Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre. Amsterdam: Schilt Publishing, 2017.

Growing Shapes: Aesthetic Insights of an Abstract Painter. Wooster, OH: Palestine Books in collaboration with Ayyam Gallery, 2016.

“The Political Basis of Abstraction in the 20th Century as Explored by a Painter.” Manazir Journal 1 (2019): 77–89.

Sources

“Biography: Samia A. Halaby, 2003.” Art.net. Accessed March 28, 2024.

Ghantous, Tamara. “Spirit Unbound: The Journey of Female Arab Artists through Time – pt.1.” February 5, 2024.

Goodman, Jonathan. “Interview with Artist Samia Halaby.” ArteFuse, February 21, 2018.

Halaby, Samia, and Maymanah Farhat. “Reflections: Samia Halaby.” Artezine (Winter 2007).

Mason, John. “Arab American Pathbreaker – Samia A. Halaby.” Arab America, February 7, 2024.

Morelli, Naima. “Samia Halaby: Radical Optimism in Art and Political Commitment for Palestine.” The New Arab, January 19, 2024.

“Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby Slams Indiana University for Canceling Exhibit over Her Support for Gaza.” Democracy Now, January 18, 2024.

“Samia Halaby.” Ayyam Gallery. Accessed March 28, 2024.

“Samia Halaby.” Los Angeles Review of Books. Accessed March 28, 2024.

Samia Halaby Foundation. Accessed March 28, 2024.

Schrader, Adam. “Indiana University Has Canceled a Retrospective on Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby.” Artnet, January 11, 2024.

Small, Zachary. “Indiana University Cancels Major Exhibition of Palestinian Artist.” New York Times, January 11, 2024.

Wolfe, Shira. “Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Samia Halaby.” Artland Magazine, December 18, 2020.

[Profile photo: Courtesy of Samia Halaby (via The Cut)]

Notes

Shira Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Samia Halaby,” Artland Magazine, December 18, 2020.

“Biography: Samia A. Halaby, 2003,” art.net, accessed March 28, 2024.

Jonathan Goodman, “Interview with Artist Samia Halaby,” ArteFuse, February 21, 2018.

“Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby Slams Indiana University for Canceling Exhibit over Her Support for Gaza,” Democracy Now, January 18, 2024.

Goodman, “Interview.”

“Samia Halaby,” Los Angeles Review of Books, accessed March 28, 2024.

Samia Halaby and Maymanah Farhat, “Reflections: Samia Halaby,” Artezine (Winter 2007).

Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series.”

Halaby and Farhat, “Reflections.”

Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series.”

“Samia Halaby,” Ayyam Gallery, accessed March 28, 2024.

Tamara Ghantous, “Spirit Unbound: The Journey of Female Arab Artists through Time – pt.1,” February 5, 2024.

“Biography.”

Halaby and Farhat, “Reflections.”

Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series.”

Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series.”

Halaby and Farhat, “Reflections.”

“Biography.”

Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series.”

Wolfe, “Lost (and Found) Artist Series.”

“Samia Halaby,” Los Angeles Review of Books.

Naima Morelli, “Samia Halaby: Radical Optimism in Art and Political Commitment for Palestine,” The New Arab, January 19, 2024.

“Biography.”

“Biography.”

For a list of participants, see “Williamsburg Bridges Palestine: The Face of Palestinian Humanity through Art & Culture,” Al-Jisser, the Arab American Media Center, and the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association, November 2–24, 2002.

Samia Halaby Foundation, accessed March 28, 2024.

Goodman, “Interview.”

Adam Schrader, “Indiana University Has Canceled a Retrospective on Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby,” Artnet, January 11, 2024.

John Mason, “Arab American Pathbreaker – Samia A. Halaby,” Arab America, February 7, 2024.

Zachary Small, “Indiana University Cancels Major Exhibition of Palestinian Artist,” New York Times, January 11, 2024.