Mahmoud Shukair (b. 1941 in Jerusalem) is an award-winning writer, especially known for his short stories and novels for young adults and children. He is the author of more than 70 books, 6 television series, and 4 plays. His writings have been translated into more than 10 languages.

Childhood and Education

Shukair was born in Jabal al-Mukabbir, a Palestinian neighborhood on the southeastern edge of Jerusalem, in 1941. He spent much of his childhood reading avidly; literature fascinated him, and he read well beyond what was required by the school curriculum. As a child, his father took him to the Old City every Friday to pray at al-Aqsa Mosque, and he came to know the area very well.1 Ever since, he has been mesmerized by Jerusalem. Later it would feature prominently in his novels.

As with many voracious readers, Shukair wanted to become a writer, and as is the case with many aspiring writers, his initial submissions were frequently rejected. However, this did not deter him, and he kept submitting essays to journals and magazines.

Finally, his first story was published in 1961 by al-Ufuq al-Jadid (The New Horizon). Shukair had been quite intrigued by that new magazine, which had just been launched that year in East Jerusalem and offered fresh content. Shukair’s first published story dealt with the Israeli attack on his neighborhood in Jabal al-Mukabbir in 1948. The Nakba affected him profoundly; in an interview decades later, he said that he has been living the Palestinian tragedy ever since 1948.2

And with that first publication, a writer was born. The 20-year-old Shukair went on to publish extensively for more than six decades.

Shukair received a master’s degree in philosophy and sociology in 1965 from Damascus University. He worked as a teacher and a journalist. He also edited various cultural magazines and newspapers.

Imprisonment and Deportation

Shukair’s writings were fundamentally inspired by his life and experiences in Jerusalem, which meant that he also wrote about political events. Not surprisingly, he roused the displeasure of the Israeli occupation authorities.

Shukair notes in his writings and interviews that Israel could not handle the accurate depiction of the brutal reality it created in Palestine. He often organized and participated in strikes and demonstrations in Jerusalem against the Israeli occupation, and in 1969, the Israeli authorities jailed him for his political activism and held him in administrative detention for 10 months. In 1972, he was put under house arrest for a year, but that did not stop his activism: In October 1973, the Israeli forces banged on the door of his family house in Jabal al-Mukabbir but did not find him at home. He managed to remain in hiding for two months. They eventually captured him, and he was jailed for another 10 months.

Shukair sometimes wrote political commentary under the aliases Fares Abu Bakr and Ribhi Hafez to avoid retaliation by the Israeli newspaper censors.

Shukair joined the Palestinian Communist Party (later the Palestinian People’s Party) in 1965, and in 1975, he was deported for his political activism. He spent almost two decades outside of his beloved Jerusalem, but the city continued to be a main character in his writings. He lived in Beirut for eight months, then moved to Amman and stayed there until 1987, when he was invited to the Palestinian Writers’ Conference in Algiers. From there, he went to Prague and stayed for the next three years before returning to Amman.

In 1993 Shukair’s exile ended. The Oslo Accords were signed, and he was among the 30 deportees who were allowed to return to Palestine.

Author and Editor

During his years in Amman, Shukair had prominent roles in the literary field. He was vice president of the Jordanian Writers’ Society and a member of its board for 10 years (1977–87). He was also a member of the General Union for Palestinian Writers and Journalists (1987–2004); the Palestinian National Council (PNC) (1988–96); and the Palestinian Community Party (1976–98).

After he returned to Jerusalem, Shukair became editor in chief of al-Tali‘a (The Vanguard) weekly cultural magazine (1994–96). Between 1997 and 2000, he was editor in chief of the Palestinian Ministry of Culture’s periodical Dafatar Thaqafiyya (Cultural Files). He also edited the cultural issues of the journal Sawt al-Watan (Sound of the Homeland), published in Ramallah, from 1997 to 2002.

Despite his noteworthy career in journalism, Shukair would be most known for his literary output. By 2022, Shukair had published a total of 78 books, including short story collections (among them, The Bread of Others, 1975; The Palestinian Boy, 1977; Rites for the Wretched Woman, 1986; and The Silence of Windows, 1995), novels, biographies, travelogues, and literature for young adults and children. In addition to the books he wrote, he cowrote and coedited eight other books (with different authors). He also wrote four plays and scripts for six Arabic-language television series.

Writing Style

Shukair is known for his young adult and children’s stories. His short stories have been published in journals and anthologies worldwide. His work has been translated to more than 10 languages, including English, French, German, Spanish, Korean, Mongolian, Czech, and Chinese.

At the beginning of his writing career, his writing focused on the Palestinian tragedy and the interpersonal relationships amid exile and Israeli occupation. In later years, however, his works took on an ironic tone.

One of Shukair’s popular stories is “Me, My Friend, and the Donkey” (2016), a humorous detective adventure for teenagers. The story, set in Jerusalem, is based on his and his best friend’s actual search for a lost donkey when they were children. He also wrote stories with female main characters in fantasy tales, such as “Jumana and I” and “Mariam’s Talk.” He often had discussions, both in person as well as online, with children about his stories.

Shukair also wrote autobiographical and nonfiction works. The Mirror of Absence: Diaries of Sadness and Politics (2007) reflects on the history of the Palestinian Communist Party.

Shukair exposes the surreal moments in the mundane and tells complex stories in a simple manner. He relays the poetic details of everyday life; the details are crucial to him because he believes that Israel and its supporters try to deny the existence of Palestinians as a distinct nation. The Palestinian characters in his novels are depicted in ways that show how hollow such efforts are.

Jerusalem as a Story Character

In a conversation with Lama Amr during the Palestine Writes Literature Festival at the end of 2020, Shukair explained the importance of details as they pertain to his memory of Jerusalem. In some of his books, he notes:

I wrote about the windows, the doors, the neighborhoods, the alleyways, and the souqs . . . I wrote about all of Jerusalem and documented it. The character of Jerusalem stands out in some of the stories I wrote, and it often took a heroic role in them.3

In his view, Jerusalem has been under the threat of demolition, destruction, robbery, and erasure. Documenting it through literature becomes a form of resistance.

“The image that I had drawn [of Jerusalem] in my childhood memory never escaped me,” he says in an interview from 2019, and adds that he is still haunted by the memories of the Nakba of 1948 and the Naksa of 1967.4

He notes how East Jerusalem changed massively after the 1967 War, but the Palestinian presence nevertheless sustained itself. He notes the sense of resistance and revival of the Palestinian people, yet he also openly criticizes the traditional mindset and rigid stances of the people, which at one point had been relatively enlightened. In his view, the Israeli occupation prevented society from modernizing; the people of Palestine were fearful and held on to their traditions because they were anxious about the loss of their land and culture.

Shukair wrote about his jail experience, encouraged to do so by Mahmoud Darwish. Darwish, editor of al-Carmel, invited a few Palestinian returnee writers to recall their memory of places during their exile, and Shukair wrote about Jerusalem. For anyone experiencing exile and displacement, he observed, a sense of place was critically important. His 2018 book Jerusalem Stands Alone bears this dedication: “To Jerusalem, the city that taught me to love.” In the opening pages, he writes:

In the morning I walk to the markets surrounded by the city’s history, ghostly layers of people from past eras, men of different ages and women of different times. The living women are careful to avoid physical contact, which the overcrowding all but invites. In this city, soldiers are everywhere.

I return from my usual walk to sit in the Damascus Gate Café on the terrace overlooking the market. The waiter is busy serving other customers. Is he the same waiter from before or someone who looks like him? (Stories of doppelgangers are spreading throughout the city.)

I contemplate the yellowing rocks of the Walls of Jerusalem and the windows of the houses spread out before me. Some are closed, others open, and I imagine the stories and secrets hidden within. I drink tea and watch a thin blonde foreigner slowly sipping her coffee, attentively turning the pages of her book while I spread my papers out in front of me. The woman leaves. (Maybe she’s from a different time?)

I remain at the café until evening but the windows of the houses refuse to speak.5

Equality of Women

In his novels, Shukair calls for women’s equality; in his view, political equality would be impossible in a society that denies women justice, dignity, and an equal footing with men. His renowned 2016 novel, Praise for the Women of the Family, addresses this theme.

The book is a family saga about an aging Bedouin man who hopes that the youngest of his 18 sons, Muhammad al-Asghar (age 42 years), would take on leadership of the family and hold the clan together. However, al-Asghar is torn between old customs and new choices; he is married to an open-minded childless divorcee and aspires to be a writer. The women’s gossip and judgment that al-Asghar hears around him, particularly from his mother (his father’s sixth wife), express the reality for women in the clan, and he becomes both aware of and exasperated with social treatment of women. The book also describes how political circumstances such as the Nakba weaken Palestinian society.

Praise for the Women of the Family is actually the second part of a trilogy. The first part captures the years 1900–1940; the second delves into World War II through 1948; and the third carries on after the Nakba and into the early 1980s. The women in these chapters are largely symbolic, as they represent different types of women in Palestinian society (such as the divorced, the mother of a martyr, the traditional woman, the modern woman).

Shukair claims he wrote Praise for the Women of the Family to confront patriarchal attitudes. Although he was criticized for including women’s gossip, he in fact looks at women’s gossip as knowledge-feeding and sees it as a rebellious act through which women express their exasperation with society.

Honors and Achievements

Shukair established himself as a prominent writer and was celebrated for his creative talents. He received a prize for best short story writer from the Association of Jordanian Writers in 1991. In 2005, the Palestinian Ministry of Culture honored him;through a special workshop highlighting his works during the Sixth Palestinian International Book Fair, held in Ramallah in 2005. He received the Mahmoud Darwish Prize for “Freedom of Expression” Creativity in 2011.

His novel Praise for the Women of the Family was shortlisted in 2016 for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (The Arab Booker Prize), the most prestigious and important literary prize in the Arab world. It also won the International Prize for Arab Fiction in that same year. It was translated into English by British scholar and literary translator Paul Starkey.

His short story “Me, My Friend, and the Donkey” was selected by the International Board of Books for Young People as one of the top 100 children’s novels from around the world.

Shukair participated in several international conferences for writers, including the Arab Writers’ Conference in Tripoli (1977 and 1988). He also headed the Palestinian delegation of writers to the Arab Writers’ Conference in Amman (1992) and attended the one in Damascus in 1998. In Amman, he attended various conferences including the Children’s Writing Conference in 1999.

He was invited to various conferences outside the Arab world. In Norway, he attended numerous events including the cultural festivals in Molde (1997) and Stavanger (2002 and 2003). He took part at the International Writers’ Program in Iowa, US (1998), as well as at the Hong Kong Baptist University (2005), and the Manchester Culture Festival (2006).

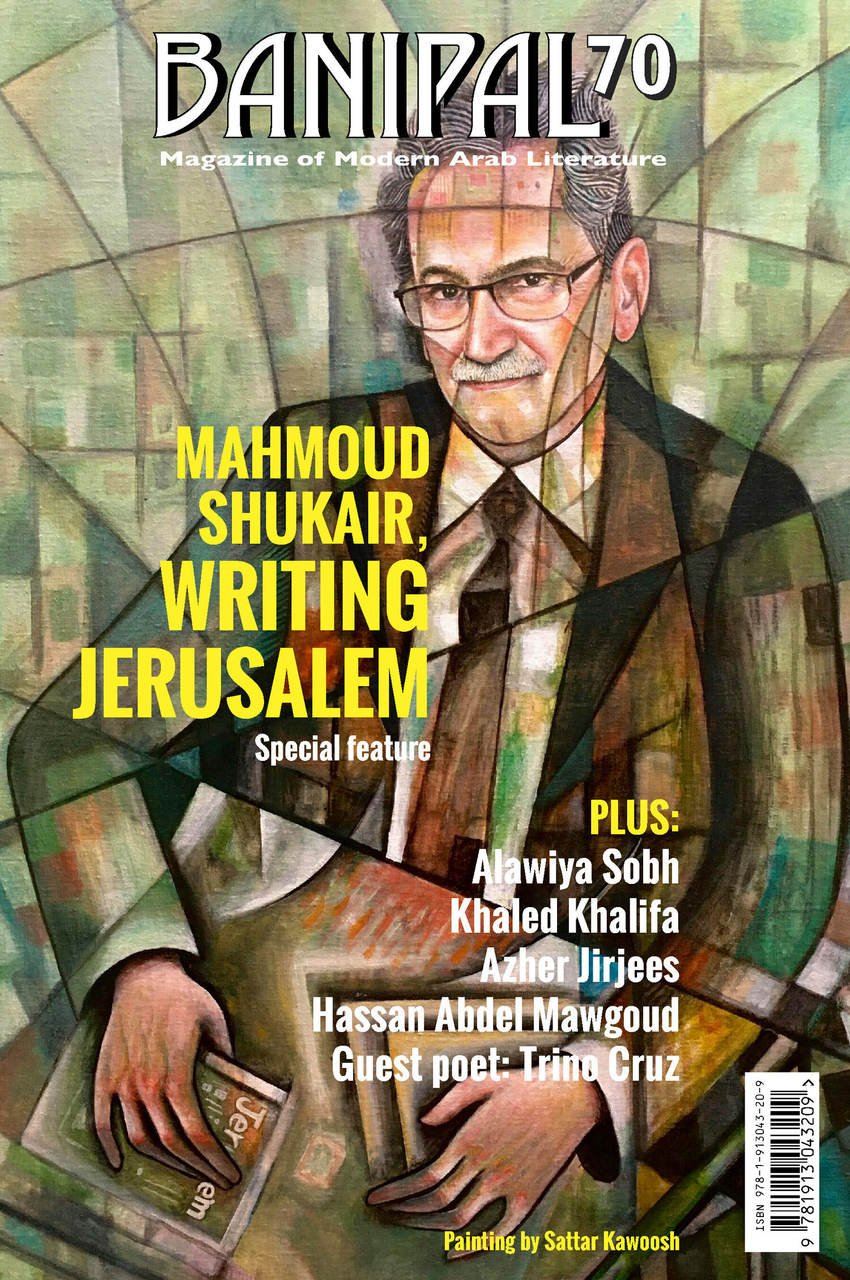

Shukair was honored on the special 70th issue of Banipal: Magazine of Modern Arab Literature in the spring 2021 issue. His portrait, drawn by Iraqi artist Sattar Kawoosh, graced the cover.

Translated Short Stories and Novels

A selected list of his literary output over the years includes: “Other People’s Bread” (1975), “The Palestinian Boy” (1977), “Rituals of a Wretched Woman” (1986), “The Windows’ Silence” (1991), “Another Shadow for the City” (1998), “A Rapid Passing” (2002), “Shakira’s Picture” (2003), “My Cousin Condoleezza” (2004), “A Small Courtyard for Evening Sorrows” (2004), “Mordechai’s Mustache and His Wife’s Cats” (2006), “Slight Possibilities” (2006), “Mirrors of Absence” (2007), “Windows of Jerusalem” (2008), “Jerusalem Stands Alone” (2010), “City of Loss and Desire” (2011), The Family Mare (2013), Praise for the Women of the Family (2015), Roofs of Desire (2017), Shadow of the Family (2019), and Those Places: An Autobiography (2020).

Personal Life

In 1960, Shukair married his wife, Na‘ima, with whom he shares 2 daughters, 3 sons, and 15 grandchildren. He currently resides in Jabal al-Mukkabir in East Jerusalem.

Sources

Berlin International Festival. “Mahmoud Shukair.” Accessed October 15, 2022.

International Prize for Arabic Fiction. “Mahmoud Shukair.”

Jabbour, Eman. “Mahmoud Shukair . . . 60 Years of Giving in the Palestinian Cultural Field.” Alghad. November 28, 2019.

Kateb Maktub. “Mahmoud Shukair.” [In Arabic.] Accessed October 13, 2022.

“Mahmoud Shukair.” Banipal: Magazine of Modern Arab Literature. 2021.

Palestine Writes’ Literature Festival. “‘Praise for the Women of the Family’ by Mahmoud Shuqeir.” [In Arabic.] YouTube. December 28, 2020.

Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs. “Shuqeir, Mahmoud (1941 –).” Accessed October 11, 2022.

Word Without Borders. “Mahmoud Shukair.” Accessed October 11, 2022.

Zafar, Anam. “An Excerpt from Mahmoud Shukair’s ‘Me, My Friend, and the Donkey.’” Arablit and Arablit Quarterly. March 22, 2021.

[Profile photo: PASSIA, Item 716]

Notes

Eman Jabbour, “Mahmoud Shukair . . . 60 Years of Giving in the Palestinian Cultural Field,” Alghad, November 28, 2019.

Jabbour, “Mahmoud Shukair.”

Palestine Writers’ Literature Festival, “‘Praise for the Women of the Family’ by Mahmoud Shuqeir” [in Arabic], YouTube, December 28, 2020.

Jabbour, “Mahmoud Shukair.”

Mahmoud Shukair, Jerusalem Stands Alone, trans. Nicole Fares (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2018), 1.