Fatima Budeiri (b. 1923 in Jerusalem) began her career as an Arabic teacher and then moved into journalism. She was among the first professional women to work in the media in the Arab world and the first Palestinian woman radio broadcaster.

Education and Teaching Career

Fatima Budeiri was born in 1923 in Jerusalem to an esteemed Palestinian family with a long history in the city. Her father was Sheikh Musa Budeiri, a judge in the sharia (Islamic law) court and head of the Palestine Scholars’ Council.

Budeiri grew up in Jerusalem and graduated from the Schmidt’s Girls College with a high school diploma. She pursued her studies at the Teachers’ College in Jerusalem and graduated with a degree in education in 1941. She taught Arabic language for about five years in various Palestinian towns, including Bethlehem and Ramallah.

Budeiri was known for her eloquence in the Arabic language, which she credits to her father who had encouraged his children to read the Quran for half an hour every day.

Career Move

In 1946, Budeiri made the transition from education to media work. She applied to work as a broadcaster and producer at Huna al-Quds (This Is Jerusalem/Jerusalem Calling). This was the first radio station in Palestine, and it was launched in Jerusalem in March 1936 through the Palestine Broadcasting Service, which was established by the British Mandate authorities. It was the second Arab radio station after Cairo, which had been established in mid-1934.1

Thanks to her language skills, she was hired on the spot.

Success and Marriage

Budeiri soon became a well-recognized voice at Huna al-Quds, where she presented an array of cultural programs and supervised the women’s and children’s programs. Unlike the news division, which was strictly supervised by the mandate authorities, Palestinian staff were given authority over the art and cultural programs. (The 2011 documentary about the Jerusalem station Jerusalem Calling by Raed Duzdar draws on the station’s archival footage to convey the richness of the cultural life in Jerusalem and Palestine as a whole prior to the Nakba.2) The staff were required to uphold a high standard of Arabic in their programs.3 Budeiri also did news bulletins, which she not only presented but also prepared and translated.

She worked alongside Issam Hammad, an established journalist, writer, poet, and fellow broadcaster. Hammad wrote her love poems. The two married in 1948 and eventually had two sons.

Breaking Traditional Gender Roles—and Paying the Price

Budeiri was breaking boundaries for daringly going into the professional field at a time when it was not socially acceptable for women to do so, particularly in the public domain. Her career move from teaching to broadcasting gave her a larger public role. Her voice was widely broadcast: She presented programs and news bulletins, the only female broadcaster to do so. She also acted in radio dramas—another daring career move.

Criticism of Budeiri’s career path was harsh; she confessed in an interview years later that she believed her own mother was not proud of her work.4 Although Budeiri’s father was socially condemned for allowing his daughter to proceed in this field, the sheikh had not objected to his daughter’s career path. In an interview, Budeiri disclosed that her father, her brothers (one was a doctor and the other an engineer), and her husband had no objections to her career in broadcasting; her husband actually encouraged her all the way. However, social and family circles made things difficult for her. She and her husband received threats about her career, particularly when she first started her work in radio.5 This may sound bizarre today, but at the time, there were only two other female professional Arab broadcasters, both in Egypt: Safiyya al-Muhandis and Tamadur Tawfiq.

Turbulent Times

Huna al-Quds, the pioneer radio station, ceased transmission from Jerusalem after the 1948 War. The radio station was moved to Ramallah, which was ruled by Jordan, and then to Amman, where it became the Jordanian radio station.

In later years, talking about the 1948 War would bring back “bitter memories . . . The entire country was on the verge of getting completely emptied.”6 Budeiri and her husband temporarily moved to Damascus, and together they established a Syrian radio station in 1950.

Two years later, in 1952, they went back to Ramallah, where she worked at the same radio station (through the Jordanian Broadcasting Service) until 1957.7 During this period, she also worked as an educator.

In 1957, Budeiri and her husband left Ramallah and went back to Syria. One year later, they went to what was then East Berlin, and the two worked for the German Democratic Radio (Radio Berlin Arab and East German Radio) from 1958 until 1965.

The couple went back to Ramallah after 1965, and Budeiri once again worked as an Arabic language teacher. She also became the curator of the UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) Library. Two years later, they relocated to Jordan, and Budeiri worked at the University of Jordan Library in the classification department (1978–83). She also worked at the Jordanian House for Culture and Media in Amman until her death.

Distinctive and Eloquent Voice

Budeiri’s radio voice became well-known in Palestine and the region. Even those who criticized her for working in broadcasting and breaking traditions expressed a grudging admiration: They acknowledged her successful career, the potency of her parlance, and the persuasive way in which she delivered her programs.

In addition to her proficiency in Arabic, Budeiri was also fluent in English and German. She participated in several Arab and international conferences in her later years and was honored by the Arab Women Journalists Center for her trail-blazing role in media.

Budeiri passed away in June 2009 at the age of 86, three years after the passing of her husband in Jordan. Her dream had been to be buried in Jerusalem. In an interview with Sami Kleib of Al Jazeera one year before her death, she expressed her grief and longing for Jerusalem:

I was born in Jerusalem, and my family is in Jerusalem. But if I am to ask them [the Israeli authorities] for a permit, they won’t allow me to go there. They are afraid that I will go and die there, or that I will get ill and stay there. It’s really painful . . . Life is painful.8

“Jerusalem for me,” she added, “is the most beautiful city in the world.” When asked if she would go back and live in Jerusalem should she be given the chance, her answer was: “I would go running.”9

She was buried in Jordan.

Sources

“Early Palestinian Press (1900–1948) & Huna Al Quds Radio Station (1937–1948).” Darat al-Funun. June 25, 2017.

“Jerusalem Calling.” Palestine Filmer C’est Exister.

Kanaaneh, Moslih, Stig-Magnus Thorsén, Heather Bursheh, and David A. McDonald. Palestinian Music and Song: Expression and Resistance since 1900. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Kleib, Sami. “Fatima al-Budeiri: Memories of Displacement and Radio Work.” [In Arabic.] Al Jazeera. Special Visit Program. March 3, 2008.

“Palestinian Women: Women and Feminist Personalities from Palestine.” [In Arabic.] Qalqilya Times. Accessed April 12, 2022.

Saadeh, Ali. “Fatima Budeiri: The First Arab Woman to Broadcast through the Microphone of ‘Huna al-Quds.’” [In Arabic.] Arabi 21. June 14, 2021.

Sahhab, Elias. “‘This Is Radio Jerusalem . . . 1936.’” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 20 (2004): 52–55.

Stanton, Andrea. This Is Jerusalem Calling: State Radio in Mandate Palestine. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Fatima Budeiri.” Accessed April 12, 2022.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Fatima Budeiri.” [In Arabic.] Last modified June 25, 2021, 14:34.

Ya‘qub, Aws Dawud. “Fatima Musa Budeiri.” [In Arabic.] Jana. Accessed July 13, 2022.

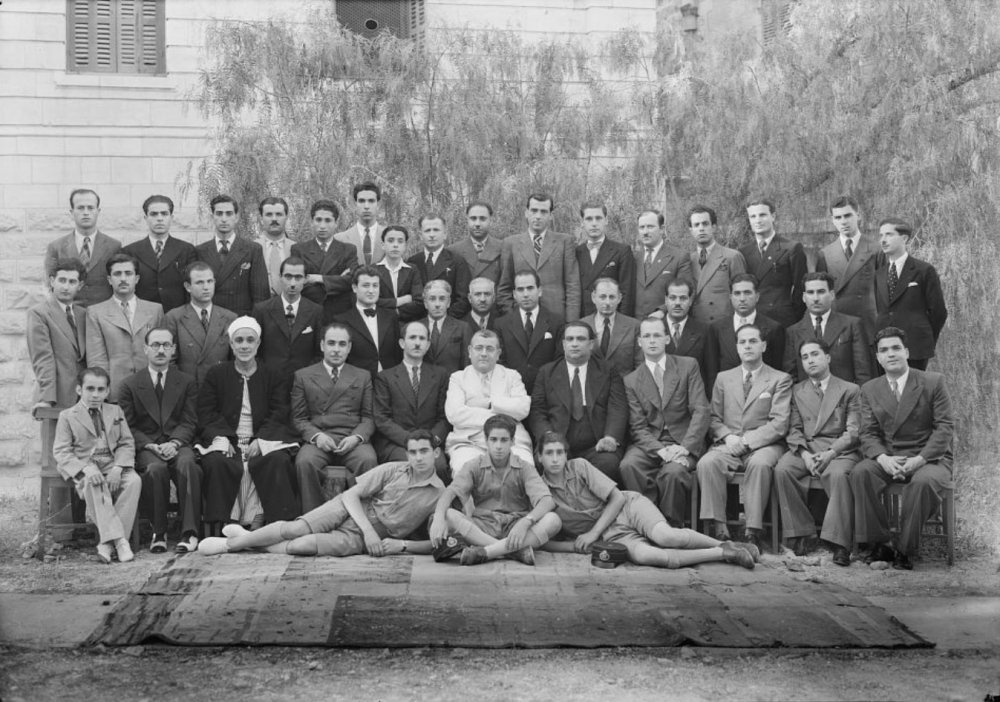

[Profile photo: arabi21]

Notes

Elias Sahhab, “‘This Is Radio Jerusalem . . . 1936,’” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 20 (2004): 52–55.

“Jerusalem Calling,” Palestine Filmer C’est Exister. The page provides a link to the documentary trailer.

Sahhab, “‘This Is Radio Jerusalem . . . 1936.’”

Sami Kleib, “Fatima al-Budeiri: Memories of Displacement and Radio Work” [in Arabic], Al Jazeera, Special Visit Program, March 3, 2008.

Kleib, “Fatima al-Budeiri.”

Kleib, “Fatima al-Budeiri.”

Andrea Stanton, This Is Jerusalem Calling: State Radio in Mandate Palestine (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013).

Kleib, “Fatima al-Budeiri.”

Kleib, “Fatima al-Budeiri.”