Background

Credit:

Oren Ziv

Challenged, the Police Back Down and Remove 10 Internal Checkpoints from Sheikh Jarrah

Snapshot

A conversation with attorney Suhad Bishara of Adalah, who filed, on behalf of residents and community organizations, the petition that compelled the city of Jerusalem to remove 10 internal checkpoints from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of Jerusalem just three weeks after they installed them.

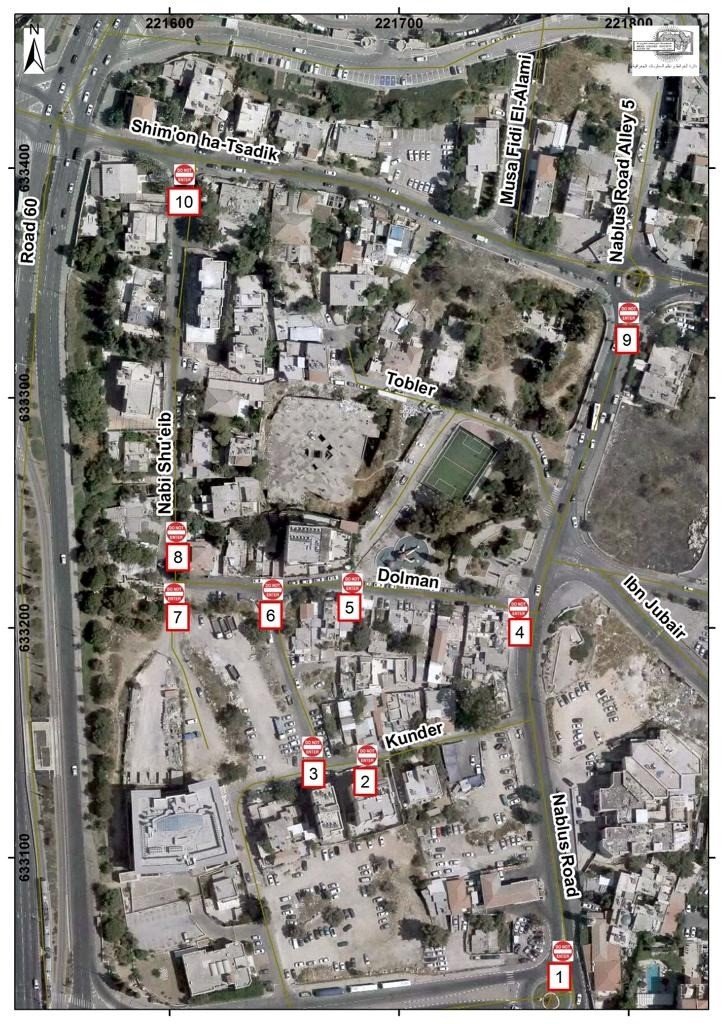

On February 13, 2022, Israeli MK Itamar Ben Gvir (Jewish Power Party) provocatively established a parliamentary “office” in the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem. This neighborhood has been a major flash point in recent months because of intense efforts by Jewish settler groups to take over Palestinian homes by forcing expulsions of Palestinian families. Shortly thereafter, the police erected 10 internal checkpoints in one small part of the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, the western part. This renewed fears that the police aim to “Hebronize” the Palestinian neighborhood.

On March 6, 2022, Adalah—The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, in coordination with the Civic Coalition for Defending Palestinians’ Rights in Jerusalem, filed a petition to the Israeli Supreme Court on behalf of seven residents of the neighborhood and the Welfare Association of Sheikh Jarrah, demanding the immediate removal of these 10 checkpoints. Attorney Suhad Bishara, who filed the petition on behalf of Adalah, said at the time,

Placing the checkpoints in Sheikh Jarrah is racist, illegal, and fundamentally unacceptable. The checkpoints serve as collective punishment and as an attempt to prevent legitimate protests and support for Palestinian families threatened with forced eviction. The police have no authority to set up these checkpoints, and the Supreme Court must order their immediate removal.1

The very next day, March 7, the police removed the checkpoints in a rare legal victory for the Palestinian community.

We spoke with attorney Bishara by Zoom on April 4, 2022, to learn more about this important case and its larger implications.

Jerusalem Story: Thank you so much for speaking with us today. Can you start by telling us a little bit about yourself?

SB: I’m Suhad Bishara. I’m the legal director of Adalah—The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel. I am also the Land and Planning Unit Director. So I pretty much touch upon all human rights-related cases of Palestinians in the Green Line and also in the occupied territories.

JS: Today we want to talk about a recent case that your office successfully litigated, and that’s the case of the 10 checkpoints that were placed inside the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in East Jerusalem. What does it mean when we say that these were internal checkpoints inside a neighborhood? And why were they placed there?

SB: The checkpoints were placed in part of Sheikh Jarrah. It’s a very small area of Sheikh Jarrah. They were placed for two reasons: One, because of the demonstrations protesting the attempts to evict one of the Palestinian families in that area; and the second, the decision of MK Itamar Ben Gvir [leader of the far-right Israeli party Jewish Power] to set up a makeshift parliamentary office in the area. So they installed the checkpoints before and after [that]. They’re trying to forbid anyone except those who are related to him to enter the area where he put this parliamentary office, affecting predominantly the Palestinians and the activists who come to support their cause.

JS: What if you live in the neighborhood, would you have to go through a checkpoint? Could you be stopped and not be able to access your house?

SB: Yes. There were 10 checkpoints. Three of them were permanent, surrounding the MK’s construction, not allowing anyone in. And seven other [checkpoints] in the surrounding area that were on and off [sporadically] during the day, which basically meant that all Palestinian residents in that area who wanted to enter had to prove their residency in the area. They had to pass through a checkpoint and present an ID with an address. Some were questioned. Their children who wanted to come back alone from school or any other activity could not enter freely unless they were accompanied by an adult who has identification proof that they are his children; they live in the area. This affected ordinary people, because you can send your children to school, but they cannot come home alone. Someone needs to be available in the area to allow them to pass the checkpoints. So children became less independent. Of course time management looks completely different. You’re not free to go around the neighborhood. Children are afraid to go out and play in the neighborhood. No one outside [the neighborhood] who came either for social purposes or to support the Palestinian families could enter; no one outside the neighborhood could be allowed in.

JS: And would that include Jews who are coming to protest in support of the residents? That would include citizens?

SB: Any supporters, regardless of their identity, were not allowed to enter.

JS: But the Jewish settlers who live in the neighborhood, were they affected by the checkpoints?

SB: Well, yes, according to witnesses and testimonies that we have from the residents, they were not questioned or were questioned less as far as people could tell. I mean, you have to be there at that moment [to know], but generally the [impression] we got from residents of the neighborhood is that they [Jewish residents] were not questioned. They entered and left more freely. And so I would assume that they were affected, but less than the Palestinians, who were the target of the checkpoints, basically.

JS: To clarify one point you made before about the children: The reason they have to be with a parent is that they don’t have their own ID cards until they’re 16. So they’re only registered on the parents’ IDs, right? So they can’t show a document to get through the checkpoint.

SB: Yeah, children below age 16 don’t hold IDs or aren’t required to. So you have to be accompanied by a parent who has you registered on their ID card with the address in that neighborhood.

JS: So it was to show the ID with the address that you live there, that’s what gets you through the checkpoint.

SB: Definitely.

JS: How long were these checkpoints in place this time?

SB: Around three weeks—until we petitioned and then one or two days after they just dismantled everything. By the time we filed the petition, it was over three weeks.

JS: Was this the first time that internal checkpoints had been placed in Sheikh Jarrah, or is it a common or not a new situation?

SB: It’s not a new situation. Every time there is a protest or demonstration, people come to support threatened Palestinian families—threatened in terms of evictions—there are checkpoints. We have seen that in the past, although 10 checkpoints in one small area—we haven’t seen that before. There was one checkpoint in another part of Sheikh Jarrah last year that was placed to basically try to control who enters and who leaves—basically who enters—as one checkpoint at the main entrance of the area. The map of the checkpoints this time looked completely different. It basically cut a small area into even smaller areas. Even people in the same neighborhood, it was really hard to visit each other and socialize. This is why it was also harder for children to go out and play outside, because you had checkpoints on and off, all around you, so it’s not only in the entrance to the neighborhood, but also cuts the neighborhood itself to smaller parts.

JS: And what did that signify to you or to the residents? What did they see might come from that fracturing of the neighborhood—What was the intent behind that for the future, if the checkpoints had stayed?

SB: Well, imagine that you leave your house and you face a checkpoint. Imagine you come to your neighborhood with your children and you want to enter your house, your neighborhood, and you have to pass through a checkpoint to prove you live there, maybe to answer a few questions that have no justification, just to simply to leave your house, go to do groceries, take the kids for school, go to work, and come back to the comfort of your home. So it becomes an obstacle to leave and to come back to your home, in a very simple manner. I mean, your home—it’s not safe anymore. You have all of these checkpoints, a security official standing there all the time, checking everything, checking you, coming in and out. So it doesn’t feel home anymore; it’s like you’re trapped in there. You’re afraid to look out of the window; you’re afraid to send your children out. Yeah? It’s like you’re in a spacey prison; you’re confined; you’re restricted, you’re not free to move as you wish anymore. People who you love, people who you care for, are not free to come and visit you anymore. So it affects interactions on all levels—economic, social, political, of course, affecting those who want to support and people needed that support—it was very important. It’s a political issue.

So your days look different. Your agenda looks different. Your time looks totally different. Your surroundings look different. You look out of the window, you see different scenes. So nothing stays the same.

JS: What is the legal authority by which Israel can do this in Jerusalem? This is not the West Bank, right? It is not military occupation. So what is the legal authority that they use to put these checkpoints up in Jerusalem?

SB: It’s illegally annexed. It’s occupied territory. But Israel applies, forces its laws in the area, and according to these laws, Israeli police authorities—this is what we argued in the petition that we filed—has no authority whatsoever under the circumstances to put checkpoints in such a manner. It’s not an issue of public order. They’re restricting the movement of people. These restrictions are affecting their social life, their economy, their freedom of movement, obviously. Under no authority.

JS: So they actually don’t have a legal basis on which to do it.

SB: This is what we argued in the petition, yes, that under the circumstances, they have no authority, even under Israeli law, to put such checkpoints in that small area.

JS: Have they ever done that in a Jewish neighborhood in Jerusalem, to your knowledge?

SB: Well, I haven’t researched that; I don’t know. The only example that I could think of is during the demonstrations in the Jewish religious neighborhoods. Not that I know of—but I cannot be certain honestly. But usually there, when they had the big demonstrations, it’s usually trying to control the crowd rather than putting checkpoints and not allowing people in and out. And I haven’t heard of that in Jewish neighborhoods. I don’t know for certain.

Of course, you cannot ignore the fact that one of the goals and aims of these checkpoints is control. One of the aims is to try to control the protest, to prevent people from coming and protesting, and so it’s an oppressive tool in itself—beside the daily effect on the people living in the neighborhood. One of its major goals in my view is to suppress the protest and to prevent people coming in and supporting the Palestinian families. This is one direct effect of these checkpoints.

JS: Let’s turn now to the case that you filed. On whose behalf was this case filed? Was it a specific family or a person? And how did Adalah come to take the case? Then we can talk about what the arguments you made.

SB: The case was coordinated with the Civic Coalition for Palestinian Human Rights in East Jerusalem. It’s a coalition of Palestinian human rights organizations active in East Jerusalem, and it was filed on behalf of the residents of Sheikh Jarrah as well as the NGO Sheikh Jarrah Welfare that’s active in the community in Sheikh Jarrah.

JS: How many families were involved?

SB: I believe it was seven individuals representing different families, and the Sheikh Jarrah Welfare NGO represents of course the larger community. It was a test case, so it was enough to have several affected families or individuals even in order to have a standing before the Supreme Court under these specific circumstances.

JS: So the case was argued before the Supreme Court?

SB: Well, we didn’t get to a hearing, luckily. We filed the petition and then a day or two later, I received information that they’re dismantling all of the checkpoints. They took everything away, and people became free to move without any checkpoints.

JS: Tell us a little bit more about the arguments that were in this filing, and why they were legally convincing to the court—why you think that they had no choice but to backtrack on this situation.

SB: We had two types of arguments. One is administrative, basically arguing that the police have no authority and they function against the rule of law. And again, under the circumstances, there was no justification to put such checkpoints in. The second was constitutional, meaning that the checkpoints affected the constitutional rights and human rights of the residents, as well as any other supporters who wanted to come in and protest and to express their support for the affected families in their eviction attempts. And that was for a nonlegitimate purpose.

And of course it was extreme, because you had quite a lot of checkpoints that we haven't witnessed before, in such a manner. But when they dismantled it—once we filed the petition—the court asked for the attorney general, which represents the police. They respond within 10 days and [on] the 10th day, they responded that they took everything out based on reassessment of their considerations. And so basically the court said, we, the petitioners, needed to decide whether to withdraw under the circumstances, which only made sense.

JS: You then withdrew the petition because the situation was no longer—

SB: Because we got what we wanted. No more checkpoints.

JS: Most of the Palestinians living in Sheikh Jarrah—they have permanent resident status, right? They’re not citizens. Are they entitled to the same rights as citizens would be, or is there some difference because they’re residents?

SB: It depends on which package of rights you are talking about. In terms of the effect of the checkpoints and affecting their right to movement as well as the other affected rights surrounding movement, such as going freely to your workplace, children coming back from schools or any afternoon activities, economy, and so on—yes, it was based on both human rights law and Israeli constitutional law that was applied on the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem, which by itself should be granted to every human being, resident or citizen, theoretically speaking, with no difference with your status.

JS: That’s important.

SB: Yeah. But when you speak about other sets of constitutional rights, that might differ, of course. That isn’t necessarily equal in other situations of constitutional rights.

JS: How do you see the significance of this ruling in a broader sense for Palestinians of Jerusalem? How important is it as far as precedents being set or established? Will this obligate the government or the police in the future—prevent them from ever doing this again? Or is this just a one-off case and they could come back and do it and you’d have to fight it again?

SB: I wish I could say that they won’t do that again. Unfortunately, I expect that they might either in Sheikh Jarrah or any other place in East Jerusalem.

First of all, it’s not a precedent, because there is no ruling. Because the dispute, you know, was resolved before we even reached a hearing in the Supreme Court. So the Supreme Court did not need to issue a ruling that is precedent-setting, let’s say. If the Supreme Court had to issue a ruling saying that the police has no authority, then the police cannot do that anywhere else under the same circumstances. But since we’re not there, so there is no ruling, and there’s no precedent.

My assumption, as always happens—this might happen again. And, of course, the police can—as they always argue—that there are, you know, public order and public security considerations, and so on.

Now the legal question, of course, is under dispute. The police might argue that they have an authority, and we obviously argued that they don’t, under the circumstances. They cannot just say walla, there are demonstrations here. There is a potential, whatever— tension in the air—so let’s put checkpoints and restrict the movement of people. We argue that you cannot do that; it’s not as simple as that. And the considerations that allow them to put checkpoints are very, very, very narrow and very extreme circumstances. Which did not exist in the case of Sheikh Jarrah. So unfortunately, they might do that, since there is no ruling saying that they don’t have authority. But again, then the people and human rights organizations would have to challenge that on a case-by-case basis. Unless in one of the cases a ruling is delivered by the Supreme Court saying there is no authority.

JS: Do you think they resolved it before it could get a hearing for that reason, so as to avoid setting a precedent? Or were they just backing down quickly because they knew they were in hot water?

SB: It’s really hard to know, because the way they drafted their response, they try to avoid. Of course, they tried to defend their position and their authority as they perceive it, to put checkpoints. So it remains a question in legal dispute between human rights organization—Adalah, definitely—and the police and attorney general in this case. Sometimes it takes several cases to build up to get a ruling. And it seems this is one of them. Hopefully they won’t do that again, because they know people are aware and they know people would approach the Supreme Court again, and again if needed. So we’ll see.

JS: Can you elaborate on what their response was? You said “they tried to avoid.” “Tried to avoid what?” going to a hearing? And legally, how was that like?

SB: Basically, according to the Supreme Court decision, they had to submit their written position in regards to our argument’s petition. And of course they tried to defend that they have the authority under Israeli law, the way they interpret the law, and usually they do that in a very broad way. They try to give the police very broad authority to do whatever they perceive [is] needed for public order and defend the security of the public.

So this is their legal position. And this would be their position I assume also in future cases. This is why at some point the Supreme Court would have to decide.

Now the other option in this regard is whether through time—but it needs a lot of examples where you can prove to the Supreme Court that there is a policy here—then you can challenge principly [the principle of], the policy as such, and the decision of the police to put checkpoints once again under circumstances, which is a harder case to bring to the Supreme Court, because the police will usually argue that each case has different circumstances; you cannot see this as a policy; and so on—we have discretion in each case. We thoroughly think about it, we thoroughly think about the consequences. So it’s a harder legal case to make; it’s a harder case to prove; and it takes a lot of time because you need to prove a policy, so it takes a lot of cases. I hope we won’t get there, because we don’t want a lot of cases. It affects a lot of people. But this is another option to challenge.

JS: You said that the circumstances under which they could legally put up checkpoints were very narrow. Can you tell us what those circumstances might be? In what situations would it be legally allowed for them to do what they did?

SB: There is nothing very explicit, but trying to read the law in context. This is what they commonly do when you have intelligence information that you have a drug dealer trying to move drugs from place x to place y, and you want to erect a checkpoint to catch him. This is one example. As long as you do this in a proportionate way—meaning that you cannot, let’s say, decide to put a checkpoint and close the entrance of a city, or the only entrance of a city that holds 200,000 residents.

JS: Like what’s done in the West Bank?

SB: Yeah, something like that. So it’s not only that you have to have the authority to do it; you have to do it in a proportionate way. You have to check other methods that are less harmful and affect less the rights of other people. So there’s no black and white. Even if you have authority, that doesn’t mean that under all circumstances you can. There are still other considerations, and other people’s rights to consider.

JS: Thanks so much for speaking with us today to shed light on this important legal milestone.

SB: Thanks for having me.

Notes

“Adalah Petitions Israeli Supreme Court to Remove Checkpoints in Sheikh Jarrah,” Adalah, March 6, 2022.