Jerusalem Interrupted: Modernity and Colonial Transformation, 1917–Present, edited and introduction by Lena Jayyusi (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2015).

***

Jerusalem today is closed off not only to the entire Arab world but also to Palestinians in neighboring towns and cities, its residents hounded, and al-Aqsa Mosque the site of confrontations between worshippers and armed Israeli soldiers and settlers.

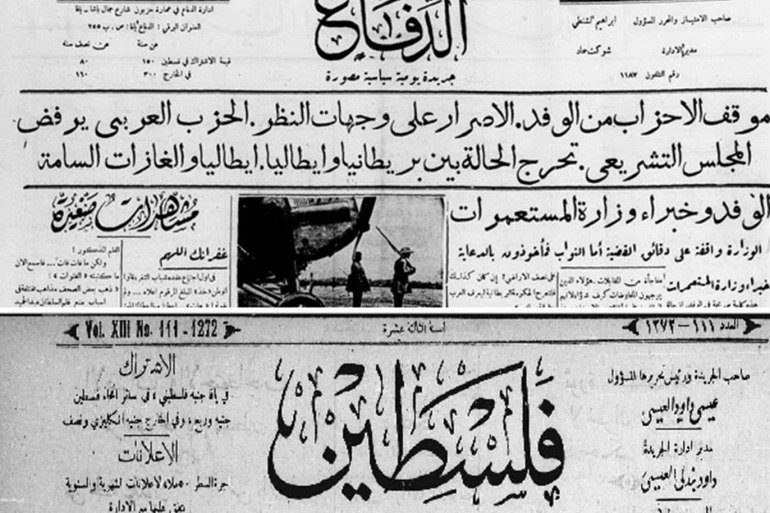

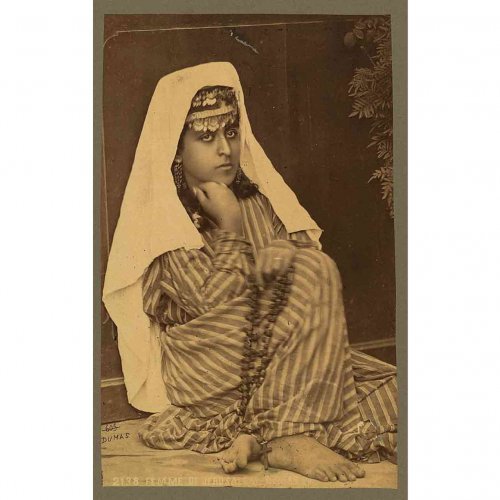

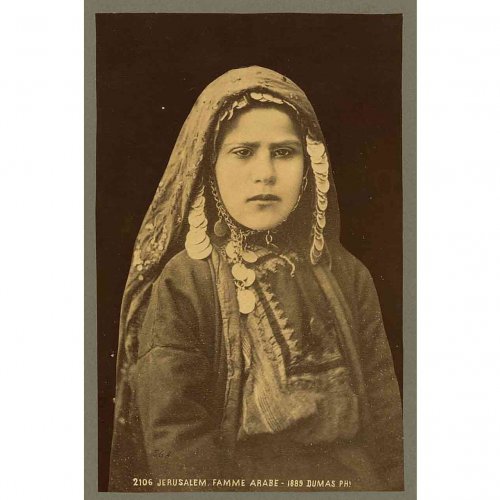

It is soothing, then, to imagine the Jerusalem of the early 20th century that the editor describes in the “Introduction” of Jerusalem Interrupted, winner of the Palestine Book Award in 2015. Here we meet Jerusalem the urban, cosmopolitan center connected to other regional capital cities—Cairo, Damascus, Beirut, Istanbul—through kinship, commerce, cultural practices, and other activities. It is a dynamic city of the arts, hometown to a host of cultures and ethnicities who lived together as harmoniously as can be expected in any city undergoing rapid change. As editor Lena Jayyusi (also a communications and media expert) explains in the “Introduction,” the natural transformations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries came to an end in 1948. After that year’s war and Palestinian exile, changes that suited foreign political interests would be grafted onto the city.

Not surprisingly, then, this cataclysmic event defines the two parts of the book; there is a before 1948 (part I) and after 1948 (part II). Before 1948, Jerusalemites were involved in creating and responding to changes in the region. After 1948, the city was controlled by nonindigenous forces that single-mindedly focused on redefining the space to make it exclusively and unalterably Jewish. This is a narrow, shabby plan for a city that in the early 20th century was poised for so much more. The final chapter of the book provides a vision of the future with possibilities and alternatives to the current dead end.