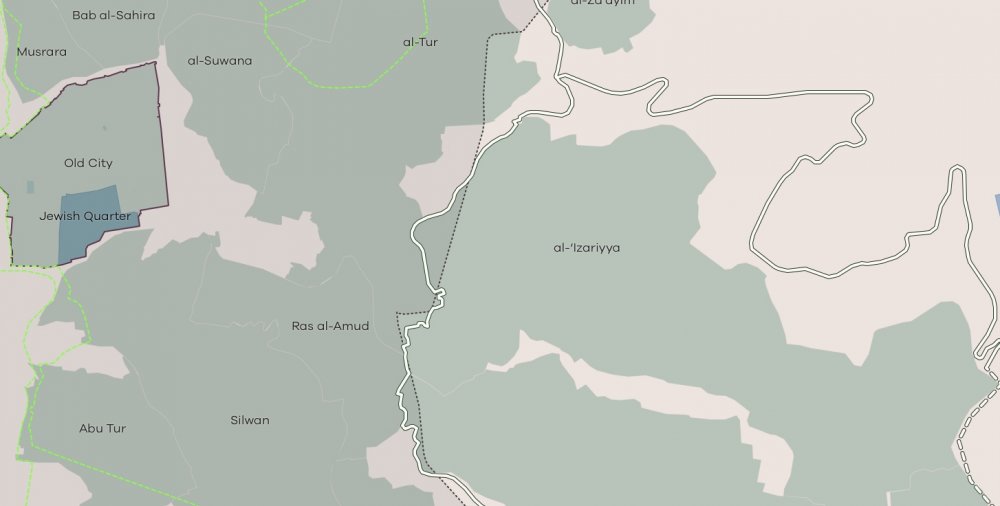

Ahmad,1 25, from al-‘Izariyya, expressed how narrow the scope of his life felt in the village after its full besiegement by the wall and surrounding settlements—“min el-duwwar lal-jidar” (“from the roundabout to the wall”).

He also described how local residents find it difficult imagining any future, when life is restricted to a zone alongside a wall, on the one end, and an ever-expanding settlement bloc, on the other. Locals would jokingly say, “biqdaru yea’eqdu wa-ysawu tabiq tani fuqna” (“they could just say the hell with it and build a second floor on top of us”).

The wall disrupts the social well-being of the communities it dissects, as it separates them from educational and health infrastructure. Ahmad described how, before construction on the wall began in 2004, he used to attend a good school in al-Tur, where he studied alongside classmates from diverse backgrounds from all around East Jerusalem. This, he said, made him feel part of a bigger society.

The wall forced families to move their children to schools within their own neighborhoods. For Ahmad, this meant attending subpar schools in al-‘Izariyya with limited resources and unqualified teachers. It also put an end to the diverse life he knew in al-Tur, and to socialization beyond the bounds of al-‘Izariyya more broadly.

Ahmad’s father, an air conditioning technician, also suffered as a result of the wall. He lost many customers, both Arab and Jewish, on the other side of the wall, and he had to work with the limited local clientele, dramatically reducing his income.