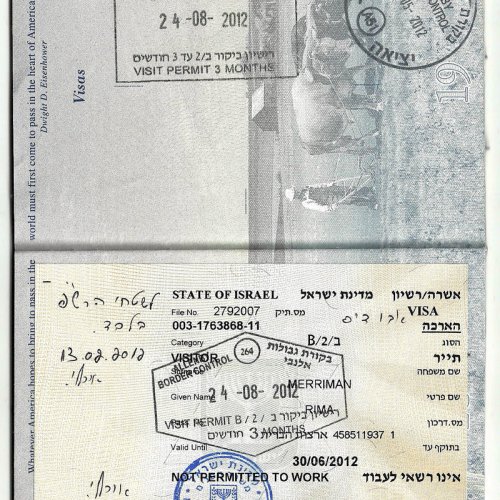

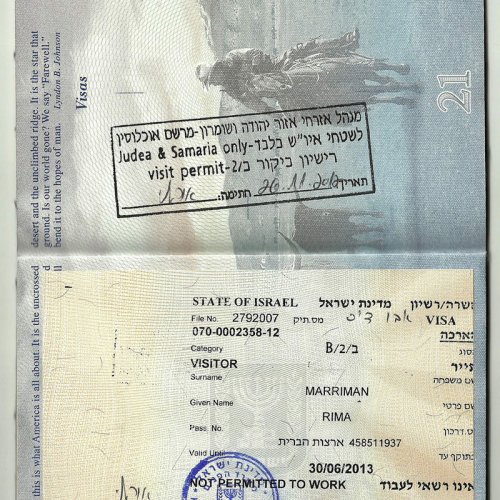

Travelers to the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt) are accustomed to various forms of harassment, invasive security checks, and even being denied entry at the border, which is wholly controlled by Israel.

But on October 20, 2022, new “procedures for entry and residence of foreigners living in the Judea and Samaria Area”1 went into effect that dramatically stifle foreign passport holders’ ability to travel to the occupied West Bank—even if they have family or business there—if they are associating with Palestinians.

These regulations isolate Palestinians holding Palestinian Authority (PA) IDs living outside the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem in the West Bank and prevent them from enjoying the right to family, education, healthcare, a normal economy, access to expertise from the outside world, and more. They also sharply limit the ability of Palestinian organizations in the West Bank to benefit from international engagement, including from Palestinians holding foreign passports.

The end result will be the isolation of Palestinian society in the West Bank and intense pressure to emigrate on families that include foreign passport holders.

These procedures, Israel says, are an answer to calls that it formalize the process for visiting and residing in (i.e., entering) the West Bank.

In reality, the new procedures—a revision to an earlier version that was widely criticized—are part of policies designed to push Palestinians out, limiting Palestinian demographic growth and achieving Israel’s aim of controlling the West Bank permanently through demographic hegemony. In the words of Human Rights Watch: