The Aftermath of the 1948 War

The West Side Story, Part 4: The Erasure of the New City and Its Transformation into Jewish West Jerusalem

Snapshot

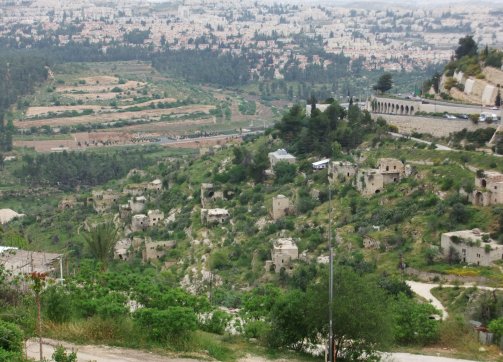

In the aftermath of the 1948 War, Jerusalem was divided into a Jewish west side and an Arab east side. What was once the New City became West Jerusalem, an exclusively Jewish area that came under Israeli sovereignty. East Jerusalem, including the Old City, came under Jordanian control and remained largely Arab until it was occupied by Israel in 1967.

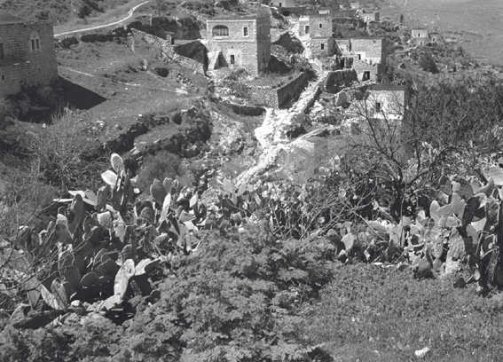

As a result of the 1948 War, tens of thousands of Palestinians from the New City and its surrounding villages were dispossessed and forced into exile, to this day. While some were able to take refuge and subsequently settle in East Jerusalem, a short distance from their original homes in what became West Jerusalem, thousands were rendered stateless refugees, and many remain in refugee camps in neighboring countries.

None of these Palestinians have been allowed to return, and none have been compensated for all that was taken from them.

Part 4 of a four-part series. View Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

Erasing Palestinians and seizing their properties

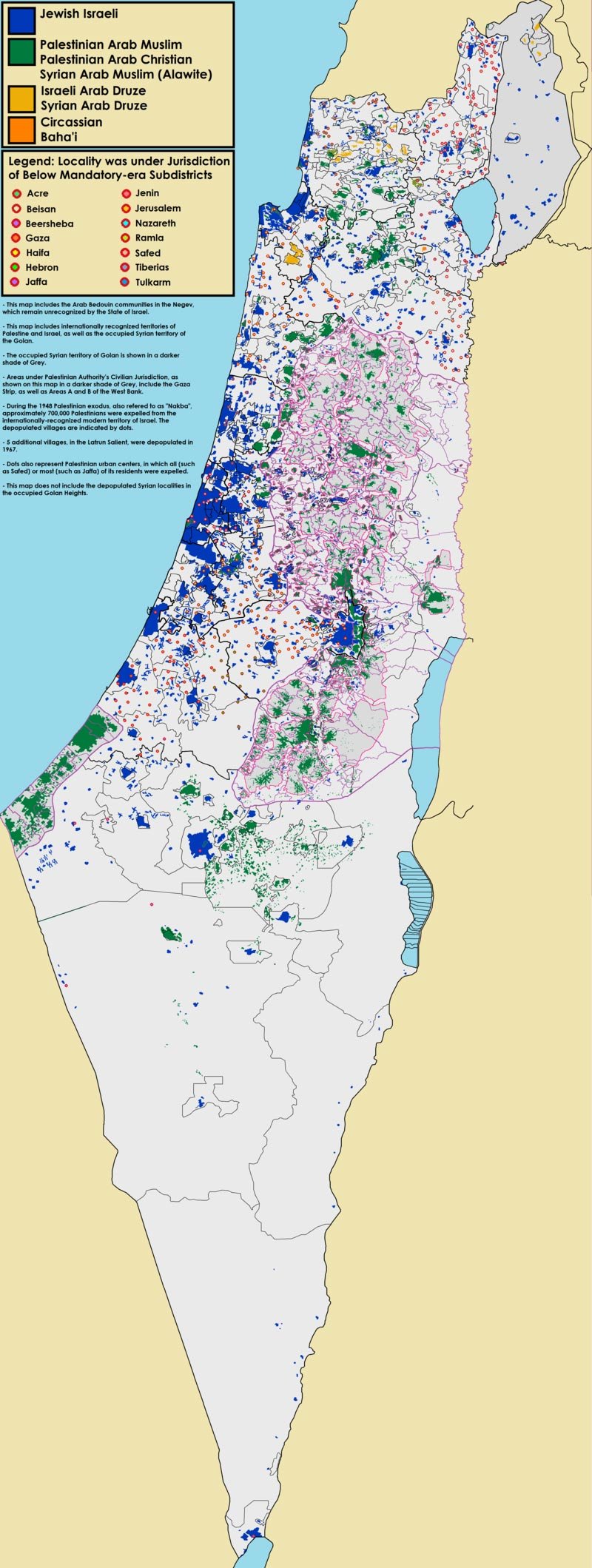

Ultimately, it is estimated that 73,256 Palestinians were erased from Jerusalem and its surrounding villages by the end of 1948, a process of depopulation that spanned nearly 300,000 dunums of land, or approximately 3,000 square kilometers.1 This, to be sure, was only a part of the depopulation that occurred across Palestine, a process that resulted in the exodus of an estimated 750,000 Palestinians.2

Although most thought they were leaving an area slated to become an international zone for only a short respite from the violence, Israel subsequently seized the western side of the city and its surrounding villages, declared sovereignty over them, and banned the Palestinians from ever returning.

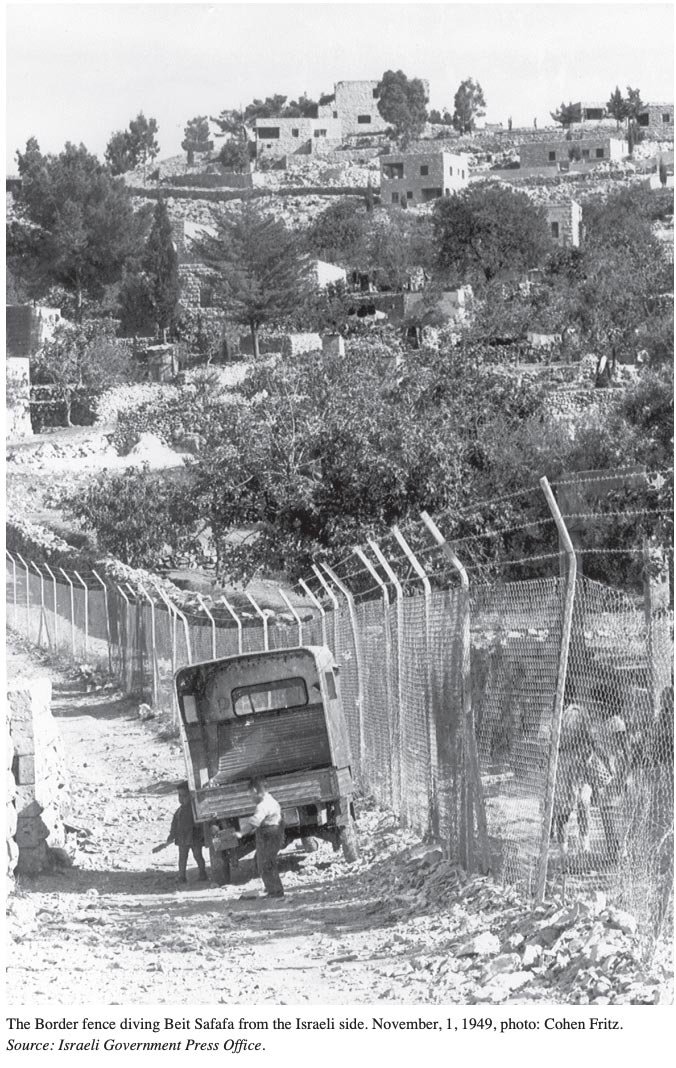

Only about 750 non-Jewish individuals remained in West Jerusalem after the war, “and of those 550 were Greeks who continued to live in their houses in the German and Greek colonies.” It is therefore estimated that the remaining 200 were Palestinians, a number which amounts to “less than half a percent.”3 The number of non-Jews left in West Jerusalem was negligible and remains so to this day. According to Romann and Weingrod, “All of West Jerusalem—that is, the section of the city that was Israeli since 1948—remains an almost exclusively Jewish zone.”4 Indeed, the most updated demographic data reflect that in 2019, West Jerusalem was only 1 percent Arab.5

Thus, in the area that subsequently came to be known as West Jerusalem, the process of de-Arabization was complete. David Ben-Gurion, leader of the Jewish community in Mandate Palestine (known as the Yishuv) and later Israel’s first prime minister, took great satisfaction in this outcome, as he expressed even as early as February 1948:

. . . from your entry into Jerusalem, through Lifta, Romeima . . . there are no Arabs. One hundred percent Jews. Since Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans, the city has not been so Jewish as it is now. In many Arab neighborhoods in the west [of Jerusalem] one sees not a single Arab. I do not assume that this will change.6

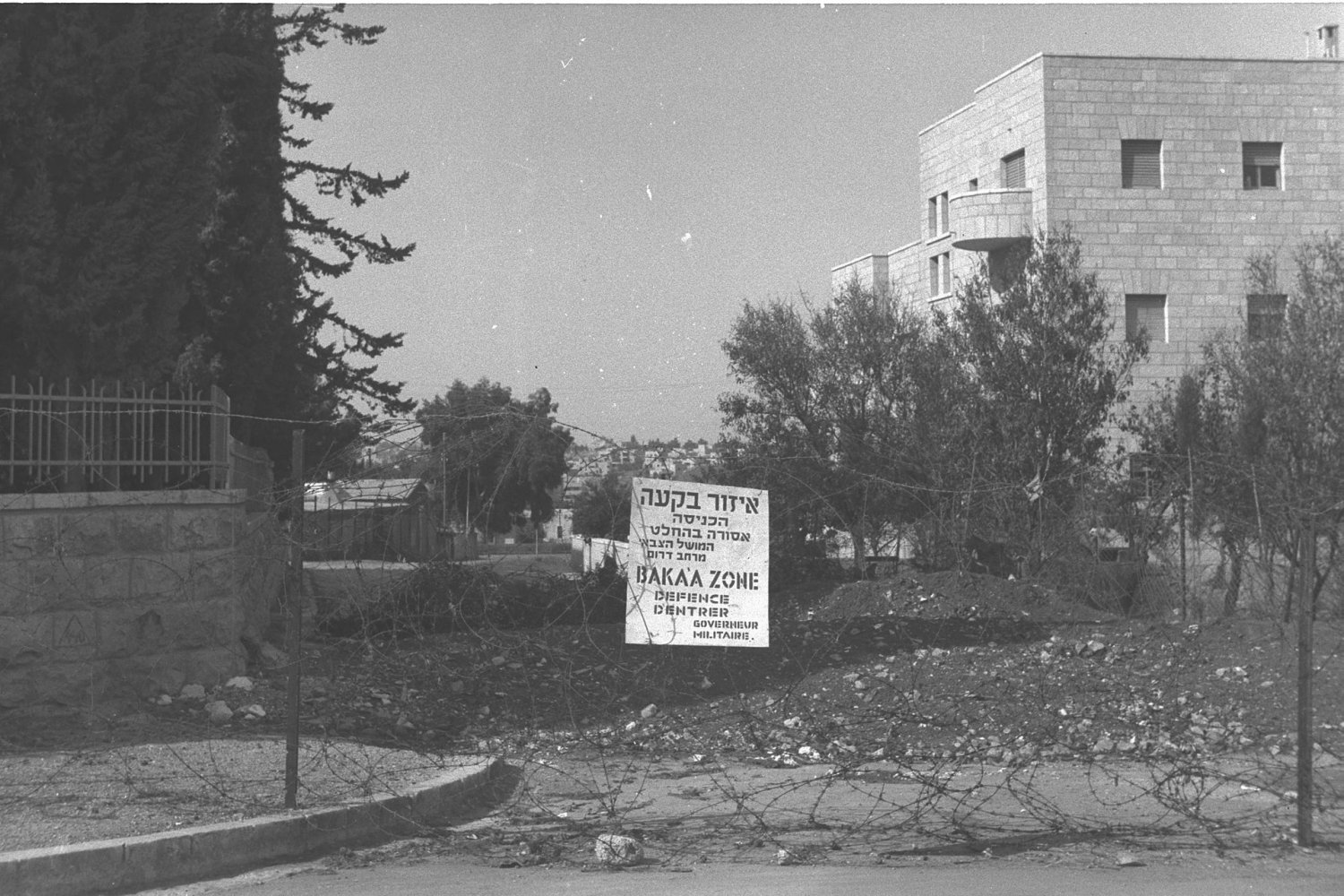

The remaining 200 Palestinians were forcibly confined to a “security zone” in al-Baq‘a neighborhood, known as the Baq‘a Zone or Zone A, for two and a half years. Jacob Nammar, whose family had owned property in the Nammara neighborhood of al-Baq‘a, wrote about his family’s experience in his memoir. They were forced at gunpoint to move to a partially finished apartment near the railroad tracks.7 Nammar relates:

One day several Jewish soldiers came with a bunch of armed men to our home [in West Jerusalem]. They showed up under the pretense that they wanted to help us. They insisted that it was no longer safe for us to stay in Haret al-Nammamreh and demanded that we relocate to another neighborhood. They said it was for our own protection, that it would be “only for a few days” and that we would be back “soon.” My spirit sank. After futile argument, my mother and all of us seven young children locked our home, secured the key, and against our wises left our home. All we took were the clothes on our backs and a few personal belongings; everything else we left behind.

At that moment we realized that we were the last of the Nammamreh family to leave our neighborhood . . . .

We quickly discovered that we had been forced under military administration law into a fenced security zone (Zone A), confined with Palestinian families from other neighborhoods who had also stayed in their homes . . . The military zone was a ghetto and a large open prison camp, surrounded by eight feet of barbed wire, with armed guards preventing anyone from leaving or entering.8

They were forced to live there for two and a half years without schooling, work, or assistance of any kind.

When they were finally allowed to leave the zone, they found their homes had been confiscated and given to Jews, either new immigrants or former residents of the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. The Nammars were suddenly homeless. For legal status, they were granted only differentiated blue identification cards, even before Israel had decided that Palestinians from Jerusalem should be made permanent residents, not citizens, which happened much later in 1967. Stranded and helpless, with a father and brother imprisoned, they had no choice but to return to the same apartment in the zone where they had been confined.

As for East Jerusalem and the remainder of the West Bank, Jordanian forces took control. On April 3, 1949, Jordan and Israel signed an armistice agreement which confirmed Jordan’s annexation of these Palestinian territories, including the Old City. Both Israel and Jordan preferred a partition of Jerusalem to its internalization, as the latter would mean loss of power for each. Fearing a new step towards the internationalization of Jerusalem due to an upcoming UN vote on Resolution 303, Israel declared West Jerusalem as its capital in December 1949.

By the start of 1950, therefore, “West” Jerusalem’s original Palestinian inhabitants had become landless refugees with no claims to their properties and bank accounts; they were subsequently never allowed to return, and have never been compensated.9 As the Nammar family story indicates, with the end of the mandate and the declaration of the new State of Israel in May 1948, Palestinians who had the previous day been citizens of Palestine were “rendered stateless overnight; many of them were homeless, and the vast majority of them were by then also refugees.”10 This left them utterly defenseless.

The UNRWA registry holds records of all Palestinian refugees who sought relief services and shelters in one of the five UNRWA field areas stationed in the West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Since a significant number of Palestinian refugees from the New City were of middle and upper classes, many of them do not appear in the UNRWA records. That is, “approximately 30 percent of Palestinian refugees from Jerusalem and the four villages incorporated into the western part of the city [i.e., ‘Ayn Karim, Deir Yasin, Lifta, and al-Maliha] . . . are registered with UNRWA.” The total number of registered refugees from these areas is 151,920, whereas the total for those who were not registered is 335,061.11 Most of the urban middle- and upper-class refugees who had substantial documentation for their property stayed in what became East Jerusalem, within eyesight of their homes in West Jerusalem. Many ended up in Shu‘fat and Qalandiya refugee camps on the outskirts of the occupied eastern side of the city. Poorer Jerusalemites and villagers of the western corridor of the city found refuge in UNRWA camps in Jordan before 1967. According to the Jordanian census of 1952, it is estimated that East Jerusalem, which came under Jordanian rule following the 1949 armistice, had a population of 46,700 Palestinians, thousands of whom were displaced from West Jerusalem.12

The Preconceived Plan to “Transfer” Palestinian Arabs

The plan to transfer Palestine’s Arabs upon the establishment of a Jewish state is as old as Zionism itself. As Nur Masalha argues, the idea of transfer “can be said to be the logical outgrowth of the ultimate goal of the Zionist movement,” which was the establishment of a majority Jewish state in Palestine.13 Indeed, Theodor Herzl dreamed that the Arabs would be “spirited across borders,” or that they would “fold their tents and slip away.”14 While earlier Zionist visions for depopulating Palestine were mostly that, ideas, they began taking shape into policies throughout the British Mandate, and specifically, in the 1930s and 1940s, by the Jewish Agency.

As early as the summer of 1930, Chaim Weizmann, president of the Zionist Organization from 1921 to 1931 and again from 1935 to 1946, and the first president of Israel, held secret talks with British Mandate officials regarding the transfer of Palestinian Arabs to nearby Arab countries, namely, Transjordan. While the British authorities refused this proposal and many others from Weizmann and other Zionist leaders throughout the 1930s, the Zionists persisted in defending their position that transfer was perfectly acceptable given similar population transfers, such as between Greece and Turkey.15

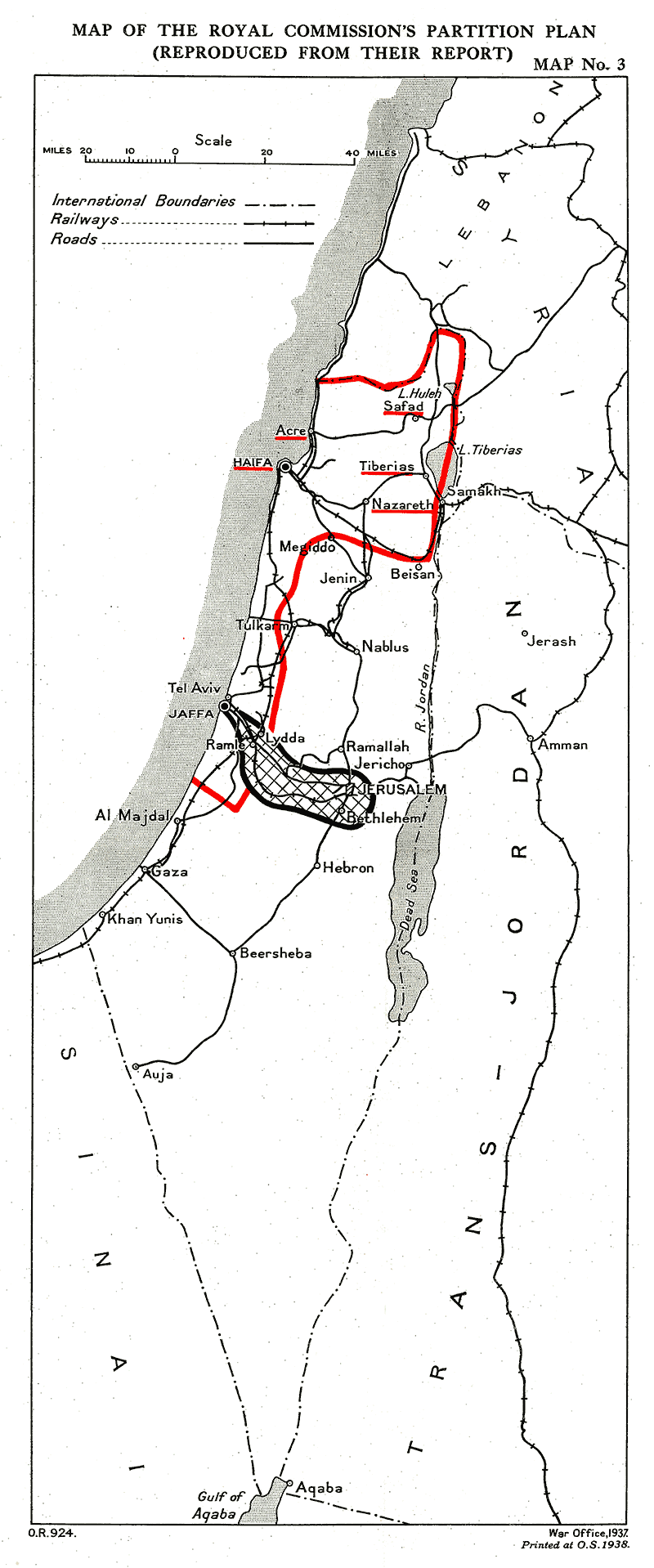

During the 1936–39 Great Palestinian Revolt, Zionist leaders pushed for legitimizing “forcible ‘mini-transfers’ of Arab tenant farmers” who worked on lands that were bought out by Zionists from absentee landlords.16 This coincided with the arrival of the British Royal Peel Commission in Palestine in November 1936 to investigate the months-long Arab strike that had caused significant unrest in Palestine. During the commission’s stay in Palestine, members of the Jewish Agency pressed for their transfer plan.

In May 1937, the Agency put forward a proposal for transferring Palestinian Arabs to Transjordan.17 And in July 1937, the commission issued its report which included recommendations for population transfers upon the creation of two separate states, one Jewish, the other Arab. This would entail the transfer of roughly 225,000 Arabs from lands that would become part of the Jewish state, and 1,250 Jews from what would become the Arab state.18 This report represented the first official British legitimization of the transfer of Arabs, no doubt due to intensive Zionist lobbying.

Following the commission, Zionist leaders debated the exact nature and parameters of these population transfers during the meetings of the Zionist Congress in 1937. As a result, a series of plans for transfer, whether compulsory or otherwise, were drafted by Zionists and presented to British authorities. This included the 1937 Soskin Plan of Compulsory Transfer, the December 1937 Weitz Transfer Plan, and the July 1938 Boneé Scheme, among others.

Zionist leaders also formed official and unofficial “transfer committees” that met throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, and even after the establishment of the Israeli state in May 1948, to further lay the groundwork for the policies that would ensure the permanent transfer of Palestinian Arabs following the 1948 War.

The first unofficial transfer committee meeting was held on November 15, 1937. In it, Yosef Weitz, director of the Land and Afforestation Department of the Jewish National Fund, presented a detailed transfer plan in which he laid out the steps for depopulating different areas of what would become the Jewish state. He listed three categories of Arabs: tenant farmers, landless villagers working as laborers, and farmers who owned less than three dunums per capita.19 He estimated that the total number of these Arabs was 87,300, and that 1,150,000 dunums would need to be purchased from Transjordan in order to transfer them. Weitz cautioned the committee that this would be costly and difficult, but that it would be feasible with careful strategy.20 Thereafter, committee members began strategizing, including by lobbying British authorities over the course of the late 1930s and 1940s. In early 1938, the “Population Transfer Committee” requested permission from the mandate government to access the land registry and tax offices in order to study the extent of Arab land ownership in Palestine, which the mandate government granted.21

Weitz was an ardent supporter of transfer. On December 31, 1947, during a meeting of Zionist leaders, he declared: “This is not enough . . . Is it not now the time to get rid of them? Why continue to keep in our midst those thorns at a time when they pose a danger to us?”22 And in a diary entry recorded in 1940, he intimated: “The only solution is to transfer the Arabs from here to neighboring countries. Not a single village or a single tribe must be let off.”23

While the details and outcomes of the series of “transfer committee” meetings and plans are beyond the scope of this Backgrounder, Weitz became a central figure in orchestrating what he termed the “retroactive transfer” of Palestinian Arabs following the 1948 War. That is, following the expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinian Arabs from Palestine at war’s end, most became refugees with the internationally recognized right of return. Yet Israel’s continual rejection of this right, Weitz said, amounted to “retroactive transfer” of the refugees to nearby countries.24

While the details and outcomes of the series of “transfer committee” meetings and plans are beyond the scope of this Backgrounder, Weitz became a central figure in orchestrating what he termed the “retroactive transfer” of Palestinian Arabs following the 1948 War. That is, following the expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinian Arabs from Palestine at war’s end, most became refugees with the internationally recognized right of return. Yet Israel’s continual rejection of this right, Weitz said, amounted to “retroactive transfer” of the refugees to nearby countries.25

Following the establishment of the Israeli state in May 1948, Weitz continued attending meetings of top Zionist leaders to present his plans for permanent retroactive transfers. On June 5, 1948, Weitz met with David Ben-Gurion and presented him with a three-page memorandum he had drafted with members of the transfer committee, and which he titled “Retroactive Transfer: A Scheme for the Solution of the Arab Question in the State of Israel.”26 Given the large number of displaced Arabs following the war, Weitz argued that the solution to the “Arab question” in the State of Israel “must from now on be directed according to a calculated plan geared towards the goal of ‘retroactive transfer.’”27

To actualize this vision of “retroactive transfer,” Weitz and the transfer committee called for preventing Arabs from returning to their homes, destroying remaining Arab villages, settling Jews in a number of depopulated villages and towns, promoting the resettlement of Arab refugees in other countries, and creating propaganda campaigns to counter return, among other stipulations.28 The memo was so convincing, Ilan Pappe argues, that even the most liberal of Zionists in attendance concurred that transfer was necessary for creating a Jewish state.29

Although Ben-Gurion and his main consultants did not officially grant Weitz permission to carry out his plan, Weitz and his cabal of zealous anti-Arab Zionists went on with the plan, and Ben-Gurion simply turned a blind eye to the atrocities they committed. What ensued was a campaign of destruction which leveled various Arab villages, a list of which Ben-Gurion kept in his diary with the help of Weitz.30 The list also included the size of the lands of each village and the number of people expelled from them. This campaign persisted throughout the remainder of 1948.

On August 18, Weitz’s plan was the topic of conversation between Ben-Gurion and senior Zionist leaders. The attendees unanimously supported the plan to block the return of any Palestinian Arab refugees,31 and even began speaking of creating a plan for resettling them regionally, especially in Transjordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. Ben-Gurion also appointed Weitz as leader of a new and official “transfer committee” to develop the transfer and resettlement plan further.32 As for the Arabs who remained throughout Palestine following the May war, Weitz and his committee recommended to Ben-Gurion that they be “intimidated without end” until they fled.33 The subsequent expulsion campaigns which took place in the fall of 1948 throughout historic Palestine were thus heavily influenced by Weitz and the transfer committee.

On October 21, a member of the transfer committee told Ben-Gurion that the work of the committee was almost done. Days later, on October 26, the committee submitted its findings and recommendations to Ben-Gurion, which he summarized as follows:

A) The Arabs themselves are guilty of their flight.

B) They should not [be allowed to] return . . .

C) The Arabs who remained inside the state should be treated as equal citizens . . .

D) The Arabs who fled—will be resettled by the Arab governments in Syria, Iraq and Transjordan . . . [and] Lebanon . . .34

The various secret and public transfer plans and committees which characterized Zionist ideology and practice throughout the 1930s and 1940s, and following the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, indicate the extent to which the transfer and resettlement of Palestinian Arabs were fundamental to Zionist strategy. Indeed, Weitz’s two transfer committees, one semiofficial and in operation between May and June 1948, the other official and active from August to November 1948, played significant roles in turning the Palestinian refugee crisis into a fait accompli.35

It can therefore be said that the meticulous Israeli policies of confiscating and expropriating Palestinian land and properties in the years following the establishment of the state—as well as the transfer committees formed thereafter—had their roots in a decades-old vision for a Jewish state permanently depopulated of its native Arab inhabitants.

Seizing Palestinians’ Financial Assets and Properties

Financial assets

As shown by the Nammar family story, the new Israeli state moved swiftly to expropriate the properties and financial assets of the exiled Palestinians. On June 12, 1948, not even a month after the British Mandate had ended and the state had been declared and only one day after the first ceasefire took effect on June 11, the government of the new State of Israel “ordered all commercial banks operating within its territory to ‘freeze the accounts of all their Arab customers and to stop all transactions on Arab accounts.’”36

The banks, which were operating without protection in a field where armed forces roamed freely, were left little choice but to comply:

The Israeli government gave the banks one month to comply with this order and threatened to revoke the licenses of all banks found to be in non-compliance. By the end of December 1948, every bank operating in what had become Israel had obeyed the order, and thus, barely six months after the creation of the state of Israel, all Arab Palestinians, almost all of whom were already homeless and scattered in refugee camps throughout the Arab world, had lost access to the money and valuables which they had deposited in their banks for safekeeping.37

In early June 1948, a Ministerial Abandoned Property Committee was established and tasked with setting policy on abandoned property; Ben-Gurion was its head. On June 30, 1948, Israel created the Abandoned Areas Ordinance,38 giving it the broad power and authority to declare any conquered or surrendered or deserted or even partially deserted area as abandoned, extend law over it, confiscate it, and or issue orders about its disposition.39 Once a property was declared abandoned, the minister of finance was authorized to decide what to do with it. Bank accounts, of course, were one of many forms of property. In early August 1948, the government declared West Jerusalem to be “a territory of the State of Israel.”40

On December 2, 1948, Israel passed the Emergency Regulations on the Property of Absentees. These made the earlier freeze on bank accounts legal under Israeli law, and the banks were required under international law to respect the laws of the countries where they operate. For any bank officers who expressed concern, the Israeli government assured them that this would be a temporary state of affairs.41 For reassurance, the Israelis recalled that the British had frozen the assets and property of all citizens of Axis countries in Palestine during World War II, also using emergency regulations.

However, the reassurance was short-lived as the parallel stopped there. Unlike the British, who had unfrozen and returned all assets when the war was over, Israel moved to take possession of them. In February 1949, Israel created a new entity, the Custodian for Absentee Property, and granted it the authority to define all Arabs displaced during the war as “absentee,” regardless of whether or not they returned. This term applied to hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs, thereby allowing the Israeli government to expropriate their properties, rendering them state property. It then prohibited selling or leasing the land for more than five years42 and ordered the country’s two largest banks, Barclays and the Ottoman Bank, to hand over the funds held in all Arab accounts. By the spring of 1949, this had been done, and Palestinian bank account holders never saw their money again.

On top of this, the British Treasury summarily announced that, as of May 14, 1948, the Palestinian pound, the only legal tender in the country since 1922, would no longer be a legal currency, without saying what would replace it. By March 1948, this meant that the Palestinian pound could not be converted into any other foreign currency. As a result, Palestinians fleeing the country not only could not access their bank accounts, they also could not use any cash they might have managed to carry.43

Property

In terms of property, the war resulted in a radical demographic shift in ownership. According to the 1947 UN Partition Plan, Palestinian individuals owned 40 percent of the properties of the New City before the war, compared to 26 percent owned individually by Jews. Religious institutions—primarily the Greek Orthodox Church—and the British Mandate owned the remainder. Following the war, all the properties of the Palestinian owners were confiscated in what Henry Cattan, famed Palestinian lawyer from the New City, calls one of the “greatest mass robberies in the history of Palestine.”44

These properties were promptly placed under the management of the newly established Israeli Custodian of Abandoned (and later Absentee) Property. The custodian administered and redistributed the property to any prospective Jewish buyer. As Habash and Rempel explain:

In other words, Palestinian Arab refugee property controlled by the state of Israel was expropriated in order to transfer its tenure from Arab to Jewish ownership, even though the 1947 Partition Plan expressly stated that no land owned by Arabs in the Jewish State was to be expropriated except for public purposes.45

More specifically, by the end of the war:

[a] total of 16,324 sq. km out of a total area of 26,320 sq. km were abandoned Arab lands. This included approximately 280 sq. km of rural land in the Jerusalem sub-district and over 7 sq. km in urban Jerusalem lands or combined about 18 percent of the Jerusalem sub-district. Jewish-owned land in the area of the sub-district occupied by Israel amounted to 26 sq. km. The remainder of the sub-district which totaled 1,570 sq. km fell under Jordanian control.46

The value of the confiscated Palestinian lands was estimated to be at “100,383,784 Palestinian pounds or 280 million dollars at the dollar-pound exchange rate in 1951. This was divided into 70 million pounds in rural property with the remainder as urban property.”47 It is further estimated that, “in total, these lands were assessed at 9,250,000 Palestinian pounds,” excluding the 21,570,000 Palestinian pounds in movable property that was confiscated by the Israeli state.48

In 1956, the League of Arab States evaluated the value of lost Palestinian refugee properties in Jerusalem:

The total value of the loss in refugee homes . . . would be 2,393,450 pounds sterling in 1948 prices. The League also determined that refugee losses included some 10,000 shops and commercial premises valued at 175 pounds sterling per year. A simple calculation . . . would set the value of Jerusalem losses in shops and commercial premises at around 120,000 pounds sterling.49

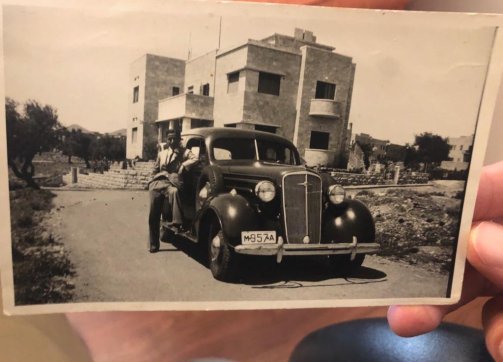

Judaizing the New City

By February 1949, Israel de facto annexed West Jerusalem and it subsequently began transferring its governmental offices there and settling Jewish immigrants in what it labeled as “absentee” Arab properties. The government insisted that this move was not motivated “by a desire to create new political facts.”50 However, throughout 1949 and the 1950s, the Israeli government took several steps to create new demographic facts on the ground which thoroughly Judaized the New City, thus effacing any trace of its Palestinian origins.

In early 1949, it established Amidar, a state-owned public housing company, funded largely by the Jewish Agency for Israel, the Jewish National Fund, and the Israeli government. Amidar was tasked with providing subsidized and rent-controlled housing, primarily for lower-income Jewish families. The settlement of Jews in Arab properties began as early as February 1949, and in order to accommodate the large numbers of Jews being settled in Palestinian homes, many properties were divided into smaller units. In March 1949, for example, Amidar oversaw the division of the famous Sakakini home in Qatamon into two separate floors. And that same month, the office of the Custodian of Absentee Property rented the first floor to the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO), which subsequently ran a nursery there. In April, the second floor was rented to a Jewish family from the Old City.

The government then passed the Emergency Regulations (Security Zones) Law, which designated certain areas as “security zones” in order to ban anyone from permanently living in or entering these zones. The zones were often sold to the Jewish National Fund, and the regulations remained in place until 1972.51

To legitimize its hold on Arab properties, Israel enacted the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law.52 This law stipulated that any person who “was a legal owner of any property situated in the area of Israel or enjoyed or held it, whether himself or through another,” between November 29, 1947, and May 19, 1948, and who has left Palestine before September 1, 1948, would be considered an “absentee.”53 According to the Law and Administration Ordinance, all property belonging to an absentee would be appropriated by the Custodian of Absentee Property, who was then authorized to decide whether to lease, maintain, or sell it.54

Israel also established the Development Authority in 1950 to serve as a major actor in land allocation. According to the Absentees’ Property Law of March 1950 (Clause 19) and the Development Authority (Transfer of Property) Law of July 1950, the Custodian of Absentee Property was now given the authority to sell properties to the Development Authority.55 The goal was to turn over properties to the Development Authority in order to codify the expropriation of Arab lands by the Jewish state as a permanent condition, whereas it had been temporary in the hands of the Custodian of Absentee Property.

Three years later, in March 1953, Israel passed the Land Acquisition (Validation of Acts and Compensation) Law, enabling the selling of all properties under the Custodian of Absentee Property to the Development Authority. The law applied to “immovable property that 1) was not in its owner’s possession on 1 April 1952; 2) had been used for essential development, settlement and security between 14 May 1948 and 1 April 1952; 3) was still needed for these purposes.”56 As a result of this law, the Custodian of Absentee Property sold the Sakakini house to the Development Authority, officially stripping Khalil Sakakini of his ownership of the house. The Development Authority thus became the new formal owner of the house, and it could sell it to a third party. Moreover, through this law, the Finance Ministry bought and nationalized about 1.2 million dunams.

As a final step, in 1958, Israel passed the Prescription Law, nullifying any Palestinian claims to properties protected under the 1858 Ottoman Land Code, which was upheld by British Mandate authorities. The law enabled Israel to claim as “state lands” any property where Palestinians still remained and where they could assert their ownership over the land under the Ottoman Land Code.57 And although the government passed the 1960 Basic Law: Israel Lands, forbidding the sale or transfer of public lands, including those held by the Development Authority, the Development Authority continued to do so throughout the 20th century. Once the Development Authority sold property to a third-party individual, the buyer was subsequently protected from the 1960 law due to ownership rights. This was considered the final phase of expropriating Palestinian Arab property.58

The homes’ new occupants

The homes of Palestinian Arabs in what became West Jerusalem were typically occupied by wealthier Ashkenazi Jews.59 In his book Jerusalem Neighborhoods: Talbiyeh, Qatamon, and the Greek Colony, David Kroyanker points out that many of the Israelis who took over the Arab houses in West Jerusalem neighborhoods were and remain professionals—lecturers, researchers, historians, writers, lawyers, doctors, judges, senior government officials, and others.60

Among the most prominent Jewish residents of Arab homes in the New City is the philosopher Martin Buber,61 who had previously leased an apartment in the Said family home in Talbiyya during the mandate period until 1942.62 Other prominent figures include the historian of the Crusades Yehoshua Braver, the writer Haim Gori, and the president of the Jewish Congress Nahum Goldman.63

The Said house faced a similar fate to Sakakinis’. In the winter of 1947, anticipating the imminent war, Wadie, Edward Said’s father, went to Cairo with his family where he had established a branch of the family business years prior. After the 1948 War, the house was confiscated by the new Israeli state and declared absentee property. During decades of ownership by Amidar, it rented the house to different organizations, including the International Christian Embassy, a right-wing evangelical organization established in 1980 to show support for the Zionist state. In the early 2000s, Amidar sold the home to private Israeli American real estate developers, two brothers who remodeled it and turned it into luxury condominium apartments, rented mostly to vacationing Jewish American families.64

The Terra Sancta College, which straddles the border between the neighborhoods of Talbiyya and Rehavia, was closed with the escalations of the clashes during the 1948 War. During the first years after the war, the college was used as the headquarters of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.65

Talbiyya was very popular among Hebrew University professors after the Nakba, due to its proximity to the Terra Sancta building. The university ran the Faculty of Humanities and part of the Science Department in the Terra Sancta building until 1999.66

As another example, the house of the Khoury family in Talbiyya was built in 1923. It was a one-story house designed according to the traditional layout of the Liwan house style, featuring a central room with living rooms on both sides. After the war, the house was declared absentee property and was sold to the late director general of the foreign ministry Walter Eytan.67

The home of the late Palestinian businessman Constantine Salameh, which was built in Talbiyya in 1930, is now used as the headquarters of the Belgian Consulate; and the square that used to be called after Constantine was renamed “Orde Wingate Square.”68 In the early 1930s, the British RAF commander in Palestine resided in one of Salameh’s houses. After the war, the late Israeli minister of education Zakman Shazar lived there until he was moved to the presidential residence in Rehavia in 1963.69

To this day, few of West Jerusalem’s exiled original inhabitants have been able to return to see their homes. None, certainly, have actually reclaimed ownership of their homes and moved back in. Those who have been able to visit Jerusalem as tourists carrying foreign passports have merely been able to stand outside them, sometimes meeting their current occupiers at the front doors, and in these cases, invariably walking away disheartened and devastated.

Ghada Karmi’s account was a rare instance of someone who was able to return to her old family home in Qatamon on August 23, 1991, at age 51, after an absence of 43 years. Karmi returned to the neighborhood with her daughter, Salma. In an interview with al-Ittihad newspaper, Karmi described her return. The authors of the article explain that, during the visit, Karmi “did not grasp what was happening around her. She didn’t believe what she saw. She stopped knowing whether she was shedding tears or wiping them.”70 The article went on to depict her journey from London to Jerusalem, “carrying her daughter with her to the Jerusalem neighborhood of Qatamon looking for her home, her yard, and her childhood memory.71

Karmi tells the interviewer, “I had never imagined that seeing Qatamon and Palestine closely would surprise me that much, since no trace [of the country as it was] is left.”72

Mona Hajjar Halaby was also able to return to her mother’s family home in Lower Baq‘a. She was able to do so with the help of an Israeli Jew who concealed her identity upon meeting the occupants of the home. In her memoir, she describes entering the home and meeting the Jewish occupants. She and Yosef, her Jewish friend, were given a tour of the house by the occupant, an Israeli Jewish woman of Tunisian descent named Lea who had been living in the US with her Jewish American husband before deciding to permanently move to Jerusalem 10 years prior.73

Forced to remain silent about her true identity, Halaby describes how she felt as though she were “a guest passing through my own mother’s house.”74 During the visit, Halaby noticed an old key hung on the back of the front door. She inquired about it, and Lea replied that it was the original key to the house, which she and her husband decided to keep for aesthetic reasons. Halaby reflected on this sentimental moment:

In the war of 1948, many Palestinians had locked their houses and taken their keys with them when they rushed out the door seeking refuge away from the bombing. And the key has since become the Palestinian symbol of return, of unflinching determination, even if today very few of those keys would fit inside the substituted modern locks. My family’s story was different, however. My uncle Daoud was forcibly dragged out of the house, blindfolded, hands tied behind his back, and dumped in the back of a truck for the long journey to an Israeli labor camp. No one in my family had locked the door. That was why the key was left behind.

I stood silently, my eyes welling up with tears, as I held this cold piece of metal that has such significance to all Palestinians. Holding the key cupped in my hand, I felt my mother’s presence in the house. I desperately wanted to keep that key. I dropped a hint in a whisper, almost as though I were saying it to myself not to Lea, too embarrassed to ask for it. “I wish I could make a duplicate.” But Lea either didn’t hear me or didn’t pick up on my hint. She hung it back behind the door. It was her antique piece of art now. Looking back, I wonder why I didn’t ask for it in a more forceful or deliberate way. It belonged to me after all. Was it too greedy to ask for the key when Lea was kind enough to welcome me into the house? Or was I afraid of a confrontation?75

On her way out of the house, Halaby had a brief exchange with Lea’s husband, who seemed confident in his knowledge of the house’s history. He falsely told Halaby that “it was sold by Arabs in 1948,” ignorant of the fact that it was confiscated after its original inhabitants were driven out.76 And then, Halaby asked Lea whether it would have been “hard for you to buy a house that was taken away from a Palestinian family,” to which Lea replied that “it would have been awful!”77

Halaby’s account is certainly unique in the history of Palestinian refugees returning to Palestine; few have been able to return, and even fewer have set foot in their homes. Today, West Jerusalem is thoroughly Judaized, its Palestinian Arab origins meticulously erased and replaced with streets named after famous Jews and Zionists, many of whom are known historically for “liberating” the city from British rule in 1948.

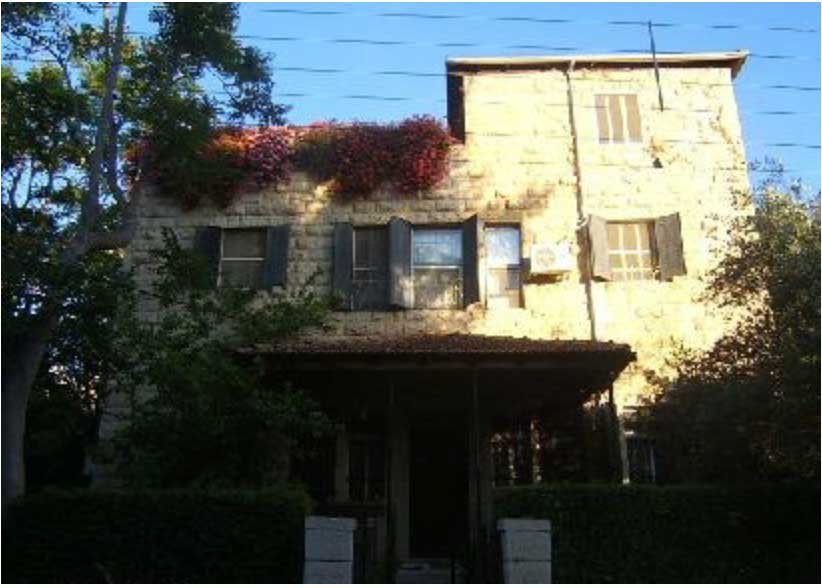

Today, the palatial Palestinian homes that were built in the 1920s and 1930s are featured on Israeli real estate pages promoting the neighborhood with a whitewashed, insipid background story about how it changed hands in 1948—as if by magic—and with not a single question about why the original owners would have ever willingly left such a dream abode.78

Sociologist Hila Zaban has studied this, documenting how the Israeli state preserved the “tangible heritage (architectural structures) . . . separately from intangible heritage (the narrative, memory, and political demands of who produced this architecture).” Zaban shows how in neighborhoods such as al-Baq‘a, Palestinian architecture from before 1948 is commodified as “authentic” for increasing the property value and benefiting Jewish tenants and prospective buyers, but their origins are whitewashed by redesignating them as “Arab,” not “Palestinian.” As Zaban explains, “While the dominant Zionist discourse contests the existence of Palestinians as a people and national movement, it acknowledges the Arabs.”79 She also notes that other scholars have pointed to the fallacy that calling a house an “Arab house” really means “an Arab house that became Israeli Jewish.” They contend that “the neutrality of the term ‘Arab house’ shakes off the responsibility for the oppression and dispossession of both the Palestinians and the Mizrahim [Eastern Jews] who had supposedly merely guarded the houses until their bourgeois redeemers arrive.”80

Israeli real estate agencies advertise most neighborhoods of Jerusalem’s New City this way, thoroughly effacing the city’s Palestinian history and the fact that most of the homes being displayed on the websites were built by Palestinians. For example, “Welcome Home Realty” describes Qatamon as follows:

In the early 1970s, a general process of renewal began in this area, and many of the inhabitants realized their dreams of having stone courtyards, fences, quality porches, tiled roofs and where major renovations were carried out, architectural styles not previously seen in the area.81

The history of the neighborhood prior to the 1970s is missing from the description. Indeed, highlighting the Israeli government’s role in its renewal effectively renders it “dead” prior to the 1970s.

And in the few instances where the company recognizes a neighborhood’s Palestinian origins, it deliberately avoids using the term Palestinian, and never addresses Israel’s systemic process of dispossessing Palestinians and depopulating the New City in 1948. For example, al-Baq‘a is described as follows:

The name Baka was taken directly from the Arabic word meaning “Valley,” which of course is an indication of the topography of the area. It was established in the 1920s when wealthy Muslim and Christians families decided to build homes in that attractive valley—Baka—and beautiful private homes they were.

The Israeli professional middle-class soon spotted the potential of this neighborhood and particularly during the 1970s began en masse to settle in Baka, renovating and updating those magnificence homes, surrounded as they were, by gardens and trees. If you didn’t know it, you could be somewhere in Europe.82

Certainly, naming Palestinians as Muslims and Christians, and not as Palestinians or even Arabs, fits with the larger narrative of Israel’s erasure of Palestinian Jerusalem. And for prospective renters and buyers, admiring this neighborhood’s historic magnificence while enjoying its renovations, which are reminiscent of “somewhere in Europe,” yields a narrative of a historical and modernizing state committed to the development of its cities’ real estate.

In other words, if it were not for the Israeli state, these neighborhoods would somehow remain abandoned and undeveloped, frozen in a dead history. Indeed, the real estate company describes Talbiyya as follows:

The neighborhood of Talbieh is one of the most beautiful in the city . . . In the neighborhood it is possible to see a rich variety of buildings from the Mandate period, as well as authentic Arab houses that have been expanded or have had additions made to their original structures. In Talbieh, many houses have been declared historical preservations.83

Exoticizing Arab homes as “authentic” further feeds into the orientalist imaginations of prospective Jewish buyers dreaming of a modern life in an ancient city. To this day, most Israeli Jews in West Jerusalem remain ignorant of the brutal realities of the 1948 War in Jerusalem’s New City, and of the dispossession and forced exile of thousands of Palestinian Arabs from their homes, the homes in which they now reside. For Palestinian Jerusalemites, however, wherever they may reside, and for Palestinians generally, the wounds of the trauma inflicted during the birth of “West Jerusalem” (as well as of the Nakba generally) are alive and reverberating to this day.

Contributors

Nadim Bawalsa and Kate Rouhana of the Jerusalem Story Team collaborated on the research, writing, and editing for this Backgrounder.

Shahrazad Odeh, formerly with Jerusalem Story, worked on an early version of this Backgrounder.

Notes

Salim Tamari, “The City and Its Rural Hinterland,” in Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighbourhoods and Their Fate in the War, ed. Salim Tamari (Jerusalem and Bethlehem: Institute of Palestine Studies and Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, 2002), 79. See Palestinian Villages Depopulated in 1948 for more up-to-date information reflecting the names of two more villages, though excluding their populations. Data collected by Zochrot.

Yehouda Shenhav, “The Palestinian Nakba and the Arab-Jewish Melancholy: An Essay on Sovereignty and Translation,” in Jews and the End of Theory, ed. Shai Ginsburg, Martin Land, and Jonathan Boyarin (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018), 48–64.

Terry Rempel, “Dispossession and Restitution in 1948 Jerusalem,” in Jerusalem 1948, 218. Other sources place the percentage of the remaining Palestinian population at 1 percent, most of whom came from the Palestinian village of Beit Safafa, which was split by the 1949 armistice line. Part of Beit Safafa was absorbed into West Jerusalem. Michael Romann and Alex Weingrod, Living Together Separately: Arabs and Jews in Contemporary Jerusalem (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016; first published 1991), 9n4.

Romann and Weingrod, Living Together Separately, 32.

Michal Korach and Maya Chosen, eds., Jerusalem Facts and Trends 2021 (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, 2021), 19.

David Ben-Gurion, during a speech delivered to the Mapai Council, February 7, 1948, after giving an order two days earlier to settle Jews in the vacated Arab districts of the New City of Jerusalem (later West Jerusalem). As cited in Nathan Krystall, “The Fall of the New City 1947–1950,” in Jerusalem 1948, 94–95. Lifta is an Arab village located northwest of Jerusalem, and Romeima is a formerly multiethnic neighborhood of the New City on the highest hill adjacent to Lifta.

Jacob Nammar, “Remembering Haret al-Nammamreh,” Jerusalem Quarterly 41 (2010): 65.

Nammar, “Remembering,” 61–62.

Zena Tahhan, “The Naksa: How Israel Occupied the Whole of Palestine in 1967,” Al Jazeera, June 4, 2018.

Sreemati Mitter, “A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2014), 106.

Rempel, “Dispossession and Restitution,” 223.

Michael Dumper, Jerusalem Unbound: Geography, History, & the Future of the Holy City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 46.

Nur Masalha, Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882–1948 (Washington, DC: The Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992), 1.

Masalha, Expulsion, 1.

Masahla, Expulsion, 38.

Masahla, Expulsion, 25.

Masahla, Expulsion, 56.

Masahla, Expulsion, 61.

Masahla, Expulsion, 95.

Masahla, Expulsion, 96.

Masahla, Expulsion, 99.

Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2006), 61–62.

Pappe, Ethnic Cleansing, 62.

Rempel, “Dispossession and Restitution,” 210.

Rempel, “Dispossession and Restitution,” 210.

Benny Morris, “Yosef Weitz and the Transfer Committees, 1948-49,” Middle Eastern Studies 55, no. 4 (1986): 522–61, at 531.

Morris, “Yosef Weitz,” 531.

Morris, “Yosef Weitz,” 531–32.

Pappe, Ethnic Cleansing, 63.

Pappe, Ethnic Cleansing, 147.

Masalha, Expulsion, 193.

Pappe, Ethnic Cleansing, 63.

Masalha, Expulsion, 195.

Morris, “Yosef Weitz,” 550.

Morris, “Yosef Weitz,” 554–55.

Mitter, “A History of Money,” 105.

Mitter, “A History of Money,” 105.

Felix Rosenblueth, “Abandoned Areas Ordinance,” June 30, 1948.

Rosenblueth, “Abandoned”; Geremy Forman and Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar, “From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948,” Environmental and Planning D: Society and Space 22 (2004): 813.

Krystall, “The Fall of the New City,” 120.

Mitter, “A History of Money,” 107.

Danna Piroyansky, “From Island to Archipelago: The Sakakini House in Qatamon and Its Shifting Ownerships throughout the Twentieth Century,” Middle Eastern Studies 48, no. 6 (2012): 863.

Mitter, “A History of Money,” 120.

Dalia Habash and Terry Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property in West Jerusalem,” in Jerusalem 1948, 167.

Habash and Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property,” 168.

Habash and Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property,” 173.

Habash and Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property,” 174.

Habash and Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property,” 175.

Habash and Rempel, “Assessing Palestinian Property,” 185.

Zochrot Organization, “al-Quds (Jerusalem),” Zochrot, August 2017.

Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions [COHRE] and BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, Ruling Palestine: A History of the Legally Sanctioned Jewish-Israeli Seizure of Land and Housing in Palestine (Geneva: Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions and BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, 2005), 40.

David Ben-Gurion, Eliezer Kaplan, and Chaim Weizmann, “Absentees’ Property Law,” United Nations, 5710–1950, March 14, 1950.

Ben-Gurion, Kaplan, and Weizmann, “Absentees’ Property Law.”

Usama Halabi, Israel’s Land Laws as a Legal-Political Tool (Bethlehem: Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, 2004).

Piroyansky, “Island,” 865.

Piroyansky, “Island,” 865.

COHRE and BADIL, Ruling Palestine, 44.

Piroyansky, “Island,” 873.

Joel Beinin, “From Urban Cosmopolitanism to ‘Mixed Cities’ to Ethnic Purity,” Jadal, no. 18 (2013).

Wadi‘ ‘Awawada, “West Jerusalem Houses Testify to Their Identity” [in Arabic], Al Jazeera, March 30, 2016.

David Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods: Talbiyeh, Qatamon and the Greek Colony (Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies and Keter, 2002), 36.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 169.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 36.

Nadim Bawalsa, “Teta Nabiha’s,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 84 (2020): 139–49.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 36.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 36.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 146.

Awawada, “West Jerusalem Houses”; Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 66.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 66.

Amal Shihada, “Umm Salma Returned to Qatamon” [in Arabic], al-Ittihad, August 23, 1991.

Shihada, “Umm Salma.”

Shihada, “Umm Salma.”

Mona Hajjar Halaby, In My Mother’s Footsteps: A Palestinian Refugee Returns Home (London: Thread, 2021), 272.

Halaby, In My Mother’s Footsteps, 276.

Halaby, In My Mother’s Footsteps, 277.

Halaby, In My Mother’s Footsteps, 278.

Halaby, In My Mother’s Footsteps, 278.

Jerusalem Real Estate, “Talbiya Jerusalem Real Estate—About the Neighborhood,” 2019.

Hila Zaban, “Preserving ‘the Enemy’s’ Architecture: Preservation and Gentrification in a Formerly Palestinian Jerusalem Neighborhood,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23, no. 10 (2017): 961–76.

Zaban, “Preserving the Enemy’s Architecture.”

Welcome Home Realty, “Neighborhoods,” 2011.

Welcome Home Realty, “Neighborhoods.”

Welcome Home Realty, “Neighborhoods.”