al-Walaja before 1948

Credit:

iStock Photo

al-Walaja: The Ancient Palestinian Village Ghettoized by Proliferating Settlements and the Separation Wall

Snapshot

Al-Walaja is a picturesque rural ancient village located on the high mountain ridge east of Bethlehem and southwest of Jerusalem. Until 1948, it was one of the largest agricultural villages in Palestine. Standing 750 meters above sea level, it overlooked the most central routes that connect the region together and enjoyed vast and fertile land holdings. That reality changed drastically after 1948 and then again after 1967, following a chain of catastrophes that hit the village produced by a relentless Israeli expansionist effort that sought to shrink, fragment, and besiege the village while establishing, building, and expanding Jewish settlements all around it. This case study takes a detailed look at the surreal realities faced by the remnants of al-Walaja, today essentially an open-air prison, which is facing assaults on all levels from a state clearly bent on erasing it.

Located on a hill range 9 km southwest of Jerusalem and 4 km northwest of Bethlehem, the village of al-Walaja has a rich history that dates back to the Canaanites.1 Spanning over 18 km in size until 1948, al-Walaja used to be one of the largest villages in Palestine with a population of more than 1,800 people,2 mostly farming families. In 1944–45, the Arab villagers owned 17,507 dunums of land, of which 8,363 were cultivable.3 By 1948, the village was bustling with life and it was considerably expanding; new stone houses were built to the northeast and southeast; it had several shops and an elementary school, as well as a mosque.4

Agriculture was plentiful, aided by five groups of springs that flowed naturally nearby, creating wells that made it possible to cultivate some crops from rainfall only.5 Indeed, al-Walaja used to be one of the most fertile villages in historic Palestine, with many sources for irrigation, including rivers and more than 20 ancient springs that nourished its soil, cultivating fruits, vegetables, vineyards, and olive trees.6 Indeed, al-Walaja is home to the second oldest olive tree in the world: al-Badawi, which is over 4,000 years old.7

The elevated village rests 750 meters above sea level. It thus overlooks the most central valleys in the region, with the railway tracks built at the end of the 19th century passing through it and connecting it to the rest of the country. Moreover, as the village is located between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, it served an important role in connecting the two city centers, especially following the opening of the railway in the late 19th century. The stop before Jerusalem was located in the neighboring village of Battir (which still exists today). In fact, this strategic geography is what gave the village its name, al-Walaja, which roughly translates to the “opening” or “a place that passes into or through something, often by overcoming resistance.”8

Hence, until 1948, al-Walaja was one of the most accessible villages in Palestine, naturally connected to its surrounding regions and a link between the hilly regions and the coast.

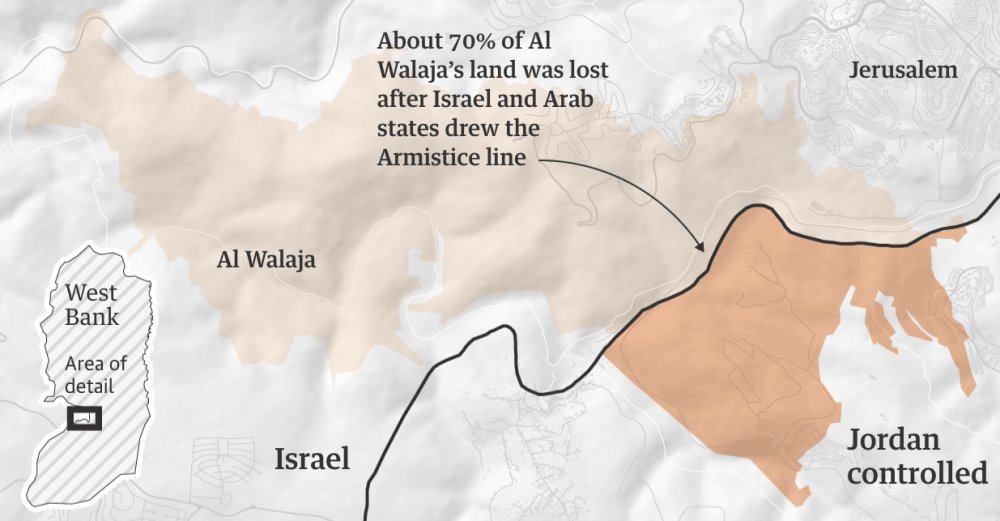

After the 1948 War (1948–67): The First Divide—between East and West

In 1948, the village faced its first Nakba, along with most of historic Palestine. On October 21, 1948, Haganah forces attacked al-Walaja at night and captured it, one of a string of villages captured during Operation Ha-Har to widen the corridor to Jerusalem.9 While this attack was initially repelled, much of the village, including the main built-up parts with about three quarters (70 percent) of the land,10 was later annexed by Israel as part of the armistice agreement of 1949.11 Most of the village was lost, with the majority of its inhabitants expelled and made refugees who then spread across the West Bank, Jordan, and Lebanon. Among them, about 100 were able to remain within the boundaries of al-Walaja by resettling on a hill located on its southeastern ridge, where they established what became known as “al-Walaja al-Jadida” (New Walaja).12 Many lived in caves and shelters built for them by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA).13 As of today, about 3,000 of the descendants of the original villagers live in New Walaja.14

The remaining villagers were left with no access to most of their cultivated lands, which were quickly absorbed into what became Israel. These areas included the springs and natural resources on which they had depended, as well as the homes in which they had lived for generations. Israel destroyed most of these in 1954 to prevent the villagers’ return.15

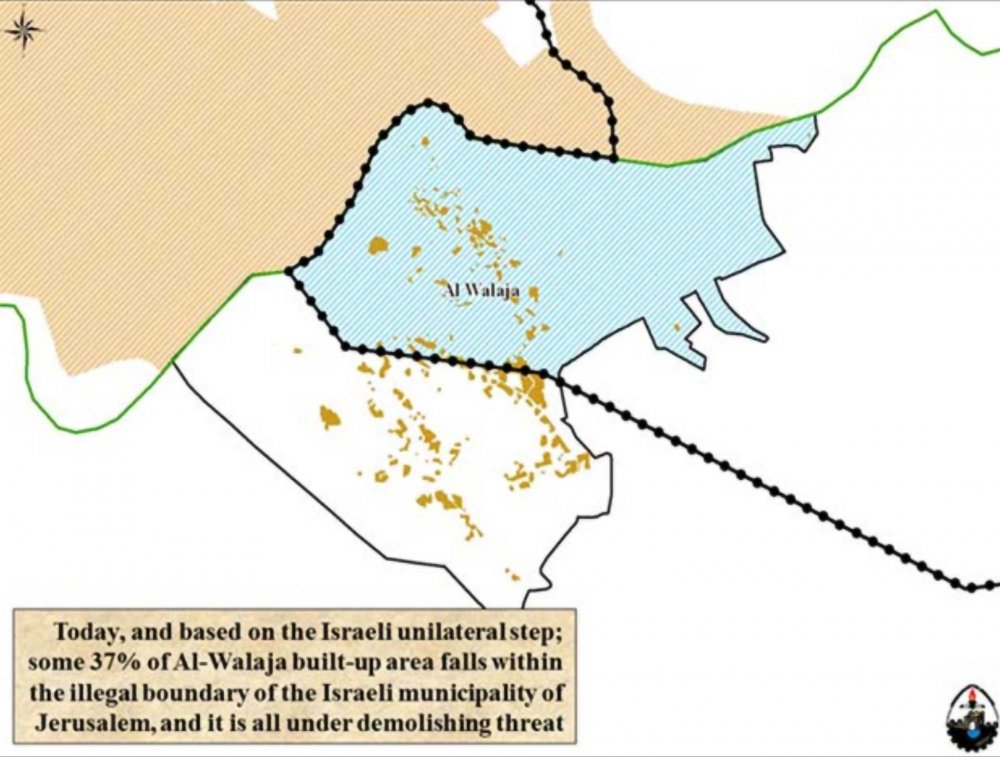

After the 1967 War (1967–95): The Second Divide—between North and South (Inside and Outside of the Israeli Municipal Boundaries)

After the 1967 War, al-Walaja al-Jadida, along with the rest of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), fell under Israeli military occupation, and the village was divided yet again. This time, it was jurisdictionally divided in half. As Israel unilaterally and illegally expanded the Jerusalem city boundaries just after the war (see Where Is Jerusalem?), the northern half of al-Walaja al-Jadida,16 known as the ‘Ayn Jweizeh neighborhood, was incorporated into the expanded Jerusalem municipality.17 At the same time, all of al-Walaja’s residents (within and without the municipal boundaries) remained under Israel’s military administration of the West Bank, meaning that none of its inhabitants were granted legal status as permanent residents—unlike the rest of the residents in other Jerusalem localities incorporated into the newly expanded boundaries18 (see Precarious, Not Permanent: The Status Held by Palestinian Jerusalemites). Rather, these residents were compelled by Israel to carry West Bank IDs—later issued by the Palestinian Authority (PA), even though it had no jurisdiction inside the city boundaries. As well, while ‘Ayn Jweizeh falls within the Israeli municipal boundaries, the Jerusalem municipality did not provide any basic services to the village.19

The legal status of ‘Ayn Jweizeh

The placement of all of al-Walaja al-Jadida, including the part that fell within Israeli municipal boundaries, under military rule enabled Israel to designate the villagers’ properties on the northern side as “Absentee Property.” In 1980, with Israel’s announcement of the annexation of East Jerusalem, including ‘Ayn Jweizeh, Israel started using the 1950 Absentee Property Law to confiscate private property and land in the northern part of the village, which resulted in tens of home demolitions and the displacement of more villagers, who were rendered refugees for the second time. This process continues to this day, with the remaining inhabitants on the northern side of al-Walaja al-Jadida under perpetual threat of expulsion from their homes. Indeed, Israel considers approximately 150 homes in ‘Ayn Jweizeh to be illegally built. Thus, they are under constant threat of demolition.20

Because of this situation, not only is the presence of Palestinian homes and structures in the area deemed illegitimate, but even the residents themselves. Therefore, Israel considers those residents who have PA-issued IDs to be living in their own homes illegally. In addition, despite the fact that the northern side of the village’s border with the municipality of Jerusalem is not physically blocked by the Separation Wall, holders of PA IDs are prohibited from crossing over the city boundaries without military-issued entry permits. If they do dare enter, Israeli soldiers sometimes raid the village to arrest them.21

To confront this impossible situation, the inhabitants of ‘Ayn Jweizeh appealed to the Israeli Supreme Court twice to be considered part of the West Bank: first, in 1989, and then again in 2003. However, both appeals were rejected.22 Indeed, in 2004, 80 Palestinian villagers were arrested for their mere presence next to their homes that fall within Israel’s Jerusalem municipal boundaries.23 And so, in the same year, villagers requested to do the opposite—i.e., to legalize the residential status of 280 persons living in ‘Ayn Jweizeh as Israeli permanent residents. This request was also rejected in 2008.24 The residents of ‘Ayn Jweizeh were thus condemned to live in legal limbo, under the absurd status of being illegal occupants of in their own homes.

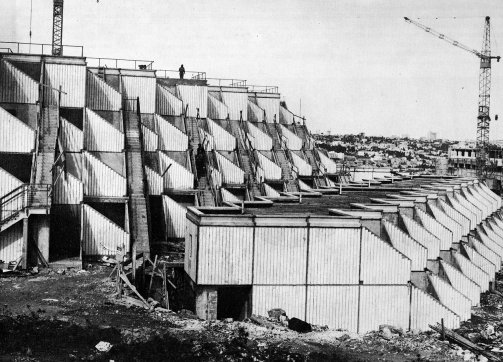

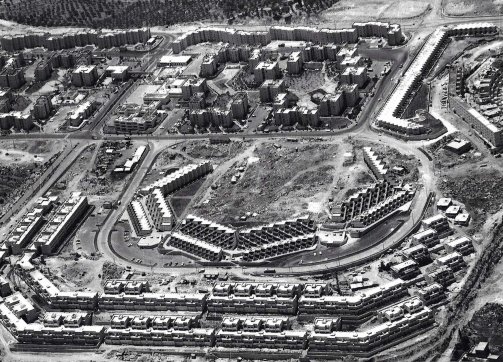

The beginning of settlement construction and expansion around al-Walaja

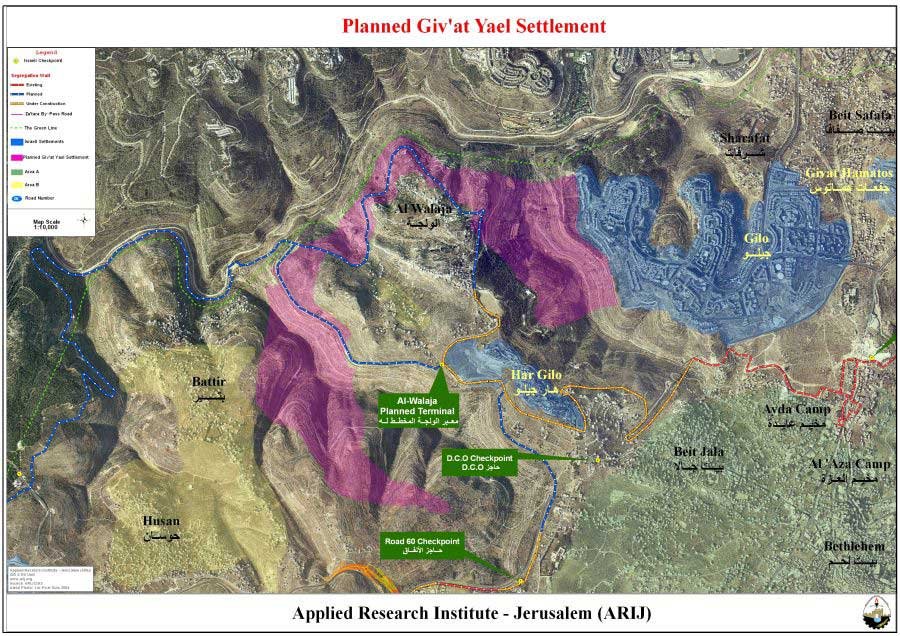

In the early 1970s, following Israel’s occupation of the West Bank in 1967, Palestinian lands in and around al-Walaja were confiscated for the establishment of two settlements, Gilo and Har Gilo (see Settlements). These settlements were built on confiscated Palestinian land, including 137 dunums from the eastern and southeastern parts of al-Walaja.

Gilo is a major urban settlement founded within the official municipal boundaries of Jerusalem (as expanded in 1967), while Har Gilo is a rural settlement, built right on the West Bank side of the municipal boundary. Given each settlement’s location vis-à-vis the city boundaries, each is administered by a different Israeli authority (the Jerusalem municipality and the Military Civil Administration). Nonetheless, they were established as part of one network of Israeli settlements to expand and form a link between the Gush Etzion settlement bloc south of Jerusalem with those within the expanded municipal boundaries, as part of the “Greater Jerusalem” vision (see Settlements and Israel’s Vision of a Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem).

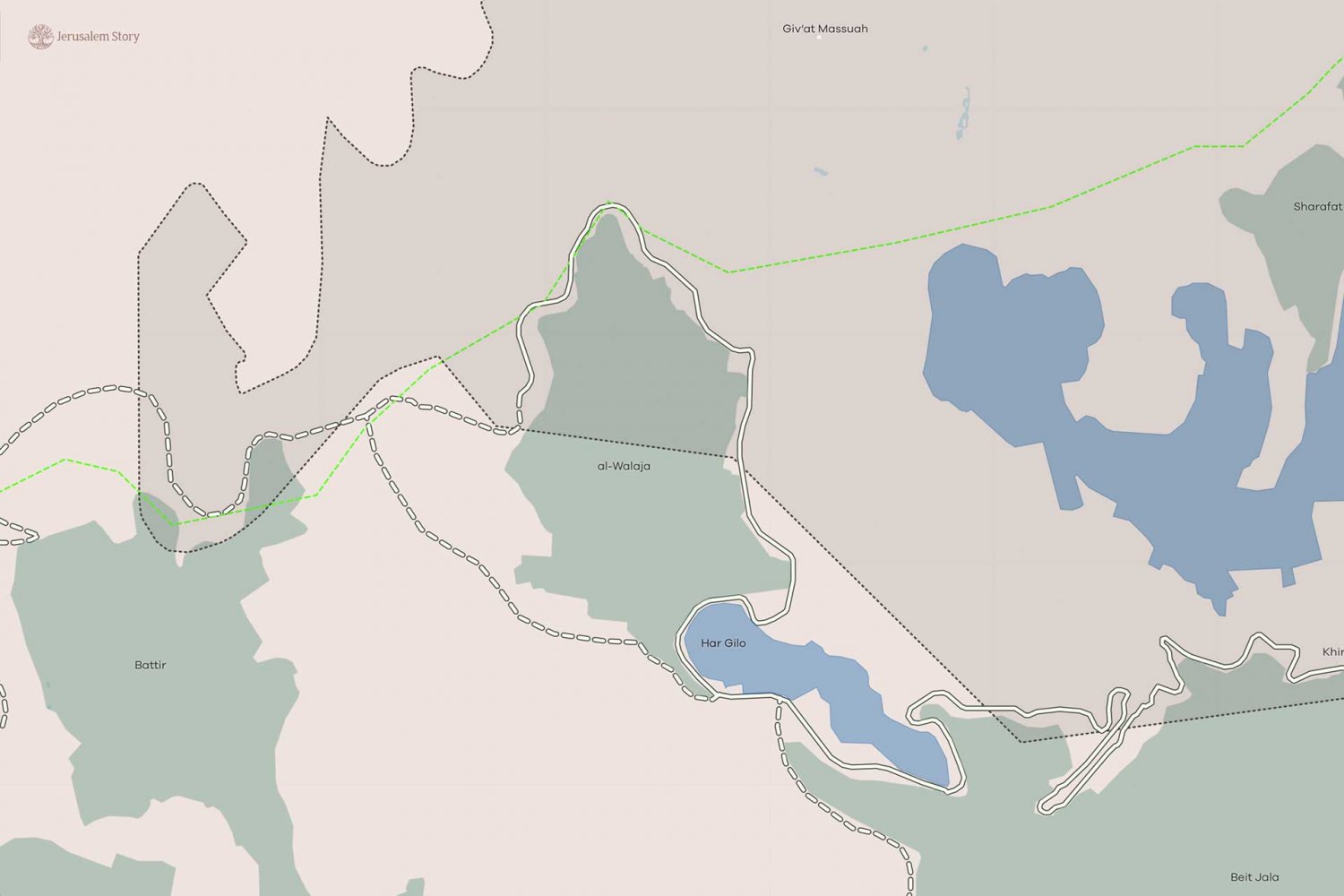

With the Green Line to its west, expanded municipal boundaries to its north, and settlements encroaching to its east and southeast, the small village is increasingly blocked from any kind of natural growth, which contributes to its progressive asphyxiation and ghettoization.25

Post-Oslo (1995): The Third Divide—between the Village Core and the Surroundings (Areas B and C)

Another layer of fragmentation imposed by Israel followed the 1995 Oslo II Agreement, whereby the majority of the village lands (about 97.4 percent) was designated as Area C, and only 2.6 percent as Area B, consisting of the core built-up area in the village, with no lands designated as Area A.26 In Area C, which includes “all the agricultural lands, the open spaces, and all the lands suitable for future expansion,”27 Palestinians are prevented from building anything or benefiting from the land in any way without the permission of the Israeli Civil Administration, which is almost impossible to obtain.28

This gave Israel the authority to obstruct construction by delaying or denying building permits29 and to demolish any and all kinds of Palestinian structures, including homes, roads, and farming infrastructure.30 And without building permits, residents of al-Walaja are left with no choice but to build essential educational, health, agricultural, and residential structures without authorization. This exposes them to the risk of demolition.

Prohibition on Palestinian urban development and settlement expansion

The al-Walaja local council, which was established post-Oslo in 1996 in Area B, was squeezed into a tiny area that is densely built up. The council has limited control over the village, and despite efforts at developing the village, the council is generally prohibited from providing the community with much-needed services, including the paving and repair and maintenance of roads and other public paved surfaces, most of which lie in Area C.31 In addition, the ambiguous administrative status of the territory (i.e., that it is administered by both the Jerusalem Municipality and the Civil Administration in Gush Etzion) complicates the council’s procedures in creating development plans to be approved by any of the authorities administering the divided area. When infrastructure is improved, often with international aid, the Israeli Civil Administration not uncommonly demolishes the improvements on the basis that they were built without permits.32

Israel’s policy on prohibiting development for Palestinian villagers of al-Walaja operates alongside the systematic demolitions that keep the land clear for future Israeli Jewish settlement expansion. Essentially, Israel put in place a planning regime that completely prohibits any kind of growth for the Palestinian village, while allowing settlements both within and outside the municipal boundaries to freely expand on the village’s confiscated land.

Beyond prohibiting development, Israel continues to suppress existing development in the village. Between 1985 and 2006, Israel issued about 90 demolition orders against Palestinian homes in al-Walaja, and implemented 45 such orders, 30 of which were in ‘Ayn Jweizeh and 15 in the rest of the occupied West Bank.33 In the early 2000s, when Israel began building the Separation Wall, the checkpoints, and the bypass roads in this area, home demolition campaigns intensified in al-Walaja and across the West Bank. Using military orders, Israel confiscated Palestinian land and justified the demolition of Palestinian property by citing “military purposes.” The campaign went through a minor freeze after locals petitioned against it in June 2006 on the basis that the municipality had not provided any zoning plans. After the residents prepared their own plan in 2008, which would have allowed homes already built to be approved for permits along with future planned homes, the district board at first refused to even hear the plan. Only when compelled by the residents’ petition to the Supreme Court did it issue a ruling, in 2009, rejecting the proposed plan. Home demolitions continued in 2010 and 2011 despite numerous legal battles.34

After 2016, Israeli settlements surrounding the village began to expand again, and new settlement plans were being approved. A new law called the Kaminitz Law was passed in 2017, removing legal oversight from the demolition orders and empowering lower-level civil authorities to issue demolition orders and levy fines.35 Accordingly, between 2016 and 2019, 30 structures were demolished in the village, displacing about 39 Palestinians and affecting 121 others.36

Every single development plan prepared and proposed by the residents of ‘Ayn Jweizeh has been rejected by the Israeli municipality, preventing the upkeep of the village.

When the Jerusalem district committee finally agreed to review the residents’ plan in 2021 (after 15 years of stonewalling), it outright rejected it and instead declared the area “an agricultural area,” meaning that “no building would ever be permitted.”37 As a result, as of 2021, in ‘Ayn Jweizeh, 38 homes face pending demolition orders, subjecting some 3,000 Palestinian residents to the risk of forcible expulsion.38

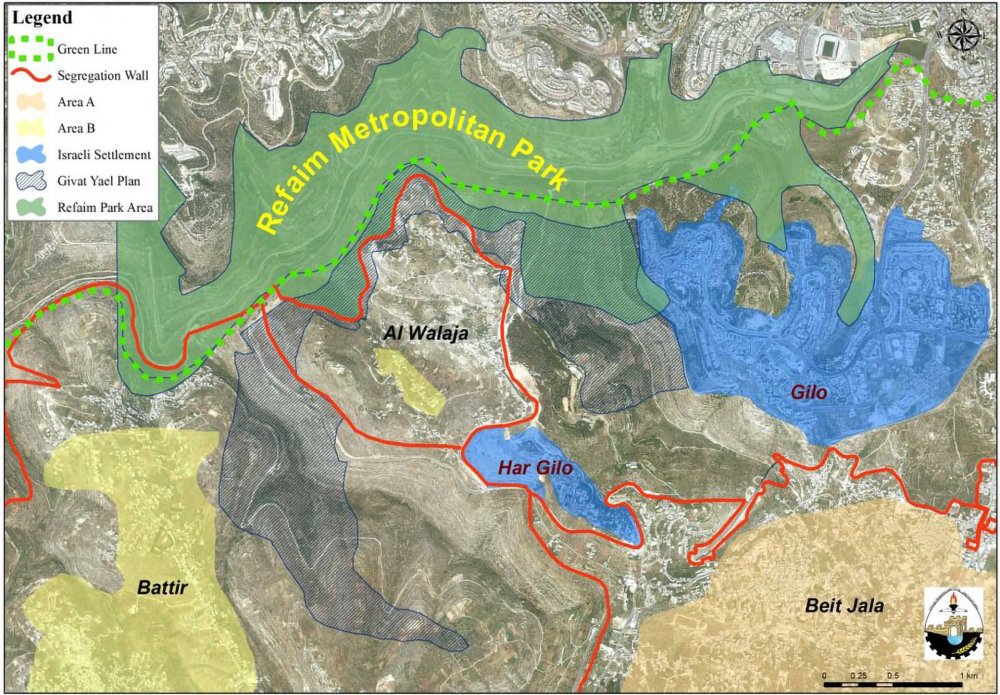

The municipality usually justifies these rejections on the pretext that the plans do not align with the Jerusalem master plans that define al-Walaja as “open space.” Meanwhile, the planning board and the Civil Administration approved “a massive construction plan designated for Jews on all the surrounding hills,”39 on lands confiscated from al-Walaja—including parks that would be exclusively accessible to Jewish settlers under the pretense of protecting the environment. Moreover, residents who protested the installation of the Separation Wall based their petition on the fact that the expansion of the wall ate away at the village’s green space, compounding disastrous environmental damage. Israel denied these claims and built the wall.

As Ir Amim and Bimkom jointly put it:

The designation of areas as national parks, nature reserves, and/or green spaces is a common practice of Israeli authorities in East Jerusalem to suppress Palestinian planning and residential development while allowing for the seizure of their lands to serve Israeli interests. Although the planning committee dismissed the village’s outline plan for the purpose of ostensibly promoting nature conservation, plans for Israeli settlement construction in the same area on lands confiscated from al-Walajeh have all been advanced. This includes expansion of the Gilo neighborhood/settlement (to the east of the village), the al-Walajeh Bypass Road and the new settlement of Har Gilo West. Not only does this reveal the baseless nature of the committee’s claims concerning environmental considerations, but also underscores the rampant planning and housing discrimination leveled against Palestinians in Jerusalem. Likewise, the committee’s citation that the area’s traditional and historical agricultural assets must be preserved explicitly overlooks the village’s essential role in this centuries-old preservation. Continued cultivation of the land and conservation of the surrounding landscape is inextricably tied to the existence of the village and the close proximity of their homes to their agricultural lands.40

Ultimately, Israel uses the “environment,” as it does “security,” as a means to justify the suppression of Palestinian development and collective existence while advancing Israeli development and growth through settlements and other urban planning measures. As attorney and al-Walaja resident Ibrahim al-Araj asked: “When they build Har Gilo, it doesn’t affect nature, but only when we [in al-Walaja] build does it affect nature?” Incredulous, he declared: “It’s blatant racism.”41 Indeed, the Israeli settlements of Gilo and Har Gilo continually expand on the same village lands on which the al-Walaja council was forbidden to develop out of purported concern for the environment. Moreover, Israel plans to connect these settlements to one another, as well as to the west of al-Walaja, with the Separation Wall encompassing them.42

The Separation Wall: “The Second Nakba”

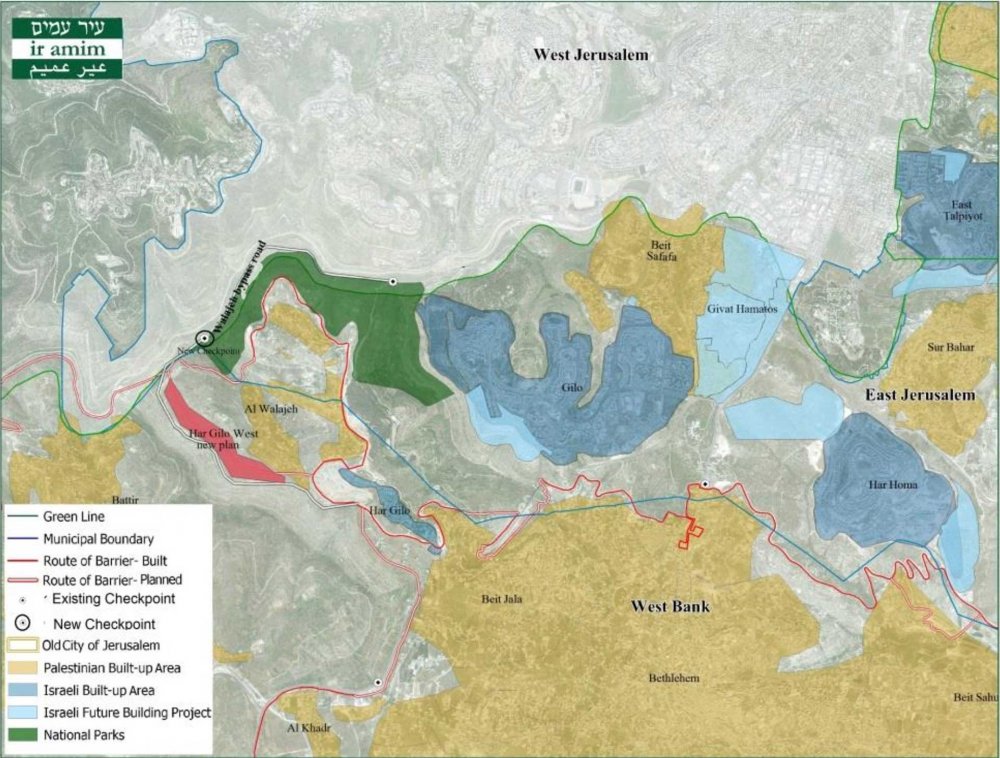

Following the failure of the Oslo Accords in the late 1990s and the Second Intifada, which erupted in September 2000, Israel’s efforts to create geopolitical “facts on the ground” that would guarantee Israeli permanent sovereignty over Jerusalem and its surroundings intensified. That is, in the early 2000s, Israel intensified its implementation of a closure policy aimed at restricting the movement of Palestinians holding PA-issued IDs within and around Jerusalem, and prohibiting their access to the city (see Jerusalem: A Closed City) This was accompanied by the construction of the Separation Wall soon after, which, along with a system of bypass roads and checkpoints, completely enveloped and connected the expanding Israeli settlements in and around Jerusalem (see Jerusalem Envelope). The wall also contributed to further fragmenting, ghettoizing, and strangulating Palestinian villages and neighborhoods in the city and region (see The Separation Wall).

This process was especially intensive in the southern Jerusalem region, where the Separation Wall’s construction entailed the confiscation and de facto annexation of swathes of Palestinian land to further disconnect the Jerusalem–Bethlehem metropolitan continuum. The process simultaneously ensured the expansion of settlements while further solidifying the spatial, territorial, and transportational connectivity between them.

The strategic location of al-Walaja between East Jerusalem (to its north) and the Gush Etzion settlement cluster (to its south) makes the village an impediment to Israel’s plans in the area. As a result, al-Walaja has become a target of Israeli politicians and planners working to establish a Greater Jewish Jerusalem (see Israel’s Vision of a Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem).43 These developments have radically disrupted life in the village yet again, which prompted local resident Salah Abu Ali and others to call this “the second Nakba.” As Abu Ali put it: “We lost all our land in the first Nakba. Now, we have the second Nakba which is the Separation Wall and the building of the settlements.”44

Encircling and Caging al-Walaja

Construction of the Separation Wall around al-Walaja began in 2007 according to plans that went through various revisions following multiple petitions submitted to the High Court by the villagers.45 While the wall was initially supposed to split the northern and southern neighborhoods of al-Walaja, in correlation with the Israeli municipal boundaries expanded in 1967 (see “The Second Divide,” above), the route of the wall ended up extending over 7.2 km, tightly encircling the whole village (both ‘Ayn Jweizeh and the southern part of al-Walaja) and slicing off more of its land, including vast agricultural areas, forests, and open spaces.46

The route of the wall isolated the village from all its neighboring communities, rendering it a ghetto. Indeed, the route completely besieged the village, prohibiting any kind of natural growth in any direction. Importantly, the wall’s route severed al-Walaja’s historic territorial connection with neighboring Palestinian communities, such as Battir to the southwest, and gave it only one exit at its southern end to Beit Jala.

Strangulating al-Walaja

The wall’s route further reduced the boundaries of the village, effectively confiscating most of the surrounding farmlands and the natural resources that remained. This continues to seriously damage their livelihoods.47 Indeed, the construction of the wall came at the cost of uprooting or damaging hundreds of trees, upon which al-Walaja’s families have historically depended, including olive trees.48 To be sure, the Separation Wall severed al-Walaja from between 30 to 35 percent of its remaining lands and natural resources:49

- Agricultural: Up to 115 dunums, comprising 32 percent of the village’s total heterogeneous cultivable agricultural area (385 dunums)

- Forests: More than 180 dunums of forest amounting to 96 percent of the village’s total forests

- Open space: 735 dunums, comprising 89 percent of the total open spaces of al-Walaja (821 dunums)50

The wall left just 11 percent of pre-1948 village land and 46 percent of post-1948 land readily accessible to the villagers.51 Simultaneously, the planning of the wall was accompanied by many Israeli military plans between 2003 and 2007, plans that confiscated even more land in order to expand the system of checkpoints and bypass roads that function alongside the wall to connect and envelop the surrounding Israeli settlements while caging in the Palestinian village.

Expansion of Gilo and Har Gilo

Despite protests, petitions, and legal battles, as well as a short halt in the construction of the wall and home demolitions in the village, after 2010, Israel went ahead with its policies of isolating al-Walaja. In fact, in 2011, Palestinians submitted a petition protesting the construction of the wall, citing the damage it would cause to the village’s farmlands. The Israeli authorities rejected the petition, stipulating that “The injury done to the petitioners is proportional to the security benefit.”52

The Separation Wall’s route was intended to serve the enveloping of settlements into Jerusalem, as well as their territorial expansion and interconnection, solidifying the link between the settlements in the southern Gush Etzion bloc and those in East Jerusalem. Indeed, the plans to expand settlements around al-Walaja and the plans for the route of the Separation Wall were redrawn in sequence. That is, at the same time as the wall was encroaching on village land, it completely encompassed Gilo and Har Gilo, folding them in to the Jerusalem side, allowing for their expansion.53 While Har Gilo lies outside the 1967 Israeli-imposed municipality boundaries, it was de facto annexed and linked to the inner settlement ring (see Settlements). The wall’s route around Gilo de facto annexed the agricultural land of al-Walaja from the north, ensuring the settlement was allocated more space for future expansion.54

The 2012 planned expansion of Gilo was approved in 2015 after a nine-year legal battle between Palestinian landowners, the Beit Jala municipality, and the Salesian Monastery in the Cremisan Valley. This expansion facilitated the creation of territorial continuity between Gilo and Har Gilo, and even the incorporation of parts of the Cremisan Valley—a vital source of income for Palestinians in Beit Jala and of recreational space for al-Walaja residents—into “public space” for Jewish settlers.55

These expansion plans affect Palestinian lives directly and irreparably. For example, as part of the efforts to connect the Gush Etzion settlement bloc to the Jerusalem metropolitan core, the bypass road and Separation Wall tore through the lands of the Hajajla family in al-Walaja. The land, on which the family depended for its livelihood, was confiscated in 2011 despite appeals to the military court, and without any compensation.

For Israel, working to establish a Greater Jewish Jerusalem, the gifts that made al-Walaja one of the most important villages in Palestine, created by its geography, nature, and the centuries of care for the land, are precisely what made it a target of colonial territorial control. Since 1967, Israel has sought to create a permanent territorial linkage between the settlements it built in the East Jerusalem region to those in the south West Bank region, including the Gush Etzion bloc to the east of Bethlehem. The density of the Palestinian population right to the south of Jerusalem did not provide Israel with the possibility to cut through with a corridor. On the other hand, the spaciousness and height of al-Walaja and its close proximity to the Green Line right between the Gush Etzion settlement bloc and the illegally Israeli defined Jerusalem municipality boundaries made al-Walaja an irresistible target.

Following its first catastrophe in 1948, where the village lost most of its population and more than two thirds of its land, after the occupation of the rest the village in 1967, the village suffered continuous blows that radically uprooted their lives and livelihoods. Ever since 1967, the “facts on the ground” of settlement planning, construction, and expansion around al-Walaja reveal an underlying logic and a consistent pattern of dispossessing the village from as much land as possible to completely encircle and choke it from all sides and strip it of agricultural lands.

The occupation of al-Walaja, the instilling of separate yet overlapping geographic political-legal administrative and development zoning divides, contributed to a process that not only fragmented the village’s ties to its environs but further curbed its growth in residential and agricultural development. As a result, al-Walaja became a densely populated, underserved, isolated, and impoverished village, at the same time as Israeli settlements were increasingly encroaching on its lands. Thus, the physical besiegement and encroachment of settlements is accompanied by a legal regime that does not recognize the rights of the villagers even to live in their own homes, and a planning regime that prohibits all construction and development.

Very recently, Israeli plans to further expand surrounding settlements and the Separation Wall to completely encircle what is left of the village makes it clear that the Israeli plan is to swarm and besiege the village from all directions, through settlement blocs connecting up to one another.

New Settlement Plans around al-Walajah: De Facto Annexation

In addition to plans to expand Gilo and Har Homa, as well as to link them through the settlement of Givat HaMatos south of Beit Safafa, the plans include the building of the Givat Yael settlement (announced in 2004) and the Refaim Stream National Park (announced in 2013) to the north of al-Walaja. There is also a plan to build a completely new section of Har Gilo, “Har Gilo West” (announced in 2020). All of these plans entail the confiscation of al-Walaja lands.

Givat Yael settlement

The Givat Yael settlement plan was first proposed in 2004 by private investors working closely with the Israeli government, and it aims to establish about 20,000 housing units with commercial areas and recreational centers to accommodate close to 55,000 settlers.56 These settlers would occupy 60 percent of the very little territories left to al-Walaja in the area outside the municipal boundaries in the West Bank, as well as the territories of Battir and Beit Jala.57 The land on which the settlement is to be built runs along the precise borders of the built-up area of the village, locking it in and leaving it absolutely no option for natural growth.58

If built, the settlement could become the “single most populous settlement built in the occupied Palestinian territories since 1967,”59 according to the Israeli daily Maariv, and it would complete the cycle of settlements to the south that would connect Har Homa in the northeast to the recently approved Givat HaMatos, Gilo, and Har Gilo—ultimately connecting all of these to the Gush Etzion bloc.60 In doing so, Israel would complete the settlement belt that would isolate Bethlehem from Jerusalem. If built, it would constitute yet another catastrophe for the Palestinian villagers, many of whom would be displaced from their homes, which would be demolished, and from their agricultural lands, which would be razed.61

Refaim Stream National Park

The construction of the wall north of al-Walaja also made it possible for the Israel Nature and Parks Authority and the Jerusalem Development Authority to advance the Refaim Stream National Park plan. Touted as a “metropolitan park” intended to serve the public, it was approved in mid-2013 and inaugurated in early 2018 as an NIS 250-million endeavor to build a natural park over an area of about 5,700 dunums of Palestinian land confiscated from the Palestinian villages of Sharafat, Beit Safafa, and al-Walaja.62 The park would include an area for forestation, preservation, recreation, and light service facilities; an extreme sports center, horse riding center, water park, outdoor education center, and sport fields; as well as picnic areas and an arboretum.63 The National Parks and Nature Reserves website description of the park completely erases al-Walaja.

According to this plan, all of al-Walaja’s lands between the Green Line and the Separation Wall encircling the village would come under the authority of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Most of the park actually lies within the Green Line (1,850 dunums fall outside the Green Line), including atop significant parts of al-Walaja’s original pre-1948 lands. The park also connects to a chain of three large metropolitan parks being developed that would encircle the city, creating continuity between settlements inside and outside of West Jerusalem. On the one hand, the plan erases the Green Line for Israeli settlements in and around southwest Jerusalem where the park exists, while on the other, it establishes an obstructive buffer zone for Palestinians that disrupts the geographic contiguity between East Jerusalem and Bethlehem, preventing the emergence of any larger Palestinian urban area.

While it almost completely encircles the village, the park confiscates all of the farmlands of al-Walaja al-Jadida to the north of the wall. When the park was inaugurated in 2018, residents still had limited access to those lands (see The Separation Wall), which were essential, especially due to the presence there of the ‘Ayn Hinya spring. Indeed, even though the wall in that area was completed in 2010, residents were still able to go around it and access the area where the spring lay, because the checkpoint was on the Green Line, 1.5 km beyond the spring. After Israel started building the park, a plan to relocate the checkpoint was approved based on “security needs.”64 Hence, the villagers’ access to their main source of water became heavily restricted once the checkpoint moved, as the spring transformed into the park’s main attraction for the sole enjoyment of Israeli Jewish settlers.65

Objections filed by the villagers against the plan prompted Israeli planners to highlight that the project was essentially made to “protect landscape and agricultural heritage,” and they also added the aims of “encouraging traditional agriculture . . . and protecting farming terraces.” In fact, however, the plan ultimately fenced off cultivated plots of land,66 severing farmers from their lands and natural resources, including springs.67 It also disrupted the traditional agricultural stone terraces that define the Palestinian rural villages of the region. Stone terracing, an ancient farming practice among Palestinians dating back thousands of years, was preserved by Palestinians in al-Walaja and nearby Battir.

Har Gilo B and the Expansion of Bypass Road 385

While the eastern section of the wall completely blocked al-Walaja from expanding eastward, it also hindered Har Gilo, which it completely enveloped, from developing westward. As a result, in 2020, a plan to expand the Har Gilo settlement westward stipulated the creation of a whole new section of the settlement to the south of al-Walaja. This segment extension, constituting a new settlement in its own right, is often referred to as “Har Gilo West” or “Har Gilo B,” to which “Har Gilo East/A” would be connected via a bypass road. The settlement is planned on 199 dunums of land between the built-up area of al-Walaja and the bypass road to the south of the village, where 560 housing units are to be built, further reducing and suffocating al-Walaja.

To make matters even more intolerable, the plan includes an added new section of the Separation Wall: a seven-meter-high concrete wall that will run through the southeastern ridge of the village, which would complete the village’s encirclement from all sides. Thus, once completed, the wall would block off the only opening that al-Walaja residents still have to exit their village.68

The initial plan was later supplemented by another one to build a bypass road (bypass road 385) that would connect Har Gilo to Jerusalem,69 confiscating more land from the village, further reducing its area, and resulting in the demolition of more homes. The building of Har Gilo West/B is contingent on the approval of the expansion of the bypass road, against which the residents of al-Walaja have been struggling legally since 2020.70

Conclusion

For Israel, working to establish a Greater Jewish Jerusalem, the gifts that made al-Walaja one of the most important villages in Palestine, created by its geography, nature, and the centuries of care for the land, are precisely what made it a target of colonial territorial control. Since 1967, Israel has sought to create a permanent territorial linkage between the settlements it built in the East Jerusalem region to those in the south West Bank region, including the Gush Etzion bloc to the east of Bethlehem. The density of the Palestinian population right to the south of Jerusalem did not provide Israel with the possibility to cut through with a corridor. On the other hand, the spaciousness and height of al-Walaja and its close proximity to the Green Line right between the Gush Etzion settlement bloc and the illegally Israeli defined Jerusalem municipality boundaries made al-Walaja an irresistible target.

Following its first catastrophe in 1948, where the village lost most of its population and more than two thirds of its land, after the occupation of the rest the village in 1967, the village suffered continuous blows that radically uprooted their lives and livelihoods. Ever since 1967, the “facts on the ground” of settlement planning, construction, and expansion around al-Walaja reveal an underlying logic and a consistent pattern of dispossessing the village from as much land as possible to completely encircle and choke it from all sides and strip it of agricultural lands.

The occupation of al-Walaja, the instilling of separate yet overlapping geographic political-legal administrative and development zoning divides, contributed to a process that not only fragmented the village’s ties to its environs but further curbed its growth in residential and agricultural development. As a result, al-Walaja became a densely populated, underserved, isolated, and impoverished village, at the same time as Israeli settlements were increasingly encroaching on its lands. Thus, the physical besiegement and encroachment of settlements is accompanied by a legal regime that does not recognize the rights of the villagers even to live in their own homes, and a planning regime that prohibits all construction and development.

Very recently, Israeli plans to further expand surrounding settlements and the Separation Wall to completely encircle what is left of the village makes it clear that the Israeli plan is to swarm and besiege the village from all directions, through settlement blocs connecting up to one another.

Contributors

Researcher and Writer: Amir Marshi, Jerusalem Story

Editor: Nadim Bawalsa, Jerusalem Story

Research Assistant: Hassan Doostdar, Jerusalem Story

Notes

Walid Khalidi, All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992), 322.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “Al-Walajeh: A Palestinian Village Thinning in Time,” April 6, 2008.

Khalidi, All That Remains, 322–23.

Khalidi, All That Remains, 322–23.

Applied Research Institute (ARIJ)—Jerusalem, “Al Walaja Village Profile.”

PaliRoots, “Al-Badawi Tree: One of the World’s Oldest Olive Trees,” October 19, 2016.

ARIJ, “Al Walaja Village Profile,” 4.

Khalidi, All That Remains, 323.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “The Construction of a New Israeli Road East of Al Walajeh Village,” October 3, 2006; Oliver Holmes and Pablo Gutiérrez, “Seven Decades of Struggle: How One Palestinian Village’s Story Captures Pain of ‘Nakba,’” Guardian, May 13, 2018.

Khalidi, All That Remains, 322–23. See also Mikko Joronen, “Negotiating Colonial Violence: Spaces of Precarisation in Palestine,” Antipode 51, no. 3 (2019): 838–57.

UNRWA, “Thumbnail of al-Walaja” [in Arabic], July 2010.

Zochrot, “al-Walaja.”

B’Tselem, “The Village of al-Walajah: Dispossession and Home Demolitions,” April 5, 2022.

Joronen, “Negotiating Colonial Violence.”

Anne Paq, “In Photos: al-Walaja Village Faces ‘Slow Death’ as Israel takes Its Land,” Electronic Intifada, March 24, 2014.

Joronen, “Negotiating Colonial Violence.”

B’Tselem, “Refa’im Stream National Park,” September 23, 2014.

Nir Hasson, “Jerusalem Illegally Razes Four Buildings, Clearing the Way for a New Park,” Haaretz, June 10, 2020.

Joronen, “Negotiating Colonial Violence.” See also Ir Amim and Bimkom, “December 26th Supreme Court Hearing on al-Walajeh Appeal Could Lead to Largescale Destruction of Village,” December 7, 2021.

Nasser Al Qadi, “Al-Walaja: The Reality of Geopolitical Isolation,” ARIJ, February 21, 2018, 10.

UNRWA, “Thumbnail.”

UNRWA, “Thumbnail.”

UNRWA, “Al-Walaja: An Analysis under International Law,” May 2011.

ARIJ, “Al Walaja Village Profile.”

Al Qadi, “Al-Walaja.”

POICA Eye on Palestine, “Al-Walajeh.”

ARIJ, “Al Walaja Village Profile.”

Joronen, “Negotiating Colonial Violence.”

Aviv Tatarsky, “East Jerusalem Hit by Wave of Home Demolitions,” +972Magazine, May 5, 2017.

ARIJ, “Al Walaja Village Profile.”

Al Qadi, “Al-Walaja.”

UNRWA, “Thumbnail.”

UNRWA, “Al Walaja.”

Nir Hasson, “Jerusalem Planning Board Decision Paves Way for Home Demolitions in Palestinian Village,” Haaretz, February 7, 2021.

Melissa Yvonne, “Israeli Annexation: The Case of Etzion Colonial Bloc,” BADIL: Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, July 2019, 73.

Foundation for Middle East Peace, “Settlement & Annexation Report,” January 7, 2022.

Ir Amim, “Jerusalem Section of al-Walajeh under Threat of Forced Displacement,” March 10, 2021.

Hasson, “Jerusalem Board Decision.”

Ir Amim and Bimkom, “Jerusalem Section” (emphasis in original).

Ibrahim al-Araj, lawyer and resident of al-Walaja, in an interview with the author.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “The Construction of a New Israeli Road.”

The Guardian, “Palestinian Statehood: The Olive Tree of al-Walaja,” YouTube, September 19, 2011.

The original route of the wall was supposed to split the community, yet after a legal battle spearheaded by the residents in 2004, the petition to keep the community intact was accepted and the route was modified in 2005 and again in 2006.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “Al-Walajeh.”

UNRWA, “Al Walaja.”

UNRWA, “Al Walaja.”

Nir Hasson, “Renewed Work on Separation Barrier to Cut Palestinians from Their Lands,” Haaretz, April 29, 2017.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “Al-Walajeh.”

Yvonne, “Israeli Annexation,” 73.

Social TV, “WATCH: Separation Wall Engulfs Village of Al-Walaja,” +972 Magazine, February 24, 2014. See 2010 petition here: Nevo, “Al-Walajah Village Council vs. Commander in the West Bank” [in Hebrew], 2010.

POICA Eye on Jerusalem, “Israeli Expansion Activities in the Vicinity of Har Gilo Settlement,” May 13, 2008.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “The Town of al-Walaja Is Trapped by the Segregation Wall and Is under the Spot of Future Colonial Plans,” September 17, 2014.

B’Tselem, “‘The [Green] Line Is Long Gone.’”

POICA Eye on Palestine, “‘After Being Frozen for Several Years’ the Israeli Colonial Project of ‘Giv’at Yael’ Is Underway to Get Approval in the Next Few Months,” December 2, 2009.

UNRWA, “Al Walaja.”

POICA Eye on Palestine, “‘For Security & Military Purposes.’”

Hasan Abu Nimah, “Al-Walajah, a Symbol of Israeli Ethnic Cleansing,” Electronic Intifada, October 9, 2009.

POICA Eye on Palestine, “‘For Security & Military Purposes.’”

POICA Eye on Palestine, “‘After Being Frozen.’”

B’Tselem, “The Village of al-Walajah.”

POICA Eye on Palestine, “‘For Security & Military Purposes’ Expropriation of Five Dunums in al-Walajeh Village Lands Northwest of Bethlehem Governorate,” February 2, 2016.

Peace Now, “The Jerusalem Municipality Opens a Spring for Israelis Only,” February 19, 2018.

Yvonne, “Israeli Annexation,” 76.

B’Tselem, “Refa’im Stream National Park.”

B’Tselem, “The Village of al-Walajah.”

Ir Amim, “A Plan for Expanding Har Gilo Creates a Major New Threat for Al-Walaja,” October 14, 2020.

Ir Amim, “Discussion of Objections on Expansion of Al-Walaja Bypass Road Scheduled for June 21,” June 17, 2021.